James Dean

| James Dean | |

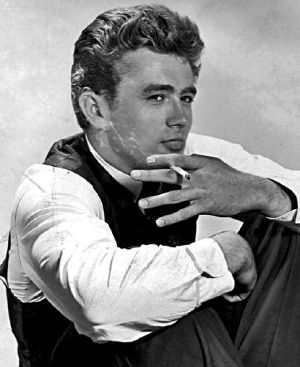

Dean in 1955

| |

| Born | James Byron Dean February 8 1931 Marion, Indiana, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Died | September 30 1955 (aged 24) Cholame, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Car accident |

| Resting place | Park Cemetery, Fairmount, Indiana, U.S. |

| Education | Santa Monica College UCLA |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1950–1955 |

| Signature | |

| Website jamesdean.com | |

James Byron Dean (February 8, 1931 - September 30, 1955) was an American actor. He is remembered as a cultural icon of teenage disillusionment and social estrangement, as expressed in the title of his most celebrated film, Rebel Without a Cause (1955), in which he starred as troubled teenager Jim Stark. The other two roles that defined his stardom were loner Cal Trask in East of Eden (1955) and surly ranch hand Jett Rink in Giant (1956).

After his death in a car crash on September 30, 1955, Dean became the first actor to receive a posthumous Academy Award nomination for Best Actor for his role in East of Eden. Upon receiving a second nomination for his role in Giant the following year, Dean became the only actor to have had two posthumous acting nominations. American teenagers of the mid-1950s, when Dean's major films were first released, identified with Dean and the roles he played. Many decades after his death, Dean's legacy remains as an icon of adolescent angst and rebellion.

Early life and education

James Byron Dean was born on February 8, 1931, at the Seven Gables apartment on the corner of 4th Street and McClure Street in Marion, Indiana,[1] the only child of Mildred Marie (Wilson) and Winton Dean. He also claimed that his mother was partly Native American, and that his father belonged to a "line of original settlers that could be traced back to the Mayflower.[2]

Six years after his father had left farming to become a dental technician, Dean moved with his family to Santa Monica, California. He was enrolled at Brentwood Public School in the Brentwood neighborhood of Los Angeles, California, but transferred soon afterward to the McKinley Elementary School.[3] The family spent several years there, and by all accounts, Dean was very close to his mother. According to Michael DeAngelis, she was "the only person capable of understanding him."[4] In 1938, she was suddenly struck with acute stomach pain and quickly began to lose weight. She died of uterine cancer when Dean was nine years old.[3] Unable to care for his son, Dean's father sent him to live with his aunt and uncle, Ortense and Marcus Winslow, on their farm in Fairmount, Indiana,[5] where he was raised in their Quaker household.[6] Dean's father served in World War II and later remarried.

In his adolescence, Dean sought the counsel and friendship of a local Methodist pastor, the Rev. James DeWeerd, who seems to have had a formative influence upon Dean, especially upon his future interests in bullfighting, car racing, and theater.[7] According to Billy J. Harbin, Dean had "an intimate relationship with his pastor, which began in his senior year of high school and endured for many years."[8] Their alleged sexual relationship was suggested in Paul Alexander's 1994 book Boulevard of Broken Dreams: The Life, Times, and Legend of James Dean.[9] Elizabeth Taylor reported that Dean once confided in her that he was sexually abused by a minister approximately two years after his mother's death.[10] Hyams also provides an account alleging Dean's molestation as a teenager by his early mentor DeWeerd and describe it as Dean's first homosexual encounter (although DeWeerd himself largely portrayed his relationship with Dean as a completely conventional one).[11]

Dean's overall performance in school was exceptional and he was a popular student. He played on the baseball and varsity basketball teams, studied drama, and competed in public speaking through the Indiana High School Forensic Association. After graduating from Fairmount High School in May 1949, he moved back to California with his dog, Max, to live with his father and stepmother. He enrolled in Santa Monica College (SMC) and majored in pre-law. He transferred to UCLA for one semester and changed his major to drama,[12] which resulted in estrangement from his father. While at UCLA, Dean was picked from a group of 350 actors to portray Malcolm in Macbeth.[13] At that time, he also began acting in James Whitmore's workshop. In January 1951, he dropped out of UCLA to pursue a full-time career as an actor.

Acting career

Early career

Dean's first television appearance was in a Pepsi Cola commercial.[14][15] He quit college to act full-time and was cast in his first speaking part, as John the Beloved Disciple in Hill Number One, an Easter television special dramatizing the Resurrection of Jesus.[16] Dean subsequently obtained three walk-on roles in movies: as a soldier in Fixed Bayonets! (1951), a boxing cornerman in Sailor Beware (1952),[17] and a youth in Has Anybody Seen My Gal? (1952).[18]

While struggling to gain roles in Hollywood, Dean also worked as a parking lot attendant at CBS Studios, during which time he met Rogers Brackett, a radio director for an advertising agency, who offered him professional help and guidance in his chosen career, as well as a place to stay.[19][11] Brackett opened doors for Dean and helped him land his first starring role on Broadway in See the Jaguar, a flop that closed after five performances.

