Istanbul

| Hagia Sophia | |

| Location in Turkey | |

| Overview | |

| Region | Marmara Region, Turkey |

| Province | Istanbul Province |

| Population | 15,029,231 (December 2017) |

| Area | 1,538,77 km² |

| Population density | 2,691/km² |

| Elevation | 100 m |

| Postal code | 34010 to 34850 and 80000 to 81800 |

| Area code | (+90) 212 (European side) (+90) 216 (Asian side) |

| Mayor | Mevlut Uysal (Justice and Development Party) |

| Governor | Hüseyin Avni Mutlu |

Istanbul (Turkish: İstanbul, Greek: Κωνσταντινούπολη, historically Byzantium and later Constantinople; see other names) is Turkey's most populous city, and its cultural and financial center. The city covers 25 districts of the Istanbul province. It is located at 41° N 29° E, on the Bosporus strait, and encompasses the natural harbor known as the Golden Horn, in the northwest of the country. It extends both on the European (Thrace) and on the Asian (Anatolia) side of the Bosporus, and is thereby the only metropolis in the world which is situated on two continents. In its long history, Istanbul (Constantinople) served as the capital city of the Roman Empire (330-395), the Byzantine Empire (395-1204 and 1261-1453), the Latin Empire (1204-1261), and the Ottoman Empire (1453-1922). The city was chosen as joint European Capital of Culture for 2010. The "Historic Areas of Istanbul" were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1985.

Names

The city of Istanbul has had many names through its history. Byzantium, Constantinople, and Stamboul are examples that may still be found in active use. Among others, it has been called New Rome or Second Rome, since the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great founded it on the site of the ancient Greek city of Byzantium as a second, and decidedly Christian, capital of the Roman Empire, in contrast to the still largely pagan Rome.[2] It has also been nicknamed "The City on Seven Hills" because the historic peninsula, the oldest part of the city, was built by Constantine on seven hills to match the seven hills of Rome. The hills are represented in the city coat of arms with seven mosques, one at the top of each hill. Another old nickname of Istanbul is Vasileousa Polis (Queen of Cities) due to its importance and wealth throughout the Middle Ages.

In an edict of March 28, 1930, the Turkish authorities officially requested foreigners to cease referring to the city with their traditional non-Turkish names (such as Constantinople) and to adopt İstanbul as the sole name also in the foreign languages.[3][4]

Geography

Istanbul is located in the north-west Marmara Region of Turkey. It encloses the southern Bosporus which places the city on two continents – the western portion of Istanbul is in Europe, while the eastern portion is in Asia. The city boundaries cover a surface area of 1,539 square kilometers, while the metropolitan region, or the Province of Istanbul, covers 6,220 square kilometers.

Climate

The city has a temperate-continental climate, with hot and humid summers; and cold, rainy and often snowy winters. Humidity is generally rather high. Yearly precipitation for Istanbul averages 870 mm. Snowfall is quite common, snowing for a week or two during the winter season, even heavy snows can occur. It is most likely to occur between the months of December and March. The summer months between June and September bring average daytime temperatures of 28 °C (82 °F). The warmest month is July with an average temperature of 23.2 °C (74 °F), the coldest is January with 5.4 °C (42 °F). The weather becomes slightly cooler as one moves toward eastern Istanbul. Summer is by far the driest season. The city is quite windy, having an average wind speed of 17 km/h (11 mph).

Geology

Istanbul is situated near the North Anatolian fault line, which runs from northern Anatolia to the Marmara Sea. Two tectonic plates, the African and the Eurasian, push against each other here. This fault line has been responsible for several deadly earthquakes in the region throughout history. In 1509, a catastrophic earthquake caused a tsunami which broke over the sea-walls of the city, destroying over 100 mosques and killing 10,000 people. An earthquake largely destroyed the Eyüp Sultan Mosque in 1766. The 1894 earthquake caused the collapse of many parts of the Grand Bazaar. A devastating earthquake in August 1999, left 18,000 dead and many more homeless.[5][6] In all of these earthquakes, the devastating effects are a result of the close settlement and poor construction of buildings. Seismologists predict another earthquake, possibly measuring 7.0 on the Richter scale, occurring before 2025.

