Hogmanay

Hogmanay is the Scots word for the last day of the year and is synonymous with the celebration of the New Year (Gregorian calendar) in the Scottish manner. However, it is normally only the start of a celebration that lasts through the night until the morning of New Year's Day (January 1) or, in some cases, January 2—a Scottish Bank Holiday.

There are many forms of Hogmanay celebration, often involving music, dancing, drinking, and the singing of "Auld Lang Syne" at midnight. A significant feature, traditional in Scotland, is the custom of "first-footing," which begins immediately after midnight. This refers to being the first person to cross the threshold of a friend or neighbor—the "first foot"—and this person usually brings symbolic gifts such as coal, shortbread, whisky, and cake intended to bring good fortune to the household.

Etymology

The etymology of the word "Hogmanay" is obscure. The three main theories derive it either from a French, Norse, or a Goidelic (Insular Celtic) root. The word is first recorded in 1604 in the Elgin Records as hagmonay (delatit to haue been singand hagmonayis on Satirday)[1] and again in 1692 in an entry of the Scotch Presbyterian Eloquence, "It is ordinary among some plebeians in the South of Scotland to go about from door to door upon New-years Eve, crying Hagmane."[2]

Although "Hogmanay" is currently the predominant spelling and pronunciation, a number of variant spellings and pronunciations have been recorded, with the first syllable variously being /hɔg/, /hog/, /hʌg/, /hʌug/ or /haŋ/.[3]

Possible French etymologies

It may have been introduced to Middle Scots through the Auld Alliance. The most commonly cited explanation is a derivation from the Northern French dialect word hoguinané, or variants such as hoginane, hoginono and hoguinettes, those being derived from sixteenth century Middle French aguillanneuf meaning either a gift given at New Year, a children's cry for such a gift, or New Year's Eve itself.[3][4] This explanation is supported by a children's tradition, observed up to the 1960s in some parts of Scotland at least, of visiting houses in their locality on New Year's Eve and requesting and receiving small treats such as sweets or fruit.

Au gui l'an neuf (to the mistletoe for the New Year) has been suggested by some sources to indicate a druidical origin of the practice overall.[5]

Possible Goidelic etymologies

Fraser and Kelley report a Manx new-year song that begins with the line To-night is New Year's Night, Hogunnaa but did not record the full text in Manx.[6][7] Other sources parse this as hog-un-naa and give the modern Manx form as Hob dy naa.[8] Manx dictionaries though give Hop-tu-Naa, generally glossing it as "Hallowe'en,"[9] as do many of the more Manx-specific folklore collections.[10]

Another theory occasionally encountered is a derivation from the phrase thog mi an èigh/eugh I raised the cry, which, in pronunciation, resembles Hogmanay, as part of the rhymes traditionally recited at New Year[11]

Overall, Gaelic consistently refers to the New Year's Eve as Oidhche na Bliadhn(a) Ùir(e) "The Night of the New Year" and Oidhche Challainn "The Night of the Calends."[12]

Possible Norse etymologies

Some authors reject both the French and Goidelic theories, and instead suggest that the ultimate source both for the Norman French, Scots, and Goidelic variants of this word have a common Norse root.[13] It is suggested that the full forms

- Hoginanaye-Trollalay/Hogman aye, Troll a lay (with a Manx cognate Hop-tu-Naa, Trolla-laa)

- Hogmanay, Trollolay, give us of your white bread and none of your gray[14]

invoke the hill-men (Icelandic haugmenn, cf Anglo-Saxon hoghmen) or "elves" and banishes the trolls into the sea (Norse á læ "into the sea").[13]

Origins

The roots of Hogmanay perhaps reach back to the celebration of the winter solstice among the Norse,[15] as well as incorporating customs from the Gaelic celebration of Samhain. The Vikings celebrated Yule,[15] which later contributed to the Twelve Days of Christmas, or the "Daft Days" as they were sometimes called in Scotland. Christmas was not celebrated as a festival and Hogmanay was the more traditional celebration in Scotland.[16] This may have been a result of the Protestant Reformation after which Christmas was seen as "too Papist."[17]

Customs

There are many customs, both national and local, associated with Hogmanay. The most widespread national custom is the practice of first-footing, which starts immediately after midnight. This involves being the first person to cross the threshold of a friend or neighbor and often includes the giving of symbolic gifts such as salt (less common today), coal, shortbread, whisky, and black bun (a rich fruit cake) intended to bring different kinds of luck to the householder. Food and drink (as the gifts) are then given to the guests. This may go on throughout the early hours of the morning and well into the next day (although modern days see people visiting houses well into the middle of January). The first-foot is supposed to set the luck for the rest of the year. Traditionally, tall dark men are preferred as the first-foot.

Local customs

As in much of the world, the largest Scottish cities, Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Aberdeen hold all-night celebrations, as do Stirling and Inverness. The Edinburgh Hogmanay celebrations are among the largest in the world. Celebrations in Edinburgh in 1996-1997 were recognized by the Guinness Book of Records at the world's largest New Year party, with approximately 400,000 people in attendance. Numbers have since been restricted due to safety concerns.

