Hypnosis

Hypnosis is a natural psychological process in which critical thinking faculties of the human mind are bypassed and a type of selective thinking, attention, and perception is established. There is reduced peripheral awareness, and an enhanced capacity to respond to suggestion.

There are competing theories explaining hypnosis and related phenomena. "Altered state" theories see hypnosis as an altered state of mind or trance, marked by a level of awareness different from the ordinary state of consciousness. In contrast, "non-state" theories see hypnosis as, variously, a type of placebo effect, a redefinition of an interaction with a therapist, or a form of imaginative role enactment.

While hypnosis has a well-documented and effective clinical application in hypnotherapy, there are more controversial but mostly harmless applications, such as stage hypnosis which functions as entertainment, and past life regression that uses hypnosis to recover what practitioners believe are memories of past lives or incarnations. The use of hypnosis to recover repressed memories in cases of alleged Child abuse, however, is deemed not only controversial but potentially dangerous.

Etymology

The words hypnosis and hypnotism both derive from the term neuro-hypnotism (nervous sleep), all of which were coined by Étienne Félix d'Henin de Cuvillers in the 1820s. The term hypnosis is derived from the ancient Greek ὑπνος hypnos, "sleep", and the suffix -ωσις -osis, or from ὑπνόω hypnoō, "put to sleep" (stem of aorist hypnōs-) and the suffix -is.[1] These words were popularized in English by the Scottish surgeon James Braid (to whom they are sometimes wrongly attributed) around 1841. Braid based his practice on that developed by Franz Mesmer and his followers (which was called "Mesmerism" or "animal magnetism"), but differed in his theory as to how the procedure worked.

Definition

A formal definition of hypnosis and related terms, derived from academic psychology, was provided in 2014, when the Society for Psychological Hypnosis, Division 30 of the American Psychological Association (APA), published the following official definitions:

- Hypnosis: A state of consciousness involving focused attention and reduced peripheral awareness characterized by an enhanced capacity for response to suggestion.

- Hypnotic Induction: A procedure designed to induce hypnosis.

- Hypnotizability: An individual’s ability to experience suggested alterations in physiology, sensations, emotions, thoughts or behavior during hypnosis.

- Hypnotherapy: The use of hypnosis in the treatment of a medical or psychological disorder or concern.[2]

History

Hypnosis has a long history from ancient times; people have been entering into hypnotic-type trances for thousands of years. In many cultures and religions, it was regarded as a form of meditation. The earliest record of a description of a hypnotic state can be found in the writings of Avicenna, a Persian physician who wrote about "trance" in 1027.[3] Its current uses have been studied scientifically by a host of both practitioners and researchers.

Sleep temples

Hypnotism as a tool for health seems to have originated with the use of sleep temples. Hindus of India often took their sick to sleep temples to be cured by hypnotic suggestion. The Law of Manu, which was the ancient Sanskrit text on how society should be run, categorized different states of hypnosis: the "Sleep-Waking" state, the "Dream-Sleep" state, and the "Ecstasy-Sleep" state. Hypnotic-like inductions were used to place the individual in a sleep-like state.

In Egypt, sleep temples (also known as dream temples) functioned as hospitals, healing a variety of ailments, perhaps many of them psychological in nature. Patients were taken to an unlit chamber to sleep and be treated for their specific ailment.The treatment involved chanting, placing the patient into a trance-like or hypnotic state, and analyzing their dreams in order to determine treatment. Meditation, fasting, baths, and sacrifices to the patron deity or other spirits were often involved as well.

Sleep temples also existed in Ancient Greece where they were called Asclepieions, built in honor of Asclepios the Greek god of medicine. The Greek treatment was referred to as incubation and focused on prayers to Asclepios for healing. These sleep chambers were filled with snakes, the symbol of the rod of Asclepios, the serpent-entwined rod that symbolizes medicine to this day.

Magnetism

Paracelsus (1493-1541) was the first physician to utilize magnets in his work. Many people claimed to be healed after he passed magnets (or lodestones) over their body. Around 1771, a Viennese Jesuit named Maximilian Hell (1720-1792) used magnets to heal by applying steel plates to the naked body. One of Father Hell's students was a young medical doctor from Vienna named Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815).

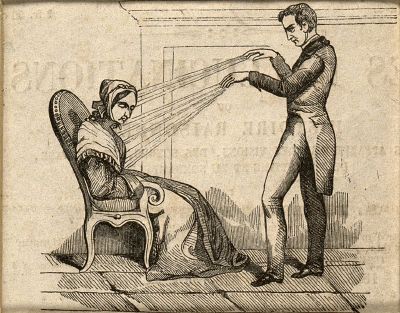

Western scientists first became involved in hypnosis around 1770, when Mesmer started investigating an effect he called "animal magnetism" or "mesmerism." Mesmer found that, after opening a patient's vein and letting the patient bleed for a while, by passing magnets over the wound it would stop bleeding. Mesmer held the opinion that hypnosis was a sort of mystical force that flows from the hypnotist to the person being hypnotized, but his theory was dismissed by critics who asserted that there is no magical element to hypnotism.

In the early nineteenth century, an Indo-Portuguese priest, Abbé Faria (1756-1819), revived public attention in animal magnetism by introducing hypnosis to Paris. Unlike Mesmer, Faria claimed that it 'generated from within the mind’ by the power of expectancy and cooperation of the patient.