History

Founding of Byzantium

Greek settlers of Megara colonized the area in 685 B.C.E. Byzantium—then known as Byzantion—takes its name from of King Byzas of Magara under whose leadership the site was reportedly settled in 667. The town became an important trading center due to its strategic location at the Black Sea's only entrance. It later conquered Chalcedon, across the Bosporus.

The city was besieged by Rome and suffered extensive damage in 196 C.E. Byzantium was rebuilt by the Roman Emperor Septimius Severus and quickly regained its previous prosperity, being temporarily renamed as Augusta Antonina by the emperor, in honor of his son.

The location of Byzantium attracted Constantine the Great in 324 after a prophetic dream was said to have identified the location of the city. The practical reason behind his move was probably Constantine's final victory over Licinius at the Battle of Chrysopolis on the Bosporus, on September 18, 324, which ended the civil war between the Roman co-emperors, and brought an end to the final vestiges of the system in which Nicomedia (present-day İzmit, 100 km east of Istanbul) was the most senior Roman capital city.

Byzantium now called as Nova Roma and eventually Constantinopolis, was officially proclaimed the new capital of the Roman Empire six years later, in 330. Following the death of Theodosius I in 395 and the permanent partition of the Roman Empire between his two sons, Constantinople became the capital of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire. The unique position of Constantinople at the center of two continents made the city a magnet for international commerce, culture and diplomacy.

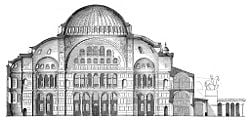

The Byzantine Empire was distinctly Greek in culture and became the center of Greek Orthodox Christianity. The capital was adorned with many magnificent churches, including the Hagia Sophia, once the world's largest cathedral. The seat of the Patriarch of Constantinople, spiritual leader of the Eastern Orthodox Church, still remains in the Fener (Phanar) district of Istanbul.

Orthodox and Catholic Christianity permanently split from one another in 1054 amid serious animosity. In 1204, the Fourth Crusade was launched to capture Jerusalem, but instead turned on Constantinople, which was sacked and desecrated. The city subsequently became the center of the Catholic Latin Empire, created by the crusaders to replace the Orthodox Byzantine Empire, which was divided into a number of splinter states. One of these, the Empire of Nicaea was to recapture Constantinople in 1261 under the command of Michael VIII Palaeologus.

Ottoman conquest

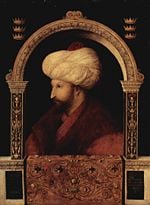

Following centuries of decline, Constantinople became surrounded by more youthful and powerful empires, most notably that of the Ottoman Turks. On 29 May 1453, Sultan Mehmed II "the Conqueror" entered Constantinople after a 53–day siege and the city was promptly made the new capital of the Ottoman Empire. The last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI (Palaeologus), was killed in battle. For three days the city was abandoned to pillage and massacre, after which order was restored by the sultan.

In the last decades of the Byzantine Empire, the city had decayed as the Byzantine state became increasingly isolated and financially bankrupt; its population had dwindled to some 30,000-40,000 people, while large sections remained uninhabited. Thus, Sultan Mehmed set out to rejuvenate the city economically, creating the Grand Bazaar and inviting the fleeing Orthodox and Catholic inhabitants to return back. Captured prisoners were freed to settle in the city while provincial governors in Rumelia and Anatolia were ordered to send 4,000 families to settle in the city, whether Muslim, Christian or Jew, to form a unique cosmopolitan society.[7] The Sultan also endowed the city with various architectural monuments, including the Topkapı Palace and the Eyüp Sultan Mosque. Religious foundations were established to fund the construction of grand imperial mosques, adjoined by their associated schools, hospitals and public baths.

Suleiman the Magnificent’s reign was a period of great artistic and architectural achievements. The famous architect Sinan designed many mosques and other grand buildings in the city, while Ottoman arts of ceramics and calligraphy also flourished. Many of these survive to this day; some in the form of mosques while others have become museums such as the Cerrahi Tekke and the Sünbül Efendi and Ramazan Efendi Mosques and Türbes; the Galata Mevlevihanesi; the Yahya Efendi Tekke; and the Bektaşi Tekke, which now serves Alevi Muslims as a cemevi (gathering house).

