Horus

Horus is one of the most archaic gods of the classical Egyptian pantheon, one whose longevity is at least partially attributable to the syncretic incorporation and accommodation of various lesser deities and cults. In the most developed forms of the myth corpus, he was characterized as both the child of Isis and Osiris, and the all-powerful ruler of the universe.

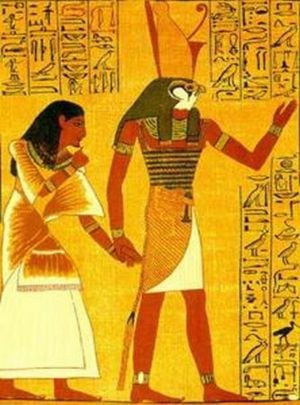

In the mythic cosmos, Horus was most notably seen as a sky god, which accounts for his iconographic representation as a falcon-headed man. He was also characterized as the ruler of the living (both humans and gods), a title that he wrested from Set after the latter's murder of Osiris. Due to his identification with temporal leadership, Horus came to be seen as the god who bestowed divinity upon the pharaoh.

In the original Egyptian, his name was Heru or Har, though he is far better known in the West as "Horus" (the Hellenized version of his moniker).

Horus in an Egyptian Context

| ḥr "Horus" in hieroglyphs | ||

|

As an Egyptian deity, Horus belonged to a complex religious, mythological and cosmological belief system developed in the Nile river basin from earliest prehistory to 525 B.C.E.[1] Indeed, it was during this relatively late period in Egyptian cultural development, a time when they first felt their beliefs threatened by foreigners, that many of their myths, legends and religious beliefs were first recorded.[2] The cults within this framework, whose beliefs comprise the myths we have before us, were generally fairly localized phenomena, with different deities having the place of honor in different communities.[3] Despite this apparently unlimited diversity, however, the gods (unlike those in many other pantheons) were relatively ill-defined. As Frankfort notes, “the Egyptian gods are imperfect as individuals. If we compare two of them … we find, not two personages, but two sets of functions and emblems. … The hymns and prayers addressed to these gods differ only in the epithets and attributes used. There is no hint that the hymns were addressed to individuals differing in character.”[4] One reason for this was the undeniable fact that the Egyptian gods were seen as utterly immanental—they represented (and were continuous with) particular, discrete elements of the natural world.[5] Thus, those who did develop characters and mythologies were generally quite portable, as they could retain their discrete forms without interfering with the various cults already in practice elsewhere. Also, this flexibility was what permitted the development of multipartite cults (i.e. the cult of Amun-Re, which unified the domains of Amun and Re), as the spheres of influence of these various deities were often complimentary.[6]

The worldview engendered by ancient Egyptian religion was uniquely appropriate to (and defined by) the geographical and calendrical realities of its believer’s lives. Unlike the beliefs of the Hebrews, Mesopotamians and others within their cultural sphere, the Egyptians viewed both history and cosmology as being well ordered, cyclical and dependable. As a result, all changes were interpreted as either inconsequential deviations from the cosmic plan or cyclical transformations required by it.[7] The major result of this perspective, in terms of the religious imagination, was to reduce the relevance of the present, as the entirety of history (when conceived of cyclically) was ultimately defined during the creation of the cosmos. The only other aporia in such an understanding is death, which seems to present a radical break with continuity. To maintain the integrity of this worldview, an intricate system of practices and beliefs (including the extensive mythic geographies of the afterlife, texts providing moral guidance (for this life and the next) and rituals designed to facilitate the transportation into the afterlife) was developed, whose primary purpose was to emphasize the unending continuation of existence.[8] Given these two cultural foci, it is understandable that the tales recorded within this mythological corpus tended to be either creation accounts or depictions of the world of the dead, with a particular focus on the relationship between the gods and their human constituents.

