Adhesive

An adhesive is a material that can adhere (stick) to other materials and help attach them together. The state of attachment is known as adhesion, which is based on the attraction between molecules of the items in contact.

Various types of adhesives are now available, derived from natural and synthetic sources. Some modern synthetic adhesives are extremely strong and are increasingly used in construction and industry.

History

It appears that the earliest adhesives used in history were natural gums and other plant resins. Archaeologists have found six-thousand-year-old ceramic vessels that had broken and been repaired with plant resin. Native Americans, in what is now the eastern United States, used a mixture of spruce gum and fat as adhesives and caulking to waterproof seams in their birch bark canoes. In ancient Babylonia, tar-like glue was used for gluing statues.

There is also evidence that many early adhesives were glues made from animal products. For instance, Native Americans made glues from buffalo hooves. Early Egyptians used animal glues to repair fractures in tombs, furniture, ivory, and papyrus. The Mongols used adhesives to make their short bows.

In Europe in the Middle Ages, egg whites were used to decorate parchments with gold leaves. In the 1700s, the first glue factory was founded in Holland, which manufactured hide glue. Later, in the 1750s, the British introduced fish glue. As modernization continued, new patents were issued for the use of rubber, bones, starch, fish, and casein. Modern synthetic adhesives have improved flexibility, toughness, curing rate, temperature, and chemical resistance.

Types of adhesives

Adhesives may be classified as natural or synthetic. Examples of natural adhesives are plant resins, glues from animal hide and skin, and adhesives from mineral (inorganic) sources. Examples of synthetic adhesives are polymers such as elastomers, thermoplastics, and thermosets. Adhesives may also be grouped according to their properties, as follows.

Drying adhesives

These adhesives are a mixture of ingredients (typically polymers) dissolved in a solvent. Glues such as white glue, and rubber cements are members of the drying adhesive family. As the solvent evaporates, the adhesive hardens. Depending on the chemical composition of the adhesive, it will adhere to different materials to a greater or lesser extent. These adhesives are typically weak and are used for household applications. Those intended for use by small children are made nontoxic.

Contact adhesives

A contact adhesive is one that must be applied to both surfaces and allowed some time—sometimes as much as 24 hours—to dry before the two surfaces are pushed together.[1] Once the surfaces are brought together, the bond forms very quickly,[2] and it is usually not necessary to apply pressure for a long time. In other words, there is often no need to use clamps, which is convenient.

Hot (thermoplastic) adhesives

Also known as "hot melt" adhesives, these thermoplastics are applied hot and simply allowed to harden as they cool. They have become popular for crafts because of their ease of use and the wide range of common materials to which they can adhere. A glue gun is one method of applying a hot adhesive. The solid adhesive melts in the body of the gun, and the liquefied material passes through the barrel of the gun onto the material where it solidifies.

Reactive adhesives

A reactive adhesive works by chemical bonding with the surface material. It is applied as a thin film. Reactive adhesives include two-part epoxy, peroxide, silane, isocyanate, or metallic cross-linking agents. They are less effective when there is a secondary goal of filling gaps between surfaces.

Such adhesives are frequently used to prevent the loosening of bolts and screws in rapidly moving assemblies, such as automobile engines. They are largely responsible for the quieter running modern car engines.

Pressure-sensitive adhesives

Pressure sensitive adhesives (PSAs) form a bond by the application of light pressure to bind the adhesive to the adherend (substrate for attachment). They are designed with a balance between flow and resistance to flow. The bond forms because the adhesive is soft enough to flow and "wet" the adherend. The bond has strength because the adhesive is hard enough to resist flow when stress is applied to the bond. Once the adhesive and adherend are in close proximity, interactions between their molecules contribute significantly to the ultimate strength of the bonding. PSAs are manufactured with either a liquid carrier or in completely solid form.

PSAs are designed for either permanent or removable applications. Examples of permanent applications include safety labels for power equipment, foil tape for HVAC duct work, automotive interior trim assembly, and sound/vibration damping films. Some high-performance permanent PSAs can support kilograms of weight per square centimeter of contact area, even at elevated temperatures. Permanent PSAs may be initially removable (such as to recover mislabeled goods) and set to a permanent bond after several hours or days.

Removable PSAs are designed to form a temporary bond and ideally can be removed after months or years without leaving residue on the adherend. They are used in applications such as surface protection films, masking tapes, bookmark and note papers, price marking labels, and promotional graphics materials. Plastic wrap displays temporary adhesive properties as well. In medical applications, they are used in cases where skin contact needs to be made, such as for wound care dressings, EKG electrodes, athletic tape, and analgesic and transdermal drug patches. Some removable adhesives are designed to repeatedly stick and unstick. They have low adhesion and generally cannot support much weight.

Mechanisms of adhesion

The strength of attachment between an adhesive and its substrate depends on many factors, including the mechanism by which this occurs and the surface area over which the two materials contact each other. Materials that wet each other tend to have a larger contact area than those that don't. Five mechanisms have been proposed to explain why one material sticks to another.

Mechanical Adhesion

Two materials may be mechanically interlocked, such as when the adhesive works its way into small pores of the materials. Some textile adhesives form small-scale bonds. On larger levels, mechanical bonds can be formed by sewing or the use of velcro.

