Holocaust

|

The Holocaust, also known as The Shoah (Hebrew: השואה HaShoah) and the Porrajmos in Romani, is the name applied to the systematic persecution and genocide of the Jews, other minority groups, those considered enemies of the state, and also the disabled and mentally ill of Europe and European territories in North Africa during World War II by Nazi Germany and its collaborators. Early elements of the Holocaust include the Kristallnacht pogrom of November 8 and 9, 1938, and the T-4 Euthanasia Program, leading to the later use of killing squads and extermination camps in a massive and centrally organized effort to exterminate every possible member of the populations targeted by Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. Hitler's concept of a racially pure, superior race did not have room for any whom he considered to be inferior. Jews were, in his view, not only racially sub-human but traitors involved in a timeless plot to dominate the world for their own purposes.

The Jews of Europe were the main victims of the Holocaust in what the Nazis called the "Final Solution of the Jewish Question" (die "Endlösung der Judenfrage"). The commonly used figure for the number of Jewish victims is six million, though estimates by historians using, among other sources, records from the Nazi regime itself, range from five million to seven million. Also, about 220,000 Sinti and Roma were murdered in the Holocaust (some estimates are as high as 800,000), between a quarter to a half of the European population. Other groups deemed "racially inferior" or "undesirable:" Poles (5 million killed, of whom 3 million were Jewish), Serbs (estimates vary between 100,000 and 700,000 killed, mostly by Croat Ustaše), Bosniaks (estimates vary from 100,000 to 500,000), Soviet military prisoners of war and civilians on occupied territories including Russians and other East Slavs, the mentally or physically disabled, homosexuals, Jehovah's Witnesses, Communists and political dissidents, trade unionists, Freemasons, and some Catholic and Protestant clergy. Some scholars limit the Holocaust to the genocide of the Jews; some to genocide of the Jews, Roma, and disabled; and some to all groups targeted by Nazi racism.

Profound moral questions result from the Holocaust. How could such highly educated and cultured people as Austrians and Germans do such a thing? Why did ordinary people participate or allow it to happen? Where was God? Where was humanity? Why did some people and nations refuse to be involved? People inside and outside Germany knew what was happening but took very little action. More than a million Germans were implicated in the Holocaust. Even when some Jews escaped, they risked being handed back to the authorities or simply shot by civilians. Had all involved taken the moral high ground and refused to carry out orders, could even the terror-machine that was the Nazi regime have continued with its evil policy? Few doubt, except for Holocaust deniers, that pure evil stalked the killing camps. The world is still trying to make sense of the Holocaust and the lessons that can be drawn from it.

Etymology and usage of the term

The term holocaust originally derived from the Greek word holokauston, meaning a "completely (holos) burnt (kaustos)" sacrificial offering to a god. Since the late nineteenth century, "holocaust" has primarily been used to refer to disasters or catastrophes. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word was first used to describe Hitler's treatment of the Jews from as early as 1942, though it did not become a standard reference until the 1950s. By the late 1970s, however, the conventional meaning of the word became the Nazi genocide.

The biblical word Shoa (שואה), also spelled Shoah and Sho'ah, meaning "destruction" in Hebrew language, became the standard Hebrew term for the Holocaust as early as the early 1940s.[1] Shoah is preferred by many Jews and a growing number of others for a number of reasons, including the potentially theologically offensive nature of the original meaning of the word holocaust. Some refer to the Holocaust as "Auschwitz," transforming the most well known death camp into a symbol for the whole genocide.

The word "genocide" was coined during the Holocaust.

Features of the Nazi Holocaust

Efficiency

Michael Berenbaum writes that Germany became a "genocidal nation." Every arm of the country's sophisticated bureaucracy was involved in the killing process. Parish churches and the Interior Ministry supplied birth records showing who was Jewish; the Post Office delivered the deportation and de-naturalization orders; the Finance Ministry confiscated Jewish property; German firms fired Jewish workers and disenfranchised Jewish stockholders; the universities refused to admit Jews, denied degrees to those already studying, and fired Jewish academics; government transport offices arranged the trains for deportation to the camps; German pharmaceutical companies tested drugs on camp prisoners; companies bid for the contracts to build the ovens; detailed lists of victims were drawn up using the Dehomag company's punch card machines, producing meticulous records of the killings. As prisoners entered the death camps, they were made to surrender all personal property, which was carefully cataloged and tagged before being sent to Germany to be reused or recycled. Berenbaum writes that the Final Solution of the Jewish question was "in the eyes of the perpetrators … Germany's greatest achievement."[2]

Considerable effort was expended over the course of the Holocaust to find increasingly efficient means of killing more people. Early mass-murders by Nazi soldiers of thousands of Jews in Poland had caused widespread reports of discomfort and demoralization among Nazi troops. Commanders had complained to their superiors that the face-to-face killings had a severely negative psychological impact on soldiers. Committed to destroying the Jewish population, Berlin decided to pursue more mechanical methods, beginning with experiments in explosives and poisons.

The death camps had previously switched from using carbon monoxide poisoning in the Belzec, Sobibór, and Treblinka to the use of Zyklon B at Majdanek and Auschwitz.

The disposal of large numbers of bodies presented a logistical problem as well. Incineration was at first considered unfeasible until it was discovered that furnaces could be kept at a high enough temperature to be sustained by the body fat of the bodies alone. With this technicality resolved, the Nazis implemented their plan of mass-murder at its full-scale.

Alleged corporate involvement in the Holocaust has created significant controversy in recent years. Rudolf Hoess, Auschwitz camp commandant, said that the concentration camps were actually approached by various large German businesses, some of which are still in existence. Technology developed by IBM also played a role in the categorization of prisoners, through the use of index machines.

Scale

The Holocaust was geographically widespread and systematically conducted in virtually all areas of Nazi-occupied territory, where Jews and other victims were targeted in what are now 35 separate European nations and four North African nations which were then European territories, and sent to labor camps in some nations or extermination camps in others. The mass killing was at its worst in Central and Eastern Europe, which had more than 7 million Jews in 1939; about 5 million Jews were killed there, including 3 million in Poland and over 1 million in the Soviet Union. Hundreds of thousands also died in the Netherlands, France, Belgium, Yugoslavia, and Greece.