Origin of name

The name of the falcon god is recorded in Egyptian hieroglyphs as ḥr.w and is reconstructed to have been pronounced *Ḥāru, which means "Falcon," "high-flying one," or "Distant One." By Coptic times, the name became Hōr. It was later Hellenized into Greek as "Ὡρος" (Hōros). The original name also survives in later Egyptian names such as Har-Si-Ese, literally "Horus, son of Isis."[9]

Mythology

Sky god

From earliest Egyptian prehistory, the "concretist" understanding of the cosmos (described above) led to a complex identification between deities, their animal representations/incarnations, and elements of the natural order. It was in this context that Horus, the best-known of the falcon-headed deities, emerged.[10] As a sky god, he "was imagined as a celestial falcon whose right eye was the sun and left eye the moon. The speckled feathers of his breast were probably stars and his wings the sky—with their downsweep producing the winds."[11] The popularity of Horus led to his eventual eclipsing of various other falcon deities, including Nekheny (literally "falcon"), the patron of Nekhen (the city of the hawk), and Khenty-Kety, the patron of Athribis.[12] One common symbol associated with Horus in his celestial incarnation was the djed pillar, which was understood to represent the "pillar holding the sky above the earth."[13]

These celestial connotations were explored in greater detail in the myths, rituals, and iconographic depictions that characterized Horus as a solar deity.

Sun god

Since Horus was seen as a sky god, it was natural that he also became conflated with the firmament's most prominent inhabitants: the sun and moon. In particular, the two celestial orbs came to be associated with the god's eyes, and their cyclical movements were explained as resulting from his traversal in falcon form. Thus, he became known as Heru-merty - "Horus of two eyes."[14]

Given the association between Horus and the celestial spheres, it was only a matter of time before an etiological myth arose to explain why one orb was brighter than the other. This explanatory fable, known as the Contestings of Horus and Set, answered this age-old question while simultaneously presenting a metaphor for the conquest of Lower Egypt by Upper Egypt in about 3000 B.C.E. In this tale, it was said that Set, the patron of Lower Egypt, and Horus, the patron of Upper Egypt, had engaged in a ferocious conflict for unilateral control over the entire country. In the struggle, Set lost a testicle, explaining why the desert, which Set represented, was agriculturally infertile. Horus' left eye had also been gouged out, which explained why the moon, which it represented, was so weak compared to the sun.[15] It was also said that during a new-moon, Horus had become blinded and was titled Mekhenty-er-irty (mḫnty r ỉr.ty "He who has no eyes"), while when the moon became visible again, he was re-titled Khenty-irty (ḫnty r ỉr.ty "He who has eyes"). While blind, it was considered that Horus was quite dangerous, sometimes attacking his friends after mistaking them for enemies.[14]

In the end, the other gods intervened, siding with Horus and ceding him the fertile territories throughout the land (and leaving Set the sere wastelands as his prize). As Horus was the ultimate victor he became known as Harsiesis, Heru-ur or Har-Wer (ḥr.w wr "Horus the Great"), but more usually translated as "Horus the Elder." This monarchial form of the deity was tremendously important for the legitimation of the dynastic succession (as discussed below).[16]

Ultimately, Horus also became identified with Ra as Ra-Herakhty rˁ-ˁḫr-3iḫṯ, literally "Ra, who is Horus of the two horizons." However, this identification proved to be awkward, for it made Ra into the son of Hathor, which diminished his austere status as a creator deity. Even worse, the unification of Ra and Horus was complicated by the fact that the latter was typically understood as the son of the former (meaning that Ra was literally being characterized as his own father). In spite of these mythico-theological problems, temples to Ra-Herakhty were relative prominent for many centuries—a fact that stands as a testament to the influence and popularity of the falcon god.[17] This was, of course, less of an issue in those construals of the pantheon that did not feature Ra as a creator god, such as the version of the Ogdoad creation myth used by the Thoth cult, where Ra-Herakhty emerged from an egg laid by the ibis-god.