Early medical research

The evolution of Mesmer's ideas and practices led James Braid (1795-1860) to develop the procedure known as hypnosis in 1842. Known as the "Father of Modern Hypnotism," Braid rejected Mesmer's idea of magnetism inducing hypnosis, and ascribed the creation of the 'mesmeric trance' to a physiological process—the prolonged attention on a bright moving object or similar object of fixation. He postulated that "protracted ocular fixation" fatigued certain parts of the brain and caused the trance, "nervous sleep." In 1843, he published his Neurypnology: or the Rationale of Nervous Sleep, calling the procedure "neuro-hypnosis."[4] Believing sleep was involved, he used terms such as "hypnosis" and "hypnotist." Later, realizing that "hypnosis" was not sleep, he tried to change the name to monoideaism ("single-thought-ism") but it was too late as the term "hypnosis" had stuck.

Some in the medical establishment became interested in applications of hypnosis, using it to allow patients to be operated on without pain. For example, James Esdaile (1805-1859) reported on 345 major operations performed using mesmeric sleep as the sole anesthetic in British India. However, the development of chemical anesthetics soon saw the replacement of hypnotism in this role.

In the 1840s and 1850s, Carl Reichenbach began experiments to find any scientific validity to "mesmeric" energy. Although his conclusions were quickly rejected in the scientific community, they did undermine Mesmer's claims of mind control. In 1846, James Braid published an influential article, "The Power of the Mind over the Body," attacking Reichenbach's views as pseudo-scientific.[5]

The deaths of Braid and Esdaile curbed interest in hypnotism. Experimentation was revived into the 1880s, mainly in continental Europe where new translations of Braid's work were circulated.

Early psychological studies

For several decades Braid's work became more influential abroad than in his own country. The French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893) endorsed hypnotism for the treatment of hysteria, which led to a number of systematic experimental examinations of hypnosis in France, Germany, and Switzerland. The process of post-hypnotic suggestion was first described in this period.

France became the focal point for the study of Braid's ideas after the eminent neurologist Étienne Eugène Azam translated Braid's last manuscript (On Hypnotism, 1860) into French and presented Braid's research to the French Academy of Sciences.[6] At the request of Azam, Paul Broca, and others, the French Academy of Science, which had investigated Mesmerism in 1784, examined Braid's writings shortly after his death. Azam's enthusiasm for hypnotism influenced Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault, a country doctor, who was successful in using hypnosis in his clinic. He wrote of the necessity of rapport between the hypnotizer and the participant, and emphasized the importance of suggestibility. Hippolyte Bernheim discovered Liébeault's enormously popular group hypnotherapy clinic in Nancy (known as the "Nancy School"), and also became an influential hypnotist.

The study of hypnotism subsequently revolved around the fierce debate between Bernheim and Jean-Martin Charcot. Charcot argued that hypnotism was an abnormal state of nervous functioning found only in certain hysterical women. He claimed that it manifested in a series of physical reactions that could be divided into distinct stages. Bernheim argued that anyone could be hypnotized, that it was an extension of normal psychological functioning, and that its effects were due to suggestion.

Pierre Janet (1859–1947), Charcot's student, was appointed director of the psychological laboratory at the Salpêtrière in 1889, later he became a lecturer in psychology at the Sorbonne and then chair of experimental and comparative psychology at the Collège de France. Janet reconciled elements of Charcot's views with those of Bernheim and his followers, developing his own sophisticated hypnotic psychotherapy based upon the concept of psychological dissociation. Janet described dissociation as the splitting of mental aspects under hypnosis (or hysteria) so skills and memory could be made inaccessible or recovered. His work provoked interest in the subconscious and laid the framework for reintegration therapy for dissociated personalities.

Émile Coué (1857–1926) began by practicing at Liébeault and Bernheim's Nancy School. However, he abandoned their approach altogether and developed a new approach (c.1901) based on Braid-style direct hypnotic suggestion and ego-strengthening. Coué's method did not emphasize "sleep" or deep relaxation, but instead focused upon autosuggestion involving a specific series of suggestion tests. Coué's method became a renowned self-help and psychotherapy technique, which contrasted with psychoanalysis and prefigured self-hypnosis and cognitive therapy.

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), the founder of psychoanalysis, studied hypnotism at the Paris School and briefly visited the Nancy School. At first, Freud was an enthusiastic proponent of hypnotherapy. He "initially hypnotised patients and pressed on their foreheads to help them concentrate while attempting to recover (supposedly) repressed memories,"[7] and he soon began to emphasize hypnotic regression and ab reaction (catharsis) as therapeutic methods. He published an influential series of case studies with his colleague Joseph Breuer, entitled Studies on Hysteria (1895),[8] which became the founding text of the subsequent tradition known as "hypno-analysis" or "regression hypnotherapy."

However, Freud gradually abandoned hypnotism in favor of psychoanalysis, emphasizing free association and interpretation of the unconscious. Struggling with the great expense of time that psychoanalysis required, Freud later suggested that it might be combined with hypnotic suggestion to hasten the outcome of treatment, but that this would probably weaken the outcome: "It is very probable, too, that the application of our therapy to numbers will compel us to alloy the pure gold of analysis plentifully with the copper of direct [hypnotic] suggestion."[9]

The next major development came from behavioral psychology in American university research. Clark L. Hull (1884–1952) published the first major compilation of laboratory studies on hypnosis, Hypnosis and Suggestibility (1933)[10] in which he proved that hypnosis and sleep had nothing in common. Hull published many quantitative findings from hypnosis and suggestion experiments and encouraged research by mainstream psychologists. Hull's behavioral psychology interpretation of hypnosis, emphasizing conditioned reflexes, rivaled the Freudian psycho-dynamic interpretation which emphasized unconscious transference.

