Hydroelectricity

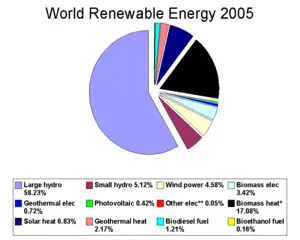

Hydroelectricity is electricity produced by hydropower—that is, the energy of moving water. It is the world's leading form of renewable energy. In 2005, it accounted for over 63 percent of the total renewable energy.[1] That same year, hydroelectricity supplied about 715,000 megawatts (or 19 percent) of the world's electricity (compared to 16 percent in 2003). Although large hydroelectric installations generate most of the world's hydroelectricity, small hydro schemes are particularly popular in China, which has over 50 percent of the world's small hydro capacity.

On the downside, hydroelectric projects can disrupt ecosystems by reducing access to salmon spawning grounds and damaging habitats of birds. These projects also lead to changes in the downstream river environment, by the scouring of river beds and loss of riverbanks. Large-scale hydroelectric dams, such as the Aswan Dam and the Three Gorges Dam, have created environmental problems both upstream and downstream.

Electricity generation

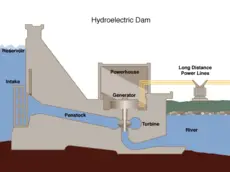

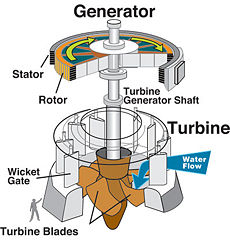

Most hydroelectric power comes from the potential energy of dammed water driving a water turbine and generator. In this case, the energy extracted from the water depends on the volume and on the difference in height between the source and the water's outflow. This height difference is called the head. The amount of potential energy in water is proportional to the head. To obtain very high head, water for a hydraulic turbine may be run through a large pipe called a penstock.

Pumped storage hydroelectricity produces electricity to supply high peak demands by moving water between reservoirs at different elevations. At times of low electrical demand, excess generation capacity is used to pump water into the higher reservoir. When there is higher demand, water is released back into the lower reservoir through a turbine. Pumped storage schemes currently provide the only commercially important means of grid energy storage and improve the daily load factor of the generation system.

Less common types of hydro schemes use water's kinetic energy or undammed sources such as run-of-the-river, waterwheels, and tidal power.

Industrial hydroelectric plants

Many hydroelectric projects supply public electricity networks, but some are created to serve specific industrial enterprises. Dedicated hydroelectric projects are often built to provide the substantial amounts of electricity needed for aluminium electrolytic plants, for example. In the Scottish Highlands there are examples at Kinlochleven and Lochaber, constructed during the early years of the twentieth century. In Suriname, the "van Blommestein" lake, dam and power station were constructed to provide electricity for the Alcoa aluminium industry. As of 2007 the Kárahnjúkar Hydropower Project in Iceland remains controversial.[2]

Advantages

Economics

The main advantage of hydroelectricity is that it is nearly independent of increases in the cost of fossil fuels such as oil, natural gas, or coal. Fuel is not required, and so it need not be imported. Hydroelectric plants tend to have longer economic lives than fuel-fired generation, with some plants now in service having been built 50 to 100 years ago. Operating labor cost is usually low since plants are automated and have few personnel on site during normal operation.

Where a dam serves multiple purposes, a hydroelectric plant may be added with relatively low construction cost, providing a useful revenue stream to offset the costs of dam operation. It has been calculated that the sale of electricity from the Three Gorges Dam will cover the construction costs after 5 to 7 years of full generation.[3]

Related activities

Reservoirs created by hydroelectric schemes often provide facilities for water sports, and become tourist attractions in themselves. In some countries, farming fish in the reservoirs is common. Multi-use dams installed for irrigation can support the fish farm with relatively constant water supply. Large hydro dams can control floods, which would otherwise affect people living downstream of the project. When dams create large reservoirs and eliminate rapids, boats may be used to improve transportation.

Greenhouse gas emissions

Since no fossil fuel is consumed, emission of carbon dioxide (a greenhouse gas) from burning fuel is eliminated. While some carbon dioxide is produced during manufacture and construction of the project, this is a tiny fraction of the operating emissions of equivalent fossil-fuel electricity generation. However, there may be other sources of emissions as discussed below.

Disadvantages

Environmental damage

Hydroelectric projects can be disruptive to surrounding aquatic ecosystems. For instance, studies have shown that dams along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of North America have reduced salmon populations by preventing access to spawning grounds upstream, even though most dams in salmon habitat have fish ladders installed. Salmon spawn are also harmed on their migration to sea when they must pass through turbines. This has led to some areas transporting smolt downstream by barge during parts of the year. Turbine and power-plant designs that are easier on aquatic life are an active area of research.