God of the Pharaohs

As Horus was the son of Osiris, and god of the sky, he became closely associated with the Pharaoh of Upper Egypt (where Horus was worshipped), and became their patron. The association with the Pharaoh brought with it the idea that he was the son of Isis, in her original form, who was regarded as a deification of the Queen. Further, his domination of Set (and subsequent unification of the land) provided an exemplary model for human political leaders, who viewed themselves as part of the god's dynastic lineage:

- Horus was directly linked with the kingship of Egypt in both his falconiform aspect and as son of Isis. From the earliest Dynastic Period the king's name was written in the rectangular device known as the serekh which depicted the Horus falcon perched on a stylized palace enclosure and which seems to indicate the king as mediator between the heavenly and earthly realms, if not the god manifest within the palace of the king himself. To this 'Horus name' of the monarch other titles were later added, including the 'Golden Horus' name in which a divine falcon is depicted upon the hieroglyphic sign for gold, though the significance of this title is less clear. The kingship imagery is found in the famous statue of Khafre seated with the Horus falcon at the back of his head and in other similar examples. As the son of Isis and Osiris Horus was also the mythical heir to the kingship of Egypt, and many stories surrounding his struggle to gain and hold the kingship from the from the usurper Seth detail this aspect of the god's role.[18]

Conqueror of Set

By the nineteenth dynasty (ca. 1290-1890 B.C.E.), the previous enmity between Set and Horus, during which Horus had ripped off one of Set's testicles, was revitalized through a separate tale. According to Papyrus Chester-Beatty I, Set was considered to have been homosexual and is depicted trying to prove his dominance by seducing Horus and then having intercourse with him. However, Horus places his hand between his thighs and catches Set's semen, then subsequently throws it in the river, so that he may not be said to have been inseminated by Set. Horus then deliberately spreads his own semen on some lettuce, which was Set's favorite food. After Set has eaten the lettuce, they go to the gods to try to settle the argument over the rule of Egypt. The gods first listen to Set's claim of dominance over Horus, and call his semen forth, but it answers from the river, invalidating his claim. Then, the gods listen to Horus' claim of having dominated Set, and call his semen forth, and it answers from inside Set.[19] In consequence, Horus is declared the ruler of Egypt.

This myth, along with others, could be seen as an explanation of how the two kingdoms of Egypt (Upper and Lower) came to be united. Horus was seen as the God of Upper Egypt, and Set as the God of Lower Egypt. In this myth, the respective Upper and Lower deities have a fight, through which Horus comes to be seen as the victor. Further, a physical part of Horus (representing Upper Egypt) enters into Set (Lower Egypt), offering further explanation for the dominance of the Upper Egyptians over the Lower Egyptians.

Brother of Isis

When Ra assimilated Atum into Atum-Ra, Horus became considered part of what had been the Ennead. Since Atum had had no wife, having produced his children by masturbating, Hathor was easily inserted into these accounts as the parent of Atum's previously motherless progeny. Conversely, Horus did not fit in so easily, since if he was identified as the son of Hathor and Atum-Ra in the Ennead, he would then be the brother of the primordial air and moisture, and the uncle of the sky and earth, between which there was initially nothing, which was not very consistent with him being the sun. Instead, he was made the brother of Osiris, Isis, Set, and Nephthys, as this was the only plausible level at which he could meaningfully rule over the sun and the Pharaoh's kingdom. It was in this form that he was worshipped at Behdet as Har-Behedti (also abbreviated Bebti).[20]

Since Horus had become more and more identified with the sun since his unification with Ra, his identification as the moon suffered. As a result, it was suddenly possible for other moon gods to emerge without complicating the system of belief too much. Consequently, Chons became the moon god. Thoth, who had also been the moon god, became much more associated with secondary mythological aspects of the moon, such as wisdom, healing, and peace making. When the cult of Thoth arose in power, Thoth was retroactively inserted into the earlier myths, making Thoth the one whose magic caused Set and Horus' semen to respond (as in the tale of the contestings of Set and Horus, for example.

Mystery religion

- See also: Osiris , Mystery Religion , and Serapis

Given Horus' (at times indirect) association with life, death and rebirth, he played an important role in the development of Egyptian/Hellenistic mystery religion. Though this role is more often ascribed to Osiris, the falcon god also played an important part, especially since the two gods were somewhat interchangeable in the classical religious imagination. Certain historical factors made such an identification rather natural, as both gods were described as husbands of Isis (in certain construals of the pantheon), not to mention the fact that their magisteria were seen to be utterly discrete (with Horus ruling over the living and Osiris over the dead). Since Horus had been conceived after his father's untimely demise, he also represented the ultimate triumph of the pantheon over the forces of chaos and death. In fact, after a few centuries, it came to be said that Horus was the resurrected form of Osiris.

