Absolution

Absolution is the act of receiving forgiveness for one's sins or wrongdoings, by being set free from guilt or penalty. Most religions have some concept of absolution, whether expressed ritually or not.

Ancient Jewish religion involved rites of priestly sacrifice of animal or vegetable offerings, by which a person who had sinned could receive absolution. Early Christianity abandoned this practice in favor of a belief that Christ, by his death on the Cross, had performed the ultimate sacrifice to absolve all believers of their sins through their repentance, faith, and baptism. Later church tradition developed a formal liturgy by which believers could receive absolution from a priest for sins committed after baptism, including the most serious "mortal sins." The Protestant Reformation downplayed the role of the priest in the process of absolution and evolved various traditions regarding the minister's role in the process, if any.

While contemporary Judaism has abandoned formal sacrificial rituals of absolution, Jews still have the duty to seek forgiveness from those against whom they have sinned, both humans and God. Absolution is also an important part of Muslim worship, where it is known as Istighfar. Buddhism also involves a tradition of confession and absolution, especially for monks and nuns. In Hinduism an act or rite of seeking absolution is known as Prayaschitta, or penance to ease karma.

Ancient Jewish tradition

In the Hebrew Bible, God's forgiveness of sin was a major concern in the tradition of the Temple of Jerusalem and its priesthood. By bringing various offerings to the Temple, individuals, leaders, and the whole congregation of the Israelites could receive absolution for their sins. Traditionally, the practice of sin-offerings and the resulting absolution dates back to the time of the Exodus. The Book of Leviticus, for example, stipulates that: "If a member of the community sins unintentionally…he must bring…a female goat without defect…. The priest will make atonement for him, and he will be forgiven." (Leviticus 4:27-31). Female lambs were also acceptable as sin-offerings, and if the person could not afford this, birds or flour could be substituted as well. An unintentional sin committed by a leader of the congregation required the sacrifice of a male goat rather than a female (4:22). If the whole Israelite community sinned, the assembly was to bring a young bull as a sin-offering.

Some intentional sins, such as fornication with a slave girl, could be forgiven through sin-offerings. If the girl were free-born, the penalty was to by pay a fine to her father and marry her (Deuteronomy 22). Some sins committed intentionally, however, could not be absolved but were to be punished by expulsion from the congregation of Israel: "Anyone who sins defiantly, whether native-born or alien, blasphemes the Lord, and that person must be cut off from his people." (Numbers 15:30)

Various other regulations also governed the absolution of sin, such as the payment of the "sanctuary shekel" (Lev. 5:16): "He must make restitution for what he has failed to do in regard to the holy things." Monetary restitution was also involved in cases of theft, in which case: "He must make restitution in full, add a fifth of the value to it and give it all to the owner," and also make a guilt-offering. Absolution from ritual impurity, such as an emission of semen for men or menstruation for women, involved certain bathing rituals and the offering of two young pigeons.

Some sins were considered so grievous that they must be punished with death. These included murder, adultery, homosexual acts sodomy, blasphemy, idolatry, cursing one's parent, and sabbath-breaking. It is not clear how strictly these rules were enforced, however.

Earliest Christianity

In the New Testament, John the Baptist's ministry was one of absolution: "John came, baptizing in the desert region and preaching a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins." (Mark 1:4) Jesus, too, baptized people and also verbally absolved them of their sins (Matthew 9:2, etc.). In his teaching, he established a correlation between God's absolution of human sin and people absolving their fellows: "If you forgive men when they sin against you, your heavenly Father will also forgive you. But if you do not forgive men their sins, your Father will not forgive your sins." (Matthew 6:14-15)

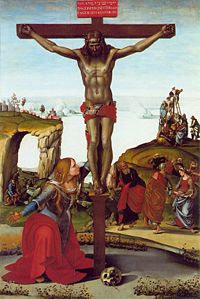

After Jesus' death, the first Christians were Jews who generally followed the Jewish law regarding absolution, adding to it Jesus' teachings such as those above. However, especially through the teaching of Paul of Tarsus, the crucifixion of Jesus soon came to be seen as an atoning sacrifice made "once for all." Absolution for sins against God was thus no longer a matter of offering sacrifices through the Temple priests, but having faith in Jesus and being baptized.

For Paul, "our old self was crucified with him… that we should no longer be slaves to sin." (Rom. 6:6-7) The anonymous Epistle to the Hebrews portrayed Christ as the true "high priest" whose sacrifice of his own body was the sin-offering made on behalf of all those who believe in him. Thus, once one had faith in Christ and had been baptized, offerings made at the Temple were no longer necessary.

After the Temple of Jerusalem itself was destroyed in 70 C.E., Jewish Christianity quickly declined and Pauline Christianity soon predominated. Baptized Christians were believed to have been forgiven of all previous sins. After baptism, one was a "new creature in Christ" and was supposed to live a holy life as a "saint," a term referring to any member of the Christian church, which was seen as the "body of Christ." However, the question remained as to how sins committed after baptism could be absolved.

