Imbolc

| Imbolc | |

|---|---|

| Observed by | Gaels Irish people Scottish people Neopagans |

| Type | Gaelic, Celtic, Pagan |

| Date | Northern Hemisphere: February 2 Southern Hemisphere: August 1 |

| Related to | Candlemas |

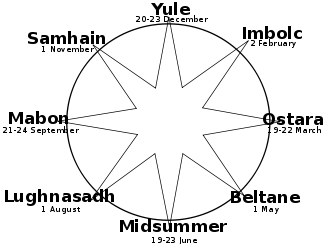

Imbolc or Imbolg (pronounced i-MOLK or i-MOLG), also called Saint Brighid’s Day (Irish: Lá Fhéile Bríde, Scottish Gaelic: Là Fhèill Brìghde, Manx: Laa’l Breeshey), is a Gaelic festival marking the beginning of spring. Most commonly it is held on January 31 – February 1, or halfway between the winter solstice and the spring equinox. It is one of the four Gaelic seasonal festivals, along with Beltane, Lughnasadh, and Samhain. It was observed in Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man. Kindred festivals were held at the same time of year in other Celtic lands; for example the Welsh Gŵyl Fair y Canhwyllau. The holiday is a festival of the hearth and home, and a celebration of the lengthening days and the early signs of spring. Rituals involve hearthfires, special foods, weather divination, candles, and an outdoor bonfire if the weather permits.

Imbolc is mentioned in some of the earliest Irish literature and it is associated with important events in Irish mythology. It has been suggested that it was originally a pagan festival associated with the goddess Brighid and that it was Christianized as a festival of Saint Brighid, who herself is thought to be a Christianization of the goddess. At Imbolc, Brighid's crosses were made and a doll-like figure of Brighid, called a Brídeóg, would be carried from house-to-house. Brighid was said to visit one's home at Imbolc. To receive her blessings, people would make a bed for Brighid and leave her food and drink, while items of clothing would be left outside for her to bless. Brighid was also invoked to protect livestock. Holy wells were visited and it was also a time for divination.

In Christianity, February 1st is observed as the feast day of Saint Brighid, especially in Ireland. There, some of the old customs have survived and it is celebrated as a cultural event. Since the twentieth century, Celtic neopagans and Wiccans have observed Imbolc, or something based on Imbolc, as a religious holiday.

Etymology

Irish imbolc derives from the Old Irish i mbolg "in the belly." This refers to the pregnancy of ewes.[1] A medieval glossary etymologizes the term as oimelc "ewe's milk."[2] Some Neopagans use Oimelc as the name of the festival.

Since Imbolc is immediately followed (on February 2) by Candlemas (Irish Lá Fhéile Muire na gCoinneal "feast day of Mary of the Candles," Welsh Gŵyl Fair y Canhwyllau),[3] Irish imbolc is sometimes rendered as "Candlemas" in English translation.[4]

Origins

Imbolc is one of the four Celtic seasonal festivals, along with Beltane, Lughnasadh, and Samhain.[5] It is most commonly held on January 31 – February 1, or halfway between the winter solstice and the spring equinox.[6][7]

However, Imbolc appears to have been important time to the earlier inhabitants of Ireland, since the Neolithic period.[8] This is inferred from the alignment of megalithic monuments, such as at the Loughcrew burial mounds and the Mound of the Hostages at the Hill of Tara. At such sites the inner chamber of the passage tombs is perfectly aligned with the rising sun of both Imbolc and Samhain. This is similar to the winter solstice phenomena seen at Newgrange, where the rising sun shines down the passageway and illuminates the inner chamber of the tomb.[8][9][10]

Customs

In Gaelic Ireland, Imbolc was the feis or festival marking the beginning of spring, during which great feasts were held. It is attested in some of the earliest Old Irish literature, from the tenth century onward.