The city was modernized from the 1870s onwards with the construction of bridges, the creation of an updated water system, electric lights, and the introduction of streetcars and telephones.

Modern Istanbul

When the Republic of Turkey was founded in 1923, the capital was moved from Istanbul to Ankara. In the early years of the republic, Istanbul was overlooked in favor of the new capital. However, in the 1950s, Istanbul underwent great structural change, as new roads and factories were constructed throughout the city. Wide modern boulevards, avenues and public squares were built, sometimes at the expense of the demolition of historical buildings. The city's once numerous and prosperous Greek community, remnants of the city's Greek origins, dwindled in the aftermath of the 1955 Istanbul Pogrom, with most Greeks in Turkey leaving their homes for Greece.

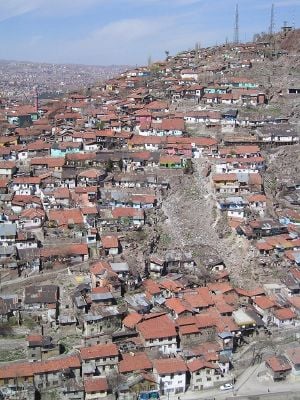

During the 1970s, the population of Istanbul began to rapidly increase as people from Anatolia migrated to the city in order to find employment in the many new factories that were constructed at the outskirts of the city. This sudden sharp increase in the population caused a rapid rise in housing development, some of poor quality, and many previously outlying villages became engulfed into the greater metropolis of Istanbul.

Today, as well as being the country's largest city, Istanbul is the financial, cultural, and economic center of modern Turkey.

Cityscape

Architecture

Throughout its long history, Istanbul has acquired a reputation for being a cultural and ethnic melting pot. As a result, there are many historical mosques, churches, synagogues, palaces, castles, and towers to visit in the city.

The most important monuments of Roman architecture include the Column of Constantine (Turkish: Çemberlitaş) which was erected in 330 C.E. and reportedly contains several fragments of the Original Cross and the bowl with which Virgin Mary washed the feet of Jesus at its base; the Mazulkemer Aqueduct and Valens Aqueduct; the Column of the Goths (Gotlar Sütunu) at the Seraglio Point; the Milion which served for calculating the distances between Constantinople and other cities of the Roman Empire; and the Hippodrome of Constantinople, which was built following the model of the Circus Maximus in Rome.

The city walls had 55 gates, the largest of which was the Porta Aurea (Golden Gate), the ceremonial entrance gate used by the emperors, at the southwestern end of the triple land walls, close to the Sea of Marmara. Unlike the city walls, which were built of brick and limestone, the Porta Aurea was built of large clean-cut white marble blocks in order to distinguish it from the rest, and a quadriga[8]with elephant statues stood on its top. The doors of the Porta Aurea were made of gold, hence the name, which means Golden Gate in Latin.

Early Byzantine architecture followed the classical Roman model of domes and arches, but further improved these architectural concepts, as evidenced with the Hagia Sophia, which was designed by Isidorus and Anthemius between 532 and 537 during the reign of Justinian the Great.

Many churches with magnificent golden icons were built until the eighth century. Many of these were vandalized during the iconoclasm movement of (730-787) which began with the reign of Leo III the Isaurian. The iconoclasts of this period, like the Muslim counterparts, believed that the images of Christ and other saints on the walls of the churches constituted a sin, and they forcefully had them removed or destroyed. A second iconoclastic period followed in (814-842), initiated by Leo V the Armenian.

During the Fourth Crusade in 1204, most of the city's important buildings were sacked by the forces of Western Christianity, and numerous architectural and artistic treasures were shipped to Venice, whose ruler, Enrico Dandolo, had organized the sack of Constantinople. These items include the famous Statue of the Tetrarchs and the four bronze horse statues that once stood at the top of the Hippodrome of Constantinople, which today stand on the front facade of the Saint Mark's Basilica in Venice.