Generation of hydroelectric power changes the downstream river environment. Water exiting a turbine usually contains very little suspended sediment, which can lead to scouring of river beds and loss of riverbanks. Since turbines are often opened intermittently, rapid or even daily fluctuations in river flow are observed. For example, in the Grand Canyon, the daily cyclic flow variation caused by Glen Canyon Dam was found to be contributing to erosion of sand bars. Dissolved oxygen content of the water may change from pre-construction conditions. Water exiting from turbines is typically much colder than the pre-dam water, which can change aquatic faunal populations, including endangered species. Some hydroelectric projects also utilize canals, typically to divert a river at a shallower gradient to increase the head of the scheme. In some cases, the entire river may be diverted, leaving a dry riverbed. Examples include the Tekapo and Pukaki Rivers.

Large-scale hydroelectric dams, such as the Aswan Dam and the Three Gorges Dam, have created environmental problems both upstream and downstream.

A further concern is the impact of major schemes on birds. Since damming and redirecting the waters of the Platte River in Nebraska for agricultural and energy use, many native and migratory birds such as the Piping Plover and Sandhill Crane have become increasingly endangered.

Greenhouse gas emissions

The reservoirs of hydroelectric power plants in tropical regions may produce substantial amounts of methane and carbon dioxide. This is due to plant material in flooded areas decaying in an anaerobic environment, and forming methane, a very potent greenhouse gas. According to the World Commission on Dams report, where the reservoir is large compared to the generating capacity (less than 100 watts per square meter of surface area) and no clearing of the forests in the area was undertaken prior to impoundment of the reservoir, greenhouse gas emissions from the reservoir may be higher than those of a conventional oil-fired thermal generation plant.[5]

In boreal reservoirs of Canada and Northern Europe, however, greenhouse gas emissions are typically only 2 to 8 percent of any kind of conventional thermal generation. A new class of underwater logging operation that targets drowned forests can mitigate the effect of forest decay.[6]

Population relocation

Another disadvantage of hydroelectric dams is the need to relocate the people living where the reservoirs are planned. In many cases, no amount of compensation can replace ancestral and cultural attachments to places that have spiritual value to the displaced population. Additionally, historically and culturally important sites can be flooded and lost. Such problems have arisen at the Three Gorges Dam project in China, the Clyde Dam in New Zealand, and the Ilısu Dam in Southeastern Turkey.

Dam failures

Failures of large dams, while rare, are potentially serious—the Banqiao Dam failure in China resulted in the deaths of 171,000 people and left millions homeless, more than some estimates of the death toll from the Chernobyl disaster. Dams may be subject to enemy bombardment during wartime, sabotage, and terrorism. Smaller dams and micro hydro facilities are less vulnerable to these threats.

The creation of a dam in a geologically inappropriate location may cause disasters like the one of the Vajont Dam in Italy, where almost 2000 people died, in 1963.

Comparison with other methods of power generation

Hydroelectricity eliminates the flue gas emissions from fossil fuel combustion, including pollutants such as sulfur dioxide, nitric oxide, carbon monoxide, dust, and mercury in the coal.

Compared to the nuclear power plant, hydroelectricity generates no nuclear waste, nor nuclear leaks. Unlike uranium, hydroelectricity is also a renewable energy source.

Compared to wind farms, hydroelectricity power plants have a more predictable load factor. If the project has a storage reservoir, it can be dispatched to generate power when needed. Hydroelectric plants can be easily regulated to follow variations in power demand.

Unlike fossil-fueled combustion turbines, construction of a hydroelectric plant requires a long lead-time for site studies, hydrological studies, and environmental impact assessment. Hydrological data up to 50 years or more is usually required to determine the best sites and operating regimes for a large hydroelectric plant. Unlike plants operated by fuel, such as fossil or nuclear energy, the number of sites that can be economically developed for hydroelectric production is limited; in many areas the most cost effective sites have already been exploited. New hydro sites tend to be far from population centers and require extensive transmission lines. Hydroelectric generation depends on rainfall in the watershed, and may be significantly reduced in years of low rainfall or snowmelt. Utilities that primarily use hydroelectric power may spend additional capital to build extra capacity to ensure sufficient power is available in low water years.

Hydroelectric facts

In parts of Canada (the provinces of British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and Newfoundland and Labrador) hydroelectricity is used so extensively that the word "hydro" is used to refer to any electricity delivered by a power utility. The government-run power utilities in these provinces are called BC Hydro, Manitoba Hydro, Hydro One (formerly "Ontario Hydro"), Hydro-Québec, and Newfoundland and Labrador Hydro respectively. Hydro-Québec is the world's largest hydroelectric generating company, with a total installed capacity (2005) of 31,512 megawatts (MW).

Oldest hydroelectric power stations

- Cragside, Rothbury, England, completed 1870.

