Holy Spirit

| Part of a series of articles on Christianity | ||||||

| ||||||

|

Foundations Bible Christian theology History and traditions

Topics in Christianity Important figures | ||||||

|

Christianity Portal | ||||||

The Holy Spirit refers to the third person of the Trinity in Christianity. In Judaism the Holy Spirit refers to the life-giving breath or spirit of God, as the Hebrew word for "spirit" in the Hebrew Bible is ruach (breath). The Greek word for "spirit" in the New Testament is pneuma (air, wind). The New Testament has a wealth of profound references to the spiritual work of the Holy Spirit among believers and in the Church.

The Trinitarian doctrine of the Holy Spirit as a distinct "person" which shares, from the beginning of existence, the same substance with the Father and the Son was proposed by Tertullian (c.160-c.225) and established through the Councils of Nicea (325) and Constantinople (381). Especially the Cappadocian Fathers were instrumental in helping to establish it. Later a technical disagreement arose about whether the Holy Spirit "proceeds" only from the Father or from both the Father and the Son, eventually occasioning the Great Schism between Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism in 1054.

While the work of the Holy Spirit is widely known, we are hard-pressed to arrive at a precise definition. This may be because, compared with the Father and the Son, there is a lack of concrete imagery of the Holy Spirit. One issue is its gender. The Hebrew word for "spirit," ruach, is of feminine gender, while the Greek word pneuma is neuter. Despite the Church's official doctrine that the Holy Spirit is masculine, individuals and groups throughout the history of Christianity, including luminaries like St. Jerome (c.342-420) and Martin Luther (1483-1546), have repeatedly proposed that the Holy Spirit is feminine. In rabbinic Judaism the Holy Spirit is equated with the Shekhinah, the mother aspect of God. In light of the biblical notion of the androgynous image of God who created male and female in his image (Gen. 1:27), it has been suggested that a feminine Holy Spirit would be the appropriate counterpart to the male figure of the Son, who is manifest in Jesus Christ. The work of the Holy Spirit as comforter, intercessor and source of inspiration could be represented in the ministrations of Mary and other holy women of God.

The Holy Spirit in Judaism

The Holy Spirit in Judaism is not distinguished from God as a "person," but is seen more as an aspect, essence, or attribute of God. The word for spirit in Hebrew is ruach, and it is closely related to the concept of breath. In the Book of Genesis, God's spirit hovered over the form of lifeless matter, thereby making the Creation possible (Gen. 1:2). God blew the breath of life into Adam (Gen. 2:7). The Book of Job affirms that "The Spirit of God hath made me, and the breath of the Almighty hath given me life" (Job 33:4;). God is the God of the spirits of all flesh (Num. 16:22). The breath of animals also is derived from Him (Gen. 6:17; Eccl. 3:19-21; Isa. 42:5).

Thus, all creatures live only through the spirit given by God. However, the terms "spirit of God" and "spirit of the Lord" are not limited to the sense of God as a life-giving spirit. He "pours out" His spirit upon those whom He has chosen to execute His will. This spirit imbues them with spiritual power or wisdom, making them capable of heroic speech and action (Gen. 41:38; Ex. 31:3; Num. 24:2; Judges 3:10; II Sam. 23:2). The spirit of God rests upon man (Isa. 6:2); it surrounds him like a garment (Judges 6:34); it falls upon him and holds him like a hand (Ezek. 6:5, 37:1). It may also be taken away from the chosen one and transferred to some one else (Num. 6:17). It may enter into man and speak with his voice (II Sam. 23:2; Ezek. ii. 2). The prophet sees and hears by means of the spirit (Num. I Sam. 10:6; II Sam. 23:2, etc). The prophet Joel predicted (2: 28-29) that in the Day of the Lord "I will pour out my Spirit upon all flesh; and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, your old men shall dream dreams, your young men shall see visions: And also upon the servants and upon the handmaids in those days will I pour out my Spirit."

What the Bible calls "Spirit of Yahweh (the Lord)" and "Spirit of Elohim (God)" is called in the Talmud and Midrash "Holy Spirit" ("Ruach ha-Kodesh"). The specific expression "Holy Spirit" also occurs in Ps. 52:11 and in Isa. 63:10-11.

In rabbinical literature, the Shekhinah is often referred to instead of the Holy Spirit. It is said of the Shekhinah, as of the Holy Spirit, that it rests upon a person, inspires the righteous, and dwells among the congregation as the Queen of the Sabbath. Like ruach, Shekhinah is a feminine noun, and its function among the congregation and with regard to certain especially holy rabbis, is specifically bride-like.