In July 1951, Dean appeared on Alias Jane Doe, which was produced by Brackett.[12][11] In October 1951, following the encouragement of actor James Whitmore and the advice of his mentor Rogers Brackett, Dean moved to New York City. There, he worked as a stunt tester for the game show Beat the Clock, but was subsequently fired for allegedly performing the tasks too quickly.[2] He also appeared in episodes of several CBS television series The Web, Studio One, and Lux Video Theatre, before gaining admission to the Actors Studio to study method acting under Lee Strasberg.[14] In 1952, he had a nonspeaking bit part as a pressman in the movie Deadline – U.S.A., starring Humphrey Bogart.[20]

Proud of these accomplishments, Dean referred to the Actors Studio in a 1952 letter to his family as "the greatest school of the theater. It houses great people like Marlon Brando, Julie Harris, Arthur Kennedy, [[Mildred Dunnock, Eli Wallach ... Very few get into it ... It is the best thing that can happen to an actor. I am one of the youngest to belong."[19] There, he was classmates and close friends with Carroll Baker, alongside whom he would eventually star in Giant (1956).

Dean's career picked up and he performed in further episodes of such early 1950s television shows as Kraft Television Theatre, Robert Montgomery Presents, The United States Steel Hour, Danger, and General Electric Theater. One early role, for the CBS series Omnibus in the episode "Glory in the Flower", saw Dean portraying the type of disaffected youth he would later portray in Rebel Without a Cause (1955). Positive reviews for Dean's 1954 theatrical role as Bachir, a pandering homosexual North African houseboy, in an adaptation of André Gide's book The Immoralist (1902), led to calls from Hollywood.[21] During the production of The Immoralist, Dean had an affair with actress Geraldine Page. Angelica Page said of their relationship:

According to my mother, their affair went on for three-and-a-half months. In many ways my mother never really got over Jimmy. It was not unusual for me to go to her dressing room through the years, obviously many years after Dean was gone, and find pictures of him taped up on her mirror. My mother never forgot about Jimmy — never. I believe they were artistic soul mates."[22]

Page remained friends with Dean until his death and kept a number of personal mementos from the play—including several drawings by him.[23]

East of Eden

In 1953, director Elia Kazan was looking for a substantive actor to play the emotionally complex role of Cal Trask, for screenwriter Paul Osborn's adaptation of John Steinbeck's 1952 novel East of Eden. This book deals with the story of the Trask and Hamilton families over the course of three generations, focusing especially on the lives of the latter two generations in Salinas Valley, California, from the mid-nineteenth century through the 1910s.

In contrast to the book, the film script focused on the last portion of the story, predominantly with the character of Cal. Though he initially seems more aloof and emotionally troubled than his twin brother Aron, Cal is soon seen to be more worldly, business savvy, and even sagacious than their pious and constantly disapproving father (played by Raymond Massey) who seeks to invent a vegetable refrigeration process. Cal is bothered by the mystery of their supposedly dead mother, and discovers she is still alive and a brothel-keeping 'madam'; the part was played by actress Jo Van Fleet.[24]

Before casting Cal, Elia Kazan said that he wanted "a Brando" for the role and Osborn suggested Dean, a relatively unknown young actor. Dean met with Steinbeck, who did not like the moody, complex young man personally, but thought him to be perfect for the part. Dean was cast in the role and on April 8, 1954, left New York City and headed for Los Angeles to begin shooting.[5][3]

Much of Dean's performance in the film was unscripted,[25] including his dance in the bean field and his fetal-like posturing while riding on top of a train boxcar (after searching out his mother in nearby Monterey). The best-known improvised sequence of the film occurs when Cal's father rejects his gift of $5,000, money Cal earned by speculating in beans before the US became involved in World War I. Instead of running away from his father as the script called for, Dean instinctively turned to Massey and in a gesture of extreme emotion, lunged forward and grabbed him in a full embrace, crying. Kazan kept this and Massey's shocked reaction in the film.