Among agrarian peoples, Imbolc has been traditionally associated with the onset of lactation of ewes, soon to give birth to the spring lambs.[11] Since the timing of agrarian festivals can vary widely, given regional variations in climate, this could vary by as much as two weeks before or after the start of February.[1]

Since the weather was not conducive to outdoor gatherings, Imbolg celebrations were focused on the home. The holiday celebrated the lengthening days and the early signs of spring. Activities often involved hearthfires, special foods (butter, milk, and bannocks, for example), divination or watching for omens, candles, or a bonfire if the weather permitted.[6][7] Fire and purification were an important part of the festival. The lighting of candles and fires represented the return of warmth and the increasing power of the sun over the coming months.[1]

Holy wells were also visited at Imbolc, and at the other Gaelic festivals of Beltane and Lughnasadh. Visitors to holy wells would pray for health while walking 'sunwise' around the well. They would then leave offerings; typically coins or clooties (strips of cloth or rags). Water from the wells may have been used for blessings.[12]

Weather divination

Imbolc is the day the Cailleach — the hag goddess — gathers her firewood for the rest of the winter. Legend has it that if she intends to make the winter last a good while longer, she will make sure the weather on Imbolc is bright and sunny, so she can gather plenty of firewood. Therefore, people are generally relieved if Imbolc is a day of foul weather, as it means the Cailleach is asleep and winter is almost over.[13]

A Scottish Gaelic proverb about the day is:

Thig an nathair as an toll

Là donn Brìde,

Ged robh trì troighean dhen t-sneachd

Air leac an làir.

"The serpent will come from the hole

On the brown Day of Bríde,

Though there should be three feet of snow

On the flat surface of the ground."[14]

The old tradition of watching to see if serpents or badgers came from their winter dens on Imbolc may be a forerunner to the North American Groundhog Day.

Saint Brighid

Imbolc is strongly associated with Saint Brighid (Old Irish: Brigit, modern Irish: Bríd, modern Scottish Gaelic: Brìghde or Brìd, anglicized Bridget). Saint Brighid is thought to have been based on Brighid, a Gaelic goddess.[3] The festival, which celebrates the onset of spring, is be linked with Brighid in her role as a fertility goddess.[11]

Brighid is also associated with fire, used for warmth and cooking in the home. Thus, the celebration of Imbolg involved lighting fires and represented nurturing the physical body as well as the spiritual eternal flame of divinity.[15]

On Imbolc Eve, Brighid was said to visit virtuous households and bless the inhabitants as they slept.[16] As Brighid represented the light half of the year, and the power that will bring people from the dark season of winter into spring, her presence was very important.[7][14]

In the nineteenth century, families would have a supper on Imbolc Eve to mark the end of winter. Often, some of the food and drink would be set aside for Brighid. Before going to bed, items of clothing or strips of cloth would be left outside for Brighid to bless.[16] Ashes from the fire would be raked smooth and, in the morning, they would look for some kind of mark on the ashes as a sign that Brighid had visited.[16][12] The clothes or strips of cloth would be brought inside, and believed to now have powers of healing and protection.[7][14]

In the Isle of Man during the eighteenth century, the custom was to gather a bundle of rushes, stand at the door, and invite Brighid into the house by saying "Brede, Brede, come to my house tonight. Open the door for Brede and let Brede come in." The rushes were then strewn on the floor as a carpet or bed for Brighid. In the nineteenth century, some old Manx women would make a bed for Brighid in the barn with food, ale, and a candle on a table.[16]

In the Hebrides in the late eighteenth century, a bed of hay would be made for Brighid and someone would then go outside and call out three times: "a Bhríd, a Bhríd, thig a sligh as gabh do leabaidh" ("Bríd Bríd, come in; thy bed is ready"). In the early nineteenth century, the people of the Hebrides held feasts, at which women would dance while holding a large cloth and calling "Bridean, Bridean, thig an nall's dean do leabaidh" ("Bríd Bríd, come over and make your bed"). However, by this time the bed itself was rarely made.[16]

In Ireland and Scotland, girls and young women would make a Brídeóg (also called a 'Breedhoge' or 'Biddy'), a doll-like figure of Brighid made from rushes or reeds. It would be clad in bits of cloth, shells and/or flowers.[16][12] In the Hebrides of Scotland, a bright shell or crystal called the reul-iuil Bríde (guiding star of Brighid) was set on its chest. The girls would carry it in procession while singing a hymn to Brighid. All wore white with their hair unbound as a symbol of purity and youth. They visited every house in the area, where they received either food or more decoration for the Brídeóg. Afterwards, they feasted in a house with the Brídeóg set in a place of honor, and put it to bed with lullabies. When the meal was done, the local young men humbly asked for admission, made obeisance to the Brídeóg, and joined the girls in dancing and merrymaking until dawn.[16] Up until the mid twentieth century, children still went from house-to-house asking for money for the poor. In County Kerry, men in white robes went from house-to-house singing.[12]

