Humphry Davy

|

Sir Humphry Davy | |

|---|---|

Sir Humphry Davy | |

| Born |

December 17, 1778 |

| Died | May 29, 1829 |

| Field | Physicist and Chemist |

| Institutions | Royal Institution |

| Notable students | Michael Faraday |

| Known for | Electrolysis, Chlorine, Davy lamp |

Sir Humphry Davy, 1st Baronet, FRS (December 17, 1778 – May 29, 1829) was an esteemed British chemist and physicist, who vastly expanded chemical knowledge by isolating and identifying a host of new chemical elements, and by linking the action of acids to hydrogen instead of oxygen. He was also an inventor, and the mentor of Michael Faraday, who for many years was Davy’s assistant and whose researches in electricity and magnetism formed the foundation for the modern understanding of the field of electromagnetism.

Biography

Davy was born in Penzance, Cornwall, United Kingdom, the son of Robert Davy and Grace Millett. He grew up in a household of humble means. When he turned 14, his parents managed to send him to Cardew’s school in Truro, where he put in a mixed performance. He left Cardew around the time of his father’s death, a year later, and, when he turned 17, was apprenticed to an apothecary. By age 19, he began more formal studies of chemistry and geometry. When he turned 20, he was appointed by a physician, Thomas Beddoes, as superintendent of the laboratory for the then newly established Medical Pneumatic Institution of Bristol. The purpose of the institute was to investigate medical applications for newly discovered “airs,” or gases such as oxygen, hydrogen, and carbon dioxide, the chemical properties of which were beginning to become known. His earliest researches, dating back to 1799, led to his first important discovery, the intoxicating effects of nitrous oxide, commonly known as laughing gas, which in modern times has been used as an anesthetic during surgery. This discovery, and the fame it brought, led to his invitation by scientist Benjamin Thompson (Count Rumford) (1753-1814), to head the laboratory at the Royal Institution in London. Upon taking up his duties, Davy immediately instituted a series of lectures on chemistry, which became very popular and increased his fame.

Electrochemistry work

The experiments of Luigi Galvani, accounts of which were published in 1791, showed that electricity could be generated by placing metal in contact with the nerves and muscles in a frog’s leg. This principle was taken up by Alessandro Volta between 1796 and 1800, which, combined with his own observations, led him to create the first electric battery. It was later shown that water and other substances could be decomposed into their constituent elements through chemical action at the poles of a battery. This discovery captured the interest of Davy, who had at his disposal at the Royal Institution just such a battery. As a result of preliminary experiments, Davy proposed that the action that brings two elements together to form a compound is electrical. He set about to create a table of the energies needed to decompose a number of compounds through electrolysis. These results, and Davy’s conclusions, were set forward in the Bakerian Lecture of 1806, and established the direction research in electrochemical action was to take for decades hence.

In 1807, Davy applied what was then one of the world's most powerful electric batteries to the decomposition of potassium and sodium salts, and succeeded in isolating the two metals and demonstrating that they were elements. The next year, using the same method, he isolated and identifying the elements calcium, magnesium, barium, and strontium. In 1810, using an improved and more powerful version of his voltaic battery, Davy produced an arc light using poles of carbon.

Chemists at this time believed, in accordance with the conclusions of Antoine Lavoisier, that acids were oxygen-based. But Davy’s investigation of hydrochloric acid (a compound of hydrogen and chlorine only), published in 1811, demonstrated that the compound contained no oxygen. He also clearly stated that chlorine, which at the time was thought to be a compound of hydrochloric acid and oxygen, was actually an element, and gave it the name it has today (Karl Wilhelm Scheele was the first to identify chlorine as a distinct gas in the 1770s, but it was thought to be an oxide of hydrochloric acid). This discovery led to the identification of iodine and flourine as elements as well, and to a new understanding of acids as hydrogen-based. Davy also demonstrated that oxygen was not always present in combustion, a conclusion that further undermined Lavoisier's theories on that subject.

Retirement and further work

In 1812, Davy was knighted by King George III, gave a farewell lecture to the Royal Institution, and married a wealthy widow, Jane Apreece. Later that year, Davy and his wife traveled through Scotland, but after their return to London, he was injured in an explosion in his laboratory while investigating a chemical compound of nitrogen and chlorine. It was this injury that caused Davy to hire Michael Faraday as a secretary. Only months later, Faraday was asked by Davy to assume the role of laboratory assistant at the Royal Institution.

By October 1813, Davy and his wife, accompanied by Faraday, who was also compelled to act as the couple’s valet, were on their way to France to collect a medal that Napoleon Bonaparte had awarded Davy for his electrochemical work. Whilst in Paris, Davy was shown a mysterious substance isolated by Barnard Courtois. Davy pronounced it to be an element, which is now called iodine.