Milton Erickson (1901–1980), the founding president of the American Society for Clinical Hypnosis, was one of the most influential post-war hypnotherapists. During the 1960s, Erickson popularized a new branch of hypnotherapy, known as Ericksonian therapy, characterized primarily by indirect suggestion, "metaphor" (actually analogies), confusion techniques, and double binds in place of formal hypnotic inductions. However, the difference between Erickson's methods and traditional hypnotism led contemporaries to questions about whether he was practicing hypnosis at all:

Erickson had no hesitation in presenting any suggested effect as being "hypnosis," whether or not the subject was in a hypnotic state. In fact, he was not hesitant in passing off behaviour that was dubiously hypnotic as being hypnotic.[11]

However, during numerous witnessed and recorded encounters in clinical, experimental, and academic settings Erickson was able to evoke examples of classic hypnotic phenomena such as positive and negative hallucinations, anesthesia, analgesia (in childbirth and even terminal cancer patients), catalepsy, regression to provable events in subjects' early lives, and even into infantile reflexology. Erickson stated in his own writings that there was no correlation between hypnotic depth and therapeutic success and that the quality of the applied psychotherapy outweighed the need for deep hypnosis in many cases. Hypnotic depth was to be pursued for research purposes.[12]

At the outset of cognitive behavioral therapy during the 1950s, hypnosis was used by early behavior therapists such as Joseph Wolpe[13] and also by early cognitive therapists such as Albert Ellis,[14] thus expanding the use of hypnosis as a therapeutic technnique.

Methodologies

Induction

Hypnosis is normally preceded by a "hypnotic induction" technique. Traditionally, this was interpreted as a method of putting the subject into a "hypnotic trance"; however, subsequent "nonstate" theorists have viewed it differently, seeing it as a means of heightening client expectation, defining their role, focusing attention, and so on.

There are several different induction techniques. One of the most influential methods was Braid's "eye-fixation" technique, also known as "Braidism." Many variations of the eye-fixation approach exist, including the induction used in the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale (SHSS), the most widely used research tool in the field of hypnotism.[15] Braid's original description of his induction is as follows:

Take any bright object (e.g. a lancet case) between the thumb and fore and middle fingers of the left hand; hold it from about eight to fifteen inches from the eyes, at such position above the forehead as may be necessary to produce the greatest possible strain upon the eyes and eyelids, and enable the patient to maintain a steady fixed stare at the object.

The patient must be made to understand that he is to keep the eyes steadily fixed on the object, and the mind riveted on the idea of that one object. It will be observed, that owing to the consensual adjustment of the eyes, the pupils will be at first contracted: They will shortly begin to dilate, and, after they have done so to a considerable extent, and have assumed a wavy motion, if the fore and middle fingers of the right hand, extended and a little separated, are carried from the object toward the eyes, most probably the eyelids will close involuntarily, with a vibratory motion. If this is not the case, or the patient allows the eyeballs to move, desire him to begin anew, giving him to understand that he is to allow the eyelids to close when the fingers are again carried towards the eyes, but that the eyeballs must be kept fixed, in the same position, and the mind riveted to the one idea of the object held above the eyes. In general, it will be found, that the eyelids close with a vibratory motion, or become spasmodically closed.[16]

Braid later acknowledged that the hypnotic induction technique was not necessary in every case, and subsequent researchers have generally found that on average it contributes less than previously expected to the effect of hypnotic suggestions.[17] Variations and alternatives to the original hypnotic induction techniques were subsequently developed.

Suggestion

When Braid first described hypnotism, he did not use the term "suggestion" but referred instead to the act of focusing the conscious mind of the subject upon a single dominant idea. Braid's main therapeutic strategy involved stimulating or reducing physiological functioning in different regions of the body. In his later works, however, Braid placed increasing emphasis upon the use of a variety of different verbal and non-verbal forms of suggestion, including the use of "waking suggestion" and self-hypnosis. Subsequently, Hippolyte Bernheim shifted the emphasis from the physical state of hypnosis on to the psychological process of verbal suggestion:

I define hypnotism as the induction of a peculiar psychical [i.e., mental] condition which increases the susceptibility to suggestion. Often, it is true, the [hypnotic] sleep that may be induced facilitates suggestion, but it is not the necessary preliminary. It is suggestion that rules hypnotism.[18]

Bernheim's conception of the primacy of verbal suggestion in hypnotism dominated the subject throughout the twentieth century, leading some authorities to declare him the father of modern hypnotism.[19]

Contemporary hypnotism uses a variety of suggestion forms including direct verbal suggestions, "indirect" verbal suggestions such as requests or insinuations, metaphors and other rhetorical figures of speech, and non-verbal suggestion in the form of mental imagery, voice tonality, and physical manipulation. A distinction is commonly made between suggestions delivered "permissively" and those delivered in a more "authoritarian" manner. Harvard hypnotherapist Deirdre Barrett writes that most modern research suggestions are designed to bring about immediate responses, whereas hypnotherapeutic suggestions are usually post-hypnotic ones that are intended to trigger responses affecting behavior for periods ranging from days to a lifetime in duration. The hypnotherapeutic ones are often repeated in multiple sessions before they achieve peak effectiveness.[20]

Some hypnotists view suggestion as a form of communication that is directed primarily to the subject's conscious mind, whereas others view it as a means of communicating with the "unconscious" or "subconscious" mind.[21] These concepts were introduced into hypnotism at the end of the nineteenth century by Sigmund Freud and Pierre Janet. Sigmund Freud's psychoanalytic theory describes conscious thoughts as being at the surface of the mind and unconscious processes as being deeper in the mind. Braid, Bernheim, and other Victorian pioneers of hypnotism did not refer to the unconscious mind but saw hypnotic suggestions as being addressed to the subject's conscious mind. Indeed, Braid actually defined hypnotism as focused (conscious) attention upon a dominant idea (or suggestion).