Dean's performance in the film foreshadowed his role as Jim Stark in Rebel Without A Cause. Both characters are angst-ridden protagonists and misunderstood outcasts, desperately craving approval from their fathers.[12]

In recognition of his performance in East of Eden, Dean was nominated posthumously for the 1956 Academy Awards as Best Actor in a Leading Role of 1955, the first official posthumous acting nomination in Academy Awards history.[3] (Jeanne Eagels was nominated for Best Actress in 1929, when the rules for selection of the winner were different.) East of Eden was the only film starring Dean released in his lifetime.[18]

Rebel Without a Cause, Giant and planned roles

Dean quickly followed up his role in Eden with a starring role as Jim Stark in Rebel Without a Cause (1955), a film that would prove to be hugely popular among teenagers. The film has been cited as an accurate representation of teenage angst.[14]

Following East of Eden and Rebel Without a Cause, Dean wanted to avoid being typecast as a rebellious teenager like Cal Trask or Jim Stark, and hence took on the role of Jett Rink, a Texan ranch hand who strikes oil and becomes wealthy, in Giant, a posthumously released 1956 film. The movie portrays a number of decades in the lives of Bick Benedict, a Texas rancher, played by Rock Hudson; his wife, Leslie, played by Elizabeth Taylor; and Rink. To portray an older version of his character in the film's later scenes, Dean dyed his hair gray and shaved some of it off to give himself a receding hairline.

Giant would prove to be Dean's last film. At the end of the film, Dean was supposed to make a drunken speech at a banquet; this is nicknamed the 'Last Supper' because it was the last scene before his sudden death. Due to his desire to make the scene more realistic by actually being inebriated for the take, Dean mumbled so much that director George Stevens decided the scene had to be overdubbed by Nick Adams, who had a small role in the film, because Dean had died before the film was edited.

Dean received his second posthumous Best Actor Academy Award nomination for his role in Giant at the 29th Academy Awards in 1957 for films released in 1956. Dean was the first to receive a posthumous Academy Award nomination for acting and is the only actor to have received two such posthumous nominations.[26]

Having finished Giant, Dean was set to star as Rocky Graziano in a drama film, Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956), and, according to Nicholas Ray himself, he was going to do a story called Heroic Love with the director.[27] Dean's death terminated any involvement in the projects but Somebody Up There Likes Me still went on to earn both commercial and critical success, winning two Oscars and grossing $3,360,000, with Paul Newman playing the role of Graziano.

Death

Auto racing hobby

In 1954, Dean became interested in developing a career in motorsport. He purchased various vehicles after filming for East of Eden had concluded, including a Triumph Tiger T110 and a Porsche 356.[3] Just before filming began on Rebel Without a Cause, he competed in his first professional event at the Palm Springs Road Races, which was held in Palm Springs, California on March 26–27, 1955. Dean achieved first place in the novice class, and second place at the main event. His racing continued in Bakersfield a month later, where he finished first in his class and third overall.[28] Dean hoped to compete in the Indianapolis 500, but his busy schedule made it impossible.[3]

Dean's final race occurred in Santa Barbara on Memorial Day, May 30, 1955. He was unable to finish the competition due to a blown piston. His brief career was put on hold when Warner Brothers barred him from all racing during the production of Giant.[28] Dean had finished shooting his scenes and the movie was in post-production when he decided to race again.

Accident and aftermath

Longing to return to the "liberating prospects" of motor racing, Dean traded in his Speedster for a new, more powerful and faster 1955 Porsche 550 Spyder and entered the Salinas Road Race event scheduled for October 1–2, 1955.[28] Accompanying the actor on his way to the track on September 30 was stunt coordinator Bill Hickman, Collier's photographer Sanford Roth, and Rolf Wütherich, the German mechanic from the Porsche factory who maintained Dean's Spyder car, "Little Bastard."[3] Wütherich, who had encouraged Dean to drive the car from Los Angeles to Salinas to break it in, accompanied Dean in the Porsche. At 3:30 p.m., Dean was ticketed for speeding, as was Hickman, who was following behind in another car.

As the group was driving westbound on U.S. Route 466 (currently SR 46) near Cholame, California, at approximately 5:45 p.m., a 1950 Ford Tudor, driven by 23-year-old California Polytechnic State University student Donald Turnupseed, was traveling east.[29] Turnupseed made a left turn onto Highway 41 headed north, toward Fresno[15] ahead of the oncoming Porsche.[3][30]

Dean, unable to stop in time, slammed into the passenger side of the Ford, resulting in Dean's car bouncing across the pavement onto the side of the highway. Dean's passenger, Wütherich, was thrown from the Porsche, while Dean was trapped in the car and sustained numerous fatal injuries, including a broken neck.[3] Turnupseed exited his damaged vehicle with minor injuries.