The combination of this now rather esoteric mythology (which also included various adaptations to the classical understandings of Horus, Isis, and Osiris) with the philosophy of Plato, which was becoming popular on the Mediterranean shores, led to the tale becoming the basis of a mystery religion. Many who encountered the faith thought it so profound that they sought to create their own interpretations, modeled upon the Egyptian original but utilizing their own pantheons. This led to the creation of what was effectively one religion, which was, in many places, adjusted to superficially reflect the local mythology although it substantially adjusted them. The religion is known to modern scholars as that of Osiris-Dionysus.[21]

The Birth of Horus in Cultic Life

Given its mythical particulars, Horus' nativity sequence calls out for comparison with other popular theogonies. Before exploring these correspondences, however, it is first necessary to outline the mature version of the god's birth narrative. In particular, Isis came to be identified with Neith, the mother of Ra, who existed as a personification of the primal waters of creation. Since the goddess became pregnant without direct male intervention, Neith (and later Isis) were considered to have given birth whilst remaining virginal. As the various religious groups gained and lost power in Egypt, the legend varied accordingly, such that, when the cult of Thoth sought to involve themselves in the story, it was said that Thoth's wisdom led to his foretelling of the god's birth. Likewise, since the later legends had other gods in existence at Ra's birth, it was said that they acknowledged Ra's authority by praising him at his birth. These factors were later transposed into the tales of Horus' birth. Iconographically, one of the most prominent sculptural images used by this cult was Neith/Isis bearing (or suckling) the infant Horus.

Later, the tale evolved to include the god Kneph, who represented the breath of life. This was partly in recognition of a small cult of Kneph, but was more generally a simple acknowledgment of the importance of this divine breath in the generation of Horus, the most holy of gods. As a creator, Kneph became identified as the more dominant creator deity Amun, and when Amun became Amun-Ra, so to did Kneph gained Hathor (/Isis) as a wife. In a later interpretation, Plutarch suggested that Kneph was understood by the Egyptians in the same way as the Greeks understood pneuma, meaning spirit, which meant that Neith became pregnant by the actions of a holy spirit.

Many of the features in this account are undeniably similar to the nativity of Jesus, such as the perpetual virginity of the mother, the lack of a corporeal father, the annunciation by a celestial figure, and the particular iconographic representation of mother and child. While these similarities could simply have arisen by chance, it seems more likely that there was some cultural overlap in the development of the Christian nativity narrative.[22]

Notes

- ↑ This particular "cut-off" date has been chosen because it corresponds to the Persian conquest of the kingdom, which marks the end of its existence as a discrete and (relatively) circumscribed cultural sphere. Indeed, as this period also saw an influx of immigrants from Greece, it was also at this point that the Hellenization of Egyptian religion began. While some scholars suggest that even when "these beliefs became remodeled by contact with Greece, in essentials they remained what they had always been" (Erman, 203), it still seems reasonable to address these traditions, as far as is possible, within their own cultural milieu.

- ↑ The numerous inscriptions, stelae and papyri that resulted from this sudden stress on historical posterity provide much of the evidence used by modern archeologists and Egyptologists to approach the ancient Egyptian tradition (Pinch, 31-32).

- ↑ These local groupings often contained a particular number of deities and were often constructed around the incontestably primary character of a creator god (Meeks and Meeks-Favard, 34-37).

- ↑ Frankfort, 25-26.

- ↑ Zivie-Coche, 40-41; Frankfort, 23, 28-29.

- ↑ Frankfort, 20-21.

- ↑ Assmann, 73-80; Zivie-Coche, 65-67; Breasted argues that one source of this cyclical timeline was the dependable yearly fluctuations of the Nile (8, 22-24).

- ↑ Frankfort, 117-124; Zivie-Coche, 154-166.

- ↑ Pinch, 143; Budge (1969), Vol. I, 466; Wilkinson, 200. See also: Online Etymology Dictionary, 2000-Names.com. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ↑ Frankfort, 10, 28.

- ↑ Wilkinson, 200.