Documented evidence suggests that the Nazis planned to carry out their "final solution" in other regions if they were conquered, such as the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland.[3] Antisemitic persecution was enacted in nations such as Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia in North Africa, which were controlled by the Nazi ally, Vichy France under Marshall Petain. In Libya, under Italian control, thousands were sent to concentration camps, particularly the camp in Giado near Tripoli; Jews with foreign citizenship were sent to concentration camps in Europe. Pogroms took place in pro-German Iraq.[4]

The extermination continued in different parts of Nazi-controlled territory until the end of World War II, only completely ending when the Allies entered Germany itself and forced the Nazis to surrender in May 1945.

Cruelty

The Holocaust was carried out without any reprieve even for children or babies, and victims were often tortured before being killed. Nazis carried out deadly medical experiments on prisoners, including children. Dr. Josef Mengele, medical officer at Auschwitz and chief medical officer at Birkenau, was known as the "Angel of Death" for his medical and eugenical experiments, for example, trying to change people's eye color by injecting dye into their eyes. Aribert Heim, another doctor who worked at Mauthausen, was known as "Doctor Death."

The guards in the concentration camps carried out beatings and acts of torture on a daily basis. For example, some inmates were suspended from poles by ropes tied to their hands behind their backs so that their shoulder joints were pulled out of their sockets. Women were forced into brothels for the SS guards. Russian prisoners of war were used for experiments such as being immersed in ice water or being put into pressure chambers in which air was evacuated to see how long they would survive as a means to better protect German airmen.

Victims

The victims of the Holocaust were Jews, Serbs, Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims), Poles, Russians, Roma (also known as gypsies), some Africans, and many who could not be categorized as members of the Aryan race; Communists, Jehovah's Witnesses, some Catholic and Protestant clergy, trade unionists, and homosexuals who were classed as ideologically opposed to the Nazi state; the mentally ill and the physically disabled and psychiatric patients who were regarded as racially impure; intellectuals, political activists, common criminals, and people labeled as "enemies of the state." Freemasons were categorized as conspirators against the state and Hitler saw them as co-conspirators with the Jews, infiltrating the upper classes of society. These victims all perished alongside one another in the camps, according to the extensive documentation left behind by the Nazis themselves (written and photographed), eyewitness testimony (by survivors, perpetrators, and bystanders), and the statistical records of the various countries under occupation. Jews were categorized as Jewish according to parentage (either parent) regardless of whether they practiced Judaism, or were Christian. Christian Jews were also confined to the ghetto and compelled to wear the yellow star.

Hitler and the Jews

Anti-Semitism was common in Europe in the 1920s and 1930s (though its roots go back much further). Adolf Hitler's fanatical brand of racial anti-Semitism was laid out in his 1925 book, Mein Kampf, which, though largely ignored when it was first printed, became a bestseller in Germany once Hitler gained political power. Besides the usual elements from the Christian tradition of Jew-hatred and modern pseudo-scientific race theory it contained new aspects. For Hitler anti-Semitism was a complete explanation of the world—a worldview—that was at the center of the Nazi program, as opposed to an optional, pragmatic policy. It explained all the problems that beset Germany from its defeat in the First World War to its current social, economic, and cultural crises. Nazi anti-Semitism was also blended with the traditional German fear of Russia by claiming that Bolshevism was part of a Jewish conspiracy to take over the world as outlined in the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Hitler also believed that through inter-marriage Jews were a biological threat, corrupting and polluting the pure Aryan race. In this way Jews came to be regarded by the Nazis as vermin that ought to be exterminated.

In September 1935, two measures were announced at the annual National Socialist Party Rally in Nuremberg, becoming known as the Nuremberg Laws. Their purpose was to clarify who was Jewish and give a legal basis to discrimination against Jews. The first law, The Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor,[5][6] stripped persons not considered of German blood of their German citizenship and introduced a new distinction between “Reich citizens” and “nationals.”

In 1936, Jews were banned from all professional jobs, effectively preventing them exerting any influence in education, politics, higher education, and industry. On November 15, 1938, Jewish children were banned from going to normal schools. By April 1939, nearly all Jewish companies had either collapsed under financial pressure and declining profits, or had been forced to sell out to the Nazi-German government as part of the "Aryanization" policy inaugurated in 1937. Under such pressure between 1933 and 1939, about two-thirds of the Jewish population of Germany emigrated.

As the war started, large massacres of Jews took place, and, by December 1941, Hitler decided to "make a clean sweep."[7] In January 1942, during the Wannsee conference, several Nazi leaders discussed the details of the "Final Solution of the Jewish question" (Endlösung der Judenfrage). Dr. Josef Bühler urged Reinhard Heydrich to proceed with the Final Solution in the General Government. They began to systematically deport Jewish populations from the ghettos and all occupied territories to the seven camps designated as Vernichtungslager, or extermination camps: Auschwitz, Belzec, Chelmno, Majdanek, Maly Trostenets, Sobibór, and Treblinka.

Even as the Nazi war machine faltered in the last years of the war, precious military resources such as fuel, transport, munitions, soldiers, and industrial resources were still being heavily diverted away from the war and towards the death camps.

Death toll

By the end of the war, much of the Jewish population of Europe had been killed in the Holocaust. Lucy S. Dawidowicz used pre-war census figures to estimate that 5.934 million Jews died (see table below).[8] Additionally, smaller numbers of Jews were killed in European territories in North Africa (Vichy France Tunisia (700) and Italian Libya (650).

There were about eight to ten million Jews in the territories controlled directly or indirectly by the Nazis. The six million killed in the Holocaust thus represent 60 to 75 percent of these Jews. Of Poland's 3.3 million Jews, over 90 percent were killed. The same proportion were killed in Latvia and Lithuania, but most of Estonia's Jews were evacuated in time. Of the 750,000 Jews in Germany and Austria in 1933, only about a quarter survived. Although many German Jews emigrated before 1939, the majority of these fled to Czechoslovakia, France, or the Netherlands, from where they were later deported to their deaths. In Czechoslovakia, Greece, the Netherlands, and Yugoslavia, over 70 percent were killed. More than 50 percent were killed in Belgium, Hungary, and Romania. It is likely that a similar proportion were killed in Belarus and Ukraine, but these figures are less certain. Countries with lower proportions of deaths, but still over 20 percent, include Bulgaria, France, Italy, Luxembourg, and Norway.[9]

Denmark was able to evacuate almost all of the Jews in their country to Sweden, which was neutral during the war. Using everything from fishing boats to private yachts, the Danes whisked the Danish Jews out of harm's way. The King of Denmark had earlier set a powerful example by wearing the yellow Star of David that the Germans had decreed all Jewish Danes must wear.