In Florence, in a series of experiments, Davy, with Faraday's assistance, succeeded in using the sun's rays to ignite diamond, and proved that it was composed of pure carbon. The entourage also visited Volta.

Based on a series of lectures delivered at the request of the Board of Agriculture, Davy published Elements of Agricultural Chemistry, in 1813.

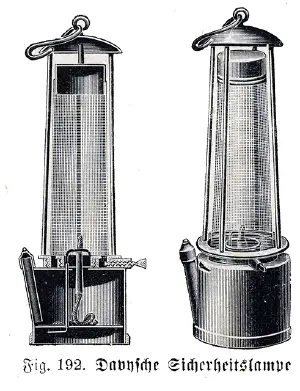

After his return to England in 1815, Davy invented the Davy lamp, a safe method of illumination used by miners. It was created for use in coal mines, allowing deep seams to be mined despite the presence of methane and other flammable gases, called firedamp or minedamp. Davy had discovered that a flame enclosed inside a mesh of a certain fineness cannot ignite firedamp. The screen acts as a flame arrestor; air (and any firedamp present) can pass through the mesh freely enough to support combustion, but the holes are too fine to allow a flame to propagate through them and ignite any firedamp outside the mesh. The first trial of a Davy lamp with a wire sieve was at Hebburn Colliery on 9 January 1816. He thought that this was one of his greatest achievements, but his claim to the invention, for which he demanded no royalties, was later challenged by George Stephenson.

Later years

In 1818, Davy was awarded a baronetcy and two years later became president of the Royal Society, a post he would hold until 1827.

In 1820s, Davy and his friend, William Hyde Wollaston, took up research in electricity and magnetism. Faraday also conducted research in the field, and published several papers, including one that demonstrated a way to create a motor from the magnetic force generated by a current-carrying wire. Davy felt that Faraday had taken credit for research that others had done, but Faraday refused to back down. This created friction between the two men, and apparently stalled Faraday’s research in the field, which he did not take up again until after Davy’s death. Davy was known to have been opposed to the election of Faraday as a fellow of the Royal Society, but Faraday was elected over his objections.

In 1824, Davy proposed, and eventually mounted chunks of iron to the hull of a copper clad ship, in the first use of cathodic protection. While this was effective in preventing the corrosion of copper, it eliminated the anti-fouling properties of the copper hull, leading to the attachment of molluscs and barnacles to the "protected" hull, slowing these ships and requiring extensive time in dry docks for defouling operations.

Davy’s mother died in 1826, and Davy took sick soon after. His illness worsened over time, but he continued to write, completing Hints and Experiments in Physical Science, and a memoir. As his physical condition deteriorated, he traveled to Europe, spending some time in Italy, where he was joined by his wife. Davy appeared to be making a recovery, and the couple went to Geneva, where Davy, unexpectedly, died in the early morning hours of May 29, 1829.

Legacy

Davy left many piecemeal contributions to chemistry, but no overarching theory to which he could lay claim. Perhaps his most important discoveries were his researches into the nature of chlorine, which not only proved that the gas was an element, but also shed new light on the nature of acids. His identification of interatomic forces with electricity was also an important milestone.

In his later years, as his career waned, he seemed to be more of an obstacle to progress than the cheerleader he was in earlier years. Throwing cold water on a protégé who would later be hailed as one of the greatest scientists that ever lived was not the best way to improve one’s image in posterity's light. It would seem that he got what he wanted out of his career, but in the end found it all wanting, in contrast to Faraday, for example, whose religious convictions led him to believe that he was more a servant of the divine than a self-promoter. Still, Davy’s hunger for experimental truth may have rubbed off on Faraday, who by the estimation of some commentators was said to have been the greatest experimental scientist of all time.

In memory of Davy

- In the town of Penzance, in Cornwall, a statue of Davy, its most famous son, stands in front of the imposing Market House at the top of Market Jew Street, the town's main high street.

- A secondary school in Penzance is named Humphry Davy School.

- A local pub in Penzance is named the Sir Humphry Davy pub. It is located at the end of Market Jew Street.

- The lunar crater Davy is named after Sir Humphry Davy. It has a diameter of 34 km and coordinates of 11.8S, 8.1W.

- The Davy Medal is given each year by the Royal Society of Great Britain for significant contemporary discovery in any branch of chemistry. It was established in 1877, and carries with it a £1000 prize

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gillespie, C. C. 1971. Dictionary of Scientific Biography. New York: Charles Scribner’s sons.

- Knight, David. 1992. Humphry Davy. Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell Publishers.

- "Sir Humphrey Davy," in Littell’s’ Living Age, Jan. 4, 1845, pp 3-17.

- Von Meyer, E. 1906. A History of Chemistry. London: MacMillan and Co.

External links

All links retrieved January 19, 2018.

- Works by Humphry Davy. Project Gutenberg.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.