Brighid's crosses were made at Imbolc. A Brighid's cross consists of rushes woven into a shape similar to a swastika, with a square in the middle and four arms protruding from each corner. They were often hung over doors, windows and stables to welcome Brighid and protect the buildings from fire and lightning. The crosses were generally left there until the next Imbolc. In western Connacht, people would make a Crios Bríde (Bríd's girdle); a great ring of rushes with a cross woven in the middle. Young boys would carry it around the village, inviting people to step through it and so be blessed.[16] Today, some people still make Brighid's crosses and Brídeógs or visit holy wells dedicated to St Brighid on February 1st.[12]

In the modern Irish Calendar, Imbolc is variously known as the Feast of Saint Brigid (Secondary Patron of Ireland), Lá Fhéile Bríde, and Lá Feabhra—the first day of Spring. Christians may call the day "Candlemas" or "the feast of the Purification of the Virgin."[7]

Neopaganism

Since the twentieth century, Celtic neopagans and Wiccans have observed Imbolc, or something based on Imbolc, as a religious holiday.[6][7]

Neopagans of diverse traditions observe this holiday in numerous ways. Some celebrate in a manner as close as possible to how the Ancient Celts and Living Celtic cultures have maintained the traditions, while others observe the holiday with rituals taken from numerous other unrelated sources, Celtic cultures being only one of the sources used.[17]

In more recent times the occasion has been generally celebrated by modern Pagans on February 1st or 2nd. Some Neopagans relate this celebration to the midpoint between the winter solstice and spring equinox, which actually falls later in the first week of the month. Since the Celtic year was based on both lunar and solar cycles, it is most likely that the holiday would be celebrated on the full moon nearest the midpoint between the winter solstice and vernal equinox.[14] Other Neopagans celebrate Imbolc when the primroses, dandelions, and other spring flowers emerge.[18]

Celtic Reconstructionist

Celtic Reconstructionist Pagans base their celebrations and rituals on traditional lore from the living Celtic cultures, as well as research into the older beliefs of the polytheistic Celts. They usually celebrate the festival when the first stirrings of spring are felt, or on the full moon that falls closest to this time. Many use traditional songs and rites from sources such as The Silver Bough and The Carmina Gadelica. It is especially a time of honoring the Goddess Brighid, and many of her dedicants choose this time of year for rituals to her.[18]

Wicca

Wiccans celebrate a variation of Imbolc as one of four "fire festivals," which make up half of the eight holidays (or "sabbats"), of the wheel of the year. Imbolc is defined as a cross-quarter day, midway between the winter solstice (Yule) and the spring equinox (Ostara). The precise astrological midpoint in the Northern hemisphere is when the sun reaches fifteen degrees of Aquarius. In the Southern hemisphere, if celebrated as the beginning of Spring, the date is the midpoint of Leo. Among Dianic Wiccans, Imbolc (also known as "Candlemas") is the traditional time for initiations.[19]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Nora Chadwick, The Celts (Penguin, 1971, ISBN 978-0140212112).

- ↑ Kuno Meyer, Sanas Cormaic (Cormacs Glossary) (Llanerch Press, 1994, ISBN 978-1897853269).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 James MacKillop, Dictionary of Celtic mythology (Oxford University Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0192801203).

- ↑ Leo Ruickbie, Imbolc (Candlemas) Sabbat Witchology, the history of Wicca & Witchcraft.

- ↑ Barry Cunliffe, The Ancient Celts (Penguin, 2000, ISBN 978-0140254228).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Kevin Danaher, The Year in Ireland: Irish Calendar Customs (Dublin: Mercier, 2001, ISBN 978-1856350938).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 F. Marian McNeill, Silver Bough: Calendar of Scottish National Festivals, Vol. 1–4. (Glasgow: Stuart Titles Ltd, 1990, ISBN 978-0948474040).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Imbolc (Imbolg) - Cross Quarter Day Newgrange.com. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ↑ Michael J. O'Kelly, Early Ireland: An Introduction to Irish Prehistory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989, ISBN 978-0521336871).