Paul counseled that certain sins, especially the teaching of false doctrines and serious sexual sins, should not be forgiven by the church, but that those who committed them should be expelled or even turned in to the authorities for their crimes.

"A man has his father's wife… hand this man over to Satan, so that the sinful nature may be destroyed and his spirit saved on the day of the Lord…. You must not associate with anyone who calls himself a brother but is sexually immoral or greedy, an idolater or a slanderer, a drunkard or a swindler. With such a man do not even eat." (1 Corinthians 5:1-5)

An especially difficult issue was what the Hebrew Bible had called "sins unto death," or mortal sins, which could not be forgiven by normal means of atonement in Jewish tradition. Could Christians who committed sins of this magnitude be forgiven and welcomed into full fellowship? Hoping to avoid post-baptismal sins, many early Christians turned to asceticism and hoped for the rapid return of Jesus, but as this was prolonged, many found themselves in a state of mortal sin without a clear means to receive absolution.

Evolving traditions of absolution

In the second century, the Montanist movement stressed a puritanical lifestyle and adopted a strict moral standard, in which certain sins like murder, adultery, and apostasy could not be forgiven. The Church Fathers Tertullian was among the adherents of this policy. The popular apocalyptic writing known as the Shepherd of Hermas promised one final absolution of post-baptismal mortal sins before the imminent Second Coming of Christ. Some new converts, knowing that they could not avoid committing sins, even postponed baptism until they were on the death-bed.

In the third and fourth centuries the issue of apostates returning to the church was especially contentious. The Novatianists held that those who denied the faith and committed idolatry could not be granted absolution by the church, for only God could forgive a mortal sin. The "catholic" (meaning universal) position, on the other hand, held that the church must be a home to sinners as well as saints, and that the bishops, as successors to Peter and the apostles, were authorized by God to forgive any sin.

It became the practice of penitent apostates to go to the confessors—those who had suffered for the faith and survived—to plead their case and effect their restoration to communion with the bishop's approval. The Catholic Church thus began to develop the tradition of confession, penance, and absolution, in order to provide a means for Christians to be forgiven of sins committed after baptism, including even mortal sins.

Catholicism

Absolution became an integral part of both the Catholic and Orthodox sacrament of penance and reconciliation. In the Catholic tradition, the penitent makes a formal confession of all mortal sins to a priest and prays an act of contrition. The priest then assigns a penance and offers absolution in the name of the Trinity, on behalf of the Church:

"God, the Father of mercies, through the death and resurrection of his Son has reconciled the world to himself and sent the Holy Spirit among us for the forgiveness of sins; through the ministry of the Church may God give you pardon and peace, and I absolve you from your sins in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen."

This prayer of absolution by the priest, as God's minister, is believed to forgive the guilt associated with the penitent's sins and to remove the eternal punishment (in Hell) associated with mortal sins. However, the penitent is still responsible for the temporal punishment (in Purgatory) associated with the confessed sins, unless an indulgence is applied. If the sin is also a crime under secular law, the Church's forgiveness does not absolve the person of the need to pay his debt to society through fines, imprisonment, or other punishment.

Another form of absolution in Catholic tradition is general absolution, in which all eligible Catholics gathered at a given area are granted absolution for sins without prior individual confession to a priest. General absolution is authorized in only two circumstances:

- Imminent danger of death and there is no time for a priest or priests to hear the confessions of the individual penitents. A recent example was the general absolution granted to all Catholics endangered by the Three Mile Island nuclear accident.

- Other extraordinary and urgent needs: for example if the number of penitents is so large that there are not enough priests to hear the individual confessions properly within a reasonable time (generally considered to be one month). The diocesan bishop must give prior permission before general absolution is dispensed under this circumstance.

For a valid reception of general absolution, the penitent must be contrite for all his mortal sins and have the resolution to confess at the next earliest opportunity each of those mortal sins that is forgiven in general absolution. Anyone receiving general absolution is also required to make a complete individual confession to a priest as soon as possible before receiving general absolution again.

Othodoxy

The Orthodox practice of absolution is equally ancient to that of the Catholic, although the tradition of confession is less formal and may be administered by a layperson as well as a priest. In modern times, the practice of absolution was reaffirmed by the Synod of Constantinople in 1638, the Synod of Jassy in 1642 and the Synod of Jerusalem, 1672, etc. The Synod of Jerusalem specified the Orthodox belief in seven sacraments, among them penance—involving both confession and absolution—which Christ established when he said: "Whose sins you shall forgive they are forgiven them, and whose sins you shall retain they are retained." (John 20:23)

After one confesses, the priest—who may or may not have heard the confession—covers the head of the person with his stole and reads the prayer of absolution, asking God to forgive the transgression of the individual. The Orthodox version of absolution, in contrast to the Catholic, stresses the unworthiness of the minister to forgive sin, which God alone can do. In the Greek practice, the priest says: "Whatever you have said to my humble person, and whatever you have failed to say, whether through ignorance or forgetfulness, whatever it may be, may God forgive you in this world and the next…" One version of the Russian Orthodox prayer of absolution states: "May Our Lord and God, Jesus Christ, through the grace and bounties of His love towards mankind, forgive you, my Child, all your transgressions. And I, an unworthy Priest, through the power given me by Him, forgive and absolve you from all yours sins."