The accident was witnessed by a number of passersby who stopped to help. Dean's biographer George Perry wrote that a woman with nursing experience attended to Dean and detected a weak pulse, but he also contrarily wrote that "death appeared to have been instantaneous."[3] Dean was pronounced dead on arrival shortly after he arrived by ambulance at the Paso Robles War Memorial Hospital at 6:20 p.m.[28]

Though initially slow to reach newspapers in the Eastern United States, details of Dean's death rapidly spread via radio and television. By October 2, his death had received significant coverage from domestic and foreign media outlets.[3] Dean's funeral was held on October 8, 1955, at the Fairmount Friends Church in Fairmount, Indiana. The coffin remained closed to conceal his severe injuries. An estimated 600 mourners were in attendance, while another 2,400 fans gathered outside of the building during the procession.[3] He is buried at Park Cemetery in Fairmount, second road to the right from the main entrance, and up the hill on the right, facing the drive.[31]

An inquest into Dean's death occurred three days later at the council chambers in San Luis Obispo, where the sheriff-coroner's jury delivered the verdict that Dean was entirely at fault due to speeding, and that Turnupseed was innocent of any criminal act. This verdict has remained controversial:

All conjecture was improper. The facts were that Jimmy had been in his proper lane, there was no evidence that his speed was a factor in the crash, and the other driver had crossed over into Jimmy's right of way. The jury's verdict flew in the face of the accepted logic of highway accidents, which holds that when a left turn is executed in the face of oncoming traffic it is the turning driver who is responsible should a collision occur.[32]

A "James Dean Monument" was placed in Cholame next to Highway 46, and stands to this day.[33]

Personal life

Dean had a number of romantic relationships with actresses. Screenwriter William Bast was one of Dean's closest friends, a fact acknowledged by Dean's family.[3] According to Bast, he was Dean's roommate at UCLA and later in New York, and knew Dean throughout the last five years of his life, during his acting career.[19] While at UCLA, Dean dated Beverly Wills, an actress with CBS, and Jeanette Lewis, a classmate. Bast and Dean often double-dated with them. Wills began dating Dean alone, later telling Bast, "Bill, there's something we have to tell you. It's Jimmy and me. I mean, we're in love."[2] They broke up after Dean "exploded" when another man asked her to dance while they were at a function.[2]

Actress Liz Sheridan detailed her relationship with Dean in New York in 1952, saying in her memoir published in 2000, that it was "just kind of magical. ... It was the first love for both of us."[34]

While living in New York, Dean was introduced to actress Barbara Glenn by their mutual friend Martin Landau. They dated for two years, often breaking up and getting back together.[2]

After Dean signed his contract with Warner Brothers, the studio's public relations department began generating stories about Dean's liaisons with a variety of young actresses who were mostly drawn from the clientele of Dean's Hollywood agent, Dick Clayton. Studio press releases also grouped Dean together with two other actors, Rock Hudson and Tab Hunter, identifying each of the men as an 'eligible bachelor' who had not yet found the time to commit to a single woman: "They say their film rehearsals are in conflict with their marriage rehearsals."[4]

Dean's best-remembered relationship was with young Italian actress Pier Angeli. He met Angeli while she was shooting The Silver Chalice (1954) on an adjoining Warner lot, and with whom he exchanged items of jewelry as love tokens. Dean was quoted saying about Angeli, "Everything about Pier is beautiful, especially her soul. She doesn't have to be all gussied up. She doesn't have to do or say anything. She's just wonderful as she is. She has a rare insight into life."[5]

Those who believed Dean and Angeli were deeply in love claimed that a number of forces led them apart. Angeli's mother disapproved of Dean's casual dress and what were, for her at least, unacceptable behavior traits: his T-shirt attire, late dates, fast cars, drinking, and the fact that he was not a Catholic. Her mother said that such behavior was not acceptable in Italy. In addition, Warner Bros., where he worked, tried to talk him out of marrying and he himself told Angeli that he did not want to get married.[2] Richard Davalos, Dean's East of Eden co-star, claimed that Dean in fact wanted to marry Angeli and was willing to allow their children to be brought up Catholic.[35] An Order for the Solemnization of Marriage pamphlet with the name "Pier" lightly penciled in every place the bride's name is left blank was found amongst Dean's personal effects after his death.[11]

Some commentators, such as William Bast and Paul Alexander, believe the relationship was a mere publicity stunt.[9][19] In his autobiography, Elia Kazan, the director of East of Eden, dismissed the notion that Dean could possibly have had any success with women, although he remembered hearing Dean and Angeli loudly making love in Dean's dressing room.[35]

After finishing his role for East of Eden, Dean took a brief trip to New York in October 1954.[2] While he was away, Angeli unexpectedly announced her engagement to Italian-American singer Vic Damone. The press was shocked and Dean expressed his irritation.[19] Angeli married Damone the following month. Gossip columnists reported that Dean watched the wedding from across the road on his motorcycle, even gunning the engine during the ceremony, although Dean later denied doing anything so "dumb."[2] Joe Hyams claims that he visited Dean just as Angeli, then married to Damone, was leaving his home. Dean was crying and allegedly told Hyams she was pregnant, with Hyams concluding that Dean believed the child might be his.[11]