The Palace of Porphyrogenitus (Turkish: Tekfur Sarayı), which is the only surviving part of the Blachernae Palace, dates from the period of the Fourth Crusade. In these years, on the northern side of the Golden Horn, the Dominican priests of the Catholic Church built the Church of Saint Paul in 1233.

Following the Ottoman conquest of the city, Sultan Mehmed II initiated a wide scale reconstruction plan, which included the construction of grand buildings such as the Eyüp Sultan Mosque, Fatih Mosque, Topkapı Palace, The Grand Bazaar and the Yedikule (Seven Towers) Castle which guarded the main entrance gate of the city, the Porta Aurea (Golden Gate). In the centuries following Mehmed II, many new important buildings, such as the Süleymaniye Mosque, Sultanahmet Mosque, Yeni Mosque and numerous others were constructed.

Traditionally, Ottoman buildings were built of ornate wood. Only "state buildings" such as palaces and mosques were built of stone. Starting from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, wood was gradually replaced with stone as the primary building material, while traditional Ottoman architectural styles were replaced with European architectural styles. New palaces and mosques were built in Neoclassical, Baroque and Rococo styles, or a mixture of all three, such as the Dolmabahçe Palace, Dolmabahçe Mosque and Ortaköy Mosque. Even Neo-Gothic mosques were built, such as the Pertevniyal Valide Sultan Mosque and Yıldız Mosque. Large state buildings like schools or military barracks were also built in various European styles.

Urbanism

In the last decades, numerous tall structures were built around the city to accommodate a rapid growth in population. Surrounding towns were absorbed into Istanbul as the city rapidly expanded outwards. The tallest high-rise office and residential buildings are mostly located in the northern areas of the European side, which also have numerous upmarket shopping malls.

Starting from the second half of the twentieth century, the Asian side of Istanbul, which was originally a tranquil place full of seaside summer residences and elegant chalet mansions surrounded by lush and vast umbrella pine gardens, experienced massive urban growth.

An improved transportation infrastructure, with both high speed highways and railways, encouraged this growth. Another important factor in the recent growth of the Asian side of the city has been migration from Anatolia. Today, more than one-third of the city's population live in the Asian side of Istanbul.

Due to Istanbul's exponential growth during the second half of the twentieth century, a significant portion of the city's outskirts consist of gecekondus, a Turkish word created in the 1940s meaning "built overnight." These neighborhoods are typically built on abandoned land or on lands owned by others, without the permission of the landowner, and do not obey building codes and regulations. At present, gecekondu areas are being gradually demolished and replaced by modern mass-housing complexes.

Administration

Organization

The metropolitan model of governance has been used with the establishment of metropolitan administration in 1930. The metropolitan council is accepted as the competent authority for decision-making. The metropolitan government structure consists of three main organs: (1) The Metropolitan Mayor (elected every five years), (2) The Metropolitan Council (decision making body with the mayor, district Mayors, and one fifth of the district municipal councilors), (3) The metropolitan executive committee. There are three types of local authorities: municipalities, special provincial administrations, and village administrations. Among the local authorities, municipalities are gaining greater importance with the rise in urbanization.

Istanbul has 31 districts. These can be divided into three main areas: the historic peninsula, the areas north of the Golden Horn, and the Asian side.

Demographics

The population of the metropolis has more than tripled during the 25 years between 1980 and 2005. Roughly 70 percent of all Istanbulers live in the European section and around 30 percent live in the Asian section. The doubling of the population of Istanbul between 1980 and 1985 is due to a natural increase in population as well as the expansion of municipal limits.

Religion

The urban landscape of Istanbul is shaped by its many religious communities. The most populous religion is Islam. Istanbul was the final seat of the Islamic Caliphate, between 1517 and 1924. The supposed personal belongings of the prophet Muhammad and the earliest Caliphs who followed him are today preserved in the Topkapı Palace, the Eyüp Sultan Mosque and in several other prominent mosques of Istanbul. Religious minorities include Greek Orthodox Christians, Armenian Christians, Catholic Levantines and Sephardic Jews. Some districts have sizable populations of these ethnic groups.

