Adoption

|

| Family law |

|---|

| Entering into marriage |

| Marriage |

| Common-law marriage |

| Dissolution of marriage |

| Annulment |

| Divorce |

| Alimony |

| Issues affecting children |

| Illegitimacy |

| Adoption |

| Child support |

| Foster care |

| Areas of possible legal concern |

| Domestic violence |

| Child abuse |

| Adultery |

| Polygamy |

| Incest |

Adoption is the legal act of permanently placing a child with a parent or parents other than the birth parents. Adoption results in the severing of the parental responsibilities and rights of the biological parents and the placing of those responsibilities and rights onto the adoptive parents. Unlike guardianship or other systems designed for the care of the young, adoption is intended to effect a permanent change in status and as such requires societal recognition, either through legal or religious sanction. After the finalization of an adoption, there is generally no legal difference between biological and adopted children, though exceptions may apply in some jurisdictions.

However, adoption is by no means solely a legal issue. Changing the lineage, and possibly the culture and even ethnic group of an individual has implications on all levels of human life—physical, psychological, social, and spiritual. To be successful, adoption must address the situations of the biological parents, the adoptive parents, and the adopted children.

Reasons for Adoption

Adoptions occur for many reasons. The most common reason is that children are placed for adoption as a result of the biological parents' or parent's decision that they are unable to adequately care for a child. In some countries, where single motherhood may be considered scandalous and unacceptable, some women in this situation make an adoption plan for their infants, whereas others may come under financial, societal, or familial pressure to choose adoption. In some cases, they abandon their children at or near an orphanage, so that they can be adopted. In some cases and some cultures, parents prefer one gender over another and place any baby who is not the preferred gender for adoption.

Some biological parents involuntarily lose their parental rights. This usually occurs when the children are placed in foster care because they were abused, neglected, or abandoned. Eventually, if the parents cannot resolve the problems that caused or contributed to the harm caused to their children (such as alcohol or drug abuse), a court may terminate their parental rights and the children may then be adopted.

Only a small percentage of adopted children are orphans whose biological parents died. The main reason for adopting varies from one country to the next, depending largely on social and legal structures. The inability to reproduce biologically is a common reason. The most prevalent obstacle to producing a biological child is infertility. Another obstacle is the lack of a partner of the opposite sex or a lack of desire to use a surrogate or sperm donor. Single people and same-sex couples often adopt for this reason.

Some couples or individuals adopt children even though they are fertile. Some may choose to do this in order to avoid contributing to perceived overpopulation, or out of the belief that it is more responsible to care for otherwise parent-less children than to reproduce. Others may do so to avoid passing on serious heritable diseases, or out of health concerns relating to pregnancy and childbirth. Others believe that it is an equally valid form of family building, neither better nor worse than the biological route. Many are motivated by the desire to help others that are in need no matter what race or culture they represent. In many Western countries, stepparent adoption is the most common form of adoption as people choose to cement a new family following divorce or death of one parent.

History

Adoption has a long history in the Western world, closely tied with the legacy of the Roman Empire and the Catholic Church. Its use has changed considerably over the centuries with its focus shifting from adult adoption and inheritance issues toward children and family creation.

Antiquity

- Adoption for the well-born

While the modern form of adoption emerged in the United States, forms of the practice appeared throughout history.[1] The Code of Hammurabi, for example, details the rights of adopters and the responsibilities of adopted individuals at length and the practice of adoption in ancient Rome is well documented in the Codex Justinianus.[2][3]

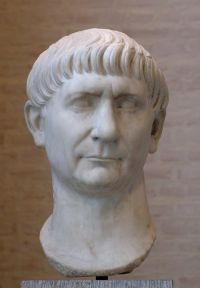

Markedly different from the modern period, ancient adoption practices put emphasis on the political and economic interests of the adopter,[4] providing a legal tool that strengthened political ties between wealthy families and creating male heirs to manage estates.[5] The use of adoption by the aristocracy is well documented; many of Rome's emperors were adopted sons.[6]