Angeli, who divorced Damone and then her second husband, the Italian film composer Armando Trovajoli, was said by friends in the last years of her life to claim that Dean was the love of her life. She talked only once about the relationship in an interview, giving vivid descriptions of romantic meetings at the beach:

We used to go together to the California coast and stay there secretly in a cottage on a beach far away from prying eyes. We'd spend much of our time on the beach, sitting there or fooling around, just like college kids. We would talk about ourselves and our problems, about the movies and acting, about life and life after death. We had a complete understanding of each other. We were like Romeo and Juliet, together and inseparable. Sometimes on the beach we loved each other so much we just wanted to walk together into the sea holding hands because we knew then that we would always be together.[2]

Dean biographer John Howlett said these read like wishful fantasies,[36] as Bast claims them to be.[19]

Sexuality

Dean is often considered a sexual icon because of his perceived experimental take on life, which included his ambivalent sexuality. When questioned about his sexual orientation, Dean is reported to have said, "No, I am not a homosexual. But I'm also not going to go through life with one hand tied behind my back."[21]

Journalist Joe Hyams suggests that any gay activity Dean might have been involved in appears to have been strictly "for trade," as a means of advancing his career. Some point to Dean's involvement with Rogers Brackett as evidence of this. For example, William Bast referred to Dean as Brackett's "kept boy" and once found a grotesque depiction of a lizard with the head of Brackett in a sketchbook belonging to Dean.[19]

However, the "trade only" notion is contradicted by several Dean biographers.[37][5] Bast, Dean's friend since college and his first biographer,[38] would not confirm whether he and Dean had a sexual relationship until 2006. In his book Surviving James Dean, Bast was more open about the nature of his relationship with Dean, writing that they had been lovers one night while staying at a hotel in Borrego Springs.[19] In his book, Bast also described the difficult circumstances of their involvement.

Aside from Bast's account of his own relationship with Dean, Dean's fellow motorcyclist and "Night Watch" member, John Gilmore, claimed that he and Dean "experimented" with gay sex on multiple occasions in New York, describing their sexual encounters as "Bad boys playing bad boys while opening up the bisexual sides of ourselves."[39]

On the subject of Dean's sexuality, Rebel director Nicholas Ray is on record saying:

James Dean was not straight, he was not gay, he was bisexual. That seems to confuse people, or they just ignore the facts. Some—most—will say he was heterosexual, and there's some proof for that, apart from the usual dating of actresses his age. Others will say no, he was gay, and there's some proof for that too, keeping in mind that it's always tougher to get that kind of proof. But Jimmy himself said more than once that he swung both ways, so why all the mystery or confusion?"[40]

Legacy and iconic status

James Dean died when he was only 24 years old, yet he remains an icon of troubled youth, adolescent torment personified. American teenagers of the mid-1950s, when Dean's major films were first released, identified with Dean and the roles he played, especially that of Jim Stark in Rebel Without a Cause. The film depicts the dilemma of a typical teenager of the time, who feels that no one, not even his peers, can understand him.

In a way he fulfilled his own words: "If a man can bridge the gap between life and death, I mean, if he can live on after he's died, then maybe he was a great man."[41] Humphrey Bogart commented after Dean's death about his public image and legacy: "Dean died at just the right time. He left behind a legend. If he had lived, he'd never have been able to live up to his publicity."[42]

Joe Hyams says that Dean was "one of the rare stars, like Rock Hudson and Montgomery Clift, whom both men and women find sexy."[11] Dean's iconic appeal has been attributed to the public's need for someone to stand up for the disenfranchised young of the era,[3] and to the air of androgyny that he projected onscreen.[43]

Dean's legacy remains potent, as evidenced by the number of biographies and movies about his life that have continued to be produced over the decades since his death. His estate continued to earn millions per year, according to Forbes magazine.[44]

Cinema and television

Dean has been a touchstone of many television shows, films, books and plays. The film September 30, 1955 (1977) depicts the ways various characters in a small Southern town in the US react to Dean's death.[45] The play Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean, written by Ed Graczyk, depicts a reunion of Dean fans on the twentieth anniversary of his death. It was staged by the director Robert Altman in 1982, but was poorly received and closed after only 52 performances. While the play was still running on Broadway, Altman shot a film adaptation that was released by Cinecom Pictures in November 1982.[46]

Dean influenced many successful actors. Martin Sheen has been vocal throughout his career about being influenced by James Dean. Speaking of the impact Dean had on him, Sheen stated:

All of his movies had a profound effect on my life, in my work and all of my generation. He transcended cinema acting. It was no longer acting, it was human behavior.[47]

Johnny Depp credited Dean as the catalyst that made him want to become an actor,[48] as did Nicolas Cage:

I started acting because I wanted to be James Dean. I saw him in Rebel Without a Cause, East of Eden. Nothing affected me – no rock song, no classical music – the way Dean affected me in Eden. It blew my mind. I was like, 'That's what I want to do.'[49]

Leonardo DiCaprio also cited Dean as one of his favorite and most influential actors:

I remember being incredibly moved by Jimmy Dean, in East of Eden. There was something so raw and powerful about that performance. His vulnerability…his confusion about his entire history, his identity, his desperation to be loved. That performance just broke my heart.[50]

Youth culture and music

While the magnetism and charisma manifested by Dean onscreen appealed to people of all ages and sexuality,[6] his persona of youthful rebellion provided a template for succeeding generations of youth to model themselves on.[14][51] In his book, The Origins of Cool in Postwar America, Joel Dinerstein describes how Dean and Marlon Brando eroticized the rebel archetype in film, and how Elvis Presley, following their lead, did the same in music.[52]

Numerous commentators have asserted that Dean had a singular influence on the development of rock and roll music. The persona Dean projected in his movies, especially Rebel Without a Cause, influenced Presley and many other musicians who followed, including the American rockers Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent. In this way, "As rock music became the defining expression of youth in the 1960s, the influence of Rebel was conveyed to a new generation."[40] According to David R. Shumway, a researcher in American culture and cultural theory at Carnegie Mellon University, Dean was the first iconic figure of youthful rebellion and "a harbinger of youth-identity politics."[53] Dean himself listened to a wide range of music, including the modern classical music of Stravinsky[54] and Bartók,[32] as well as to contemporary singers such as Frank Sinatra.[54]

In their book, Live Fast, Die Young: The Wild Ride of Making Rebel Without a Cause, Lawrence Frascella and Al Weisel wrote:

Ironically, though Rebel had no rock music on its soundtrack, the film's sensibility—and especially the defiant attitude and effortless cool of James Dean—would have a great impact on rock. The music media would often see Dean and rock as inextricably linked [...] The industry trade magazine Music Connection even went so far as to call Dean 'the first rock star.'[40]

Rock musicians as diverse as Buddy Holly,[41] Bob Dylan, and David Bowie[55] regarded Dean as a formative influence. Dean's acting in Rebel Without a Cause provided a "performance model for Presley, Buddy Holly, and Bob Dylan, all of whom borrowed elements of Dean's performance in their own carefully constructed star personas."[56] For example, a young Bob Dylan, still in his folk music period, consciously evoked Dean visually on the cover of his album, The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan (1963),[2] and later on Highway 61 Revisited (1965),[57] cultivating an image that his biographer Bob Spitz called "James Dean with a guitar."[58]

Dean and Presley have often been represented in academic literature and in journalism as embodying the frustration felt by young white Americans with the values of their parents: "The sense of alienation from society and distrust of authority that was inherent in the leather jacket of James Dean or the blue jeans of Elvis Presley was incorporated into the modern sensibility of youth."[59] and depicted as avatars of the youthful unrest endemic to rock and roll style and attitude.

Stage credits

- Broadway

- See the Jaguar (1952)

- The Immoralist (1954) – based on the book by André Gide

- Off-Broadway

- The Metamorphosis (1952) – based on the short story by Franz Kafka

- The Scarecrow (1954)

- Women of Trachis (1954) – translation by Ezra Pound

Filmography

Film

| Year | Title | Role | Director | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | Fixed Bayonets! | Doggie | Samuel Fuller | Uncredited |

| 1952 | Sailor Beware | Boxing Trainer | Hal Walker | Uncredited |

| 1952 | Deadline – U.S.A. | Copyboy | Richard Brooks | Uncredited |

| 1952 | Has Anybody Seen My Gal? | Youth at Soda Fountain | Douglas Sirk | Uncredited |

| 1953 | Trouble Along the Way | Football Spectator | Michael Curtiz | Uncredited |

| 1955 | East of Eden | Cal Trask | Elia Kazan | Golden Globe Special Achievement Award for Best Dramatic Actor Jussi Award for Best Foreign Actor Nominated – Academy Award for Best Actor Nominated – BAFTA Award for Best Foreign Actor |

| 1955 | Rebel Without a Cause | Jim Stark | Nicholas Ray | Nominated – BAFTA Award for Best Foreign Actor |

| 1956 | Giant | Jett Rink | George Stevens | Nominated – Academy Award for Best Actor |