Hypnotists who believe that responses are mediated primarily by an "unconscious mind," like Milton Erickson, make use of indirect suggestions such as metaphors or stories whose intended meaning may be concealed from the subject's conscious mind. By contrast, hypnotists who believe that responses to suggestion are primarily mediated by the conscious mind, such as Theodore Barber and Nicholas Spanos, have tended to make more use of direct verbal suggestions and instructions.

Ideo-dynamic reflex

The first neuropsychological theory of hypnotic suggestion was introduced early by James Braid who adopted his friend and colleague William Carpenter's theory of the ideo-motor reflex response to account for the phenomenon of hypnotism. Carpenter had observed from close examination of everyday experience that, under certain circumstances, the mere idea of a muscular movement could be sufficient to produce a reflexive, or automatic, contraction or movement of the muscles involved, albeit in a very small degree. Braid extended Carpenter's theory to encompass the observation that a wide variety of bodily responses besides muscular movement can be thus affected, for example, the idea of sucking a lemon can automatically stimulate salivation, a secretory response. Braid, therefore, adopted the term "ideo-dynamic," meaning "by the power of an idea," to explain a broad range of "psycho-physiological" (mind–body) phenomena.

Braid coined the term "mono-ideodynamic" to refer to the theory that hypnotism operates by concentrating attention on a single idea in order to amplify the ideo-dynamic reflex response. Variations of the basic ideo-motor, or ideo-dynamic, theory of suggestion have continued to exercise considerable influence over subsequent theories of hypnosis, including those of Clark L. Hull, Hans Eysenck, and Ernest Rossi.[21]

Theories of Hypnosis

The central theoretical disagreement regarding hypnosis is known as the "state versus nonstate" debate. When Braid introduced the concept of hypnotism, he equivocated over the nature of the "state," sometimes describing it as a specific sleep-like neurological state comparable to animal hibernation or yogic meditation, while at other times he emphasized that hypnotism encompasses a number of different stages or states that are an extension of ordinary psychological and physiological processes.

State theorists interpret the effects of hypnotism as due primarily to a specific, abnormal, and uniform psychological or physiological state of some description, often referred to as "hypnotic trance" or an "altered state of consciousness." Nonstate theorists rejected the idea of hypnotic trance and interpret the effects of hypnotism as due to a combination of multiple task-specific factors derived from normal cognitive, behavioral, and social psychology, such as social role-perception and favorable motivation (Sarbin), active imagination and positive cognitive set (Barber), response expectancy (Kirsch), and the active use of task-specific subjective strategies (Spanos). The personality psychologist Robert White is often cited as providing one of the first nonstate definitions of hypnosis in his 1941 article:

Hypnotic behavior is meaningful, goal-directed striving, its most general goal being to behave like a hypnotized person as this is continuously defined by the operator and understood by the client.[22]

Hyper-suggestibility

Braid's later writings can be taken to imply that hypnosis is largely a state of heightened suggestibility induced by expectation and focused attention. In particular, Hippolyte Bernheim became known as the leading proponent of the "suggestion theory" of hypnosis, at one point going so far as to declare that there is no hypnotic state, only heightened suggestibility. There is a general consensus that heightened suggestibility is an essential characteristic of hypnosis. In 1933, Clark L. Hull wrote:

If a subject after submitting to the hypnotic procedure shows no genuine increase in susceptibility to any suggestions whatever, there seems no point in calling him hypnotized, regardless of how fully and readily he may respond to suggestions of lid-closure and other superficial sleeping behavior.[23]

Conditioned inhibition

Ivan Pavlov stated that hypnotic suggestion provided the best example of a conditioned reflex response in human beings; in other words, that responses to suggestions were learned associations triggered by the words used:

Speech, on account of the whole preceding life of the adult, is connected up with all the internal and external stimuli which can reach the cortex, signaling all of them and replacing all of them, and therefore it can call forth all those reactions of the organism which are normally determined by the actual stimuli themselves. We can, therefore, regard "suggestion" as the most simple form of a typical conditioned reflex in man.[24]

Pavloc also believed that hypnosis was a "partial sleep," meaning that a generalized inhibition of cortical functioning could be encouraged to spread throughout regions of the brain. He observed that the various degrees of hypnosis did not significantly differ physiologically from the waking state and hypnosis depended on insignificant changes of environmental stimuli. Pavlov also suggested that lower-brain-stem mechanisms were involved in hypnotic conditioning.[25]

Neuropsychology

Changes in brain activity have been found in some studies of highly responsive hypnotic subjects. These changes vary depending upon the type of suggestions being given. However, what these results indicate is unclear. They may indicate that suggestions genuinely produce changes in perception or experience that are not simply the result of imagination. However, in normal circumstances without hypnosis, the brain regions associated with motion detection are activated both when motion is seen and when motion is imagined, without any changes in the subjects' perception or experience. This may therefore indicate that highly suggestible hypnotic subjects are simply activating to a greater extent the areas of the brain used in imagination, without real perceptual changes. A 2004 review of research examining the EEG laboratory work in this area concludes:

Hypnosis is not a unitary state and therefore should show different patterns of EEG activity depending upon the task being experienced. In our evaluation of the literature, enhanced theta is observed during hypnosis when there is task performance or concentrative hypnosis, but not when the highly hypnotizable individuals are passively relaxed, somewhat sleepy and/or more diffuse in their attention.[26]

Dissociation

Pierre Janet originally developed the idea of dissociation of consciousness from his work with hysterical patients. He believed that hypnosis was an example of dissociation, whereby areas of an individual's behavioral control separate from ordinary awareness. Hypnosis would remove some control from the conscious mind, and the individual would respond with autonomic, reflexive behavior. Weitzenhoffer describes hypnosis via this theory as "dissociation of awareness from the majority of sensory and even strictly neural events taking place."[19]

Neodissociation

Ernest Hilgard, who developed the "neodissociation" theory of hypnotism, hypothesized that hypnosis causes the subjects to divide their consciousness voluntarily. One part responds to the hypnotist while the other retains awareness of reality. For example, when Hilgard made his subjects take an ice water bath under hypnosis none mentioned the water being cold or feeling pain. However, when he asked them to lift their index finger if they felt pain, 70 percent of these subjects lifted their index finger. Hilgard interpreted this as showing that the subjects were listening to the suggestive hypnotist but with another part of their consciousness they were aware of the water's temperature.[27]

Social role-taking theory

Theodore Sarbin pioneered the role-taking theory of hypnotism. He argued that hypnotic responses were motivated attempts to fulfill the socially constructed roles of hypnotic subjects. This has led to the misconception that hypnotic subjects are simply "faking." However, Sarbin emphasized the difference between faking, in which there is little subjective identification with the role in question, and role-taking, in which the subject not only acts externally in accord with the role but also subjectively identifies with it to some degree, acting, thinking, and feeling "as if" they are hypnotized. Sarbin drew analogies between role-taking in hypnosis and role-taking in other areas such as method acting, mental illness, and shamanic possession. This interpretation of hypnosis is particularly relevant to understanding stage hypnosis, in which there is strong peer pressure to comply with a socially constructed role by performing accordingly on a theatrical stage.

Hence, the social constructionism and role-taking theory of hypnosis suggests that individuals are enacting (as opposed to merely "playing") a role and that really there is no such thing as a hypnotic trance. A socially constructed relationship is built depending on how much rapport has been established between the "hypnotist" and the subject.

Similarly, Robert Baker and Graham Wagstaff claim that what we call hypnosis is actually a form of learned social behavior, a complex hybrid of social compliance, relaxation, and suggestibility that can account for many esoteric behavioral manifestations.[28]

Cognitive-behavioral theory

Barber, Spanos, and Chaves proposed a nonstate "cognitive-behavioral" theory of hypnosis, similar in some respects to Sarbin's social role-taking theory. In this model, hypnosis is explained as an extension of ordinary psychological processes like imagination, relaxation, expectation, social compliance, and so forth. In particular, Barber argued that responses to hypnotic suggestions were mediated by a "positive cognitive set" consisting of positive expectations, attitudes, and motivation. Daniel Araoz subsequently coined the acronym "TEAM" to symbolize the subject's orientation to hypnosis in terms of "trust," "expectation," "attitude," and "motivation."[17]

They noted that similar factors appeared to mediate the response both to hypnotism and to cognitive behavioral therapy, in particular systematic desensitization.[17] Inspired by their work, research and clinical practice has led to growing interest in the relationship between hypnotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy.[29]

Systems theory

Systems theory considers the nervous system's organization into interacting subsystems. Hypnotic phenomena thus involve not only increased or decreased activity of particular subsystems, but also their interaction. In this context, systems theory may be regarded as an extension of Braid's original conceptualization of hypnosis as involving "the brain and nervous system generally."[4]

Applications

There are numerous applications for hypnosis across multiple fields of interest, including medical/psychotherapeutic uses, military uses, self-improvement, and entertainment.

Hypnotism has also been used in forensics, sports, education, physical therapy, and rehabilitation.[11] Hypnotism has also been employed by artists for creative purposes, most notably the surrealist circle of André Breton who employed hypnosis, automatic writing, and sketches for creative purposes.

Hypnotherapy

Hypnotherapy is the use of hypnosis in a therapeutic context, either as an addition to the work of licensed physicians or psychologists, or it can be used in a stand-alone environment. Hypnotherapy is viewed as a helpful adjunct by proponents, having additive effects when treating psychological disorders along with scientifically proven cognitive therapies. Hypnosis has been used as a supplemental approach to cognitive behavioral therapy since as early as 1949. This includes inducing a relaxed state and then introducing a feared stimulus. One way of inducing the relaxed state is through hypnosis.[29]

Physicians and psychologists may use hypnosis to treat depression, anxiety, eating disorders, sleep disorders, compulsive gambling, phobias, and Posttraumatic stress disorder,[20] while certified hypnotherapists who are not physicians or psychologists often treat smoking and weight management. The effectiveness of hypnotherapy has not yet been accurately assessed. There is no evidence that 'incurable' diseases are curable with hypnosis (such as cancer, diabetes, and arthritis), but pain and other body functions related to the diseases are controllable.[30]

Hypnotherapy was historically used in psychiatric and legal settings to enhance the recall of repressed or degraded memories, but this application of the technique has declined as scientific evidence accumulated that hypnotherapy can increase confidence in false memories.[31] The American Medical Association and the American Psychological Association have both cautioned against the use of repressed memory therapy in dealing with cases of alleged childhood trauma:

At this point it is impossible, without other corroborative evidence, to distinguish a true memory from a false one.[32]

The use of recovered memories is fraught with problems of potential misapplication.[33]

The Council finds that recollections obtained during hypnosis can involve confabulations and pseudomemories and not only fail to be more accurate, but actually appear to be less reliable than nonhypnotic recall.[34]

Past life regression

Past life regression is a method that uses hypnosis to recover what practitioners believe are memories of past lives or incarnations. Past-life regression is typically undertaken either in pursuit of a spiritual experience, or in a psychotherapeutic setting. Most advocates loosely adhere to beliefs about reincarnation, though religious traditions that incorporate reincarnation generally do not include the idea of repressed memories of past lives.