The Holy Spirit in the New Testament

Many passages in the New Testament speak of the Holy Spirit. The word for spirit in New Testament Greek is pneuma, which means air or wind. Unlike the Hebrew ruach, it is a neuter noun, and the masculine pronoun is used for it.

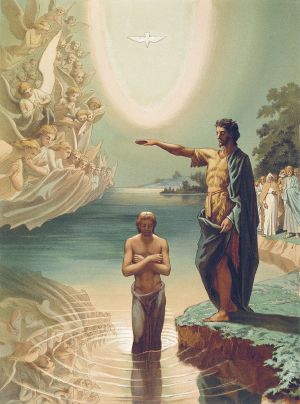

The Holy Spirit made a first appearance, coming upon Jesus in the form of a dove at the beginning of his ministry when he was baptized by John the Baptist in the Jordan River (Matthew 3:13-17, Mark 1:9-11, Luke 3:21-22, John 1:31-33). But the real appearance of the Holy Spirit is said to have been recognized in the words of Jesus, speaking to his disciples sometime near his death (John 14:15-18). Jesus reportedly described the Holy Spirit as the promised "Advocate" (John 14:26, New American Bible). In the Great Commission, he instructs his disciples to baptize all men in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. Although the language used to describe Jesus' receiving the Spirit in John's Gospel is parallel to the accounts in the other three Gospels, John relates this with the aim of showing that Jesus is specially in possession of the Spirit for the purpose of granting the Spirit to his followers, uniting them with himself, and in himself also uniting them with the Father. After his resurrection, Jesus is said to have told his disciples that they would be "baptized with the Holy Spirit," and would receive power from this event (Acts 1:4-8), a promise that was fulfilled in the events recounted in the second chapter of the Book of Acts. On the first Pentecost, Jesus' disciples were gathered in Jerusalem when a mighty wind was heard and tongues of fire appeared over their heads. A multilingual crowd heard the disciples speaking, and each of them heard them speaking in his or her native language.

The Spirit is said to dwell inside every true Christian, each person's body being God's temple (1 Corinthians 3:16). The Holy Spirit is depicted as a "Counselor" or "Helper" (Paraclete), guiding people in the way of the truth. The Spirit's action in one's life is believed to produce positive results, known as the Fruit of the Spirit. A list of gifts of the Spirit includes the charismatic gifts of prophecy, tongues, healing, and knowledge.

Third Person of the Trinity

The New Testament talks about the triadic formula for baptism—"in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost"—in the Great Commission (Matthew 28:19). This formula can also be seen in second-century Christian writings such as the Didache, Ignatius of Antioch (c.35-107) and Tertullian (c.160-c.225) and third-century writers such as Hippolytus (c.170-c.236), Cyprian (d.258), and Gregory Thaumaturgus (c.213-c.270). It apparently became a fixed expression.

However, the exact nature of the Holy Spirit and its relationship to the other components of the Godhead already became a matter of significant debate within the Christian community by the second century. Many criticized the early triadic formula of teaching "three gods" instead of one. In order to safeguard monotheism, a theological movement called "Monarchianism" emphasized the oneness of the triad. One form of this movement, Modalistic Monarchianism, expressed the operation of the triad as three modes of God's being and activity. Another form of the movement, Dynamistic Monarchianism, saw God the Father as supreme, with the Son and the Holy Spirit as creatures rather than being co-eternal with the Father. The influential Church Father Tertullian responded to this situation by maintaining that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are neither merely three modes of one and the same God nor three entirely separate things, but rather "distinct" from one another. Tertullian used the expression of "three persons" (tres personae). However, the Latin word persona in those days meant legal ownership or a character, not necessarily a distinct self-conscious being. Thus three distinct "persons" were still of "one substance" (una substantia). It was in this context that Tertullian also used the word Trinity (trinitas). The terms that Tertullian coined considerably influenced the later Councils of Nicea (325) and of Constantinople (381).

In the fourth century, the aftermath of the Arian controversy led to numerous debates about the Holy Spirit. Eunomians, Semi-Arians, Acacians, for example, all admitted the triple personality of the Godhead but denied the doctrine of "consubstantiality" (sharing one substance). The Council of Constantinople established "consubstantiality" of the Holy Spirit with the Father and Son. It also declared that the Holy Spirit was not "created," but that it "proceeded" from the Father. Thus, the Holy Spirit was now firmly established as the Third Person of the Trinity, really distinct from the Father and the Son, but also existing with them from the beginning and sharing the same divine substance.