Chemical Adhesion

Two materials may form a compound at the join. The strongest joins are where atoms of the two materials swap electrons (in cases of ionic bonds) or share electrons (in cases of covalent bonds). Weaker bonds (known as hydrogen bonds) are formed if oxygen, nitrogen, or fluorine atoms of the two materials share a hydrogen nucleus.

Dispersive Adhesion

In dispersive adhesion (also known as adsorption), two materials are held together by what are known as "van der Waals forces." These are weak (but numerous) interactions between molecules of the materials, arising by electron movements or displacements within the molecules.

Electrostatic Adhesion

Some conducting materials may pass electrons to form a difference in electrical charge at the join. This gives rise to a structure similar to a capacitor and creates an attractive electrostatic force between the materials.

Diffusive Adhesion

Some materials may merge at the joint by diffusion. This may occur when the molecules of both materials are mobile and soluble in each other. This would be particularly effective with polymer chains, where one end of a molecule of one material diffuses into molecules of the other material. It is also the mechanism involved in sintering. When metal or ceramic powders are pressed together and heated, atoms may diffuse from one particle to the next, thereby joining the particles together.

Fracturing of the adhesive joint

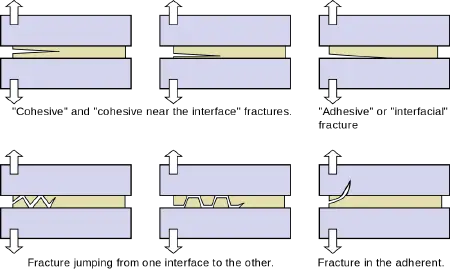

When a load is placed on materials held together by an adhesive, the adhesive joint may fracture. There are several major types of fracture, as follows.

- Cohesive fracture: A "cohesive" fracture is formed if a crack propagates in the bulk polymer that constitutes the adhesive. In this case, the surfaces of both adherents will be covered by fractured adhesive. The crack may propagate near the center of the layer or near an interface.

- Interfacial fracture: The fracture is said to be "adhesive" or "interfacial" when separation occurs at the interface between the adhesive and the adherend. The interfacial character of a fracture surface is usually detected by visual inspection, but advanced surface characterization techniques (such as spectrophotometry) allow one to locate the crack precisely.

- Mixed fracture: This is a case in which the crack propagates at some spots in a “cohesive” manner and in other areas in an “interfacial” manner.

- Alternating crack path fracture: In this case, the cracks jump from one interface to the other. This type of fracture appears in the presence of tensile pre-stresses in the adhesive layer.

In some cases, the adherend (substrate) may fracture while the adhesive, being tougher, may remain intact.

Consider some examples of different types of fractures. When one removes a price label attached to a product, adhesive usually remains partially on the label and partially on the surface of the product. This is a case of cohesive failure. If, however, a layer of paper remains stuck to the surface, the adhesive has not failed, but the fracture has occurred in one of the substrates. An example of an adhesive failure is when someone pulls apart an Oreo cookie and all the filling remains on one side.

Examples of glues

Historically, the term "glue" referred to protein colloids prepared from animal tissues. The meaning has been extended to any glue-like substance used to attach one material to another. Below are some examples of adhesives commonly referred to as glues.

- Cyanoacrylate (brand names Super Glue, Krazy Glue)

- Casein glue (protein glue)

- Postage stamp gum

- Cement glues:

- Contact cement

- Rubber cement

- Pyroxylin cement

- Plastic cement (technically a solvent, not a glue)

- Resin glues:

- Epoxy resins

- Acrylic resin

- Phenol formaldehyde resin

- Polyvinyl acetate (PVA), including white glue (such as Elmer's glue) and yellow carpenter's glue (aliphatic resin)

- Glue sticks (PVP (polyvinyl pyrrolidone) or PVA based)

- Polyester resin

- Resorcinol resin

- Urea-resin glue (plastic resin)

- Urea-formaldehyde resin

- Canada balsam

- Pastes:

- Latex pastes

- Vegetable-based glues:

- Mucilage

- Starch glue

- Soybean glue

- Tapioca paste (commonly known as "vegetable glue")

- Animal glues:

- Hide glue (flake and liquid versions)

- Bone glue

- Fish glue

- Rabbit skin glue

- Horse

- Hoof glue

- Hot melt glue

- Polyethylene hot melt

- Acrylonitrile

- Cellulose nitrate

- Latex combo

- Neoprene base

- Polysulfide

- Polyurethane

- Polyvinyl chloride (PVC)

- Rubber base

- Silicon base

- Albumin glue

- Ceramic adhesive

- Ultraviolet glue

Notes

- ↑ Contact Adhesives ThisToThat. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- ↑ What are some of the uses for contact cement? HowSTuffWorks. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Comyn, John. Adhesion Science. Royal Society of Chemistry Paperbacks, 1997. ISBN 0854045430

- Kinloch, A. J. Adhesion and Adhesives: Science and Technology. Chapman and Hall, 1987. New edition, 2001. Springer. ISBN 041227440X

- Veslovsky, Roman A. and. Vladimir. N. Kestelman. Adhesion of Polymers. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional, 2001. ISBN 0071370455

External links

All links retrieved June 15, 2023.

- The Adhesion Society

- ThomasNet - Directory of manufacturers and distributors of adhesives

- Educational portal on adhesives and sealants

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.