The technique used during past-life regression involves the subject answering a series of questions while hypnotized to reveal identity and events of alleged past lives, a method similar to that used in recovered memory therapy and one that, similarly, often misrepresents memory as a faithful recording of previous events rather than a constructed set of recollections. The source of the memories is more likely cryptomnesia and confabulations that combine experiences, knowledge, imagination, and suggestion or guidance from the hypnotist than recall of a previous existence. Once created, those memories are indistinguishable from memories based on events that occurred during the subject's life.

The practice is widely considered discredited and unscientific by medical practitioners, and experts generally regard claims of recovered memories of past lives as fantasies or delusions or a type of confabulation. Experiments with subjects undergoing past-life regression indicate that a belief in reincarnation and suggestions by the hypnotist are the two most important factors regarding the contents of memories reported.[35]

Pain management

A number of studies show that hypnosis can reduce pain in patients suffering burns, dental surgery, and a variety of other painful conditions.[36] It may also be useful in decreasing a patient's fear about a medical procedure or treatment.

The American Psychological Association published a study comparing the effects of hypnosis, ordinary suggestion, and placebo in reducing pain. The study found that highly suggestible individuals experienced a greater reduction in pain from hypnosis compared with placebo, whereas less suggestible subjects experienced no pain reduction from hypnosis when compared with placebo. Ordinary non-hypnotic suggestion also caused reduction in pain compared to placebo, but was able to reduce pain in a wider range of subjects (both high and low suggestible) than hypnosis. The results showed that it is primarily the subject's responsiveness to suggestion, whether within the context of hypnosis or not, that is the main determinant of causing reduction in pain.[37]

Stage hypnosis

Stage hypnosis is a form of entertainment, traditionally employed in a club or theater before an audience. Stage hypnotists typically attempt to hypnotize the entire audience and then select individuals who are "under" to come up on stage and perform embarrassing acts, while the audience watches. However, the effects of stage hypnosis are probably due to a combination of psychological factors, participant selection, suggestibility, physical manipulation, stagecraft, and trickery.[38] The desire to be the center of attention, having an excuse to violate their own fear suppressors, and the pressure to please are thought to convince subjects to "play along."[39] Books by stage hypnotists sometimes explicitly describe the use of deception in their acts; for example, Ormond McGill's New Encyclopedia of Stage Hypnosis describes an entire "hypnosis" act that depends upon the use of private whispers throughout.[40]

Graham F. Wagstaff, of the University of Liverpool, carried out research around the phenomenon of stage hypnotism or hypnotism for entertainment. He surmised that rather than the subject being in an "altered state" they were affected significantly more by social factors and expectations.[39] Wagstaff's work explores how a hypnotist carefully chooses volunteers from the audience, puts them into a trance using hypnosis and then plants suggestions for them to perform. The critical factor in all stage hypnosis shows is the choice of enthusiastic and credulous individuals. Various techniques exist for discerning whether an individual is a likely candidate for a hypnosis stage act showing a higher than normal susceptibility. Often, the sheer willingness of audience members to volunteer is a sign that they will cooperate with the hypnotist's suggestions during the show, whether or not they ever really become hypnotized in the first place.[39]

Self-hypnosis

Self-hypnosis (or autosuggestion) is a staple of hypnotherapy-related self-help programs. This form of hypnosis involves a person hypnotizing himself or herself without the assistance of another person to serve as the hypnotist. It is most often used to help the self-hypnotist stay on a diet, overcome smoking or some other addiction, to reduce stress, or to generally boost the hypnotized person's self-esteem. Most people who practice self-hypnosis require a focus in order to become fully hypnotized; there are many computer programs on the market that can ostensibly help in this area, though few, if any, have been scientifically proven to aid self-hypnosis.

Based on their research program, Erika Fromm and her colleagues at the University of Chicago concluded that self-hypnosis promotes relaxation, relieves tension and anxiety, and reduces the level of physical pain and suffering without the necessity of having hypnotists present. Their approach, that has come to be known as the Chicago paradigm, promotes self-hypnosis as a tool for patients to take control over their pain:

Self-hypnosis permits the individual to be in charge and therefore helps the patient to get out of the role of the victim who suffers and into the role of the person who masters or attempts to master her pain. Through practicing self-hypnosis, patients can learn to isolate the feared pain that accompanies many a medical intervention; they can productively dissociate themselves into a position in which they can enjoy pleasurable fantasies and memories, away from the negative aspects of their current reality.[41]

Popular culture

For over a century, hypnosis has been a popular theme in fiction – literature, film, and television. It features in movies almost from their inception and more recently has been depicted in television and online media. The vast majority of these depictions are negative stereotypes of either control for criminal profit and murder or as a method of seduction. Others depict hypnosis as all-powerful or even a path to supernatural powers. [42]

Notes

- ↑ hypnosis Etymology Online. Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- ↑ Definition and Description of Hypnosis American Psychological Association Division 30. Retrieved October 22, 2022.