| Country | Estimated Pre-War Jewish population |

Estimated killed | Percent killed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poland | 3,300,000 | 3,000,000 | 90 |

| Latvia & Lithuania | 253,000 | 228,000 | 90 |

| Germany & Austria | 240,000 | 210,000 | 90 |

| Bohemia & Moravia | 90,000 | 80,000 | 89 |

| Slovakia | 90,000 | 75,000 | 83 |

| Greece | 70,000 | 54,000 | 77 |

| Netherlands | 140,000 | 105,000 | 75 |

| Hungary | 650,000 | 450,000 | 70 |

| Byelorussian SSR | 375,000 | 245,000 | 65 |

| Ukrainian SSR | 1,500,000 | 900,000 | 60 |

| Belgium | 65,000 | 40,000 | 60 |

| Yugoslavia | 43,000 | 26,000 | 60 |

| Romania | 600,000 | 300,000 | 50 |

| Norway | 2,173 | 890 | 41 |

| France | 350,000 | 90,000 | 26 |

| Bulgaria | 64,000 | 14,000 | 22 |

| Italy | 40,000 | 8,000 | 20 |

| Luxembourg | 5,000 | 1,000 | 20 |

| Russian SFSR | 975,000 | 107,000 | 11 |

| Finland | 2,000 | 22 | 1 |

| Denmark | 8,000 | 52 | <1 |

| Total | 8,861,800 | 5,933,900 | 67 |

The exact number of people killed by the Nazi regime may never be known, but scholars, using a variety of methods of determining the death toll, have generally agreed upon common range of the number of victims.

Execution of the Holocaust

Concentration and labor camps (1940-1945)

The death camps were built by the Nazis outside Germany in occupied territory, such as in occupied Poland and Belarus (Maly Trostenets). The camps in Poland were Auschwitz, Belzec, Chelmno, Majdanek, Sobibor, and Treblinka. There was also Jasenova in Croatia, run by the Croatian Ustashe collaborators. Camps such as Dachau and Belsen that were in Germany were concentration camps, not death camps. After the invasion of Poland, the Nazis created ghettos to which Jews (and some Roma) were confined, until they were eventually shipped to death camps and killed. The Warsaw Ghetto was the largest, with 380,000 people and the Łódź Ghetto, the second largest, holding about 160,000, but ghettos were instituted in many cities. The ghettos were established throughout 1940 and 1941, and were immediately turned into immensely crowded prisons; though the Warsaw Ghetto contained 30 percent of the population of Warsaw, it occupied only about 2.4 percent of city's area, averaging 9.2 people per room. From 1940 through 1942, disease (especially typhoid fever) and starvation killed hundreds of thousands of Jews confined in the ghettos.

On July 19, 1942, Heinrich Himmler ordered the start of the deportations of Jews from the ghettos to the death camps. On July 22, 1942, the deportations from the Warsaw Ghetto inhabitants began; in the next 52 days (until September 12, 1942) about 300,000 people were transported by train to the Treblinka extermination camp from Warsaw alone. Many other ghettos were completely depopulated. Though there were armed resistance attempts in the ghettos in 1943, such as the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising as well as break-away attempts. One successful break-away was from Sobibor; 11 SS men and a number of Ukrainian guards were killed, and roughly 300 of the 600 inmates in the camp escaped, with about 50 surviving the war.

Upon arrival in these camps, prisoners were divided into two groups: those too weak for work were immediately executed in gas chambers (which were sometimes disguised as showers) and their bodies burned, while others were first used for slave labor in factories or industrial enterprises located in the camp or nearby. The Nazis also forced some prisoners to work in the collection and disposal of corpses, and to mutilate them when required. Gold teeth were extracted from the corpses, and live men and women's hair was shaved to prevent the spreading of typhus, along with shoes, stockings, and anything else of value was recycled for use in products to support the war effort, regardless of whether or not a prisoner was sentenced to death.

Many victims died in the packed railway transports before reaching the camps. Those from Poland knew exactly what awaited them. Others, from Holland and elsewhere did not and often wore their finest clothes as they journeyed to their deaths.

Death marches and liberation (1944-1945)

As the armies of the Allies closed in on the Reich at the end of 1944, the Germans decided to abandon the extermination camps, moving or destroying evidence of the atrocities they had committed there. The Nazis marched prisoners, already sick after months or years of violence and starvation, for tens of miles in the snow to train stations; then transported for days at a time without food or shelter in freight trains with open carriages; and forced to march again at the other end to the new camp. Prisoners who lagged behind or fell were shot. The largest and best known of the death marches took place in January 1945, when the Soviet army advanced on Poland. Nine days before the Soviets arrived at the death camp at Auschwitz, the Germans marched 60,000 prisoners out of the camp toward Wodzislaw, 56 km (35 mi) away, where they were put on freight trains to other camps. Around 15,000 died on the way. In total, around 100,000 Jews died during these death marches.[3]

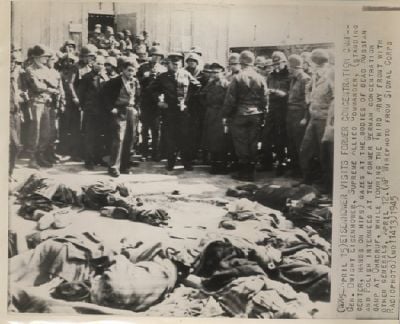

In July 1944, the first major Nazi camp, Majdanek, was discovered by the advancing Soviets, who eventually liberated Auschwitz in January 1945. In most of the camps discovered by the Soviets, the prisoners had already been transported by death marches, leaving only a few thousand prisoners alive. Concentration camps were also liberated by American and British forces, including Bergen-Belsen on April 15. Some 60,000 prisoners were discovered at the camp, but 10,000 died from disease or malnutrition within a few weeks of liberation.

Rescuers

In three cases, entire countries resisted the deportation of their Jewish population. King Christian X of Denmark of Denmark and his subjects saved the lives of most of the 7,500 Danish Jews by spiriting them to safety in Sweden via fishing boats in October 1943. Moreover, the Danish government continued to work to protect the few Danish Jews captured by the Nazis. When the Jews returned home at war's end, they found their houses and possessions waiting for them, exactly as they left them. In the second case, the Nazi-allied government of Bulgaria, led by Dobri Bozhilov, refused to deport its 50,000 Jewish citizens, saving them as well, though Bulgaria did deport Jews to concentration camps from areas in conquered Greece and Macedonia. The government of Finland refused repeated requests from Germany to deport its Finnish Jews in Germany. German requirements for the deportation of Jewish refugees from Norway and Baltic states was largely refused. In Rome, some 4,000 Italian Jews and prisoners of war avoided deportation. Many of these were hidden in safe houses and evacuated from Italy by a resistance group that was organised by an Irish priest, Monsignor Hugh O'Flaherty of the Holy Office. Once a Vatican ambassador to Egypt, O' Flaherty used his political connections to great effect in helping to secure sanctuary for dispossessed Jews.