Infant adoption during Antiquity appears rare.[4] Abandoned children were often picked up for slavery and composed a significant percentage of the Empire’s slave supply.[7] Roman legal records indicate that foundlings were occasionally taken in by families and raised as a son or daughter. Although not normally adopted under Roman Law, the children, called alumni, were reared in an arrangement similar to guardianship, being considered the property of the father who abandoned them.[7]

Other ancient civilizations, notably India and China, also utilized some form of adoption. Evidence suggests their practices aimed to ensure the continuity of cultural and religious practices, in contrast to the Western idea of extending family lines. In ancient India, secondary sonship continued, in a limited and highly ritualistic form, so that an adopter might have the necessary funerary rites performed by a son.[8] China had a similar conception of adoption with males adopted solely to perform the duties of ancestor worship.[9]

Middle Ages to Modern Period

- Adoption and commoners

The nobility of the Germanic, Celtic, and Slavic cultures that dominated Europe after the decline of the Roman Empire denounced the practice of adoption. In medieval society, bloodlines were paramount; a ruling dynasty lacking a natural-born heir apparent was replaced, a stark contrast to Roman traditions. The evolution of European law reflects this aversion to adoption. English Common Law, for instance, did not permit adoption since it contradicted the customary rules of inheritance. In the same vein, France's Napoleonic Code made adoption difficult, requiring adopters to be over the age of 50, sterile, older than the adopted person by at least fifteen years, and to have fostered the adoptee for at least six years.[4]

Europe's cultural makeover marked a period of significant innovation for adoption. Without support from the nobility, the practice gradually shifted toward abandoned children. Abandonment levels rose with the fall of the empire and many of the foundlings were left on the doorstep of the Church.[7] Initially, the clergy reacted by drafting rules to govern the exposing, selling, and rearing of abandoned children. The Church's innovation, however, was the practice of oblation, whereby children were dedicated to lay life within monastic institutions and reared within a monastery. This created the first system in European history in which abandoned children were without legal, social, or moral disadvantage. As a result, many of Europe's abandoned and orphaned became alumni of the Church, which in turn took the role of adopter. Oblation marks the beginning of a shift toward institutionalization, eventually bringing about the establishment of the foundling hospital and orphanage.[7]

As the idea of institutional care gained acceptance, formal rules appeared about how to place children into families: boys could become apprenticed to an artisan and girls might be married off under the institution's authority.[7] Institutions informally adopted out children as well, a mechanism treated as a way to obtain cheap labor, demonstrated by the fact that when the adopted died, their bodies were returned by the family to the institution for burial.[7]

This system of apprenticeship and informal adoption extended into the nineteenth century, today seen as a transitional phase for adoption history. Under the direction of social welfare activists, orphan asylums began to promote adoptions based on sentiment rather than work, and children were placed out under agreements to provide care for them as family members instead of under contracts for apprenticeship.[10] The growth of this model is believed to have contributed to the enactment of the first modern adoption law in 1851 by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, unique in that it codified the ideal of the "best interests of the child."[10][11] Despite its intent, though, in practice, the system operated much the same as earlier incarnations. The experience of the Boston Female Asylum (BFA) is a good example, which had up to 30 percent of its charges adopted out by 1888.[10] Officials of the BFA noted that, although the asylum promoted otherwise, adoptive parents did not distinguish between indenture and adoption; "We believe," the asylum officials said, "that often, when children of a younger age are taken to be adopted, the adoption is only another name for service."[10]

Modern period

- Adopting to create a family

The next stage of adoption's evolution fell to the emerging nation of the United States. Rapid immigration and the aftermath of the American Civil War resulted in unprecedented overcrowding of orphanages and foundling homes in the mid-nineteenth century. Charles Loring Brace, a Protestant minister became appalled by the number of homeless children roaming the streets of New York City. Brace considered the abandoned youth, particularly Catholics, to be the most dangerous element challenging the city's order.[12]

His solution was outlined in The Best Method of Disposing of Our Pauper and Vagrant Children (1859) which started the Orphan Train movement. The orphan trains eventually shipped an estimated 200,000 children from the urban centers of the East to the nation's rural regions.[13] The children were generally indentured, rather than adopted, to families who took them in.[14]