Following the Turkish conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the various ethnic groups were to be governed by a group of institutions based on faith. Many of the internal affairs of these communities were assigned to the administration of their religious authorities, such as the Ecumenical Patriarchate for the affairs of Orthodox Christians, the Armenian Patriarchate for the affairs of the Armenian Christians, and later the Grand Rabbi for the affairs of the Jews.

The population of the Armenian and Greek minorities in Istanbul greatly declined beginning in the late nineteenth century. The city's Greek Orthodox community were exempted from the population exchange between Greece and Turkey of 1923. However, a series of special restrictions and taxes beginning in the 1930s, finally culminating in the Istanbul Pogrom of 1955, greatly increased emigration; and in 1964, all Greeks without Turkish citizenship residing in Turkey (around 100,000) were deported. Today, most of Turkey's remaining Greek and Armenian minorities live in or near Istanbul.

The Sephardic Jews have lived in the city for over 500 years, see the history of the Jews in Turkey. Together with the Arabs, the Jews fled the Iberian Peninsula during the Spanish Inquisition of 1492, when they were forced to convert to Christianity after the fall of the Moorish Kingdom of Andalucia. The Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II (1481-1512) sent a sizable fleet to Spain under the command of Kemal Reis to rescue Arabs and Jews who faced torture and death because of their faith. More than 200,000 Spanish Jews fled first to locations such as Tangier, Algiers, Genova and Marseille, later to Salonica, and finally to Istanbul. The Sultan granted Ottoman citizenship to over 93,000 of these Spanish Jews. Another large group of Sephardic Jews came from southern Italy, which was under Spanish control. The first Gutenberg press in Istanbul was established by the Sephardic Jews in 1493, who excelled in many areas, particularly medicine, trade and banking. More than 20,000 Jews still remain in Istanbul today.

There is also a relatively smaller and more recent community of Ashkenazi (northern European) Jews in Istanbul who continue to live in the city since the nineteenth century. A second large wave of Ashkenazi Jews came to Istanbul during the 1930s and 1940s following the rise of Nazism in Germany which persecuted the Ashkenazi Jews of central and eastern Europe.

During the Byzantine period, the Genoese Podestà ruled over the Italian community of Galata, which was mostly made up of the Genoese, Venetians, Tuscans and Ragusans. Following the Turkish siege of Constantinople in 1453, during which the Genoese sided with the Byzantines and defended the city together with them, the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II allowed the Genoese (who had fled to their colonies in the Aegean Sea such as Lesbos and Chios) to return back to the city.

There were more than 40,000 Catholic Italians in Istanbul at the turn of the twentieth century, a figure which not only included the descendants of the local Genoese and Venetian merchants who lived there since the Byzantine and early Ottoman periods, but also the numerous Italian workers and artisans who came to the city from southern Italy during the nineteenth century.

The number of Istanbul's Italians decreased after the end of the Ottoman Empire for several reasons. The Turkish Republic no longer recognized the trade privileges that were given to the descendants of the Genoese and Venetian merchants, and foreigners were no longer allowed to work in Turkey in a wide number of sectors, including many artisanships, in which numerous Istanbulite Italians used to work. The Varlık Vergisi (Wealth Tax) of the World War II years, which imposed higher tariffs on non-Muslims and foreigners in Turkey, also played an important role in the migration of Istanbul's Italians to Italy - some, who still live in the city, but in far fewer numbers when compared with the early twentieth century. The influence of the Italian community of Istanbul, however, is still visible in the architecture of many quarters, particularly Galata, Beyoğlu and Nişantaşı.

Economy

Historically, Istanbul has been the center of the country's economic life due to its location as an international junction of land and sea trade routes. In 2005 the City of Istanbul had a GDP of $133 billion, outranking many prominent cities in the world.

In the late 1990s, the economy of Turkey, and Istanbul in particular, suffered several major depressions. The Asian financial crisis between July 1997 and the beginning of 1998, as well as the crisis in Russia between August 1998 and the middle of 1999 had negative effects in all areas of the economy, particularly on exports. Following this setback, a slow reorganization of the economy of Istanbul was observed in 1999.

The major earthquake with its epicenter in nearby Kocaeli on August 17, 1999, triggered one of the largest economic shocks for the city. Apart from the capital and human losses caused by the disaster, a decrease in GDP of approximately two percent occurred. Despite these downturns, Istanbul's economy has strongly improved and recovered in the recent years.

