Iceland

| Lýðveldið Ísland Republic of Iceland |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: Lofsöngur "Hymn" |

||||||

| Location of Iceland (dark orange)

at the European continent (clear) |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Reykjavík 64°08′N 21°56′W | |||||

| Official languages | Icelandic | |||||

| Ethnic groups | 93% Icelandic, ~2.0% Scandinavian[1] ~5.0% other (see demographics) |

|||||

| Demonym | Icelander, Icelandic | |||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic | |||||

| - | President | Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir | ||||

| - | Speaker of the Alþingi | Ásta Ragnheiður Jóhannesdóttir | ||||

| Legislature | Alþingi | |||||

| Establishment—Independence | ||||||

| - | Settlement | 9th century | ||||

| - | Commonwealth | 930–1262 | ||||

| - | Union with Norway | 1262–1814 | ||||

| - | Danish monarchy | 1380–1944 | ||||

| - | Constitution | 5 January 1874 | ||||

| - | Kingdom of Iceland | 1 December 1918 | ||||

| - | Republic | 17 June 1944 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 103,001 km² (108th) 39,770 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 2.7 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 1 January 2011 estimate | 318,452[2] (175th) | ||||

| - | Density | 3.1/km² (232nd) 7.5/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2010 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $11.818 billion[3] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $36,620[3] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2010 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $12.594 billion[3] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $39,025[3] | ||||

| Gini (2010) | 25.0[4] (low) (1st) | |||||

| Currency | Icelandic króna (ISK) |

|||||

| Time zone | GMT (UTC+0) | |||||

| Internet TLD | .is | |||||

| Calling code | [[+354]] | |||||

Iceland, officially the Republic of Iceland, is a country of northwestern Europe, comprising the island of Iceland and its outlying islets in the North Atlantic Ocean between Greenland, Norway, the British Isles, and the Faroe Islands. Its capital and largest city is Reykjavík.

Iceland has been inhabited since about the year 874 when, according to Landnámabók, the Norwegian chieftain Ingólfur Arnarson became the first permanent Norwegian settler on the island. Others had visited the island earlier and stayed over winter. Over the next centuries, people of Nordic and Gaelic origin settled in Iceland. Until the twentieth century, the Icelandic population relied on fisheries and agriculture, and was from 1262 to 1944 a part of the Norwegian and later the Danish monarchies.

Today, Iceland is a highly developed country, the world's fifth and second in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and human development respectively. Iceland is a member of the United Nations, North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), European Economic Area (EEA), and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Geography

Iceland is located in the North Atlantic Ocean just south of the Arctic Circle, 178 miles (287 km) from Greenland, 496 miles (798 km) from the United Kingdom, and 603 miles (970 km) from Norway. The small island of Grímsey, off Iceland's northern coast, lies atop the Arctic Circle. Unlike neighboring Greenland, Iceland is considered to be a part of Europe, not of North America, though geologically, the island belongs to both continents. Because of cultural, economic, and linguistic similarities, Iceland is sometimes considered part of Scandinavia. At 39,768 square miles (103,000 km²), it is the world's eighteenth largest island, and Europe's second largest island following Great Britain.

Approximately eleven percent of the island is glaciated (4,603 mi² or 11,922 km²). [5] Many fjords punctuate its 3,088 mile (4,970 kilometer) long coastline. Most towns are situated along the coast because the island's interior, the Highlands, is a cold and uninhabitable region of sands and mountains. The major urban areas are the capital Reykjavík, Keflavík, where the international airport is located, and Akureyri. The island of Grímsey on the Arctic Circle contains the northernmost habitation of Iceland.[6]

Iceland is unusually suited for waterfalls. Having a north Atlantic climate that produces frequent rain or snow and a near-Arctic location that produces large glaciers, whose summer melts feed many rivers. As a result, it is home to a number of large and powerful waterfalls.

Geology

Iceland is situated on a geological hot spot, thought to be caused by a mantle plume, and the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. This combination means that the island is extremely geologically active. It has 130 volcanic mountains, of which 18 have erupted since its settlement. Its most notable volvanoes are Hekla, Eldgjá, and Eldfell. The volcanic eruption of Laki in 1783-1784 caused a famine that killed nearly a quarter of the island's population; the eruption caused dust clouds and haze to appear over most of Europe and parts of Asia and Africa for several months after the eruption.

There are also geysers (the word is derived from the name of a geyser in Iceland, Geysir). With this widespread availability of geothermal power, and also because of the numerous rivers and waterfalls that are harnessed for hydropower, residents of most towns have natural hot water and heat in their houses.