The sheer size of the displacement—the largest migration of children in history—and the degree of exploitation that occurred, gave rise to new agencies and a series of laws that promoted adoption arrangements rather than indenture. The hallmark of the period is Minnesota's adoption law of 1917 which mandated investigation of all placements and limited record access to those involved in the adoption.[15][13]

During the same period, the Progressive movement swept the United States with a critical goal of ending the prevailing orphanage system. The culmination of such efforts came with the First White House Conference on the Care of Dependent Children called by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1909,[16] where it was declared that the nuclear family represented "the highest and finest product of civilization” and was best able to serve as primary caretaker for the abandoned and orphaned.[15][13]

Nevertheless, the popularity of eugenic ideas in America put up obstacles to the growth of adoption.[13][17] There were grave concerns about the genetic quality of illegitimate and indigent children, perhaps best exemplified by the influential writings of Henry H. Goddard who protested against adopting children of unknown origin:

Now it happens that some people are interested in the welfare and high development of the human race; but leaving aside those exceptional people, all fathers and mothers are interested in the welfare of their own families. The dearest thing to the parental heart is to have the children marry well and rear a noble family. How short-sighted it is then for such a family to take into its midst a child whose pedigree is absolutely unknown; or, where, if it were partially known, the probabilities are strong that it would show poor and diseased stock, and that if a marriage should take place between that individual and any member of the family the offspring would be degenerates.[18]

It took a war and the disgrace of Nazi eugenic policies to alter attitudes. The period from 1945 to 1974 saw rapid growth and acceptance of adoption as a means to build a family.[15] Illegitimate births rose three-fold after WWII, as sexual mores changed. Simultaneously, the scientific community began to stress the dominance of nurture over genetics, chipping away at eugenic stigmas.[19] In this environment, adoption became the obvious solution for both unwed mothers and infertile couples.[1]

Taken together, these trends resulted in a new American model for adoption. Following its Roman predecessor, Americans severed the rights of the original parents while making adopters the new parents in the eyes of the law. Two innovations were added: First, adoption was meant to ensure the "best interests of the child;" the seeds of this idea can be traced to the first American adoption law in Massachusetts.[4][11] Second, adoption became infused with secrecy, eventually resulting in the sealing of adoption and original birth records by 1945. The origin of the move toward secrecy began with Charles Loring Brace who introduced it to prevent children from the Orphan Trains from returning to or being reclaimed by their parents. Brace feared the impact of the parents' poverty, in general, and their Catholic religion, in particular, on the youth. This tradition of secrecy was carried on by the later Progressive reformers when drafting of American laws.[20]

The American model of adoption eventually proliferated globally. England and Wales established their first formal adoption law in 1926. The Netherlands passed its law in 1956. Sweden made adoptees full members of the family in 1959. West Germany enacted its first laws in 1977.[21] Additionally, Asian nations opened their orphanage systems to adoption.[13]

Contemporary Adoptions

Ironically, adoption is far more visible and discussed in society today, yet it is less common.[13] Many jurisdictions have different eligibility criteria for becoming an adoptive parent, and may specify such things as minimum and maximum age limits, whether a single person or only a couple can apply, or whether it is possible or not for a same sex couple to apply.

In some countries, applications must be made to a state agency or agencies responsible for adoption. There may also be private, licensed adoption agencies that may operate either on a commercial or on a non-profit basis. Agencies may operate only domestically, or may offer international adoptions, or may facilitate both. Some jurisdictions allow lawyers to arrange private adoptions, and some allow private facilitators to operate.

On applying to adopt, the potential adoptive parent(s) will generally be assessed for suitability. This can take the form of a home study, interviews, and financial, medical, and criminal record checks. In some jurisdictions, such studies must be carried out by an independent or state authority, while in others, they can be carried out by the adoption agency itself. A pre-adoption course may also be required.

Infants are more commonly sought than toddlers or older children, and many adoptive parents seek to adopt children of the same race. As a result, governments, as well as agencies, actively seek families who are interested in adopting older children, siblings, and children with special needs.

Forms of adoption

Contemporary adoption practices can be open or closed.