An example of a local Hogmanay custom is the fireball swinging that takes place in Stonehaven, Aberdeenshire in north-east Scotland. This involves local people making up 'balls' of chicken wire filled with old newspaper, sticks, rags, and other dry flammable material up to a diameter of 2 feet (0.61 m), each attached to about 3 feet (0.91 m) of wire, chain, or nonflammable rope. As the Old Town House bell sounds to mark the new year, the balls are set alight and the swingers set off up the High Street from the Mercat Cross to the Cannon and back, swinging the burning balls around their heads as they go. At the end of the ceremony, any fireballs that are still burning are cast into the harbor. Many people enjoy this display, and large crowds flock to see it.[18] In recent years, additional attractions have been added to entertain the crowds as they wait for midnight, such as fire poi, a pipe band, street drumming, and a firework display after the last fireball is cast into the sea. The festivities are now streamed live over the Internet.[18]

In the east coast fishing communities and Dundee, first-footers once carried a decorated herring while in Falkland in Fife, local men marched in torchlight procession to the top of the Lomond Hills as midnight approached. Bakers in St Andrews baked special cakes for their Hogmanay celebration (known as 'Cake Day') and distributed them to local children.

In Glasgow and the central areas of Scotland, the tradition is to hold Hogmanay parties that involve singing, dancing, eating of steak pie or stew, storytelling, and drink. These usually extend into the daylight hours of January 1.

Institutions also had their own traditions. For example, amongst the Scottish regiments, officers waited on the men at special dinners while at the bells, the Old Year is piped out of barrack gates. The sentry then challenges the new escort outside the gates: 'Who goes there?' The answer is 'The New Year, all's well.'[19]

An old custom in the Highlands, which has survived to a small extent and seen some degree of revival, is to celebrate Hogmanay with the saining (Scots for 'protecting, blessing') of the household and livestock. Early on New Year's morning, householders drink and then sprinkle 'magic water' from 'a dead and living ford' around the house (a 'dead and living ford' refers to a river ford that is routinely crossed by both the living and the dead). After the sprinkling of the water in every room, on the beds and all the inhabitants, the house is sealed up tight and branches of juniper are set on fire and carried throughout the house and byre. The juniper smoke is allowed to thoroughly fumigate the buildings until it causes sneezing and coughing among the inhabitants. Then all the doors and windows are flung open to let in the cold, fresh air of the new year. The woman of the house then administers 'a restorative' from the whisky bottle, and the household sits down to its New Year breakfast.[20]

"Auld Lang Syne"

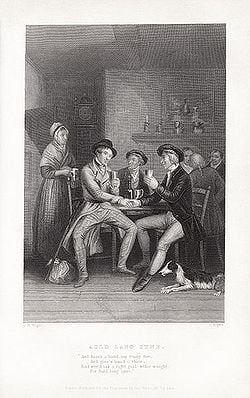

The Hogmanay custom of singing "Auld Lang Syne" has become common in many countries. "Auld Lang Syne" is a Scots poem by Robert Burns, based on traditional and other earlier sources. It is now common to sing this in a circle of linked arms that are crossed over one another as the clock strikes midnight for New Year's Day, though it is only intended that participants link arms at the beginning of the final verse, co-ordinating with the lines of the song that contain the lyrics to do so. Typically, it is only in Scotland this practice is carried out correctly.[21]

Auld Lang Syne is now sung regularly at "The Last Night of the Proms" in London by the full audience with their arms crossed over one another.

In the media

Between 1957 and 1968 a New Year's Eve television programme, called "The White Heather Club," was presented to herald in the Hogmanay celebrations. All the male dancers and Andy Stewart wore kilts, and the female dancers wore long white dresses with tartan sashes. The show was presented by Andy Stewart who always began by singing "Come in, come in, it's nice to see you...." The show always ended with Andy Stewart and the cast singing, "Haste ye Back." Following the demise of the White Heather Club, Andy Stewart continued to feature regularly in TV Hogmanay shows until his retirement.

For many years, a staple of New Year's Eve television programming in Scotland was the comedy sketch show Scotch and Wry featuring the comedian Rikki Fulton, which invariably included a hilarious monologue from him as the preternaturally gloomy Reverend I.M. Jolly.

Since 1993, the programmes that have been mainstays on BBC Scotland on Hogmanay have been Hogmanay Live and Jonathan Watson's football-themed sketch comedy show, Only an Excuse?

Presbyterian influence

The following quote (one of general disapproval of Hogmanay) is one of the first mentions of the holiday in official church records:

- It is ordinary among some plebeians in the South of Scotland to go about from door to door upon New-years Eve, crying Hagmane.[2]

Although Christmas Day held its normal religious nature in Scotland amongst its Catholic and Episcopalian communities, the Presbyterian national church, the Church of Scotland, discouraged the celebration of Christmas for nearly 400 years; it only became a public holiday in Scotland in 1958. Conversely, January 1 and 2 are public holidays and Hogmanay still is associated with as much celebration as Christmas in Scotland. Most Scots still celebrate New Year's Day with a special dinner, usually steak pie.[22]

New Year's Day

When New Year's Day falls on a Sunday, January 3 becomes an additional public holiday in Scotland; when New Year's Day falls on a Saturday, both January 3 and 4 will be public holidays in Scotland; when New Year's Day falls on a Friday, January 4 becomes an additional public holiday in Scotland.