- ↑ Harriet Hall, Hypnosis Revisited Skeptical Inquirer, 45(2) (March/April 2021). Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 James Braid, Neurypnology; or, The Rationale of Nervous Sleep (Ayer Co Publisher, 1976 (original 1943), ISBN 0405074182).

- ↑ James Braid, The Power of the Mind over the Body: An Experimental Inquiry into the Nature and Cause of the Phenomena Attributed by Baron Reichenbach and Others to a "New Imponderable" Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal 66(169) (October 1, 1846): 286–312. Retrieved October 22, 2022.

- ↑ Donald Robertson, "On hypnotism" (1860) De l'hypnotisme Int J Clin Exp Hypn 57(2) (April 2009):133-161. Retrieved October 22, 2022.

- ↑ James Braid, Donald J. Robertson (ed.), The Discovery of Hypnosis: The Complete Writings of James Braid, the Father of Hypnotherapy (Lulu, 2013, ISBN 1304205150).

- ↑ Josef Breuer and Sigmund Freud, Studies on Hysteria (Basic Books, 2000, ISBN 978-0465082766).

- ↑ Sigmund Freud, "Lines of Advance in Psychoanalytic Therapy," in James Strachey (ed.), The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume 17 (1955), 157-168.

- ↑ Clark W. Hull, Hypnosis and Suggestibility (Crown House Publishing, 2002, ISBN 978-1899836932).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Andre M. Weitzenhoffer, The Practice of Hypnotism (John Wiley & Sons, 2000, ISBN 978-0471297901).

- ↑ Milton H. Erickson, Ernest L Rossi, and Sheila I. Rossi, Hypnotic Realities: The induction of clinical hypnosis and forms of indirect suggestion (Irvington Publishers, 1976, ISBN 978-0470151693).

- ↑ Joseph Wolpe, Psychotherapy by Reciprocal Inhibition (Stanford University Press, 1958, ISBN 978-0804705097).

- ↑ Albert Ellis, Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy (Citadel Press, 1962, ISBN 978-0806506012).

- ↑ Andre M. Weitzenhoffer and Ernest R. Hilgard, Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale (Leland Stanford University, 1959).

- ↑ Braid 1843, 27.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Theodore X. Barber, Nicholas P. Spanos, and John F. Chaves, Hypnosis, Imagination, and Human Potentialities (Pergamon Press, 1974, ISBN 978-0080179315).

- ↑ Hippolyte Bernheim, Hypnosis and Suggestion in Psychotherapy (Jason Aronson, 1993, ISBN 978-1568211381).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Andre M. Weitzenhoffer, Hypnotism: An Objective Study In Suggestibility (Literary Licensing, LLC, 2011, ISBN 978-1258168278).

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Deirdre Barrett, The Pregnant Man: Cases from a Hypnotherapist's Couch (Three Rivers Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0812929065).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Ernest L. Rossi and Kathryn L. Rossi, What is a Suggestion? The Neuroscience of Implicit Processing Heuristics in Therapeutic Hypnosis and Psychotherapy American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis 49(4) (April 2007): 267–281. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ↑ White, Robert W., A preface to the theory of hypnotism Journal of Abnormal Psychology 36(4) (October 1941): 477-505. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ↑ Clark Leonard Hull, Hypnosis and Suggestibility: An experimental approach (Crown House Publishing, 2002 (original 1933), ISBN 978-1899836932).

- ↑ Ivan P. Pavlov, Conditioned Reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex 1927. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ↑ Ivan P. Pavlov, Experimental Psychology (Philosophical Library, 1957).

- ↑ Michael Heap, Richard J. Brown, and David A. Oakley (eds.), The Highly Hypnotizable Person (Routledge, 2004, ISBN 978-1583911723).

- ↑ Gary E. Schwartz and David Shapiro (eds.), Consciousness and Self-Regulation: Advances in Research Volume 1 (Springer, 1976, ISBN 978-0306336010).

- ↑ Robert A. Baker, They Call It Hypnosis (Prometheus Books, 1990, ISBN 978-0879755768).

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Robin A. Chapman, The Clinical Use of Hypnosis in Cognitive Behavior Therapy: A Practitioner's Casebook (Springer Publishing Company, 2005, ISBN 978-0826128843).

- ↑ Andrew Vickers and Catherine Zollman, Hypnosis and relaxation therapies BMJ 319(7221) (November 20, 1999): 1346–1349. Retrieved October 25, 2022.

- ↑ gSteven Jay Lynn, Irving Kirsch, Devin B. Terhune, and Joseph P. Green, Myths and misconceptions about hypnosis and suggestion: Separating fact and fiction Applied Cognitive Psychology 34(6) (November/December, 2020): 1253-1264. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ↑ American Psychological Association, Questions and Answers about Memories of Childhood Abuse Memories of Childhood Abuse, 1995. Retrieved October 25, 2022.

- ↑ American Medical Association, Council on Scientific Affairs, Report on memories of childhood abuse Int J Clin Exp Hypn 43(2) (April 1995):114-117. Retrieved October 25, 2022.

- ↑ American Medical Association, Council on Scientific Affairs, Scientific Status of Refreshing Recollections by the Use of Hypnosis JAMA 253(13) (April 5, 1985): 1918-1923. Retrieved October 25, 2022.