Several variations of the Orthodox formula are found in different regional and linguistic traditions.

Protestantism

The Protestant Reformation brought an emphasis on the "priesthood of all believers" and a consequent diminution in the role of priests as agents of absolution. However various attitudes and specific traditions of absolution soon emerged among the Protestant denominations.

In Lutheranism, personal repentance and faith in Jesus' atoning sacrifice are considered sufficient conditions for absolution. However, although the Lutherans completely eliminated the practice of acts of contrition, they retained the rites of confession and absolution with a priest. More recently, these formal rites have been downplayed and are practiced only when requested by the penitent or recommended by the confessor or pastor.

The Swiss reformer Huldrych Zwingli, on the other hand, saw nothing but idolatry in the practice involving a human agent in absolution, holding that God alone pardoned sin. John Calvin denied that penance was an authentic sacrament, but he held that the absolution expressed by the minister of the church was helpful to the penitent's sense of forgiveness. The attitude of the Presbyterian and other Reformed churches derives from these traditions.

In the Anglican Communion, whose break from Rome was less about sacraments than about church politics, absolution usually takes place after the General Confession during the Eucharist or a daily office, and is a component of the sacrament of confession and absolution. It may also be pronounced after the reconciliation of a penitent by the priest hearing a private confession.

Protestant traditions of the Radical Reformation (such as Baptists, Anabaptists, and Mennonites—as well as some in the later Restoration Movement such as the Church of Christ and Disciples of Christ—stress absolution as taking place primarily at the time of baptism. These and other Protestants reject the idea that the minister has any role at all in absolution, except insofar as his preaching and praying may help the individual believer develop a greater sense of having received God's forgiveness.

Other religions

Most religions have some kind of concept of absolution even if they do not have formal rituals related to it. Judaism, which once involved highly formalized traditions of absolution through ritual sacrifice, has evolved in the rabbinic era into a religion in which absolution for sins against God is obtained through prayer.

For sins against humans, however, one must go to those who have been harmed in order to receive absolution from them. According to the compilation of Jewish law known as the Shulchan Aruch (OC 606:1) a person who sincerely apologizes three times for a wrong committed against another has fulfilled his or her obligation to seek forgiveness. In association with the holiday of Yom Kippur, Jews are supposed to ask forgiveness from any persons from whom they have not yet received absolution. They also fast and pray for God's forgiveness for the sins they have committed against God.

In Islam, absolution is one of essential parts of worship. However, just as in Judaism, it does not involve the action of a priest. The act of seeking absolution is called Istighfar. It is generally done by repeating the Arabic phrase astaghfirullah, meaning "I seek forgiveness from Allah," while praying. Many Muslims use this phrase often, even in casual conversation. After every formal prayer, a Muslim will typically recite the phrase three or more times. Even if a Muslim only sins internally, such as by experiencing feelings of envy, jealousy, arrogance, or lust, he is supposed to ask absolution from Allah in this fashion.

In Buddhist tradition, the disciples of the Buddha are portrayed as sometimes confessing their wrongdoings to Buddha and receiving absolution from him. Confessing one's faults to a superior and receiving penance and absolution is an important part of the spiritual practice of many Buddhist monks and nuns.

The concept of asking for forgiveness and receiving absolution is also a part of the practice of Hinduism, related to the Sanskrit concept of Prayaschitta. The term denotes an act or rite intended for the destruction of sin. Derived from the law of Karma, Prayashitta must be performed not only to restore one's sense of harmony with the Divine, but also to avoid the future consequences of sin, either in this life or the next.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barton, John M. T. "Penance and Absolution." Twentieth century Encyclopedia of Catholicism, 51. Section 5: The life of faith. New York: Hawthorn Books, 1961. OCLC 331592

- Firey, Abigail. A New History of Penance. Leiden: Brill, 2008. ISBN 9789004122123.

- MacArthur, John. Confession of Sin. Chicago: Moody Press, 1986. ISBN 9780802450937.

- McMinn, Mark R. Why Sin Matters: The Surprising Relationship Between Our Sin and God's Grace. Wheaton, IL: Tyndale House, 2004. ISBN 9780842383660.

- Osborne, Kenan B. Reconciliation and Justification: The Sacrament and Its Theology. New York: Paulist Press, 1990. ISBN 9780809131433.

- Tentler, Thomas N. Sin and Confession on the Eve of the Reformation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1977. ISBN 9780691072197.

External Links

All links retrieved June 14, 2023.

- Absolution Catholic Encyclopedia

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.