Ichneumonidae

| Ichneumon wasps | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Unidentified species, Rhône (France)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

see below |

Ichneumonidae is a diverse family of wasps, typically characterized by a parasitic component to the life cycle, antennae with 16 or more segments, an elongated abdomen, and females with long ovipositors that frequently are longer than their body. This family is within the Aporcrita suborder of the Hymenoptera order, a taxon that also includes ants, bees, and sawflies. Members of Ichneumonidae commonly are called ichneumon wasps. Less exact terms are ichneumon flies (they are not closely related to true flies), or scorpion wasps due to the extreme lengthening and curving of the abdomen (scorpions are not insects). Simply but ambiguously, these insects are commonly called "ichneumons," which is also a term for the Egyptian mongoose (Herpestes ichneumon); ichneumonids is often encountered as a less ambiguous alternative.

Ichneumonidae has a cosmopolitan distribution, with over 60,000 species worldwide. There are approximately 3,000 species of ichneumonids in North America. The distribution of Ichneumonidae is one of the most notable exceptions to the common latitudinal gradient in species diversity because it shows greater speciation at high latitudes than at low latitudes (Sime and Brower 1998).

Ichneumon wasps are important parasitoids of other insects. Common hosts are larvae and pupae of Coleoptera, Hymenoptera, and Lepidoptera.

For Charles Darwin, the life cycle of parasitic Ichneumonidae presented a religious conundrum: How could a just and benevolent God create a living being that deposited its eggs inside a caterpillar, such that the emerging wasp larvae would eat first the digestive organs, keeping the twitching caterpillar alive until the larva got to the more immediately vital organs? The mechanism of natural selection as the directive or creative force—a materialistic, purposeless, and non-progressive agent—resolves such a philosophical issue. However, one may also note that the parasitic wasp, as with other taxa, are part of an extraordinary harmony in nature, which appears to be underlain by the principle of bi-level functionality. This principle notes that taxonomic groups not only advance their own individual functions (survival, reproduction, development), but also provide a larger function (for the ecosystem, humans). In the case of the caterpillar being consumed by wasp larva, it provides food for the parasitic wasp. In the case of the parasitic wasps, they play an essential role in the function of ecosystems as part of food chains, as predator and prey, and in the control of insects. For humans, Ichneumonidae offer a natural biocontrol of pest insects, such as those that eat agricultural crops.

Overview

As members of the Hymenoptera suborder Apocrita, along with bees, ants, and other wasps, ichneumonids are characterized by a constriction between the first and second abdominal segments called a wasp-waist. This also involves the fusion of the first abdominal segment to the thorax. Ichneumonids are holometabolus insects, meaning they undergo complete metamorphosis in which the larvae differ markedly from the adults. The larva of ichneumonids, like all Apocrita, do not have legs, prolegs, or ocelli. As in other Hymenoptera, sexes are significantly genetically different. Females have a diploid (2n) number of chromosomes and come about from fertilized eggs. Males, in contrast, have a haploid (n) number of chromosomes and develop from an unfertilized egg.

Ichneumonids belong to the Apocrita division Parasitica, which includes the superfamilies Ichneumonoidea, Chalcidoidea, Cynipoidea, and Proctotrupoidea (Grzimek et al. 2004). Members of the Parasitica tend to be parasites on other insects, while membes of the other division of Apocrita, Aculeata, which contains ants, bees, and others wasps, tend to be stinging forms. In Aculeata, the ovipositor (an organ typically used for laying eggs) is adapted into a venomous stinger. (Some Parasitca are phytophagous and many Aculeata are parasites (Grzimek et al. 2004).

Ichneumon wasps differ from the wasps that sting in defense (Aculeata: Vespoidea and Apoidea) in that the antennae have more segments; typically 16 or more, whereas the others have 13 or fewer. Their abdomen is characteristically very elongated, unlike in their relatives the braconids. This lengthened section may also be segmented. Female ichneumon wasps frequently exhibit an ovipositor longer than their body. Ovipositors and stingers are homologous structures; some Ichneumons inject venom along with the egg, but they do not use the ovipositor as a stinger, per se, except in the subfamily Ophioninae. Stingers in aculeate Hymenoptera—which like Ichneumonidae belong to the Apocrita—are used exclusively for defense; they cannot be used as egg-laying equipment. Males do not possess stingers or ovipositors in either lineage.

Oviposition

Some species of ichneumon wasps lay their eggs in the ground, but most inject them directly into a host's body, typically into a larva or pupa. Host information has been notably summed up by Aubert (1969, 1978, 2000), Perkins (1959, 1960), and Townes et al. (1965).