The island itself is composed primarily of basalt, a low-silica lava associated with effusive volcanism like Hawaii. There are, however, a variety of volcano types on Iceland that produce other, more evolved lavas like rhyolite and andesite. Iceland controls Surtsey, one of the youngest islands in the world, which rose above the ocean in a series of volcanic eruptions between November 8, 1963 and June 5, 1968.

Climate

The climate of Iceland is temperate-cold oceanic. The warm North Atlantic Current ensures generally higher temperatures than in most places of similar latitude in the world. The winters are mild and windy while the summers are damp and cool. Regions in the world with similar climate are the Aleutian Islands, the Alaska Peninsula, and Tierra del Fuego.

There are some variations in the climate between different parts of the island. Very generally speaking, the south coast is warmer, wetter and windier than the north. Low lying inland areas in the north are the most arid. Snowfall in winters is more common in the north than the south. The Central Highlands are the coldest part of the country. Average temperature in the warmest months range from highs of 55° to 57° F (13° to 14° C) and averages lows of around 45° F (7° C). In the coldest months, the high temperatures average around 33° F (1°C) and the average lows from 23° to 26° F (-5° to -3° C).

The highest air temperature recorded was 86.9°F (30.5°C) on June 22, 1939, at Teigarhorn on the southeastern coast. The lowest temperature was -36.4°F (-38°C) on January 22, 1918 at Grímsstaðir and Möðrudalur in the interior of northeast. The temperature records for Reykjavík are 76.6°F (24.8°C) on August 11, 2004, and -12.1°F (-24.5°C) on January 21, 1918. Rainfall varies regionally, with areas along the southern coast averaging 118 inches (3000mm) annually, and the drier interior averaging around 16 inches (400 mm) annually.

Flora and fauna

The only native land mammal when humans arrived was the arctic fox. It came to the island at the end of the ice age, walking over the frozen sea. There are no native reptiles or amphibians on the island. There are around 1,300 known species of insects in Iceland, which is rather low compared with other countries (there are about 925,000 known species in the world). During the last Ice Age almost all of the country was covered by permanent snow and glacier ice, the likely explanation for the low number of living species in Iceland.

When humans arrived, birch forest and woodland probably covered 25-40 percent of Iceland’s land area. Settlers started to remove the trees and forests to create fields and grazing land. By the early twentieth century, the forests were nearly depleted. Reforestation efforts have been gradually restoring the forests, but not to the extent of the original tree cover. Some of these new forests have included new foreign species.

Iceland has four national parks: Jökulsárgljúfur National Park, Skaftafell National Park, Snæfellsjökull National Park, and Þingvellir National Park.

Resources

Iceland has very few mineral or agricultural resources. Approximately three-quarters of the island is barren of vegetation, and plant life consists mainly of grassland which is regularly grazed by livestock. The only native tree in Iceland is the northern birch Betula pubescens, whose forests were devastated over the centuries for firewood and building supplies. Deforestation then resulted in a loss of critical top soil due to erosion, greatly reducing the ability for the birches to regrow. Today, only a few small birch stands can only be found in isolated drainages. The animals of Iceland are mainly agricultural and include Icelandic sheep, cattle, and the sturdy Icelandic horse. Many varieties of fish live in the ocean waters surrounding Iceland, and the fishing industry is a main contributor to Iceland’s economy, accounting for more than half of Iceland’s total exports.

History

Early settlement

The first people said to have inhabited Iceland were Irish monks, who probably settled there in the eight century. There is, however, no archaeological evidence of any settlement by the Irish, and only a few passages in books offer documentary evidence of their residence in Iceland. They are said to have left the country on the arrival of the pagan Norsemen.

The main source of information about the settlement period in Iceland is the Book of Settlements (Landnámabák), written in the twelfth century, which gives a detailed account of the first settlers. According to this book, Scandinavian sailors accidentally discovered the country. A few voyages of exploration were made soon after that and then the settlement started. Ingólfur Arnarson was said to be the first settler. He was a chieftain from Norway, arriving in Iceland with his family and dependents in 874. During the next 60 years or so, Viking settlers from Scandinavia and also from Norse colonies in the British Isles - Ireland, Scotland and the Scottish Isles - settled in the country. [7]

The Althing, Iceland's legislative assembly and court, dates from this era (930 C.E.), making it the oldest functioning assembly in the world. Iceland maintained its independence for the next 300 years, an era also marked by exploration and attempts at settling in what became North America.