- ↑ Nicholas P. Spanos, Multiple Identities and False Memories: A Sociocognitive Perspective (American Psychological Association, 1996, ISBN 978-1557988935).

- ↑ Michael R. Nash, The Truth and the Hype of Hypnosis Scientific American, July 1, 2001. Retrieved October 25, 2022.

- ↑ Nicholas P. Spanos, Arthur H. Perlini, and Lynda A. Robertson, Hypnosis, suggestion, and placebo in the reduction of experimental pain Journal of Abnormal Psychology (1989). Retrieved October 25, 2022.

- ↑ Michael D. Yapko, Trancework: An Introduction to the Practice of Clinical Hypnosis (Routledge, 2018, ISBN 978-1138563100).

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Graham F. Wagstaff, Hypnosis, Compliance and Belief (St. Martin's Press, 1981, ISBN 978-0312401573).

- ↑ Ormond McGill, The New Encyclopedia of Stage Hypnotism (Crown House Publishing, 1996, ISBN 1899836020).

- ↑ Erika Fromm and Stephen Khan, Self-Hypnosis: The Chicago Paradigm (The Guilford Press, 1990, ISBN 978-0898623413).

- ↑ Deirdre Barrett (ed.), Hypnosis and Hypnotherapy (Praeger, 2010, ISBN 978-0313356322).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baker, Robert A. They Call It Hypnosis. Prometheus Books, 1990. ISBN 978-0879755768

- Barber, Theodore X., Nicholas P. Spanos, and John F. Chaves. Hypnosis, Imagination, and Human Potentialities. Pergamon Press, 1974. ISBN 978-0080179315

- Barrett, Deirdre. The Pregnant Man: Cases from a Hypnotherapist's Couch. Three Rivers Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0812929065

- Barrett, Deirdre (ed.). Hypnosis and Hypnotherapy. Praeger, 2010. ISBN 978-0313356322

- Bernheim, Hippolyte. Hypnosis and Suggestion in Psychotherapy. Jason Aronson, 1993. ISBN 978-1568211381

- Braid, James. Neurypnology; or, The Rationale of Nervous Sleep. Ayer Co Publisher, 1976 (original 1843). ISBN 0405074182

- Braid, James. Donald J. Robertson (ed.). The Discovery of Hypnosis: The Complete Writings of James Braid, the Father of Hypnotherapy. Lulu, 2013. ISBN 1304205150

- Breuer, Josef, and Sigmund Freud. Studies on Hysteria. (Basic Books, 2000 (original 1895). ISBN 978-0465082766

- Chapman, Robin A. The Clinical Use of Hypnosis in Cognitive Behavior Therapy: A Practitioner's Casebook. Springer Publishing Company, 2005. ISBN 978-0826128843

- Ellis, Albert. Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy. Citadel Press, 1962., ISBN 978-0806506012

- Erickson, Milton H., Ernest L Rossi, and Sheila I. Rossi. Hypnotic Realities: The induction of clinical hypnosis and forms of indirect suggestion. Irvington Publishers, 1976., ISBN 978-0470151693

- Forrest, Derek. Hypnotism: A History. Penguin Books, 2001. ISBN 978-0140280401

- Fromm, Erika, and Stephen Khan. Self-Hypnosis: The Chicago Paradigm. The Guilford Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0898623413

- Heap, Michael, Richard J. Brown, and David A. Oakley (eds.). The Highly Hypnotizable Person. Routledge, 2004. ISBN 978-1583911723

- Hughes, John C. The Illustrated History of Hypnotism. National Guild of Hypnotists, Inc., 2008. ISBN 978-1885846143

- Hull, Clark W. Hypnosis and Suggestibility. Crown House Publishing, 2002 (original 1933). ISBN 978-1899836932

- McGill, Ormond. The New Encyclopedia of Stage Hypnotism. Crown House Publishing, 1996. ISBN 1899836020

- Pavlov, Ivan P. Experimental Psychology. Philosophical Library, 1957. ASIN B0006AUVIK

- Schwartz, Gary E., and David Shapiro (eds.). Consciousness and Self-Regulation: Advances in Research Volume 1. Springer, 1976. ISBN 978-0306336010

- Spanos, Nicholas P. Multiple Identities and False Memories: A Sociocognitive Perspective. American Psychological Association, 1996. ISBN 978-1557988935

- Strachey, James (ed.). The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume 17. 1955.

- Wagstaff, Graham F. Hypnosis, Compliance and Belief. St. Martin's Press, 1981. ISBN 978-0312401573

- Weitzenhoffer, Andre M. The Practice of Hypnotism. John Wiley & Sons, 2000. ISBN 978-0471297901

- Weitzenhoffer, Andre M. Hypnotism: An Objective Study In Suggestibility. Literary Licensing, LLC, 2011. ISBN 978-1258168278

- Weitzenhoffer Andre M., and Ernest R. Hilgard. Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale. Leland Stanford University, 1959.

- Wolpe, Joseph. Psychotherapy by Reciprocal Inhibition. Stanford University Press, 1958. ISBN 978-0804705097

- Yapko, Michael D. Trancework: An Introduction to the Practice of Clinical Hypnosis. Routledge, 2018. ISBN 978-1138563100

External links

All links retrieved October 26, 2022.

- Hypnosis And Suggestion

- How Hypnosis Works How Stuff Works

- The National Council for Hypnotherapy (UK)

- National Guild of Hypnotists (USA)

- International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

_-_Nationalmuseum_-_18855.jpg/400px-Hypnotic_Séance_(Richard_Bergh)_-_Nationalmuseum_-_18855.jpg)