Industry

Istanbul is the "industrial center" of Turkey. It employs approximately 20 percent of Turkey's industrial labor and contributes 38 percent of Turkey's industrial workspace. In addition, the city generates 55 percent of Turkey's trade and 45 percent of the country's wholesale trade, and generates 21.2 percent of Turkey's gross national product. Istanbul contributes 40 percent of all taxes collected in Turkey and produces 27.5 percent of Turkey's national product.

Many of Turkey's major manufacturing plants are located in the city. Istanbul and its surrounding province produce cotton, fruit, olive oil, silk, and tobacco. Food processing, textile production, oil products, rubber, metal ware, leather, chemicals, electronics, glass, machinery, paper and paper products, and alcoholic drinks are among the city's major industrial products. The city also has plants that assemble automobiles and trucks.

Pharmaceutical industry started in 1952 with the establishment of "Eczacıbaşı Pharmaceuticals Factory" in Levent, Istanbul.[9] Today, 134 companies operate in the Turkish pharmaceutical industry, a significant part of which is based within or near Istanbul.[10]

Tourism

Istanbul is one of the most important tourism spots of Turkey. There are thousands of hotels and other tourist oriented industries in the city, catering to both vacationers and visiting professionals. In 2006 a total of 23 million tourists visited Turkey, most of whom entered the country through the airports and seaports of Istanbul and Antalya.[11]

Istanbul is also one of the world’s most exciting conference destinations and is an increasingly popular choice for the world’s leading international associations.

Infrastructure

Health and medicine

The city has many public and private hospitals, clinics and laboratories within its boundaries and numerous medical research centers. Many of these facilities have high technology equipment, which has contributed to the recent upsurge in "medical tourism" to Istanbul, [12]particularly from West European countries like the United Kingdom and Germany where governments send patients with lower incomes to the city for the relatively inexpensive service of high-tech medical treatment and operations. Istanbul has particularly become a global destination for laser eye surgery and plastic surgery. The city also has an Army Veterans Hospital in the military medical center.

Pollution-related health problems increase especially in the winter, when use of heating fuels increase. The rising number of new cars in the city and the slow development of public transportation often cause urban smog conditions. Mandatory use of unleaded gas was scheduled to begin only in January 2006.

Utilities

The first water supply systems which were built in Istanbul date back to the foundation of the city. Two of the greatest aqueducts built in the Roman period are the Mazulkemer Aqueduct and the Valens Aqueduct. These aqueducts were built in order to channel water from the Halkalı area in the western edge of the city to the Beyazıt district in the city center, which was known as the Forum Tauri in the Roman period. After reaching the city center, the water was later collected in the city's numerous cisterns, such as the famous Philoxenos (Binbirdirek) Cistern and the Basilica (Yerebatan) Cistern. Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent commissioned Sinan, his engineer and architect-in-chief, to improve the water needs of the city. Sinan constructed the Kırkçeşme Water Supply System in 1555. In later years, with the aim of responding to the ever-increasing public demand, water from various springs was channeled to the public fountains by means of small supply lines.

Today, Istanbul has a chlorinated and filtered water supply and a sewage disposal system managed by the government agency ISKI. The current level of facilities, however, is not sufficient enough to meet the rising demand of the growing city. Water supply sometimes becomes a problem, particularly in the summer.

Electricity distribution services are covered by the state-owned TEK. The first electricity production plant in the city, Silahtarağa Termik Santrali, was established in 1914 and continued to supply electricity until 1983.

The Ottoman Ministry of Post and Telegraph was established in the city on October 23, 1840. The first post office was the Postahane-i Amire near the courtyard of Yeni Mosque. In 1876 the first international postal network between Istanbul and the lands beyond the vast Ottoman Empire was established.[13]

Samuel Morse received his first ever patent for the telegraph in 1847, at the old Beylerbeyi Palace (the present Beylerbeyi Palace was built in 1861-1865 on the same location) in Istanbul, which was issued by Sultan Abdülmecid who personally tested the new invention.[14] Following this successful test, installation works of the first telegraph line between Istanbul and Edirne began on August 9, 1847. In 1855 the Telegraph Administration was established. In July 1881 the first telephone circuit in Istanbul was established between the Ministry of Post and Telegraph in Soğukçeşme and the Postahane-i Amire in Yenicami. On October 23, 1986, mobile telephone and paging systems were put into service in Istanbul, Ankara and İzmir. On February 23, 1994, GSM technology was established in the city. A nationwide Internet network and connection with the World Wide Web was established in 1996.