- Open adoption allows identifying information to be communicated between adoptive and biological parents and, perhaps, interaction between kin and the adopted person. Rarely, it is the outgrowth of laws that maintain an adoptee's right to unaltered birth certificates and/or adoption records, but such access is not universal.[22]

- The practice of closed adoption, the norm for most of modern history,[13] seals all identifying information, maintaining it as secret and barring disclosure of the identities of the adoptive parents, biological kins, and adoptees. Nevertheless, closed adoption may allow the transmittal of non-identifying information such as medical history and religious and ethnic background.[22]

- A third option of semi-open adoption is also possible. In this case a third party mediates the contact between adoptive and biological parents. This may or may not include contact.[22]

Cost of adoption

Adoption costs and assistance vary among countries. In many countries it is illegal to charge for an adoption, while in others adoptions must be facilitated on a non-profit basis. On the other hand many adoption programs will give financial assistance to adopters, especially with their expenses. Some jurisdictions offer tax credits to offset the cost of adoption. In the United States there has been a $10,000 tax credit for adoption of special needs children. Generally, in the United States, adoptions through the child welfare system do not cost the adopting family anything. The same is true in Canada.

Where there are charges for adoption there is often controversy, even in the case of non-profit agencies. Regulations may also specify to whom payments may or may not be made. For example, in some jurisdictions no money may be paid to a birth mother above her medical expenses.

International adoptions tend to be more expensive and often incur additional costs, as the adoptive parent(s) may be required to travel to the source country. Translation fees also apply to legal documents.

Issues surrounding adoption

Loss of Family Heritage

Preserving an adopted child's heritage has become a central issue in adoption in the United States and Europe. It has often been assumed that adopting babies at a very young age (1-2 months) bears no emotional consequences for the child. In the past, many adoption professionals believed that because most people have no recollection of their own birth, an adopted baby would not have a childhood any different from that which he would have had if he had been raised by his biological parents. However, while some adoptees do not feel that adoption has raised any special difficulties for them, others report that adoption has posed certain problems.

Work on openness in adoption has attempted to address these issues. Researchers such as Joyce Maguire Pavao,[23] Lois Ruskai Melina, [24] and others have advised all three sides of the adoption triad (birth parents, adoptive parents, and adoptees) on how to establish healthy relationships, and make it easier for adopted people to discuss their feelings and maintain meaningful contact with both biological and adoptive families. However, this is not the norm in most adoptions outside of foster care systems.

International adoptees face additional challenges. It has been argued that children adopted through international adoptions are best served when adoptive families commit to integrating various features of the child's birth nation, such as culture, traditions, stories, and language. Some countries now require adoptive parents to keep the birth names of their adoptive children, and many adoptive parents choose to do this to help their child develop a strong sense of self. However, in practice this can be very difficult to do in a meaningful way, especially for adoptive families who are not themselves experienced cross-culturally.

Mental Health

Research in brain development of infants and toddlers based on neuroscience and psychology disclosed much previously unknown information about the need for infants and toddlers to have very close attachment figures that provide consistent care, nurturing, and interaction. The primary caretaker might be the mother, father, grandparent, aunt, sister or any other totally devoted human being. This provides a different window of understanding into the emotional, social, cognitive, and physical needs of both adoptive parents and children.

However, there is no single answer to the matter of adoption; each case is unique. Many adopted children consider their adoptive parents to be their true caregivers and can easily adapt to the relationship. Later, they also are able to understand their relationship to their biological parents. In these cases, successful attachment and bonding has occurred in the adoptive family.

Many adoptions involve absent birth parents due to death, neglect, or other extenuating circumstances. At other times the adoption process is planned. Those children who lost their primary caregivers have a variety of separation issues to deal with depending on when it happened, whether it was from neglect and/or child abuse, how old the infant/child was when adoption took place and so forth.

Children with histories of maltreatment, such as physical and psychological neglect, physical abuse, and sexual abuse, are at risk of developing severe psychiatric problems,[25] [26] including Reactive attachment disorder (RAD).[27] [28] Abuse or neglect, inflicted by a primary caregiver, causes trauma which disrupts the normal development of secure attachment. Such children are at risk of developing a disorganized attachment.[27] [29] [30] Disorganized attachment is associated with a number of developmental problems, including dissociative symptoms,[31] as well as depressive, anxiety, and acting-out symptoms.[32] [33]

For all adopted people in adoptions where information about the family of origin is withheld, secrecy may disrupt the process of forming an identity. Family concerns regarding genealogy can be a source of confusion.[34] Another common concern is the lack of a medical history, which can affect the adopted person and also his or her subsequent children.