Television

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | Family Theater | John the Apostle | Episode: "Hill Number One: A Story of Faith and Inspiration" |

| 1951 | The Bigelow Theatre | Hank | Episode: "T.K.O." |

| 1951 | The Stu Erwin Show | Randy | Episode: "Jackie Knows All" |

| 1952 | CBS Television Workshop | G.I. | Episode: "Into the Valley" |

| 1952 | Hallmark Hall of Fame | Bradford | Episode: "Forgotten Children" |

| 1952 | The Web | Himself | Episode: "Sleeping Dogs" |

| 1952–1953 | Kraft Television Theatre | Various Characters | Episodes: "Prologue to Glory", "Keep Our Honor Bright" and "A Long Time Till Dawn" |

| 1952–1955 | Lux Video Theatre | Various Characters | Episodes: "The Foggy, Foggy Dew" and "The Life of Emile Zola" |

| 1953 | The Kate Smith Hour | The Messenger | Episode: "The Hound of Heaven" |

| 1953 | You Are There | Robert Ford | Episode: "The Capture of Jesse James" |

| 1953 | Treasury Men in Action | Various Characters | Episodes: "The Case of the Watchful Dog" and "The Case of the Sawed-Off Shotgun" |

| 1953 | Tales of Tomorrow | Ralph | Episode: "The Evil Within" |

| 1953 | Westinghouse Studio One | Various Characters | Episodes: "Ten Thousand Horses Singing", "Abraham Lincoln" and "Sentence of Death" |

| 1953 | The Big Story | Rex Newman | Episode: "Rex Newman, Reporter for the Globe and News" |

| 1953 | Omnibus | Bronco Evans | Episode: "Glory in the Flower" |

| 1953 | Campbell Summer Soundstage | Various Characters | Episodes: "Something for an Empty Briefcase" and "Life Sentence" |

| 1953 | Armstrong Circle Theatre | Joey Frasier | Episode: "The Bells of Cockaigne" |

| 1953 | Robert Montgomery Presents | Paul Zalinka | Episode: "Harvest" |

| 1953–1954 | Danger | Various Characters | Episodes: "No Room", "Death Is My Neighbor", "The Little Woman" and "Padlocks" |

| 1954 | The Philco Television Playhouse | Rob | Episode: "Run Like a Thief" |

| 1954 | General Electric Theater | Various Characters | Episodes: "I'm a Fool" and "The Dark, Dark Hours" |

| 1955 | The United States Steel Hour | Fernand Lagarde | Episode: "The Thief" |

| 1955 | Schlitz Playhouse | Jeffrey Latham | Episode: "The Unlighted Road" |

Biographical films about Dean

- James Dean also known as James Dean: Portrait of a Friend (1976) with Stephen McHattie as James Dean

- James Dean: The First American Teenager (1976), a television biography that includes interviews with Sal Mineo, Natalie Wood and Nicholas Ray.

- Forever James Dean (1988), Warner Home Video (1995)

- James Dean: The Final Day features interviews with William Bast, Liz Sheridan and Maila Nurmi. Dean's bisexuality is openly discussed. Episode of Naked Hollywood television miniseries produced by The Oxford Film Company in association the BBC, aired in the US on the A&E Network, 1991.

- James Dean: Race with Destiny (1997) directed by Mardi Rustam, starring Casper Van Dien as James Dean.

- James Dean (fictionalized TV biographical film) (2001) with James Franco as James Dean

- James Dean – Outside the Lines (2002), episode of Biography, US television documentary includes interviews with Rod Steiger, William Bast, and Martin Landau (2002).

- Living Famously: James Dean, Australian television biography includes interviews with Martin Landau, Betsy Palmer, William Bast, and Bob Hinkle (2003, 2006).

- James Dean – Kleiner Prinz, Little Bastard aka James Dean – Little Prince, Little Bastard, German television biography, includes interviews with William Bast, Marcus Winslow Jr, Robert Heller (2005)

- Sense Memories (PBS American Masters television biography) (2005)

- James Dean – Mit Vollgas durchs Leben, Austrian television biography includes interviews with Rolf Weutherich and William Bast (2005).

- Two Friendly Ghosts (2012)

- Joshua Tree, 1951: A Portrait of James Dean (2012), with James Preston as James Dean.

Notes

- ↑ Chris Epting, The Birthplace Book: A Guide to Birth Sites of Famous People, Places, & Things (Stackpole Books, 2009, ISBN 978-0811735339).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 David Dalton, James Dean-The Mutant King: A Biography (Chicago Review Press, 2001, ISBN 978-1556523984).

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 George Perry, James Dean (DK Publishing, 2005, ISBN 978-0756609344).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Michael DeAngelis, Gay Fandom and Crossover Stardom: James Dean, Mel Gibson, and Keanu Reeves (Duke University Press Books, 2001, ISBN 978-0822327288).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Val Holley, James Dean: The Biography (St. Martin's Griffin, 1995, ISBN 978-0312132491).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Robert Tanitch, The Unknown James Dean (B T Batsford Ltd, 1999, ISBN 978-0713480344).

- ↑ Marie Clayton, James Dean - A Life In Pictures (Barnes & Noble, 2004, ISBN 978-0760756140).