Foreign rule

By the middle 1200s, Iceland came under the rule of Norway. The two countries had long been closely allied; Norse mythology and even the language were enshrined in the legendary Icelandic sagas that marked the times.

After the formation of the Kalmar Union, Denmark took control of Iceland. Restrictive trade agreements were instituted between Iceland and Denmark; aggravated by agricultural and natural disasters, resultant famines, and epidemics, the effects of Danish control resulted in misery for the Icelandic people. Denmark's rule continued, but trade and other restrictions were modified over three centuries until home rule was finally established in 1904. The two countries still shared a ruler, and special trade agreements with Denmark still held for 40 more years until Iceland became a full Republic in 1944.

Modern times

Iceland was initially a neutral state during the Second World War. In 1940 it was occupied by British forces and in 1941, by invitation from the Icelandic Government, U.S. troops replaced the British.

In 1949, Iceland became a founding Member of NATO. It also joined a Bilateral Defense Agreement with the U.S. in 1951, which remains in effect. Icelend has engaged in several disputes with the United Kingdom over expansion of national fishing limits since the 1950s, which have been known as the "cod wars."

Iceland joined the United Nations in 1946 and is a founding member of the OECD (then OEEC), the EFTA, and the EEA, as well as subscribing to the GATT. [8]

Government and politics

Iceland's modern parliament, called "Alþingi" (English: Althing), was founded in 1845 as an advisory body to the Danish king. It was widely seen as a reestablishment of the assembly founded in 930 in the Commonwealth period and suspended in 1799. It currently has 63 members, each of whom is elected by the population every four years.

The President of Iceland is a largely ceremonial office that serves as a diplomat and head of state. The head of government is the prime minister, who, together with the cabinet, forms the executive branch of government. The cabinet is appointed by the president after general elections to Althing. This process is usually conducted by the leaders of the political parties, who decide among themselves after discussions which parties can form the cabinet and how its seats are to be distributed (under the condition that it has a majority support in Althing). Only when the party leaders are unable to reach a conclusion by themselves in reasonable time does the president exercise the power to appoint the cabinet him or herself. This has not happened since the republic was founded in 1944, but in 1942, the regent of the country, Sveinn Björnsson, who had been installed in that position by the Althing in 1941 did appoint a non-parliamentary government. The regent had, for all practical purposes, the powers of a president, and Björnsson in fact became the country's first president in 1944.

The governments of Iceland have almost always been coalitions with two or more parties involved, due to the fact that no single political party has received a majority of seats in Althing in the republic period. The extent of the political powers inheriting the office of the president are disputed by legal scholars in Iceland; several provisions of the constitution appear to give the president some important powers but other provisions and traditions suggest differently.

Iceland elected the first female president ever, Vigdís Finnbogadóttir in 1980; she retired from office in 1996. Elections for the office of presidency, parliament, and in town councils are all held every four years, staggered. Elections were last held in 2004 (presidency), 2003 (parliament) and 2006 (town councils), respectively.

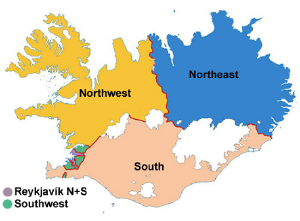

Administrative Divisions

Iceland is divided into eight regions, six constituencies (for voting purposes), 23 counties, and 79 municipalities. The eight regions are primarily used for statistical purposes; the district court jurisdictions also use an older version of this division. Until 2003, the constituencies, political divisions created for parliamentary elections, were the same as the regions, but by an amendment to the constitution, they were changed to the current six constituencies:

- Reykjavík North and Reykjavík South (city regions);

- Southwest (three suburb areas around Reykjavík);

- Northwest and Northeast (north half of Iceland, split); and,

- South (south half of Iceland, excluding Reykjavík and suburbs).

The redistricting change was made in order to balance the weight of different districts of the country, since a vote cast in the sparsely populated areas around the country would count much more than a vote cast in the Reykjavík city area. The new system reduces that imbalance but does not eliminate it.[6]

Iceland's 23 counties are largely historical divisions. Currently, Iceland is split up among 26 magistrates that represent government in various capacities. Among their duties are running the local police (except in Reykjavík, where there is a special office of police commissioner), tax collection, administering bankruptcy declarations, and performing civil marriages. There are 79 municipalities in Iceland that govern most local matters like schools, transportation and zoning.[6]

Military

Iceland, a NATO member, has not had a standing army since the nineteenth century, although it has an expeditionary military peacekeeping unit known as the Icelandic Crisis Response Unit or Íslenska Friðargæslan.