Another example of someone who assisted Jews during the Holocaust is Portuguese diplomat Aristides de Sousa Mendes. It was in clear disrespect of the Portuguese State hierarchy that Sousa Mendes issued about 30,000 visas to Jews and other persecuted minorities from Europe. He saved an enormous number of lives, but risked his career for it. In 1941, Portuguese dictator Salazar lost political trust in Sousa Mendes and forced the diplomat to quit his career. He died in poverty in 1954.

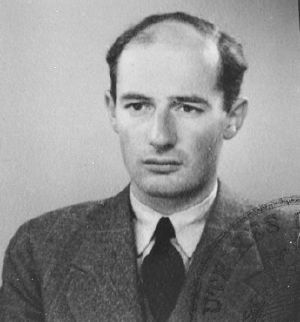

Some towns and churches also helped hide Jews and protect others from the Holocaust, such as the French town of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon which sheltered several thousand Jews. Similar individual and family acts of rescue were repeated throughout Europe, as illustrated in the famous cases of Anne Frank, often at great risk to the rescuers. In a few cases, individual diplomats and people of influence, such as Oskar Schindler or Nicholas Winton, protected large numbers of Jews. Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, the Italian Giorgio Perlasca, Chinese diplomat Ho Feng Shan and others saved tens of thousands of Jews with fake diplomatic passes. Chiune Sugihara saved several thousands of Jews by issuing them with Japanese visas against the will of his Nazi-aligned government.

There were also groups, like members of the Polish Żegota organization, that took drastic and dangerous steps to rescue Jews and other potential victims from the Nazis. Witold Pilecki, member of Armia Krajowa (the Polish Home Army), organized a resistance movement in Auschwitz from 1940, and Jan Karski tried to spread word of the Holocaust.

Since 1963, a commission headed by an Israeli Supreme Court justice has been charged with the duty of awarding such people the honorary title Righteous Among the Nations.

Perpetrators and collaborators

Who was directly involved in the killings?

A wide range of German soldiers, officials, and civilians were involved in the Holocaust, from clerks and officials in the government to units of the army, the police, and the SS. Many ministries, including those of armaments, interior, justice, railroads, and foreign affairs, had substantial roles in orchestrating the Holocaust; similarly, German physicians participated in medical experiments and the T-4 euthanasia program. And, though there was no single military unit in charge of the Holocaust, the Schutzstaffel under Himmler was the closest. From the SS came the Totenkopfverbände concentration camp guards, the Einsatzgruppen killing squads, and many of the administrative offices behind the Holocaust. The Wehrmacht, or regular German army, participated directly less than the SS in the Holocaust (though it did directly massacre Jews in Russia, Serbia, Poland, and Greece), but it supported the Einsatzgruppen, helped form the ghettos, ran prison camps, some were concentration camp guards, transported prisoners to camps, had experiments performed on prisoners, and used substantial slave labor. German police units also directly participated in the Holocaust, for example Reserve Police Battalion 101 in just over a year shot 38,000 Jews and deported 45,000 more to the extermination camps.[10]

European collaborationist countries

In addition to the direct involvement of Nazi forces, collaborationist European countries such as Austria, Italy and Vichy France, Croatia, Hungary and Romania helped the Nazis in the Holocaust. In fact Austrians had a disproportionately large role in the Holocaust. Not only were Hitler and Eichmann Austrians, Austrians made up one third of the personnel of SS extermination units, commanded four of the six main death camps and killed almost half of the six million Jewish victims. The Romanian government followed Hitler's anti-Jewish policy very closely. In October 1941, between 20,000 and 30,000 Jews were burned to death in four large warehouses that had been doused with petrol and set alight. Collaboration also took the form of either rounding up of the local Jews for deportation to the German extermination camps or a direct participation in the killings. For example, Klaus Barbie, "the Butcher of Lyon," captured and deported 44 Jewish children hidden in the village of Izieu, killed French Resistance leader Jean Moulin, and was in total responsible for the deportation of 7,500 people, 4,342 murders, and the arrest and torture of 14,311 resistance fighters was in some way attributed to his actions or commands. Police in occupied Norway rounded up 750 Jews (73 percent).

Who authorized the killings?

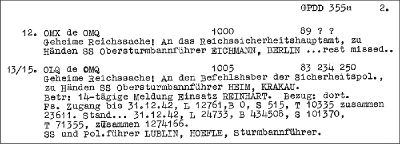

Hitler authorized the mass killing of those labeled by the Nazis as "undesirables" in the T-4 Euthanasia Program. Hitler encouraged the killings of the Jews of Eastern Europe by the Einsatzgruppen death squads in a speech in July 1941, though he almost certainly approved the mass shootings earlier. A mass of evidence suggests that sometime in the fall of 1941, Himmler and Hitler agreed in principle on the complete mass extermination of the Jews of Europe by gassing, with Hitler explicitly ordering the "annihilation of the Jews" in a speech on December 12, 1941. To make for smoother intra-governmental cooperation in the implementation of this "Final Solution" to the "Jewish Question," the Wannsee conference was held near Berlin on January 20, 1942, with the participation of fifteen senior officials, led by Reinhard Heydrich and Adolf Eichmann, the records of which provide the best evidence of the central planning of the Holocaust. Just five weeks later on February 22, Hitler was recorded saying "We shall regain our health only by eliminating the Jew" to his closest associates.

Arguments that no documentation links Hitler to "the Holocaust" ignore the records of his speeches kept by Nazi leaders such as Joseph Goebbels and rely on artificially limiting the Holocaust to exclude what we do have documentation on, such as the T-4 Euthanasia Program and the Kristallnacht pogrom (November 9–10, 1938, when synagogues were set on fire in Austria and Germany, thousands of Jews were killed and 30,000 taken to the concentration camps).

Who knew about the killings?

Some claim that the full extent of what was happening in German-controlled areas was not known until after the war. However, numerous rumors and eyewitness accounts from escapees and others gave some indication that Jews were being killed in large numbers. Since the early years of the war the Polish government-in-exile published documents and organized meetings to spread word of the fate of the Jews. By early 1941, the British had received information via an intercepted Chilean memo that Jews were being targeted, and by late 1941 they had intercepted information about a number of large massacres of Jews conducted by German police. In the summer of 1942, a Jewish labor organization (the Bund) got word to London that 700,000 Polish Jews had already died, and the BBC took the story seriously, though the United States State Department did not.[11] By the end of 1942, however, the evidence of the Holocaust had become clear and on December 17, 1942, the Allies issued a statement that the Jews were being transported to Poland and killed.