- ↑ Pinch, 143. See also the article on ancient Egyptian gods at the Encyclopedia of the Orient and a discussion of Nekheny at ancient-worlds.net. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ↑ Pinch, 128.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Budge (1969), Vol I, 469-470.

- ↑ Pinch, 192; Wilkinson, 197-198; Budge (1969), Vol. II, 245-246. See also: Pyramid Texts 1463e: "[Ra] was born before the eye of Horus was plucked out; before the testicles of Set were torn away."

- ↑ Budge (1969), Vol I, 469-470; Pinch, 143; Wilkinson, 201-202.

- ↑ Pinch, 184.

- ↑ Wilkinson, 201. See also: Budge (1969), Vol. I, 473-486, for a lengthy overview of cult and mythology of the Great Horus.

- ↑ R. B. Parkinson, "'Homosexual' Desire and Middle Kingdom Literature," The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 81 (1995), 57-76, 65-66; Theology WebSite: The 80 Years of Contention Between Horus and Seth Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ↑ Budge (1969), Vol. I, 473-486.

- ↑ See Budge (1969); Dunand and Zivie-Coche (2004).

- ↑ See: Gail Paterson Corrington, "The Milk of Salvation: Redemption by the Mother in Late Antiquity and Early Christianity," The Harvard Theological Review 82:4 (October 1989), 393-420; Bruce M. Metzger, "Considerations of Methodology in the Study of the Mystery Religions and Early Christianity," The Harvard Theological Review 48:1 (January 1955), 1-20; Friedrich Solmsen, "George A. Wells on Christmas in Early New Testament Criticism," Journal of the History of Ideas 31:2 (April 1970), 277-280; Timothy E. Gregory, "The Survival of Paganism in Christian Greece: A Critical Essay," The American Journal of Philology 107:2 (Summer 1986), 229-242; Tom Harpur, The Pagan Christ: Recovering the Lost Light (Walker & Company, 2005, ISBN 0802714498); J. M. Robertson, Pagan Christs: Studies in Comparative Hierology (London: Watts, 1903).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Assmann, Jan. In search for God in ancient Egypt. Translated by David Lorton. Ithica: Cornell University Press, 2001. ISBN 0801487293

- Breasted, James Henry. Development of religion and thought in ancient Egypt. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986. ISBN 0812210454

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). The Egyptian Book of the Dead. 1895. Accessed at sacred-texts.com Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ———. The Egyptian Heaven and Hell. 1905. Accessed at sacred-texts.com Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ———. The gods of the Egyptians; or, Studies in Egyptian mythology. A Study in Two Volumes. New York: Dover Publications, 1969.

- ———. Legends of the Gods: The Egyptian texts. 1912. Accessed at sacred-texts.com Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ———. The Rosetta Stone. 1893, 1905. Accessed at sacred-texts.com Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- Collier, Mark and Bill Manly. How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs: Revised Edition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998. ISBN 0520239490

- Dunand, Françoise and Christiane Zivie-Coche. Gods and men in Egypt: 3000 B.C.E. to 395 C.E. Translated from the French by David Lorton. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004. ISBN 080144165X

- Erman, Adolf. A handbook of Egyptian religion. Translated by A. S. Griffith. London: Archibald Constable, 1907.

- Frankfort, Henri. Ancient Egyptian Religion. New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1961. ISBN 0061300772

- Griffith, F. Ll. and Herbert Thompson (translators). The Leyden Papyrus. 1904. Accessed at sacred-texts.com Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- Mancini, Anna. Ma'at Revealed: Philosophy of Justice in Ancient Egypt. New York: Buenos Books America, 2004. ISBN 1932848290

- Meeks, Dimitri and Christine Meeks-Favard. Daily life of the Egyptian gods. Translated from the French by G.M. Goshgarian. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996. ISBN 0801431158

- Mercer, Samuel A. B. (translator). The Pyramid Texts. 1952. Accessed online at sacred-texts.com Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- Pinch, Geraldine. Handbook of Egyptian mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2002. ISBN 1576072428

- Shafer, Byron E. (editor). Temples of ancient Egypt. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997. ISBN 0801433991

- Strudwick, Helen (General Editor). The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Singapore: De Agostini UK, 2006. ISBN 1904687997

- Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson, 2003. ISBN 0500051208

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.