Iceland has a Coast Guard (Landhelgisgæslan) which operates armed Offshore Patrol Vessels and aircraft, and a counter-terrorism team named Sérsveit Ríkislögreglustjóra (English: "The Special Operations Task Force of the National Commissioner of the Icelandic Police"), commonly referred to as Víkingasveitin (The Viking Team or Viking Squad) similar to the German GSG 9. The Icelandic National Police consists of over 700 officers; unpaid volunteer Rescue and Civil Defence Units have more than 4,000 active members and 18,000 registered members overall.

From 1951 until 2006, Military Defenses were provided by a (predominantly U.S.) Defense force in the NATO base on Miðnesheiði near Keflavík. [9] This base is now in the hands of the Sheriff of Keflavík Airport. An Air Defense radar network, known as the Iceland Air Defense System (IADS) or Íslenska Loftvarnarkerfið is operated by Ratsjárstofnun.

Economy

.png)

The Ring Road of Iceland and some towns it passes through.

1.Reykjavík, 2.Borgarnes, 3.Blönduós, 4.Akureyri,

The economy of Iceland is small but well-developed, with a gross domestic product estimated at US$10.57 billion in 2005 (and a per capita GDP of $35,600, which is among the world's highest.)[6]

Like the other Nordic countries, Iceland has a mixed economy that is mainly capitalistic but supports an extensive welfare state. Social expenditure is, however, below that of mainland Scandinavia and most of western Europe.

Iceland is the fifth most productive country in the world based on GDP per capita at purchasing power parity. It is also ranked second on the 2005 United Nations Human Development Index. The economy historically depended heavily on the fishing industry, which still provides almost 40 percent of export earnings and employs 8 percent of the work force. Without other natural resources (except for abundant hydro-electric power and geothermal power), Iceland's economy is vulnerable to changing world fish prices. The economy is also sensitive to declining fish stocks as well as to drops in world prices for its other main material exports including aluminium, and ferrosilicon. Although the Icelandic economy still relies heavily on fishing, the travel industry, technology, energy intensive, and various other industries are growing in importance.

The center-right government follows economic policies of reducing the budget and current account deficits, limiting foreign borrowing, containing inflation, revising agricultural and fishing policies, diversifying the economy, and privatizing state-owned industries. The government remains opposed to European Union membership, primarily because of Icelanders' concern about losing control over their fishing resources.

Iceland's economy has been diversifying into manufacturing and service industries in the last decade, and new developments in computer software production, biotechnology, and financial services are occurring. The tourism sector is also expanding, with the recent trends in ecotourism and whale-watching. Growth slowed between 2000 and 2002, but the economy expanded by 4.3 percent in 2003 and grew by 6.2 percent in 2004. The unemployment rate of 1.8 percent (third quarter of 2005) is among the lowest in the European Economic Area.

Over 99 percent of the country's electricity is produced from hydropower and geothermal energy.

Iceland's agriculture industry consists mainly of potatoes, turnips, green vegetables (in greenhouses), mutton, dairy products and fish.[6] Some are examining the possibility of introducing other crops from South America, where the potato is native. Given that summers in Iceland are not hot enough to produce some other types of food, those plants that are from the same ecological range as the potato (those from a similar climate to Iceland), may very probably be adaptable to Iceland. Those of interest include the quinoa, a pseudocereal; beach strawberry ; calafate, a fruit; and the Monkey-puzzle araucaria, a tree that produces edible nuts. Those crops would help the country to reduce imports of food like cereals, fruits, and nuts.

Iceland's stock market, the Iceland Stock Exchange (ISE), was established in 1985.

Demographics

The original population of Iceland was of Nordic and Celtic origin. This is surmised from literary evidence of the settlement period as well as from later scientific studies such as blood type and genetic analysis. One such genetics study has indicated that the majority of the male settlers were of Nordic origin while the majority of the women were of Celtic origin.[10]

The modern population of Iceland is often described as a "homogeneous mixture of descendants of Norse and Celts" but some history scholars reject the alleged homogeneity as a myth that fails to take into account that Iceland was never completely isolated from the rest of Europe and has had contact with traders and fishermen from many groups and nationalities through the ages.

Iceland has extensive genealogical records about its population dating back to the age of settlement. Although the accuracy of these records is debated, they are regarded as valuable tools for conducting research on genetic diseases.