The U.S. State Department was aware of the use and the location of the gas chambers of extermination camps, but refused pleas to bomb them out of operation. This was because it was believed that the speedy and total defeat of Hitler was the best way to help the Jews and attacks on death camps would be a distraction. On the other hand anti-Semitism in the United States between 1938 and 1945 was so strong that very few Jewish refugees were admitted.[12] On May 12, 1943, Polish government-in-exile and Bund leader Szmul Zygielbojm committed suicide in London to protest the inaction of the world with regard to the Holocaust, stating in part in his suicide letter:

I cannot continue to live and to be silent while the remnants of Polish Jewry, whose representative I am, are being killed. My comrades in the Warsaw ghetto fell with arms in their hands in the last heroic battle. I was not permitted to fall like them, together with them, but I belong with them, to their mass grave.

By my death, I wish to give expression to my most profound protest against the inaction in which the world watches and permits the destruction of the Jewish people.

Debate continues on how much average Germans knew about the Holocaust. Recent historical work suggests that the majority of Germans knew that Jews were being indiscriminately killed and persecuted, even if they did not know of the specifics of the death camps.

Historical and philosophical interpretations

The Holocaust and the historical phenomenon of Nazism, which has since became the dark symbol of the twentieth century's crimes, has became the subject of numerous historical, psychological, sociological, literary and philosophical studies. All types of scholars tried to give an answer to what appeared as the most irrational act of the Western World, which, until at least World War I, had been so sure of its eminent superiority on other civilizations. Many different people have tried to give explanation for what many deemed unexplainable by its horror. Genocide has too often been the result when one national group tries to control a state.

One important philosophical question, addressed as soon as 1933 by Wilhelm Reich in Mass Psychology of Fascism, was the mystery of the obedience of the German people to such an "insane" operation. Hannah Arendt, in her 1963 report on Adolf Eichmann, made of this last one the symbol of dull obedience to authority, in what was seen at first as a scandalous book, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963), which has since became a classic of political philosophy. Thus, Arendt opposed herself to the first, immediate, explanation, which accused the Nazis of "cruelty" and of "sadism." Later, the historians' debate concerning functionalism and intentionalism also demonstrated that the question couldn't be simplified to a question of cruelty. Many people who participated in the Holocaust were normal people, according to Arendt. Perhaps they were beguiled by Hitler's charisma. Hitler delivered on the economy and in restoring German pride; many simply did not want to believe what was happening. Others theorize about the psychology of "obedience," of obeying orders.

Hannah Arendt and some authors, such as Sven Lindqvist or Olivier LeCour Grandmaison, also point to a relative continuity between the crimes committed against "primitive" people during colonialism and the Holocaust. They most notably argue that many techniques which the Nazi would perfect had been used in other continents such as concentration camps which were developed during the Boer Wars if not before. This thesis was met with fierce opposition by some groups, who argued that nothing could be compared to the Holocaust, not even other genocides: Although the Herero genocide (1904-07) and the Armenian genocide (1915-17) are commonly considered as the first genocides in history, many argued that the Holocaust had taken proportions that even these crimes against humanity hadn't achieved. Subsequent genocides, though equally a stain on the human story, such as those in Bosnia and Rwanda, are also of a much smaller scale and in comparison were carried out by primitive means of execution, such as using clubs and machetes.

Many have pointed out that the Holocaust was the culmination of nearly 2000 years of traditional Christian Anti-Semitism—the teaching of contempt of Judaism (known as Adversus Iudeaos) which has its roots in the New Testament. This teaching included the popular accusation that the Jews had committed "deicide" in killing Jesus, that the Jews uttered a curse on themselves for so doing—"His blood be on us and on our children" (Matthew 27:25). Also, Jews constitutionally place money ahead of God, as exemplified by Judas Iscariot's (his name "Judas" became a synonym for "Jew") selling of the Lord for thirty pieces of silver. Further misconceptions included the accusation of ritual murder, in which Jews were said to kill a Christian infant to extract blood for the Passover. European Christian art frequently depicted anti-semitic images, such as the Judensau (German for "Jews' sow"), a derogatory and dehumanizing image of Jews in obscene contact with a large female pig, an animal unclean to Jew, which appeared in the Middle Ages in carvings on church or cathedral walls and in woodcuts, and was revived by the Nazis.

This popular stereotyping and demonizing of Jews meant that there was a widespread implicit if not explicit feeling that what was happening to the Jews was, if not right, at least understandable. There were many layers to this Antisemitism. One was also a strong feeling of envy and resentment to the widespread financial and cultural success of Jews. Another was the popular association of Jews with Communism. Furthermore, the science of eugenics developed in the nineteenth century by associates of Charles Darwin claimed that some races were more evolved than others. All these ideas fed into the Nazi ideas of Aryan racial superiority and made it easier for Nazis to believe that what they were doing was right and justified.

Why did people allow the killing?

Obedience

Stanley Milgram was one of a number of post-war psychologists and sociologists who tried to address why people obeyed immoral orders in the Holocaust. Milgram's findings demonstrated that reasonable people, when instructed by a person in a position of authority, obeyed commands entailing what they believed to be the death or suffering of others. These results were confirmed in other experiments as well, such as the Stanford prison experiment. In his book Mass Psychology of Fascism (1933), Wilhelm Reich also tried to explain this obedience. The work became known as the foundation of freudo-marxism. Nobel Nobel prize winner Elias Canetti also addressed the problem of mass obedience in Masse und Macht (1960—"Crowds and Power"), developing an original theory of the consequences of commandments orders both in the obedient person and in the commander, who may well become a "despotic paranoiac."

Functionalism versus intentionalism

A major issue in contemporary Holocaust studies is the question of functionalism versus intentionalism. The terms were coined in a 1981 article by the British Marxist historian Timothy Mason to describe two schools of thought about the origins of the Holocaust. Intentionalists hold that the Holocaust was the result of a long-term masterplan on the part of Hitler and that he was the driving force behind the Holocaust. Functionalists hold that Hitler was anti-Semitic, but that he did not have a master plan for genocide. Functionalists see the Holocaust as coming from below in the ranks of the German bureaucracy with little or no involvement on the part of Hitler. Functionalists stress that the Nazi anti-Semitic policy was constantly evolving in ever more radical directions and the end product was the Holocaust.