In some of the largest species, namely from the genera Megarhyssa and Rhyssa, both sexes will wander over the surface of logs, and tree trunks, tapping with their antennae. Each sex does so for a different reason; females are "listening" for wood boring larvae of the horntail wasps (hymenopteran family Siricidae) upon which to lay eggs, males are listening for emerging females with which to mate. Upon sensing the vibrations emitted by a wood-boring host, the female wasp will drill her ovipositor into the substrate until it reaches the cavity wherein lies the host. She then injects an egg through the hollow tube into the body cavity. There the egg will hatch and the resulting larva will devour its host before emergence. How a female is able to drill with her ovipositor into solid wood is still somewhat of a mystery to science, though it has been found that there is metal (ionized manganese or zinc) in the extreme tip of some species' ovipositors.

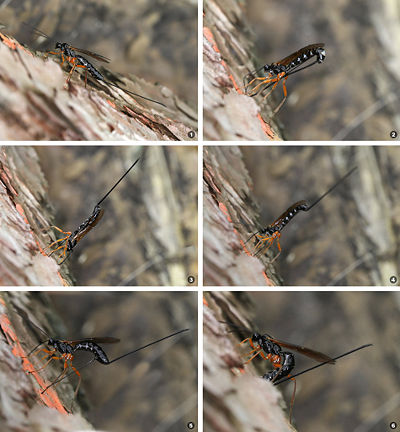

The process of oviposition in Dolichomitus imperator

- Tapping with her antennae the wasp listens for the vibrations that indicate a host is present.

- With the longer ovipositor, the wasp drills a hole through the bark.

- The wasp inserts the ovipositor into the cavity which contains the host larva.

- Making corrections.

- Depositing her eggs.

- Depositing her eggs.

Taxonomy and systematics

The taxonomy of the Ichneumonidae remains unsettled. About as diverse as the true weevils (Curculionidae), there are numerous small, inconspicuous, and hard-to-identify ichneumon wasps. The sheer diversity means that DNA sequence data is only available for a tiny fraction of the species, and that detailed cladistic studies require major-scale computing capacity.

Consequently, the phylogeny and systematics of the ichneumon wasps are not definitely resolved. Several prominent authors—like Townes (1969abc, 1971) and J. Oehlke (1966, 1967)—have gone as far as to publish major reviews that defy the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature.

Regardless, there exist a number of seminal works, including the extensive study and the synonymic catalog by Townes but also treatments by other entomologists, namely J.F. Aubert who has a fine collection of ichneumon wasps in Lausanne (Aubert 1969, 1978, 2000; Gauld 1976; Perkins 1959, 1960; Townes 1969abc, 1971; Townes et al. 1965).

Subfamilies

The list presented here follows the suggestion of David Wahl of the American Entomological Institute (Wahl 1999). It will be updated as necessary, as new research resolves the interrelationships of the ichneumonm wasps better.

The subfamilies are not listed in a taxonomic or phylogenetic sequence, as the relationships between the groups are not yet resolved to a degree to render any such arrangement even marginally reliable (Wahl 1999):

- Acaenitinae

- Agriotypinae

- Adelognathinae

- Anomaloninae (= Anomalinae)

- Banchinae

- Brachycyrtinae (sometimes included in Labiinae)

- Campopleginae (= Porizontinae)

- Collyriinae

- Cremastinae

- Cryptinae (= Gelinae, Hemitelinae, Phygadeuontinae)

- Ctenopelmatinae (= Scolobatinae)

- Cylloceriinae (= Oxytorinae, sometimes included in Microleptinae)

- Diacritinae (sometimes included in Pimplinae)

- Diplazontinae

- Eucerotinae (sometimes included in Tryphoninae)

- Ichneumoninae

- Labeninae (= Labiinae)

- Lycorininae (sometimes included in Banchinae)

- Mesochorinae

- Metopiinae

- Microleptinae

- Neorhacodinae (sometimes included in Banchinae)

- Ophioninae

- Orthocentrinae (sometimes included in Microleptinae)

- Orthopelmatinae

- Oxytorinae

- Paxylommatinae (sometimes not placed in Ichneumonidae at all)

- Pedunculinae

- Phrudinae

- Pimplinae (= Ephialtinae)

- Poemeniinae (sometimes included in Pimplinae)

- Rhyssinae (sometimes included in Pimplinae)

- Stilbopinae (sometimes included in Banchinae)