- Appleton, Wisconsin, U.S., completed 1882. A waterwheel on the Fox river supplied the first commercial hydroelectric power for lighting to two paper mills and a house, two years after Thomas Edison demonstrated incandescent lighting to the public. Within a matter of weeks of this installation, a power plant was also put into commercial service at Minneapolis.

- Duck Reach, Launceston, Tasmania. Completed 1895. The first publicly owned hydroelectric plant in the Southern Hemisphere. Supplied power to the city of Launceston for street lighting.

- Decew Falls 1, St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada, completed August 25, 1898. Owned by Ontario Power Generation. Four units are still operational. Recognized as an IEEE Milestone in Electrical Engineering & Computing by the IEEE Executive Committee in 2002.

- It is believed that the oldest Hydro Power site in the United States is located on Claverack Creek, in Stottville, New York. The turbine, a Morgan Smith, was constructed in 1869, and installed 2 years later. It is one of the earliest water wheel installations in the United States and also generated electricity. It is owned today by Edison Hydro.

- The oldest continuously operated commercial hydroelectric plant in the United States is built on the Hudson River at Mechanicville, New York. The seven 750 kW units at this station initially supplied power at a frequency of 38 Hz, but later were increased in speed to 40 Hz. It went into commercial service July 22,1898. It is now being restored to its original condition and remains in commercial operation. [7]

Countries with the most hydroelectric capacity

The ranking of hydroelectric capacity is either by actual annual energy production or by installed capacity power rating. A hydroelectric plant rarely operates at its full power rating over a full year; the ratio between annual average power and installed capacity rating is the load factor. The installed capacity is the sum of all generator nameplate power ratings.

| Country | Annual Hydroelectric Energy Production | Installed Capacity | Load Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| People's Republic of China | 416,700 Gigawatt hours (GWh) | 128,570 MW | 0,37 |

| Canada | 356,930 GWh | 68,974 MW | 0,59 |

| Brazil | 336,800 GWh | 69,080 MW | 0,56 |

| USA | 289,980 GWh | 79,511 MW | 0,42 |

| Russia | 167,000 GWh | 45,000 MW | 0,42 |

| India | 125,126 GWh | 33,600 MW | 0,43 |

| Norway | 119,000 GWh | 27,528 MW | 0,49 |

| Japan | 88,500 GWh | 27,229 MW | 0,37 |

| France | 56,100 GWh | 25,335 MW | 0,25 |

Country, annual hydroelectricity production, installed capacity (2006 data including pumped storage schemes)

Largest hydroelectric power stations

The La Grande Complex in Quebec, Canada, is the world's largest hydroelectric generating system. The eight generating stations of the complex have a total generating capacity of 16,021 MW. The Robert Bourassa station alone has a capacity of 5,616 MW. A ninth station (Eastmain-1) is currently under construction and will add 480 MW to the total. Construction on an additional project on the Rupert River was started on January 11, 2007. It will add two stations with a combined capacity of 888 MW.

| Name | Country | Year of completion | Total Capacity | Max annual electricity production |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Itaipú | Brazil/Paraguay | 1984/1991/2003 | 14,000 MW | 93.4 TeraWatt (TW)-hours |

| Three Gorges Dam | China | 2004* | 11,200 MW (July 2007); 22,500 MW (when complete) | 84.7 TW-hours |