Intentionalists like Lucy Dawidowicz argue that the Holocaust was planned by Hitler from the very beginning of his political career, at very least from 1919 on, if not earlier. The decision for genocide has been traced back as early as November 11, 1918. More recent intentionalist historians like Eberhard Jäckel continue to emphasize the relative. Intentionalist historians such as the American Arno J. Mayer claim Hitler only ordered the Holocaust in December 1941.

Functionalists like hold that the Holocaust was started in 1941-1942 as a result of the failure of the Nazi deportation policy and the impending military losses in Russia. They claim that what some see as extermination fantasies outlined in Hitler's Mein Kampf and other Nazi literature were mere propaganda and did not constitute concrete plans. In Mein Kampf, Hitler repeatedly states his inexorable hatred of the Jewish people, but nowhere does he proclaim his intention to exterminate the Jewish people. This, though, can easily be read into the text.

In particular, Functionalists have noted that in German documents from 1939 to 1941, the term "Final Solution to the Jewish Question" was clearly meant to be a "territorial solution," that is the entire Jewish population was to be expelled somewhere far from Germany and not allowed to come back. At first, the SS planned to create a gigantic "Jewish Reservation" in the Lublin, Poland area, but the so-called "Lublin Plan" was vetoed by Hans Frank, the Governor-General of Poland who refused to allow the SS to ship any more Jews to the Lublin area after November 1939. The reason why Frank vetoed the "Lublin Plan" was not due to any humane motives, but rather because he was opposed to the SS "dumping" Jews into the Government-General. In 1940, the SS and the German Foreign Office had the so-called "Madagascar Plan" to deport the entire Jewish population of Europe to a "reservation" on Madagascar. The "Madagascar Plan" was canceled because Germany could not defeat the United Kingdom and until the British blockade was broken, the "Madagascar Plan" could not be put into effect. Finally, Functionalist historians have made much of a memorandum written by Himmler in May 1940, explicitly rejecting extermination of the entire Jewish people as "un-German" and going on to recommend to Hitler the "Madagascar Plan" as the preferred "territorial solution" to the "Jewish Question." Not until July 1941 did the term "Final Solution to the Jewish Question" come to mean extermination.

Controversially, sociologist Daniel Goldhagen argues that ordinary Germans were knowing and willing participants in the Holocaust, which he claims had its roots in a deep eliminationist German anti-Semitism. Most other historians have disagreed with Goldhagen's thesis, arguing that while anti-Semitism undeniably existed in Germany, Goldhagen's idea of a uniquely German "eliminationist" anti-Semitism is untenable, and that the extermination was unknown to many and had to be enforced by the dictatorial Nazi apparatus.

Religious hatred and racism

The German Nazis considered it their duty to overcome natural compassion and to execute orders for what they believed were higher ideals. Much research has been conducted to explain how ordinary people could have participated in such heinous crimes, but there is no doubt that, as in some religious conflicts in the past, some people poisoned with a racial and religious ideology of hatred committed the crimes with sadistic pleasure. Crowd psychology has attempted to explain such heinous acts. Gustave Le Bon's The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1895) was a major influence on Mein Kampf, in particular relating to the propaganda techniques which Hitler described. Sadistic acts were perhaps most notable in the case of genocide of the Croation Nazi collaborators, the whose enthusiasm and sadism in their killings of the Serbs appalled Germans, Italians, and even German SS officers, who even acted to restrain the Ustaše. However, concentration camp literature, such as by Primo Levi or Robert Antelme, described numerous individual sadistic acts, including acts carried out by Kapos (Trustees; Jews given privileges to act as spies for the German prison authorities).

Holocaust denial

Holocaust denial, also called Holocaust revisionism, is the belief that the Holocaust did not occur, or, more specifically: that far fewer than around six million Jews were killed by the Nazis (numbers below one million, most often around 30,000 are typically cited); that there never was a centrally-planned Nazi attempt to exterminate the Jews; and/or that there were not mass killings at the extermination camps. Those who hold this position often further claim that Jews and/or Zionists know that the Holocaust never occurred, yet that they are engaged in a massive conspiracy to maintain the illusion of a Holocaust to further their political agenda. As the Holocaust is generally considered by historians to be one of the best documented events in recent history, these views are not accepted as credible by scholars, with organizations such as the American Historical Association, the largest society of historians in the United States, stating that Holocaust denial is "at best, a form of academic fraud."[13]

Holocaust deniers almost always prefer to be called Holocaust revisionists. Most scholars contend that the latter term is misleading. Historical revisionism, in the original sense of the word, is a well-accepted and mainstream part of the study of history; it is the reexamination of accepted history, with an eye towards updating it with newly discovered, more accurate, and/or less biased information, or viewing known information from a new perspective. In contrast, negationists typically willfully misuse or ignore historical records in order to attempt to prove their conclusions, as Gordon McFee writes:

"Revisionists" depart from the conclusion that the Holocaust did not occur and work backwards through the facts to adapt them to that preordained conclusion. Put another way, they reverse the proper methodology […], thus turning the proper historical method of investigation and analysis on its head.[14]

Public Opinion Quarterly summarized that: "No reputable historian questions the reality of the Holocaust, and those promoting Holocaust denial are overwhelmingly anti-Semites and/or neo-Nazis." Holocaust denial has also become popular in recent years among radical Muslims: In late 2005, Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad denounced the Holocaust of European Jewry as a "myth."[15] Public espousal of Holocaust denial is a crime in ten European countries (including France, Poland, Austria, Switzerland, Belgium, Romania, and Germany), while the Nizkor Project attempts to counter it on the Internet.

Aftermath

Displaced persons and the state of Israel

The Holocaust and its aftermath left millions of refugees, including many Jews who had lost most or all of their family members and possessions, and often faced persistent anti-Semitism in their home countries. The original plan of the Allies was to repatriate these "Displaced Persons" to their country of origin, but many refused to return, or were unable to as their homes or communities had been destroyed. As a result, more than 250,000 languished in DP camps for years after the war ended. While Zionism had been prominent before the Holocaust, afterward it became almost universally accepted among Jews. Many Zionists, pointing to the fact that Jewish refugees from Germany and Nazi-occupied lands had been turned away by other countries, argued that if a Jewish state had existed at the time, the Holocaust could not have occurred on the scale it did. With the rise of Zionism, Palestine became the destination of choice for Jewish refugees. However as local Arabs opposed the immigration, the United Kingdom placed restrictions on the number of Jewish refugees allowed into Palestine. Former Jewish partisans in Europe, along with the Haganah in Palestine, organized a massive effort to smuggle Jews into Palestine, called Berihah, which eventually transported 250,000 Jews (both DPs and those who hid during the war) to the Mandate. By 1952, the Displaced Persons camps were closed, with over 80,000 Jewish DPs in the United States, about 136,000 in Israel, and another 20,000 in other nations, including Canada and South Africa.