Infrastructure improvements since the mid 1990s include the resolution of the garbage problem, improved traffic conditions and improved air quality due to the increased use of natural gas.

Transportation

Istanbul has two international airports: The larger one is the Atatürk International Airport located in the Yeşilköy district on the European side, about 24 kilometers west from the city center. When it was first built, the airport used to be at the western edge of the metropolitan area but now lies within the city bounds.

The smaller one is the Sabiha Gökçen International Airport located in the Kurtköy district on the Asian side, close to the Istanbul Park GP Racing Circuit. It is situated approximately 20 kilometers east of the Asian side and 45 kilometers east of the European city center.

The Sirkeci Terminal of the Turkish State Railways (TCDD) is the terminus of all the lines on the European side and the main connection node of the Turkish railway network with the rest of Europe. Currently, international connections are provided by the line running between Istanbul and Thessaloniki, Greece, and the Bosporus Express serving daily between Sirkeci and Gara de Nord in Bucharest, Romania. Lines to Sofia, Belgrade, Budapest, and Chişinău are established over the Bosporus Express connection to Bucharest. Sirkeci Terminal was originally opened as the terminus of the Orient Express.

Sea transport is vital for Istanbul, as the city is practically surrounded by sea on all sides: the Sea of Marmara, the Golden Horn, the Bosporus and the Black Sea. Many Istanbulers live on the Asian side of the city but work on the European side (or vice-versa) and the city's famous commuter ferries form the backbone of the daily transition between the two parts of the city - even more so than the two suspension bridges which span the Bosporus.

The port of Istanbul is the most important one in the country. The old port on the Golden Horn serves primarily for personal navigation, while Karaköy port in Galata is used by the large cruise liners. Istanbul Modern, the city's largest museum and gallery of modern arts, is located close to Karaköy port.

Life in the city

Art & culture

Istanbul is becoming increasingly colorful in terms of its rich social, cultural, and commercial activities. While world famous pop stars fill stadiums, activities like opera, ballet and theater continue throughout the year. During seasonal festivals, world famous orchestras, chorale ensembles, concerts and jazz legends can be found often playing to a full house. Istanbul Archeology Museum, established in 1881, is one of the largest and most famous museums of its kind in the world. The museum contains more than 1,000,000 archaeological pieces from the Mediterranean basin, the Balkans, the Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia.

A significant culture has been developed around what is known as a Turkish Bath (Hamam), the origins of which can be traced back to the ancient Roman Bath, which was a part of the Byzantine lifestyle and customs that were inherited first by the Seljuk Turks and later the Ottomans, who developed it into something more elaborate.

Media

The first Turkish newspaper, Takvim-i Vekayi, was printed on 1 August 1831 in the Bâbıâli (Bâb-ı Âli, meaning The Sublime Porte) district. Bâbıâli became the main center for print media. Istanbul is also the printing capital of Turkey with a wide variety of domestic and foreign periodicals expressing diverse views, and domestic newspapers are extremely competitive. Most nationwide newspapers are based in Istanbul, with simultaneous Ankara and İzmir editions. There are also numerous local and national TV and radio stations located in Istanbul.

Education

Istanbul holds some of the finest institutions of higher education in Turkey, including a number of public and private universities. Most of the reputable universities are public, but in recent years there has also been an upsurge in the number of private universities. Istanbul University (1453) is the oldest Turkish educational institution in the city, while Istanbul Technical University (1773) is the world's second-oldest technical university dedicated entirely to engineering sciences. Other prominent state universities in Istanbul are the Boğaziçi University (1863), Mimar Sinan University of Fine Arts (1882), Marmara University (1883), Yıldız Technical University (1911) and Galatasaray University (1992).