Notes

- ↑ Aberdeen University studies (University of Michigan Library, 1900, ASIN B00300G2Z4).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 John Jamieson, Scottish Dictionary and Supplement Volume 4 (RareBooksClub.com, 2012, ISBN 978-1231097106).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Mairi Robinson (ed.), The Concise Scots Dictionary (Aberdeen University Press, 1992, ISBN 978-0080284910)

- ↑ Ronald Black (ed.), The Gaelic Otherworld (Edinburgh, Birlinn Ltd., 2012, ISBN 978-1841587332), 575: "'Hogmanay' is French in origin. In northern French dialect it was hoguinané, going back to Middle French aguillaneuf, meaning a gift given on New Year's eve or the word cried out in soliciting it."

- ↑ John Jamieson, An Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language Volume 1 (RareBooksClub.com, 2012, ISBN 978-1153807401).

- ↑ Sir James George Fraser, The Golden Bough (Dover Publications, 2002, ISBN 978-0486424927).

- ↑ Ruth Kelley, The Book of Hallowe'en (Forgotten Books, 2008, ISBN 978-1605069494)

- ↑ Folk-lore - A Quarterly Review of Myth, Tradition, Institution and Custom Vol II 1891 (Pierides Press, 2010, ISBN 978-1445521930).

- ↑ George Broderick, A Handbook of Late Spoken Manx (Max Niemeyer Verlag, 1984, ISBN 978-3484429048).

- ↑ A.W. Moore, Manx Ballads & Music (Llanerch Press, 1998, ISBN 978-1861430755).

- ↑ Origin of Hogmanay Townsville Daily Bulletin, January 5, 1940. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ↑ Colin Mark, The Gaelic-English Dictionary Routledge, 2003, ISBN 978-0415297615).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 William Harrison, Mona Miscellany (BiblioBazaar, 2009, ISBN 978-1115945622).

- ↑ Robert Chambers, Popular Rhymes of Scotland (BiblioLife, 2010, ISBN 978-1140294504).

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ben Johnson, "The History of Hogmanay" Historic UK. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Hogmanay" The Official Gateway to Scotland. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ↑ Lara Suziedelis Bogle, "Scots Mark New Year With Fiery Ancient Rites" National Geographic News, December 31, 2002. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Stonehaven Fireball Association photos and videos of festivities. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ↑ John Scotney, Scotland - Culture Smart!: The Essential Guide to Customs & Culture (Kuperard, 2009, ISBN 978-1857334920).

- ↑ F. Marian McNeill, The Silver Bough, Vol.3: A Calendar of Scottish National Festivals, Halloween to Yule (Stuart Titles Ltd, 1990, ISBN 978-0948474040).

- ↑ "Queen stays at arm's length." Lancashire Evening Telegraph, January 5, 2000. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ↑ Scottish Hogmanay Customs and Traditions at New Year About Aberdeen. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aberdeen University studies. University of Michigan Library, 1900. ASIN B00300G2Z4

- Black, Ronald (ed.). The Gaelic Otherworld. Edinburgh, Birlinn Ltd., 2012. ISBN 978-1841587332

- Broderick, George. A Handbook of Late Spoken Manx. Max Niemeyer Verlag, 1984. ISBN 978-3484429048

- Chambers, Robert. Popular Rhymes of Scotland. BiblioLife, 2010. ISBN 978-1140294504

- Fraser, Sir James George. The Golden Bough. Dover Publications, 2002. ISBN 978-0486424927

- Harrison, William. Mona Miscellany. BiblioBazaar, 2009. ISBN 978-1115945622

- Jamieson, John. Scottish Dictionary and Supplement Volume 4. RareBooksClub.com, 2012. ISBN 978-1231097106

- Jamieson, John. An Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language Volume 1. RareBooksClub.com, 2012. ISBN 978-1153807401

- Kelley, Ruth. The Book of Hallowe'en. Forgotten Books, 2008. ISBN 978-1605069494

- Mark, Colin. The Gaelic-English Dictionary Routledge, 2003. ISBN 978-0415297615

- McNeill, F. Marian. The Silver Bough, Vol.3: A Calendar of Scottish National Festivals, Halloween to Yule. Stuart Titles Ltd, 1990. ISBN 978-0948474040

- Moore, A.W. Manx Ballads & Music. Llanerch Press, 1998. ISBN 978-1861430755

- Robinson, Mairi (ed.). The Concise Scots Dictionary. Aberdeen University Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0080284910

- Scotney, John. Scotland - Culture Smart!: The Essential Guide to Customs & Culture. Kuperard, 2009. ISBN 978-1857334920

External links

All links retrieved January 11, 2018.

- Edinburgh's Hogmanay Official Web Site

- Hogmanay.net

- "The Origins, History and Traditions of Hogmanay," The British Newspaper Archive, December 31, 2012

- Hogmanay top facts

- Hogmanay Dictionary of the Scots Language

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.