Legal proceedings against Nazis

The juridical notion of crimes against humanity was invented following the Holocaust. There were a number of legal efforts established to bring Nazis and their collaborators to justice. Some of the higher ranking Nazi officials were tried as part of the Nuremberg Trials, presided over by an Allied court; the first international tribunal of its kind. In total, 5,025 Nazi criminals were convicted between 1945-1949 in the American, British and French zones of Germany. Other trials were conducted in the countries in which the defendants were citizens—in West Germany and Austria, many Nazis were let off with light sentences, with the claim of "following orders" ruled a mitigating circumstance, and many returned to society soon afterward. An ongoing effort to pursue Nazis and collaborators resulted, famously, in the capture of Holocaust organizer Adolf Eichmann in Argentina (an operation led by Rafi Eitan) and to his subsequent trial in Israel in 1961. Simon Wiesenthal became one of the most famous Nazi hunters.

Some former Nazis, however, escaped any charges. Thus, Reinhard Gehlen a former intelligence officer of the Wehrmacht, set up the a network which helped many ex-Nazis to escape to Spain (under Franco), Latin America or in the Middle East. Gehlen later worked for the CIA, and in 1956 created the Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND), the German intelligence agency, which he directed until 1968. Klaus Barbie, known as "the Butcher of Lyon" for his role at the head of the Gestapo, was protected from 1945 to 1955 by the MI-5 (British security service) and the CIA, before fleeing to South America. Barbie was finally arrested in 1983 and sentenced to life imprisonment for crimes against humanity in 1987. In October 2005, Aribert Heim (aka "Doctor Death") was found to be living for twenty years in Spain, protected by Gehlen's network. Paul Schäfer, who had founded Colonia Dignidad in Chile, was arrested in 2005 on child sex abuses charges. Furthermore, some "enlightened" Nazis were pardoned and permitted to become members of the Christian Democrats in Germany. These included Kurt Georg Kiesinger, who became Germany's Chancellor for a period in the 1960s, Hans Filbinger, who became Minister President of Baden-Württemberg, and Kurt Waldheim, who became Secretary-General of the United Nations and President of Austria. Many Jews have been critical of the trials that have been conducted, suggesting that often the judges had Nazi leanings. One Sobibor survivor, recounting her experiences as a witness, responded to the question, "was justice done" by saying:

Not all … They just took advantage of us witnesses. We didn't keep records in Sobibor. It was out word against theirs. They just tried to confuse the witnesses. I had the feeling that they would have loved to put me on trial … If I met a younger judge, you could expect a little compassion… If the judge had been a student or judge before the war, I knew he was one of them.[16]

Until recently, Germany refused to allow access to massive Holocaust-related archives located in Bad Arolsen due to, among other factors, privacy concerns. However, in May 2006, a 20-year effort by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum led to the announcement that 30-50 million pages would be made accessible to historians and survivors.

Legal action against genocide

The Holocaust also galvanized the international community to take action against future genocide, including the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide in 1948. While international human rights law moved forward quickly in the wake of the Holocaust, international criminal law has been slower to advance; after the Nuremberg trials and the Japanese war crime trials it was over forty years until the next such international criminal procedures, in 1993 in Yugoslavia. In 2002, the International Criminal Court was set up.

Impact on culture

Holocaust theology

On account of the magnitude of the Holocaust, Christian and Jewish thinkers have re-examined the classical theological views on God's goodness and actions in the world. A field known as Holocaust Theology has evolved. Jewish responses have fallen into two categories. The first is represented by figures such as Richard Rubenstein, Emil Fackenheim, and Elie Wiesel. They could not accept the traditional understanding that when Israel had flourished, she was being blessed by God but when misfortune, such as the Exile, came, this was punishment for sin. Rubenstein spoke into an almost silent Jewish world on the topic of the Holocaust when he asked, "where was God when the Jews were being murdered?"[17] He offered an atheistic response in his "death of God" theology stating that the Shoah had made it impossible to continue believing in a covenential God of history. Many simply wanted to survive so that, as it is often put, Hitler does not enjoy a posthumous victory. Rubenstein suggested that post-Holocaust belief in God, in a divine plan or in meaning is intellectually dishonest. Rather, one must assert one's own value in life. Although some survivors became atheists, this theological response has not proved to be popular.

Emil Fackenheim (1916-2003) (who escaped to Britain) suggests that God must be revealing something paradigmatic or epoch-making through the Holocaust, which we must discern. Some Jews link this with the creation of the State of Israel, where Jews are able to defend themselves. Drawing in the ancient Jewish concept of mending or repairing the world (tikkun olam). Fackenheim says it is the Jews' duty to ensure that evil does not prevail, and that a new commandment, that Hitler does not posthumously win, is upheld.[18]

Nobel Prize winner and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel suggests that most people pose the wrong question, which should be "where was humanity during the Holocaust, not where was God?" "Where," he says, "was man in all this, and culture, how did it reach this nadir?"[19]

Rabbi Hugo Gryn also said the real question is, "Where was man in Auschwitz?" Although he admits that people often ask, "Where was God?" Gryn’s answer to this latter question was, “I believe that God was there Himself—violated and blasphemed.” While in Auschwitz on Yom Kippur, he fasted and hid away and tried to remember the prayers that he had learned as a child at the synagogue. He asked God for forgiveness. Eventually, he says, “I dissolved in crying. I must have sobbed for hours… Then I seemed to be granted a curious inner peace… I believe God was also crying… I found God.”[20] But it was not the God of his childhood who, as a child, he had expected miraculously to rescue the Jews. Rabbi Hugo Gryn found God in the camps, but a God who was crying. Other thinkers, both Christian and Jewish, in their reflection on the Shoah have spoken of a Suffering God.

A second response has been to view the Shoah in the same way as were other periods of persecution and oppression. Scholars such as Jacob Neusner, Eliezer Berkovits and Eugene Borowitz have taken this view. Some ultra-orthodox put the blame for the Shoah on the unfaithfulness of Jews who had abandoned traditional Judaism in favor of other ideologies such as Socialism, Zionism, or various non-Orthodox Jewish movements, but most deny that anything Jews have done could merit such severe punishment.