The population of the island is believed to have varied from 40,000 to 60,000 from its initial settlement until the mid-nineteenth century. During that time, cold winters, ashfall from volcanic eruptions, and plagues decreased the population several times. The population of the island was 50,358 when the first census was carried out in 1703. Improving living conditions triggered a rapid increase in population from the mid-nineteenth century to the present day - from about 60,000 in 1850 to 300,000 in 2006.

In December 2007, 33,678 people (13.5 percent of the total population) living in Iceland had been born abroad, including children of Icelandic parents living abroad. 19,000 people (6 percent of the population) held foreign citizenship. Polish people make up the far largest minority nationality, and still form the bulk of the foreign workforce. About 8,000 Poles now live in Iceland, 1,500 of them in Reyðarfjörður where they make up 75 percent of the workforce who are building the Fjarðarál aluminium plant.[11] The recent surge in immigration has been credited to a labor shortage because of the booming economy at the time, while restrictions on the movement of people from the Eastern European countries that joined the EU / European Economic Area in 2004 have been lifted. Large-scale construction projects in the east of Iceland (see Kárahnjúkar Hydropower Project) have also brought in many people whose stay is expected to be temporary. Many Polish immigrants were also considering leaving in 2008 as a result of the Icelandic financial crisis.[12]

The island's spoken language is Icelandic, a North Germanic language. In terms of etymology, the Icelandic language is the closest to Old Norse, the language of the Vikings. Today, the closest language still in existence to Icelandic is Faroese. In education, the use of Icelandic Sign Language for the Deaf in Iceland is regulated by the National Curriculum Guide.

Prominent foreign languages include English, Danish, other Scandinavian languages, and German.

The southwest corner of Iceland is the country's most densely populated region. Reykjavík, the northernmost capital in the world, is located there. The largest towns outside the capital region are Akureyri and Reykjanesbær.

Religion

Icelanders enjoy freedom of religion as stated by the constitution; however, church and state are not separated and the National Church of Iceland, a Lutheran body, is the state church. The national registry keeps account of the religious affiliation of every Icelandic citizen and according to it, Icelanders in 2005 divided into religious groups as follows:

- 84.1 percent members of the National Church of Iceland.

- 4.6 percent members of the Free Lutheran Churches of Reykjavík and Hafnarfjörður.

- 2.5 percent not members of any religious group.

- 2.2 percent members of the Roman Catholic Church, which has a Diocese of Reykjavík.

The remaining 6.6 percent are mostly divided among 20-25 other Christian denominations and sects, with less than 1 percent of the population in non-Christian religious organizations including a tiny group of state-sanctioned indigenous Ásatrú adherents in the Íslenska Ásatrúarfélagið.[6]

Most Icelanders are either very liberal in their religious beliefs or uninterested in religious matters altogether, and do not attend church regularly.

Society and culture

Icelanders place a great deal of importance on their Nordic heritage; independence and self reliance are valued as outgrowths of that heritage. They remain proud of their Viking heritage and Icelandic language. Modern Icelandic remains close to the Old Norse spoken in the Viking Age.

Icelandic society has a high degree of gender equality, with many women in leadership positions in government and business. Women retain their names after marriage, since Icelanders generally do not use surnames but patronyms or (in certain cases) matronyms.

Iceland's literacy rate is among the highest in the world, and the nation is well–known for its literary heritage which stems from authors from the twelfth to fourteenth centuries.

Sports and leisure

Though changing in the past years, Icelanders remain a very healthy nation. Children and teenagers participate in various types of sports and leisure activities. Popular sports today are mainly soccer, track and field and basketball. Sports such as golf, tennis, swimming, chess and horseback riding are also popular.

Chess is a popular type of recreation favored by the Icelanders Viking ancestors. The country's chess clubs have created many chess grandmasters including Friðrik Ólafsson, Jóhann Hjartarson, Margeir Pétursson, and Jón Arnason.

Glima is a form of wrestling that is still played in Iceland, though originating with the Vikings. Swimming and horseback riding are popular as well. Golf is an especially common sport, with about one-eighth of the nation playing. [13]

Team handball is often referred to as a national sport with Iceland's team one of the top ranked teams in the world. Icelandic women are surprisingly good at soccer compared to the size of the country; the national team ranked the eighteenth best by FIFA.

Ice and rock climbing are a favorite among many Icelanders, for example to climb the top of the 4,167-foot (1,270 metre) Thumall peak in Skaftafell National Park is a challenge for many adventurous climbers, but mountain climbing is considered to be more suitable for the general public and is a very common type of leisure activity. The Hvítá, among many other of the Icelandic glacial rivers, attracts kayakers and river rafters worldwide.