Adoption is problematic for some birthparents. When a parent chooses to place the child with adoptive parents, the process of separation can be difficult for all parties. Those emotional difficulties may carry on for many years past the date of the adoption, with families of origin missing and longing for the children they have placed.

Adoption may also pose lifelong difficulties for adoptive parents. Charting a course among the various schools of thought about openness, maintaining a child's connection to his or her family of origin, answering a child's difficult questions, and helping a child deal with birthparents who may not maintain regular contact are all issues that adoptive families may struggle with. For anyone involved in adoption—birthparent, adoptive parent, or adoptee—there are no hard and fast rules about how to build appropriate relationships that are in the child's best interest.

Honesty Issues

Some adoptees report that they were made to feel, consciously or not, as if they should forever be grateful to have been "chosen." This confuses children who otherwise felt very good about their adoptive families, and expected a relationship of unconditional love with their adoptive parents.

This kind of ambiguity in adoption, along with the emotionally charged nature of the subject, can make it difficult for adoptees to feel free to discuss their own concerns honestly, for fear of being ungrateful, hurting their adoptive parents' feelings, raising subjects they sense are taboo (such as the adoptive parents' true reasons for adopting, especially if this involves infertility) or incurring rejection.

Abuse, Neglect, and Carelessness

Some adoptive parents have shown less than normal interest in their children's well being. Several studies have indicated that parental neglect, carelessness, and abuse is dramatically higher for adopted children, the majority of whom are adopted through the child welfare system in the UK, Canada, and the U.S. As such, adopted children are much more likely to die prematurely than those raised in birth families, with increases in risk of death of as much as 65 times being reported.[35]

Where cases of adoptive family abuse especially in the child welfare or foster system have been uncovered, the public agencies involved have implemented efforts to curtail this kind of abuse such as strict requirements for background checks, home inspections, and required training.

Adoption in the Wake of Disasters

After disasters like hurricanes, tsunamis, and wars there is often an outpouring of offers from adults who want to give homes to the children left in need. While adoption is often the best way to provide stable, loving families for children in need, research suggests that adoption in the immediate aftermath of trauma or upheaval may not be the best option. Traumatized children need time to adjust, in the most familiar environments available, before they should be placed. Moving them too quickly into new adoptive homes among strangers may be a mistake: with time, it may turn out that the parents have survived but were unable to find the children, or there may be a relative or neighbor who can offer shelter and homes. Providing safety and emotional support may be better in those situations than relocation to a new adoptive family.[36] There is also an increased risk, immediately following a disaster, that displaced and/or orphaned children may be more vulnerable to exploitation and child trafficking.[37]

Adoption by Same-sex Couples

Certain jurisdictions prohibit homosexuals and bisexuals from adopting children, or have a policy of providing heterosexual adopters with adoptees before applications made by homosexuals are considered. The issue of adoption by homosexuals and bisexuals is tied in with the debate on homosexuality and same-sex marriage. From an international perspective, the culture and moral norms of the society play a role in considerations about adoption.

Adoption Reform

Two important influences on the reform of voluntary infant adoption have been Nancy Verrier and Florence Fischer. Verrier has described the "primal wound" as the "devastation which the infant feels because of separation from its natural mother. It is the deep and consequential feeling of abandonment which the baby adoptee feels after the adoption and which continues for the rest of his life."[38]

In some cases, however, the separation of the parent-child bond is necessary to protect the child. For children who have been neglected or abused, adoption is often necessary to ensure stability and the opportunity to bond with a new family in an emotionally healthy way. Where, in the past, neglected or abused children were often kept in foster care for many years while birthparents attempted to resolve issues of alcoholism, drug addiction, domestic violence, or mental illness, later theories of social work encourage government agencies to move quickly to free such children for adoption and to find them new, permanent homes. This philosophy is enshrined in the United States in the Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997, a law aimed at preventing foster care drift. By keeping children from bouncing from foster home to foster home, state agencies hope to preserve children's abilities to trust and attach, and hence to maintain and improve their mental health.