Harold Kushner argued that God is not omnipotent and can not be blamed for humanity's exercise of free will or for massive evil in the world.[21] Eliezer Berkovits (1908-1992) revived the Kabbalistic notion that sometimes God inexplicably withdraws from the world to argue that during the Holocaust God was "hidden."[22]

In a rare view that has not been adopted by any sizable element of the Jewish or Christian community, Ignaz Maybaum (1897-1976) has proposed that the Holocaust is the ultimate form of vicarious atonement. The Jewish people become in fact the "suffering servant" of Isaiah. The Jewish people suffer for the sins of the world. In his view: "In Auschwitz Jews suffered vicarious atonement for the sins of mankind." Many Jews see this as too Christian a view of suffering; some Christians respond to the question, where was God when the Jews were murdered by saying that he was there with them, also suffering, in the gas chambers.

Art and literature

German philosopher Theodor Adorno famously commented that "writing poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric," and the Holocaust has indeed had a profound impact on art and literature, for both Jews and non-Jews. Some of the more famous works are by Holocaust survivors or victims, such as Elie Wiesel, Primo Levi, and Anne Frank, but there is a substantial body of post-holocaust literature and art in many languages; for example the poetry of Paul Celan who explicitly sought to meet Adorno's challenge.

The Holocaust has also been the subject of many films, including Oscar winners Schindler's List and Life Is Beautiful. There has been extensive efforts to document survivors' stories, in which a number of agencies have been involved.

Holocaust Memorial Days

In a unanimous vote, the United Nations General Assembly voted on November 1, 2005, to designate January 27 as the "International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust." January 27, 1945 is the day that the former Nazi concentration and extermination camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau was liberated. Even before the UN vote, January 27 was already observed as Holocaust Memorial Day in the United Kingdom since 2001, as well as other countries, including Sweden, Italy, Germany, Finland, Denmark and Estonia. Israel observes Yom HaShoah, the "Day of Remembrance of the Holocaust," on the 27th day of the Hebrew month of Nisan, which generally falls in April. This memorial day is also commonly observed by Jews outside of Israel.

Notes

- ↑ History: The Holocaust: Timeline and History of the Holocaust - What is the Holocaust? Yad Vashem. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ↑ Michael Berenbaum, The World Must Know (United States Holocaust Museum, 2006, ISBN 978-0801883583), 104.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 I.C.B. Dear and M.R.D. Foot, The Oxford Companion to World War II (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 019280670X).

- ↑ North Africa and the Middle East Yad Vashem. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ↑ Nuremberg Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor, September 15, 1935 Yad Vashem. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ↑ The Nuremberg Laws: The Reich Citizenship Law (September 15, 1935) Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ↑ Lorraine Boissoneault, The First Moments of Hitler’s Final Solution Smithsonian Magazine, December 12, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Lucy S. Dawidowicz, The War against the Jews, 1933–1945 (New York, NY: Bantam Books, 1986, ISBN 0553343025), 403.

- ↑ The Fate of the Jews Across Europe Yad Vashem. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ↑ Donald L. Niewyk and Francis Nicosia, The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2000, ISBN 0231112009), 83-87.

- ↑ Richard Breitman, What Chilean Diplomats Learned about the Holocaust U.S. National Archives. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ↑ Paul Johnson, A History of the Jews (New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 1988, ISBN 978-0060915339), 503.

- ↑ Donald L. Niewyk, The Holocaust: Problems and Perspectives of Interpretation (Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath & Co., 1992, ISBN 0669272914).

- ↑ Gordon McFee, Why 'Revisionism' isn't May 15, 1999. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ↑ Tom W. Smith, The Holocaust Denial Controversy Public Opinion Quarterly 59(2) (Summer 1995): 269-295. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ↑ Richard Rashke, Escape from Sobibor (New York: Avon, 1982, ISBN 0380753944), 309.

- ↑ Richard L. Rubenstein, After Auschwitz: Radical Theology and Contemporary Judaism (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merril, 1966, ISBN 0801842859).

- ↑ Emil Fackenheim, To Mend the World: Foundations of Future Jewish Thought (New York: Schocken Books, 1994, ISBN 025332114X).

- ↑ Elie Wiesel, A Jew Today (New York: Vintage, 1978, ISBN 0394740572).

- ↑ Hugo Gryn, Chasing Shadows (London: Viking, 2000, ISBN 0670887935).

- ↑ Harold Kushner, When Bad Things Happen to Good People (Boston, MA: G.K. Hall, 1982, ISBN 0816134650).

- ↑ Eliezer Berkowitz, Faith after the Holocaust (KTAV Publishing House, 1973, ISBN 978-0870681936).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Berenbaum, Michael. The World Must Know. United States Holocaust Museum, 2006. ISBN 978-0801883583

- Berkowitz, Eliezer. Faith after the Holocaust. KTAV Publishing House, 1973. ISBN 978-0870681936

- Dawidowicz, Lucy S. The War Against the Jews, 1933–1945. New York, NY: Bantam Books, 1986. ISBN 0553343025

- Dear, I.C.B., and M.R.D. Foot. The Oxford Companion to World War II. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 019280670X

- Fackenheim, Emil. To Mend the World: Foundations of Future Jewish Thought. New York, NY: Schocken Books, 1994. ISBN 025332114X

- Gryn, Hugo. Chasing Shadows. London: Viking, 2000. ISBN 0670887935

- Johnson, Paul. A History of the Jews. New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 1988. ISBN 978-0060915339

- Kushner, Harold. When Bad Things Happen to Good People. Boston, MA: G. K Hall, 1982. ISBN 0816134650

- Niewyk, Donald L. The Holocaust: Problems and Perspectives of Interpretation. Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath & Co., 1992. ISBN 0669272914

- Niewyk, Donald L., and Francis Nicosia. The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2000. ISBN 0231112009

- Rashke, Richard. Escape from Sobibor. New York, NY: Avon, 1982. ISBN 0380753944

- Rubenstein, Richard L. After Auschwitz: Radical Theology and Contemporary Judaism. Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merril, 1966. ISBN 0801842859

- Wiesel, Elie. A Jew Today. New York, NY: Vintage, 1978. ISBN 0394740572

External links

All links retrieved October 11, 2023.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Yad Vashem - The World Holocaust Remembrance Center

- The Holocaust: Crimes, Heroes and Villains

- The Holocaust Wing Jewish Virtual Library

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.