Procession of the Holy Spirit

The Holy Spirit "proceeds from the Father" (John 16:25). The term "procession" regarding the Holy Spirit was made popular by the Cappadocian Fathers. They even made a distinction between the eternal procession of the Holy Spirit within the Godhead, on the one hand, and the "economic" procession of the same for the providence of salvation in the world, on the other.

The procession of the Holy Spirit from the Father is similar to the generation of the Son from the Father because neither procession nor generation means creation. Both procession and generation are immanent operations within the Godhead, although they can also occur in the "economic" sense as well. Procession and generation are also similar because generation is a kind of procession. However, both are different from each other because the procession of the Holy Spirit is usually understood to be the activity of the divine will, while the generation of the Son is rather the activity of the divine intelligence.

There is a controversial technical difference between the views of Eastern and Western Christianity regarding the involvement of the Son in the procession of the Holy Spirit. This is the difference of single vs. double procession. Eastern Orthodoxy teaches that the Holy Spirit proceeds only from the Father, i.e., from the Father through the Son. By contrast, Western Churches, including the Roman Catholic Church and most Protestant denominations, teach that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son. Hence the Roman Catholic version of the Nicene Creed reads: "We believe in the Holy Spirit … who proceeds from the Father and the Son." Historically, this addition of "and the Son" (filioque) was made in Spain in the sixth century, and it was strongly objected to by the Orthodox Church, which eventually declared it a heresy, leading ultimately to the Great Schism between Catholicism and Orthodox in 1054.

Additional Interpretations

Roman Catholicism

The Catechism of the Catholic Church states the following in the first paragraph dealing with the Apostles Creed's article I believe in the Holy Spirit:

"No one comprehends the thoughts of God except the Spirit of God" (152). Now God's Spirit, who reveals God, makes known to us Christ, his Word, his living Utterance, but the Spirit does not speak of himself. The Spirit who "has spoken through the prophets" makes us hear the Father's Word, but we do not hear the Spirit himself. We know him only in the movement by which he reveals the Word to us and disposes us to welcome him in faith. The Spirit of truth who "unveils" Christ to us "will not speak on his own." Such properly divine self-effacement explains why "the world cannot receive [him], because it neither sees him nor knows him," while those who believe in Christ know the Spirit because he dwells with them. (687)

As regards the Holy Spirit's relationship with the Church, the Catechism states:

- The mission of Christ and the Holy Spirit is brought to completion in the Church, which is the Body of Christ and the Temple of the Holy Spirit. (737)

- Thus the Church's mission is not an addition to that of Christ and the Holy Spirit, but is its sacrament: in her whole being and in all her members, the Church is sent to announce, bear witness, make present, and spread the mystery of the communion of the Holy Trinity. (738)

- Because the Holy Spirit is the anointing of Christ, it is Christ who, as the head of the Body, pours out the Spirit among his members to nourish, heal, and organize them in their mutual functions, to give them life, send them to bear witness, and associate them to his self-offering to the Father and to his intercession for the whole world. Through the Church's sacraments, Christ communicates his Holy and sanctifying Spirit to the members of his Body. (739)

Orthodoxy

Orthodox doctrine regarding the Holy Trinity is summarized in the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed. Eastern Catholics and Oriental Orthodox also coincide with Eastern Orthodox usage and teachings on the matter. The Holy Spirit plays a central role in Orthodox worship: the liturgy usually begins with a prayer to the Holy Spirit and invocations made prior to sacraments are addressed to the Spirit. In particular, the epiclesis prayer which blesses the eucharistic bread and wine is meant to invite the Holy Spirit to descend during the Holy Communion.

Protestantism

Most Protestant churches are basically trinitarian in nature, affirming the belief that the Holy Spirit is a distinct "person" sharing the same substance with God the Father and God the Son, but some of them place unique emphasis on the Holy Spirit or hold particular views about the Holy Spirit that set them somewhat apart from the norm.

For example, Pentecostalism derives its name from the event of Pentecost, the coming of the Holy Spirit when Jesus' disciples were gathered in Jerusalem. Pentecostalism also believes that, once received, the Holy Spirit is God working through the recipient to perform the gifts of the Spirit. These gifts are portrayed in 1 Corinthians chapter 12. The Pentecostal movement places special emphasis on the work of the Holy Spirit, especially the gift of speaking in tongues. Many Pentecostals hold that the "baptism of the Holy Spirit" is a distinct form of the Christian regeneration, separate from the "born-again" experience of conversion or water baptism. Many believe that Holy Spirit baptism is a necessary element in salvation.

Dispensationalism teaches that the current time is the age of the Holy Spirit, or church age, a teaching that can be found in Medieval writers such as Joachim of Fiore and St. Bonaventure. Late nineteenth-century dispensationalists understood history as a process of seven dispensations, the last dispensation of which would be the thousand-year reign of Christ.