International Variations in Adoption

Adoption need not always entail assuming the title of "mother" and/or "father" to an orphaned child. Traditionally in Arab cultures if a child is adopted he or she does not become a “son” or “daughter,” but rather a "ward" of the adopting caretaker(s). The child’s family name is not changed to that of the adopting parent(s) and his or her “guardians” are publicly known as such. Legally, this is close to other nations' foster caring, but often with closer parental feelings.

In Korean culture, adoption almost always occurs when another family member (sibling or cousin) gives a male child to the first-born male heir of the family. Adoptions outside the family are rare. This is also true to varying degrees in other Asian societies.

On the other hand, in many African cultures, children are regularly exchanged among families for the purpose of adoption. By placing a child in another family's home, the birth family seeks to create enduring ties with the family that is now rearing the child. The placing family may receive another child from that family, or from another. Like the reciprocal transfer of brides from one family to another, these adoptive placements are meant to create enduring connections and social solidarity among families and lineages.

Islamic Countries

Islamic regulations regarding adoption are distinct from western practices and customs of adoption. Adoption in Islam is not forbidden, but naming an adopted son after his adopted father is not allowed if the child's biological father is known.

Islam also rejects the notion of an adopted child becoming a biological part of the family, hence, the adopted child is counted as a non-Mahram, where Mahram refers to an unmarriageable kin with whom sexual intercourse would be considered incestuous, a punishable taboo. However, this can be sidestepped by the child being nursed by the adoptive mother in the first half years of life.

An important fact to keep in mind is that Muhammad himself adopted a child, and Muhammad himself also was once given suck by an adoptive mother during the first two years of his life.

Relevant issues include the marriage between Zayd ibn Harithah's ex-wife and Muhammad, and also the narration involving Aisha's, Abu Hudaifah ibn Utbah and Salim mawla Abu Hudaifa.

Narrated Aisha:

(the wife of the Prophet) Abu Hudhaifa, one of those who fought the battle of Badr, with Allah's Apostle adopted Salim as his son and married his niece Hind bint Al-Wahd bin 'Utba to him' and Salim was a freed slave of an Ansari woman. Allah's Apostle also adopted Zaid as his son. In the Pre-lslamic period of ignorance the custom was that, if one adopted a son, the people would call him by the name of the adopted-father whom he would inherit as well, till Allah revealed: "Call them (adopted sons) By (the names of) their fathers." (33.5) [39]

United States

The United States 2000 census was the first in which adoption statistics were collected. The United States has a system of foster care by which adults care for minor children who are not able to live with their biological parents. Most children are placed for adoption through the foster care system. The enactment of the Adoption and Safe Families Act in 1997 approximately doubled the number of children adopted from foster care in the United States. In fiscal year 2001, 50,703 foster children were adopted in the United States, many by their foster parents or relatives of their biological parents.

Adoption agencies can range from government-funded agencies that place children at little cost, to lawyers who arrange private adoptions, to international commercial and non-profit agencies. Adoptive parents can pay from nothing to $40,000 for an adoption.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Barbara Melosh, Strangers and Kin: The American Way of Adoption (Harvard University Press, 2006, ISBN 0674019539).

- ↑ Code of Hammurabi. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ↑ Codex Justinianus. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 David M. Brodzinsky and Marshall D. Schechter (eds), The Psychology of Adoption (Oxford University Press, 1993, ISBN 0195082737).

- ↑ H. David Kirk, Adoptive Kinship: A Modern Institution in Need of Reform (Ben-Simon Publications, 1985, ISBN 0914539019).

- ↑ Mary Kathleen Benet, The Politics of Adoption (The Free Press, 1976, ISBN 0029025001).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 John Boswell, The Kindness of Strangers: The Abandonment of Children in Western Europe from Late Antiquity to the Renaissance (University Of Chicago Press, 1998, ISBN 0226067122).

- ↑ Vinita Bhargava, Adoption in India: Policies and Experiences (Sage Publications, 2005, ISBN 8178295172).