- Tatogastrinae (sometimes included in Microleptinae or Oxytorinae)

- Tersilochinae

- Tryphoninae

- Xoridinae

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aubert, J. F. 1969. Les Ichneumonides ouest-palearctiques et leurs hotes 1. Pimplinae, Xoridinae, Acaenitinae [The Western Palearctic ichneumon wasps and their hosts. 1. Pimplinae, Xoridinae, Acaenitinae.] Laboratoire d'Evolution des Etres Organises, Paris. [in French]

- Aubert, J. F. 1978. Les Ichneumonides ouest-palearctiques et leurs hotes 2. Banchinae et Suppl. aux Pimplinae [The Western Palearctic ichneumon wasps and their hosts. 2. Banchinae and supplement to the Pimplinae.] Laboratoire d'Evolution des Etres Organises, Paris & EDIFAT-OPIDA, Echauffour. [in French]

- Aubert, J. F. 2000. Les ichneumonides oeust-palearctiques et leurs hotes. 3. Scolobatinae (=Ctenopelmatinae) et suppl. aux volumes precedents [The West Palaearctic ichneumonids and their hosts. 3. Scolobatinae (= Ctenopelmatinae) and supplements to preceding volumes.] Litterae Zoologicae 5: 1-310. [French with English abstract]

- Fitton, M. G.. and I. D. Gauld. 1976. The family-group names of the Ichneumonidae (excluding Ichneumoninae) (Hymenoptera). Systematic Entomology 1: 247-258.

- Fitton, M. G., and I. D. Gauld. 1978. Further notes on family-group names of Ichneumonidae (Hymenoptera). Systematic Entomology 3: 245-247.

- Gauld, I. D. 1976. The classification of the Anomaloninae (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae). Bulletin of the British Museum of Natural History (Entomology) 33: 1-135.

- Grzimek, B., D. G. Kleiman, V. Geist, and M. C. McDade. 2004. Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Detroit: Thomson-Gale. ISBN 0787657883.

- Oehlke, J. 1966. Die westpaläarktische Arte des Tribus Poemeniini (Hymenoptera, Ichneumonidae) [The Western Palearctic species of the tribe Poemeniini]. Beiträge zur Entomologie 15: 881-892.

- Oehlke, J. 1967. Westpaläarktische Ichneumonidae 1, Ephialtinae. Hymenopterorum Catalogus (new edition) 2: 1-49.

- Perkins, J. F. 1959. Ichneumonidae, key to subfamilies and Ichneumoninae – 1. Handbk Ident. Br. Insects 7(part 2ai): 1–116.

- Perkins, J. F. 1960. Hymenoptera: Ichneumonoidea: Ichneumonidae, subfamilies Ichneumoninae 2, Alomyinae, Agriotypinae and Lycorininae. Handbk Ident. Br. Insects 7(part 2aii): 1–96.

- Sime, K., and A. Brower. 1998. Explaining the latitudinal gradient anomaly in ichneumonid species richness: Evidence from butterflies. Journal of Animal Ecology 67: 387-399.

- Townes, H. T. 1969a. Genera of Ichneumonidae, Part 1 (Ephialtinae, Tryphoninae, Labiinae, Adelognathinae, Xoridinae, Agriotypinae). Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute 11: 1-300.

- Townes, H. T. 1969b. Genera of Ichneumonidae, Part 2 (Gelinae). Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute 12: 1-537.

- Townes, H. T. 1969c. Genera of Ichneumonidae, Part 3 (Lycorininae, Banchinae, Scolobatinae, Porizontinae). Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute 13: 1-307.

- Townes, H. T. 1971. Genera of Ichneumonidae, Part 4 (Cremastinae, Phrudinae, Tersilochinae, Ophioninae, Mesochorinae, Metopiinae, Anomalinae, Acaenitinae, Microleptinae, Orthopelmatinae, Collyriinae, Orthocentrinae, Diplazontinae). Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute 17: 1-372.

- Townes, H. T., S. A. Momoi, and M. Townes. 1965. Catalogue and Reclassification of Eastern Palearctic Ichneumonidae. Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute 5: 1-661.

- Wahl, D. 1999. Classification and systematics of the Ichneumonidae (Hymenoptera). Version of July 19, 1999. C. A. Triplehorn Insect Collection, Ohio State University. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

External links

All links retrieved January 25, 2018.

- Reference large-format photos of 15 different species of Ichneumonidae

- Reference Photos: Giant Ichneumon Wasps - Male Megarhyssa sp.

- Key to subfamilies in Spanish and not all the families, but good photos.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.