The expression Third Wave was coined by Christian theologian C. Peter Wagner around 1980 to describe what followers believe to be the recent historical work of the Holy Spirit. It is part of a larger movement known as the Neocharismatic movement. The Third Wave involves those Christians who have allegedly received Pentecostal-like experiences, however Third Wavers claim no association with either the Pentecostal or Charismatic movements.

Nontrinitarian Views

In the belief of many nontrinitarian denominations—Christadelphians, Unitarians, The Latter-day Saints and Jehovah's Witnesses, for instance—the Holy Spirit is viewed in ways that do not conform to the traditional formula of the Councils of Nicea and Constantinople. For Christadelphians, Unitarians, and Jehovah's Witnesses, the Holy Spirit is not a distinct person of the Trinity but rather merely God's spiritual power. This is similar to the Jewish view. Some Christadelphians even believe that the Holy Spirit is in fact an angel sent by God.[1]

Jehovah's Witnesses teach that[2] the Holy Spirit is not a person or a divine member of the Godhead. At his baptism Jesus received God's spirit (Matthew 3:16), but according to Witnesses it conflicts with the idea that the Son was always one with the Holy Spirit. Also, regarding Jesus' statement: "But of that day and [that] hour knoweth no man, no, not the angels which are in heaven, neither the Son, but the Father" (Mark 13:32), Witnesses note that the Holy Spirit is conspicuously missing there, just as it is missing from Stephen's vision in (Acts 7:55, 56), where he sees only the Son and God in heaven. The Holy Spirit is thus the spiritual power of God, not a distinct person.

The nontrinitarianism of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is a little different. It teaches that the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are separate from one another, although they are "one God" in the sense that they are one "in purpose." The Holy Spirit exists as a distinct and separate being from the Father and the Son, having a body of spirit with no flesh and bones, whereas the Father and the Son are said to be resurrected individuals having immortalized bodies of flesh and bone.

Femininity of the Holy Spirit

To begin with, the Hebrew word for "spirit" in the Hebrew Bible is ruach, meaning breath, and its gender is feminine. Also, in Greek, Logos is the masculine term for Word, and its feminine counterpart is Sophia, meaning Wisdom; so, if the Son is the incarnation of the Logos, the Holy Spirit could be considered to to have something to do with the Sophia, thus being feminine. For these and other reasons, numerous Christian individuals and groups have considered that the gender of the Holy Spirit is feminine, contrary to the official Church view of the Holy Spirit as masculine. Some early Christians apparently took this view. For example, the Gospel of Thomas (v. 101) speaks of the Holy Spirit as Jesus' "true mother," and the Gospel of the Hebrews refers to "my mother, the Holy Spirit." Excerpts of the Gospel of the Hebrew on this point survived in the writings of Origen (c.185-c.254) and Saint Jerome (c.342-420) who apparently accepted it.[3]

Syriac documents, which remain in today's Syrian Orthodox Church, refer to the Holy Spirit as feminine because of the feminine gender of the original Aramaic word "spirit." Coptic Christianity also saw the Holy Spirit as the Mother, while regarding the two persons of the Trinity as the Father and Son. So did Zinzendorf (1700-1760), the founder of Moravianism. Even Martin Luther, the driving force of the Protestant Reformation, was reportedly "not ashamed of speaking of the Holy Spirit in feminine terms," but his feminine terminology in German was translated into English masculine terms.[4]

More recently, Catholic scholars such as Willi Moll, Franz Mayr, and Lena Boff have also characterized the Holy Spirit as feminine. According to Moll, for example, when the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son, the Holy Spirit is passive and the other two persons active; so, the Holy Spirit is feminine, while the other two are masculine.[5] Numerous Catholic artworks have made a special connection between the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary, implying a feminine aspect to the Holy Spirit.

Interestingly, the "Messianic Jewish" Christian movement B'nai Yashua Synagogues Worldwide[6] headed by Rabbi Moshe Koniuchowsky, also holds to the feminine view of the Holy Spirit. Based in part on the rabbinical teaching of the femininity of the Shekhinah, there are several other Messianic Jewish-Christian groups with similar teachings. Some examples include Joy In the World, The Torah and Testimony Revealed, and the Union of Nazarene Jewish Congregations/Synagogues, which also counts as canonical the fragmentary Gospel of the Hebrews which has the unique feature of referring to the Holy Spirit as Jesus' "Mother."