- ↑ Werner F. Menski, Comparative Law in a Global Context: The Legal Systems of Asia and Africa (Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0521675294).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Susan Porter, "A Good Home" in Adoption in America: Historical Perspectives edited by E. Wayne Carp (University of Michigan Press, 2004, ISBN 047203054X).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Ellen Herman, Timeline of Adoption History Adoption History Project, University of Oregon, Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ↑ Charles Loring Brace, The Dangerous Classes of New York and Twenty Years' Work Among Them (1880, General Books LLC, 2010, ISBN 978-1153661362).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 Ellen Herman, Kinship by Design: A History of Adoption in the Modern United States (University Of Chicago Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0226327600).

- ↑ Stephen O’Connor, Orphan Trains: The Story of Charles Loring Brace and the Children He Saved and Failed (University Of Chicago Press, 2004, ISBN 0226616673).

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 E. Wayne Carp (ed.) Adoption in America: Historical Perspectives (University of Michigan Press, 2004, ISBN 047203054X).

- ↑ Martin Gottlieb, The Foundling: The Story of the New York Foundling Hospital (Lantern Books, 2002, ISBN 1930051964).

- ↑ Jon Lawrence and Pat Starkey (eds.) Child Welfare and Social Action in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: International Perspectives (Liverpool University Press, 1991, ISBN 0853236763).

- ↑ Henry H. Goddard, "Wanted: A Child to Adopt" Survey (27) (October 14, 1911):1003-1006. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ↑ William D. Mosher and Christine A. Bachrach, "Understanding U.S. Fertility: Continuity and Change in the National Survey of Family Growth, 1988-1995", Family Planning Perspectives 28(1) (January/February 1996): 5. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ↑ E. Wayne Carp, Family Matters: Secrecy and Disclosure in the History of Adoption (Harvard University Press, 2000, ISBN 0674001869).

- ↑ Christine Adamec and William Pierce, The Encyclopedia of Adoption (Facts on File, 2000, ISBN 0816040419).

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Samantha Alkire, What’s the Difference Between Open, Semi-Open, And Closed Adoption? Adoption.org. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ↑ Joyce Maguire Pavao, The Family of Adoption (Beacon Press, 2005, ISBN 0807028274).

- ↑ Lois Ruskai Melina, Raising Adopted Children: Practical Reassuring Advice for Every Adoptive Parent (Collins, 1998, ISBN 0060957174).

- ↑ L. Gauthier, G. Stollak, L. Messe, and J. Arnoff, "Recall of childhood neglect and physical abuse as differential predictors of current psychological functioning," Child Abuse and Neglect 20(1996): 549-559.

- ↑ R. Malinosky-Rummell and D.J. Hansen, "Long term consequences of childhood physical abuse," Psychological Bulletin 114(1993): 68-69

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 K. Lyons-Ruth and D. Jacobvitz, "Attachment disorganization: unresolved loss, relational violence and lapses in behavioral and attentional strategies," in J. Cassidy & P. Shaver (eds.) Handbook of Attachment (New York: Guilford Press, 1999, 520-554).

- ↑ M. Greenberg, "Attachment and Psychopathology in Childhood" in J. Cassidy and P. Shaver (eds.) Handbook of Attachment (New York, NY: Guilford Press, 1999, 469-496).

- ↑ J. Solomon and C. George (eds.), Attachment Disorganization (New York: Guilford Press, 1999).

- ↑ M. Main and E. Hesse, "Parents’ Unresolved Traumatic Experiences are related to infant disorganized attachment status" in M.T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, and E. M. Cummings (eds), Attachment in the Preschool Years: Theory, Research, and Intervention (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1990, 161-184).

- ↑ E.A. Carlson, "A prospective longitudinal study of disorganized/disoriented attachment" Child Development 69(1988): 1107-1128.

- ↑ K. Lyons-Ruth, "Attachment relationships among children with aggressive behavior problems: The role of disorganized early attachment patterns," Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64(1996): 64-73.

- ↑ K. Lyons-Ruth, L. Alpern, and B. Repacholi "Disorganized infant attachment classification and maternal psychosocial problems as predictors of hostile-aggressive behavior in the preschool classroom," Child Development 64(1993): 572-585.