| Guri | Venezuela | 1986 | 10,200 MW | 46 TW-hours |

| Grand Coulee | United States | 1942/1980 | 6,809 MW | 22.6 TW-hours |

| Sayano Shushenskaya | Russia | 1983 | 6,721 MW | 23.6 TW-hours |

| Krasnoyarskaya | Russia | 1972 | 6,000 MW | 20.4 TW-hours |

| Robert-Bourassa | Canada | 1981 | 5,616 MW | |

| Churchill Falls | Canada | 1971 | 5,429 MW | 35 TW-hours |

| Bratskaya | Russia | 1967 | 4,500 MW | 22.6 TW-hours |

| Ust Ilimskaya | Russia | 1980 | 4,320 MW | 21.7 TW-hours |

| Tucurui | Brazil | 1984 | 4,240 MW | |

| Yaciretá | Argentina/Paraguay | 1998 | 4,050 MW | 19.2 TW-hours |

| Ertan Dam | China | 1999 | 3,300 MW (550MW×6) | 17.0 TW-hours |

| Gezhouba Dam | China | 1988 | 3,115 MW | 17.01 TW-hours |

| Nurek Dam | Tajikistan | 1979/1988 | 3,000 MW | |

| La Grande-4 | Canada | 1986 | 2,779 MW | |

| W. A. C. Bennett Dam | Canada | 1968 | 2,730 MW | |

| Chief Joseph Dam | United States | 1958/73/79 | 2,620 MW | |

| Volzhskaya (Volgogradskaya) | Russia | 1961 | 2,541 MW | 12.3 TW-hours |

| La Grande-3 | Canada | 1984 | 2,418 MW | |

| Atatürk Dam | Turkey | 1990 | 2,400 MW | |

| Zhiguliovskaya (Samarskaya) | Russia | 1957 | 2,300 MW | 10.5 TW-hours |

| Iron Gates | Romania/Serbia | 1970 | 2,280 MW | 11.3 TW-hours |

| John Day Dam | United States | 1971 | 2,160 MW | |

| La Grande-2-A | Canada | 1992 | 2,106 MW | |

| Aswan | Egypt | 1970 | 2,100 MW | |

| Tarbela Dam | Pakistan | 1976 | 2,100 MW | |

| Hoover Dam | United States | 1936/1961 | 2,080 MW | |

| Cahora Bassa | Mozambique | 1975 | 2,075 MW | |

| Karun III Dam | Iran | 2007 | 2,000 MW | 4.1 TW-hours |

* Powered first 14 water turbogenerators

Major schemes in progress

| Name | Maximum Capacity | Country | Construction started | Scheduled completion | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Three Gorges Dam | 22,400 MW | China | December 14 1994 | 2009 | Largest power plant in the world. First power in July 2003, with 10,500MW installed by June 2007. |

| Xiluodu Dam | 12,600 MW | China | December 26 2005 | 2015 | |

| Baihetan Dam | 12,000 MW | China | 2009 | 2015 | Still in planning |

| Wudongde Dam | 7,000 MW | China | 2009 | 2015 | Still in planning |

| Longtan Dam | 6,300 MW | China | July 1 2001 | December 2009 | |

| Xiangjiaba Dam | 6,000 MW | China | November 26 2006 | 2009 | |

| Jinping 2 Hydropower Station | 4,800 MW | China | January 30 2007 | 2014 | To build this dam, only 23 families and 129 local residents need to be moved. It works with Jinping 1 Hydropower Station as a group. |

| Laxiwa Dam | 4,200 MW | China | April 18 2006 | 2010 | |

| Xiaowan Dam | 4,200 MW | China | January 1 2002 | December 2012 | |

| Jinping 1 Hydropower Station | 3,600 MW | China | November 11 2005 | 2014 | |

| Pubugou Dam | 3,300 MW | China | March 30 2004 | 2010 | |

| Goupitan Dam | 3,000 MW | China | November 8 2003 | 2011 | |

| Boguchan Dam | 3,000 MW | Russia | 1980 | 2012 | |

| Son la Dam | 2,400 MW | Vietnam | 2005 | ||

| Bureya Dam | 2,010 MW | Russia | 1978 | 2009 | |

| Ilısu Dam | 1,200 MW | Turkey | August 5 2006 | 2013 | one of the Southeastern Anatolia Project Dams in Turkey |

Those 10 dams in China will have total generating capacity of 70,400 MW (70.2 gigawatt (GW)) when completed. For comparison purposes, in 1999, the total capacity of hydroelectric generators in Brazil, the third country by hydroelectric capacity, was 57.52 GW.

Notes

- ↑ REN21, Renewables Global Status Report 2006 Update. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ Saving Iceland, Summer of International dissent against Heavy Industry. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ International Water Power and Dam Construction, Beyond Three Gorges in China. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ Ontario Power Generation, Stay Clear, Stay Safe. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ Duncan Graham-Rowe, Hydroelectric power's dirty secret revealed, New Scientist. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ Inhabitant, “REDISCOVERED” WOOD & THE TRITON SAWFISH. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ IEEE Industry Applications Magazine, "The Historic Mechanicville Hydroelectric Station Part 1: The Early Days," Jan/Feb. 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dales, J. H. 1957. Hydroelectricity and Industrial Development: Quebec, 1898-1940. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Graham-Rowe, Duncan. 2005. New Scientist report on greenhouse gas production by hydroelectric dams. New Scientist. Retrieved on July 24, 2007.

- Manore, Jean L. 1999. Cross-Currents: Hydroelectricity and the Engineering of Northern Ontario. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 0889203172

- Tremblay, A., Louis Varfalvy, Charlotte Roehm, and Michelle Garneau. 2005. Greenhouse Gas Emissions—Fluxes and Processes: Hydroelectric Reservoirs and Natural Environments. New York: Springer. ISBN 3540234551

- Wilmington Media LTD. 2007. International Water Power and Dam Construction Venezuela country profile. International Water Power and Dam Construction. Retrieved on July 24, 2007.

- Wilmington Media LTD. 2007. International Water Power and Dam Construction Canada country profile. International Water Power and Dam Construction. Retrieved on July 24, 2007.

External links

All links retrieved January 22, 2018.

- National Hydropower Association, USA.

- University of Washington Libraries – Seattle Power and Water Supply Collection.

- United States Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC).

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.