There are some scholars associated with "mainstream" Protestant denominations, who while not necessarily indicative of the denominations themselves, have written works explaining a feminine understanding of the third member of the Godhead. For example, R. P. Nettlehorst, professor at the Quartz Hill School of Theology (associated with the Southern Baptist Convention) has written on the subject.[7][8][9] Evan Randolph, associated with the Episcopal Church, has likewise written on the subject.[10][11]

Depiction in Art

The Holy Spirit is often depicted as a dove, based on the account of the Holy Spirit descending on Jesus in the form of a dove when he was baptized in the Jordan. In many paintings of the Annunciation, the Holy Spirit is shown in the form of a dove, coming down toward Mary on beams of light, representing the Seven Gifts, as the Angel Gabriel's announces Christ's coming to Mary. A dove may also be seen at the ear of Saint Gregory the Great - as recorded by his secretary - or other Church Father authors, dictating their works to them.

The dove also parallels the one that brought the olive branch to Noah after the deluge (also a symbol of peace), and Rabbinic traditions that doves above the water signify the presence of God.

The Book of Acts describes the Holy Spirit descending on the apostles at Pentecost in the form of a wind and tongues of fire resting over the apostles' heads. Based on the imagery in that account, the Holy Spirit is sometimes symbolized by a flame of fire.

Constructive Assessment

The doctrine of the Holy Spirit is rather enigmatic because, as compared with the Father and the Son, of whom we can have concrete human images, the Holy Spirit lacks concrete imagery except non-human images such as dove and wind. Furthermore, whereas the Son can refer to Jesus in history, the Holy Spirit normally cannot refer to any agent in the realm of creation. These can perhaps explain the diversity of views on the Holy Spirit. But, amidst the diversity of views, whether they are trinitarian or nontrinitarian, or whether they are Eastern or Western, there seems to be one trend which has incessantly popped up in spite of the Church's official rejection of it. It is to understand the Holy Spirit in feminine terms. It cannot be entirely rejected if Genesis 1:27 is meant to say that the image of God is both male and female. Also, if it is true that men and women were created in this androgynous image of God, we can surmise that just as the Son is manifested by a man—Jesus, the feminine Holy Spirit is linked to, or can be represented by, a woman. Spiritually, then, the Holy Spirit would represent the Bride of Christ. Perhaps this can help to address the enigmatic nature of the doctrine of the Holy Spirit.

See also

- God

- Christ

- Jesus

- Trinity

- Virgin Mary

- Agape

- Pneumatology

- Revelation

- Athanasian Creed

- A Course in Miracles

Notes

- ↑ Angel www.aletheiacollege.net. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- ↑ Holy Spirit. www.watchtower.org. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- ↑ [1] Retrieved January 9, 2008.

- ↑ [2] Retrieved Janauary 9, 2008.

- ↑ Willi Moll. The Christian Image of Women. (Notre Dome: Fides, 1967).

- ↑ Messianic Jews/ yourarmstoisrael.org.

- ↑ R.P. Nettelhorst, "More Than Just a Controversy: All About The Holy Spirit". [3].www.theology.edu.Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- ↑ [4]."Pneumatology: Doctrine of the Holy Spirit" www.theology.edu.Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- ↑ "The Holy Spirit in the Old Testament." [5].www.theology.edu. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- ↑ Church Fathers believed Holy Spirit was Feminine[6] Quotes. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- ↑ Evan Randolph[7] Sources for research on the Holy Spirit. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Burgess, Stanley M. The Holy Spirit: Eastern Christian Traditions. Hendrickson Publishers, 1989. ISBN 9780913573815

- Küng, Hans, and Jürgen Moltmann. Conflicts About the Holy Spirit. Seabury Press, 1980. ISBN 978-0816420353

- Schandorff, Esther Dech. The Doctrine of the Holy Spirit: A Bibliography Showing Its Chronological Development. ATLA bibliography series, no. 28. Scarecrow Press, 1995. ISBN 9780810825239

- Schaupp, Joan P. Woman: Image of the Holy Spirit. International Scholars Publications, 1996. ISBN 9781573091152

- Stanton, Graham, et al. The Holy Spirit and Christian Origins: Essays in Honor of James D.G. Dunn. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co, 2004. ISBN 9780802828224

- Stephens, Bruce M. The Holy Spirit in American Protestant Thought, 1750-1850. Studies in American religion, v. 59. E. Mellen Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0773491939

- Wright, Christopher J. H. Knowing the Holy Spirit Through the Old Testament. IVP Academic, 2006. ISBN 9780830825912

External links

All links retrieved January 13, 2018.

- The Work Of the Holy Spirit. www.spirithome.com.

- How To Live By The Power Of The Holy Spirit Protestant-Christian. www.new-testament-christian.com.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.