- ↑ Michael Dames, Mythic Ireland (London, Thames & Hudson, 1996, ISBN 978-0500278727).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 John T. Koch, Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia (ABC-CLIO, 2006, ISBN 978-1851094400).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Patricia Monaghan, The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore (Checkmark Books, 2008, ISBN 978-0816075560).

- ↑ Katharine Briggs, An Encyclopedia of Fairies (New York, NY: Pantheon Books, 1976, ISBN 039473467X).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Alexander Carmichael, Carmina Gadelica: Hymns and Incantations (Lindisfarne Press, 1992, ISBN 978-0940262508). Available online at The Sacred Texts Archive. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ↑ Claire Hamilton, Celtic Book of Seasonal Meditations: Celebrate the Traditions of the Ancient Celts (York Beach, ME: Red Wheel/Weiser, 2003, ISBN 1590030559).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 16.7 Ronald Hutton, Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain (Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0192854483).

- ↑ Margot Adler, Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1981, ISBN 978-0807032374).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Isaac Bonewits, Bonewits's Essential Guide to Druidism (New York, NY: Kensington Publishing Group, 2006, ISBN 978-0806527109).

- ↑ Zsuzsanna Budapest, The Holy Book of Women's Mysteries (Wingbow Press, 1989, ISBN 978-0914728672).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adler, Margot. Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1981. ISBN 978-0807032374

- Bonewits, Isaac. Bonewits's Essential Guide to Druidism. New York, NY: Kensington Publishing Group, 2006. ISBN 978-0806527109

- Briggs, Katharine Mary. An Encyclopedia of Fairies. New York, NY: Pantheon Books, 1976. ISBN 039473467X

- Budapest, Zsuzsanna. The Holy Book of Women's Mysteries. Wingbow Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0914728672

- Cabot, Laurie, and Jean Mills. Celebrate the Earth: A Year of Holidays in the Pagan Tradition. New York, NY: Dell Publishing, 1994. ISBN 0385309201

- Carmichael, Alexander. Carmina Gadelica: Hymns & Incantations. Lindisfarne Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0940262508

- Chadwick, Nora. The Celts. London: Penguin, 1971. ISBN 978-0140212112

- Cunliffe, Barry. The Ancient Celts. Penguin, 2000, ISBN 978-0140254228

- Dames, Michael. Mythic Ireland. London, Thames & Hudson, 1996. ISBN 978-0500278727

- Danaher, Kevin. The Year in Ireland. Dublin: Mercier, 2001. ISBN 978-1856350938

- Hamilton, Claire. Celtic Book of Seasonal Meditations: Celebrate the Traditions of the Ancient Celts. York Beach, ME: Red Wheel/Weiser, 2003. ISBN 1590030559

- Koch, John T. Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2006. ISBN 978-1851094400

- MacKillop, James. Dictionary of Celtic mythology. Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0192801203

- McNeill, F. Marian. Silver Bough: Calendar of Scottish National Festivals, Vols. 1-4. Glasgow: Stuart Titles Ltd, 1990. ISBN 978-0948474040

- Meyer, Kuno. Sanas Cormaic (Cormacs Glossary). Llanerch Press, 1994. ISBN 978-1897853269

- Monaghan, Patricia. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. Checkmark Books, 2008. ISBN 978-0816075560

- Ó Catháin, Séamas. Festival of Brigit: Celtic Goddess and Holy Woman. Dublin: DBA Publications, 1995. ISBN 0951969226

- O'Kelly, Michael J. Early Ireland: An Introduction to Irish Prehistory. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0521336871

External links

All links retrieved February 25, 2018.

- Imbolc (Imbolg) - Cross Quarter Day

- Tara - Temair Mythical Ireland.

- The Festival of Brigit the Holy Woman (Oiche Fhéile Bríde agus Lá Lúnasa)

- Saint Brigid & Spring — bilingual, Irish folklore

- Imbolc: A Day for the Queen of Heaven by Jonathan Young

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.