- ↑ Jennifer Strickler, Why Adoptive Parents Support Open Records for Adult Adoptees Bastard Nation, 1996. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ↑ Matt Ridley, The Red Queen: Sex and the Evolution of Human Nature (New York: Penguin Books, 1995, ISBN 0140245480).

- ↑ Adoption After a Disaster Officiel website on International Adoption in Québec Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ↑ Jedd Medefind, Human Trafficking & Orphans: The 2018 Trafficking in Persons Report Christian Alliance for Orphans, July 17, 2018. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ↑ Nancy Verrier, The Primal Wound: Understanding the Adoptive Child (Gateway Press, 1993, ISBN 0963648004).

- ↑ Issues Regarding Adoption in Islam AdoptIslam.co.uk. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adamec, Christine, and William Pierce. The Encyclopedia of Adoption. Facts on File, 2000. ISBN 0816040419

- Benet, Mary Kathleen. The Politics of Adoption. The Free Press, 1976. ISBN 0029025001

- Bhargava, Vinita. Adoption in India: Policies and Experiences. Sage Publications, 2005. ISBN 8178295172

- Boswell, John. The Kindness of Strangers: The Abandonment of Children in Western Europe from Late Antiquity to the Renaissance. University Of Chicago Press, 1998. ISBN 0226067122

- Brace, Charles Loring. The Dangerous Classes of New York and Twenty Years' Work Among Them. General Books LLC, 2010 (originally published 1880). ISBN 978-1153661362

- Brodzinsky, David M., and Marshall D. Schechter (eds). The Psychology of Adoption. Oxford University Press, 1993. ISBN 0195082737

- Carp, E. Wayne. Family Matters: Secrecy and Disclosure in the History of Adoption. Harvard University Press, 2000. ISBN 0674001869

- Carp, E. Wayne (ed.). Adoption in America: Historical Perspectives. University of Michigan Press, 2004. ISBN 047203054X

- Cassidy, Jude, and Phillip R. Shaver (Eds.). Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications. The Guilford Press, 1999. ISBN 1572308265

- Gottlieb, Martin. The Foundling: The Story of the New York Foundling Hospital. Lantern Books, 2002. ISBN 1930051964

- Greenberg, Mark T., Dante Cicchetti, and E. Mark Cummings (Eds.). University Of Chicago Press, 1993. ISBN 0226306305

- Herman, Ellen. Kinship by Design: A History of Adoption in the Modern United States. University Of Chicago Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0226327600

- Kirk, H. David. Adoptive Kinship: A Modern Institution in Need of Reform. Ben-Simon Publications, 1985. ISBN 0914539019

- Lawrence, Jon, and Pat Starkey (eds.). Child Welfare and Social Action in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: International Perspectives. Liverpool University Press, 1991. ISBN 0853236763

- Melina, Lois Ruskai. Raising Adopted Children: Practical Reassuring Advice for Every Adoptive Parent. Collins, 1998. ISBN 0060957174

- Melosh, Barbara. Strangers and Kin: The American Way of Adoption. Harvard University Press, 2006. ISBN 0674019539

- Menski, Werner F. Comparative Law in a Global Context: The Legal Systems of Asia and Africa. Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 0521675294

- O’Connor, Stephen. Orphan Trains: The Story of Charles Loring Brace and the Children He Saved and Failed. University Of Chicago Press, 2004. ISBN 0226616673

- Pavao, Joyce Maguire. The Family of Adoption. Beacon Press, 2005. ISBN 0807028274

- Ridley, Matt. The Red Queen: Sex and the Evolution of Human Nature. New York: Penguin Books, 1995. ISBN 0140245480

- Solomon, Judith, and Carol C. George (Eds.). Attachment Disorganization. The Guilford Press, 1999. ISBN 1572304804

- Verrier, Nancy. The Primal Wound: Understanding the Adoptive Child. Nancy Verrier, 1993. ISBN 0963648004

External links

All links retrieved June 15, 2023.

- Adopting.com Internet adoption resources.

- Adoption Agencies List An online adoption agency directory.

- Adopted Asian Americans Asian-Nation.

- Adoption News

- Origins Canada

- Adoption.com central location for general and specific adoption information

- Adoption Healing

- A How to for International Adoptions

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.