Almost all Turkish private high schools and universities in Istanbul teach in English, German or French as the primary foreign language, usually accompanied by a secondary foreign language.

Sports

The first modern sports club established during the late Ottoman period was Beşiktaş Jimnastik Kulübü (1903). Beşiktaş JK was followed by Galatasaray SK (1905) and Fenerbahçe SK (1907). Galatasaray became the first Turkish football club to win European titles (the UEFA Cup and UEFA Super Cup of 2000). At present, Galatasaray is also the Turkish team with the most Turkish Super League titles (16) along with Fenerbahçe (16); followed by Beşiktaş (12) and Trabzonspor (6).

The Atatürk Olympic Stadium is a five-star UEFA stadium and a first-class venue for track and field, having reached the highest required standards set by the International Olympic Committee and sports federations such as the IAAF, FIFA and UEFA. The stadium hosted the 2005 UEFA Champions League Final.

Istanbul hosts several annual motorsports events, such as the Formula One Turkish Grand Prix, the MotoGP Grand Prix of Turkey, the FIA World Touring Car Championship, the GP2 and the Le Mans Series 1000 km races at the Istanbul Park GP Racing Circuit.

Notes

- ↑ The Results of Address Based Population Registration System, 2017 Turkish Statistical Institute, February 1, 2018. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ↑ Richard Krautheimer, Three Christian Capitals: Topography and Politics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987).

- ↑ Stanford J. Shaw and K. Ezel, History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. II. 1977), 386.

- ↑ Richard D. Robinson, The First Turkish Republic (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1965), 298.

- ↑ "Istanbul advised to brace for major quake." Environmental News Network via CNN, April 28, 2000. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ↑ T. Parsons, et al., "Heightened odds of large earthquakes near Istanbul: An interaction-based probability calculation." Science, 288(5466) (April 28, 2000): 61-65. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ↑ John Balfour Kinross, The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire (New York: Vintage/Ebury (A Division of Random House Group), [1977] 1997), 117

- ↑ A two-wheeled chariot drawn by four horses harnessed abreast.

- ↑ Baytop T. Türk Eczacılık Tarihi Araştırmaları (History of Turkish Pharmacy Researches) Istanbul. 2000:12-75.

- ↑ Dogan UVEY*, Ayse Nur GOKCE*, Ibrahim BASAGAOGLU (2004) "Pharmaceutical Industry in Turkey" in 38th International Medical History Congress in Istanbul.

- ↑ Hürriyet Haber, Hürriyet: 2006’da Türkiye’ye gelen turist başına harcama 728 dolara indi. www.hurriyet.com.tr, January 31, 2007. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ↑ Med Retreat - Medical Tourism: Turkey. www.medretreat.com. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ↑ ISTANBUL, Extended On Two Continents. İstanbul PTT Museum, July 22, 2017. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ↑ Mansions and Palaces: Beylerbeyi Palace. Istanbul City Guide. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Freely, John. Istanbul: The Imperial City. Penguin Books, 1996. ISBN 978-0140244618

- Kinross, John Balfour. The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire. Vintage/Ebury (A Division of Random House Group), 1977. ISBN 978-0224013796

- Krautheimer, Richard. Three Christian Capitals: Topography and Politics. University of California Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0520060340

- Robinson, Richard D. The First Turkish Republic. Harvard University Press, 1963. ISBN 978-0674304505

- Shaw, Stanford J. and K. Ezel. History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. II, 1977. ISBN 978-0521291668

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

.jpg/300px-Mimar_Sinan_-_Mosquée_Şehzade_Mehmet%2C_Istanbul_(02).jpg)

.jpg/250px-Arnavutköy%2C_Bebek_Arnavutköy_Cd_No-115%2C_34345_Beşiktaş-İstanbul%2C_Turkey_-_panoramio_(3).jpg)

_-_San_Gregorio_armeno_-_Foto_G._Dall%27Orto_26-5-2006.jpg/250px-Istanbul_-_Chiesa_Pammacaristos_(Fetiye_camii)_-_San_Gregorio_armeno_-_Foto_G._Dall%27Orto_26-5-2006.jpg)