Among the most popular tourist attractions in Iceland are the geothermal spas and pools that can be found all around the country, such as Bláa Lónið (The Blue Lagoon) on the Reykjanes Peninsula.

Arts

The Reykjavík area has several professional theatres, a symphony orchestra, an opera, and a large amount of art galleries, bookstores, cinemas, and museums.

The people of Iceland are famous for their prose and poetry and have produced many great authors including Halldór Laxness (winner of the Nobel Prize for literature in 1955), Guðmundur Kamban, Tómas Guðmundsson, Davíð Stefánsson, Jón Thoroddsen, Guðmundur G. Hagalín, Þórbergur Þórðarson and Jóhannes úr Kötlum.

Iceland's best-known classical works of literature are the Icelanders' sagas, prose epics set in Iceland's age of settlement. The most famous of these include Njáls saga, about an epic blood feud, and Grœnlendinga saga and Saga of Eric the Red, describing the discovery and settlement of Greenland and Vinland (modern Newfoundland). Egil's saga, Laxdaela saga, Grettis saga, Gísla saga and Gunnlaugs saga are also notable and popular Icelanders' sagas.

W. H. Auden and Louis MacNeice wrote Letters From Iceland (1937) to describe their travels through that country.

The first professional secular painters appeared in Iceland in the nineteenth century. This group of artists included Johannes Sveinsson Kjarval who was famous for his paintings portraying village life in Iceland. Asmundur Sveinsson, a twentieth century sculptor, was also from Iceland.

Cuisine

Iceland offers wide varieties of traditional cuisine. Þorramatur (food of the þorri) is the Icelandic national food. Nowadays þorramatur is mostly eaten during the ancient Nordic month of þorri, in January and February, as a tribute to old culture. Þorramatur consists of many different types of food. These are mostly offal dishes like pickled rams' testicles, putrified shark meat, singed sheep heads, singed sheep head jam, blood pudding, liver sausage (similar to Scottish haggis) and dried fish (often cod or haddock) with butter.

Technology

Iceland is one of the world's most technologically advanced and digitally-connected countries. It has the highest number of broadband Internet connections per capita among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. [14]

Notes

- ↑ Statistics Iceland, Population by origin and citizenship Retrieved December 19, 2011.

- ↑ Statistics Iceland, Key figures. Retrieved December 19, 2011.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 International Monetary Fund.

- ↑ Error on call to template:cite web: Parameters url and title must be specified. Central Intelligence Agency.

- ↑ Ólafur Ingólfsson, Icelandic glaciers, Ólafur Ingólfsson, Professor of glacial and Quaternary Geology. Retrieved April 7, 2007.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Central Intelligence Agency, Iceland, The World Factbook. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- ↑ History, Iceland.org. Retrieved April 7, 2007.

- ↑ History, www.iceland.is. Retrieved April 7, 2007.

- ↑ Jim Garamone, September 29, 2006. Last U.S. Service Members to Leave Iceland Sept. 30, Navy Newsstand. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

- ↑ Agnar Helgason, et al. 2000. Estimating Scandinavian and Gaelic Ancestry in the Male Settlers of Iceland. American Journal of Human Genetics (Institute of Biological Anthropology, University of Oxford.) Retrieved April 9, 2007.

- ↑ Lowana Veal, Iceland: Migration Appears Here Too IPS.

- ↑ "Iceland faces immigrant exodus", BBC News, 2008-10-21. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- ↑ Golf, Golf.is.

- ↑ April 13, 2006, Iceland comes first in broadband, BBC News Online. Retrieved April 9, 2007.

References and further reading

- Byock, Jesse L. Viking Age Iceland. London: Penguin Books, 2001. ISBN 9780140291155

- Karlsson, Gunnar. The history of Iceland. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2000. ISBN 0816635889

- Somervill, Barbara A. Iceland. (Enchantment of the world) New York, NY: Children's Press, 2003. ISBN 0516226940

- Wilcox, Jonathan. Iceland. (Cultures of the world.) New York, NY: M. Cavendish,1996. ISBN 0761402799

External links

All links retrieved January 25, 2018.

- The Official Gateway to Iceland. iceland.is.

- History of Iceland: Primary Documents. Euro Docs.

- Iceland to begin whalemeat trade. British Broadcasting Corporation News.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Iceland history

- Economy_of_Iceland history

- Demographics_of_Iceland history

- Culture_of_Iceland history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.