- ↑ Billy J, Harbin, Kimberley Bell Marra, and Robert A. Schanke (eds.), The Gay and Lesbian Theatrical Legacy: A Biographical Dictionary of Major Figures in American Stage History in the Pre-Stonewall Era (University of Michigan Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0472068586).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Paul Alexander, Boulevard of Broken Dreams: The Life, Times, and Legend of James Dean (Viking, 1994, ISBN 0670849510).

- ↑ Kevin Sessums, Elizabeth Taylor Interview About Her AIDS Advocacy, Plus Stars Remember The Daily Beast, July 13, 2017. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Joe Hyams, James Dean: Little Boy Lost (Grand Central Publishing, 1992, ISBN 0446516430).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Karen Clemens Warrick, James Dean: Dream as If You'll Live Forever (Enslow Pub Inc, 2006, ISBN 978-0766025370).

- ↑ Joyce Chandler, James Dean: A Rebel with a Cause: A Fans Tribute (AuthorHouse, 2007, ISBN 978-1434318206).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Claudia Springer, James Dean Transfigured: The Many Faces of Rebel Iconography (University of Texas Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0292714434).

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Keith Elliot Greenberg, Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die - James Dean's Final Hours (Applause, 2015, ISBN 978-1480360303).

- ↑ David Bleiler (ed.), TLA Film and Video Guide 2000-2001: The Discerning Film Lover's Guide (Griffin, 1999, ISBN 978-0312243302).

- ↑ Tony Curtis, American Prince: A Memoir (Three Rivers Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0312243302).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 R. Barton Palmer (ed.), Larger Than Life: Movie Stars of the 1950s (Rutgers University Press, 2010, ISBN 0813547660).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 19.6 19.7 William Bast, Surviving James Dean (Barricade Books, 2006, ISBN 978-1569802984).

- ↑ Leonard Maltin, Turner Classic Movies Presents Leonard Maltin's Classic Movie Guide: From the Silent Era Through 1965 (Plume, 2015, ISBN 978-0147516824).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Randall Riese, The Unabridged James Dean: His Life & Legacy from A-Z (Random House Value Publishing, 1994, ISBN 978-0517100813).

- ↑ Paul Alexander, The Woman Who Made James Dean a Star HuffPost, Octobet 2, 2015. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ↑ Gary Dowell, Isaiah Evans, Kim Jones, and James L. Halperin, Heritage Music and Entertainment Dallas Signature Auction Catalog #634 (Heritage Auctions, Inc., 2006, ISBN 978-1599670812).

- ↑ Michael J. Meyer and Henry Veggian (eds.), East of Eden: New and Recent Essays (Rodopi, 2013, ISBN 978-9042037120).

- ↑ Bruce Levene (ed.), James Dean in Mendocino: The Filming of East of Eden (Pacific Transcriptions, 2001, ISBN 978-0933391130).

- ↑ David S. Kidder and Noah D. Oppenheim, The Intellectual Devotional Modern Culture: Revive Your Mind, Complete Your Education, and Converse Confidently with the Culturati (Rodale Books, 2008, ISBN 978-1594867453).

- ↑ Nicholas Ray, Dean, the Actor as a Young Man: 'Rebel Without a Cause' Director Nicholas Ray Remembers the 'Impossible' Artist The Daily Beast, February 10, 2016.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Lee Raskin, James Dean: At Speed (David Bull Publishing, 2005, ISBN 978-1893618497).

- ↑ James Dean dies in car accident This Day in History, A&E Television Networks, November 13, 2009. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ↑ John Houghton, Remembering James Dean's death on Highway 46 Your Central Valley, September 30, 2019. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ↑ Scott Wilson, Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons (McFarland, 2016. ISBN 978-0786479924).

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Warren N. Beath, The Death of James Dean (Grove Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0802131430).

- ↑ Ken Figlioli, The James Dean Memorial in Cholame Discover Central California. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ↑ Liz Sheridan, Dizzy & Jimmy: My Life with James Dean: A Love Story (Harper, 2000, ISBN 978-0060393830).

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Jane Allen, Pier Angeli: A Fragile Life (McFarland & Company, 2002, ISBN 978-0786413928).

- ↑ John Howlett, James Dean: A Biography (Plexus Publishing, 1994. ISBN 978-0859650120).

- ↑ Donald Spoto, Rebel: The Life and Legend of James Dean (HarperCollins, 1996, ISBN 978-0060176563).

- ↑ William Bast, James Dean: a Biography (New York: Ballantine Books, 1956).

- ↑ John Gilmore, Live Fast, Die Young: Remembering the Short Life of James Dean (Thunder's Mouth Press, 1997, ISBN 978-1560251460).

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Lawrence Frascella and Al Weisel, Live Fast, Die Young: The Wild Ride of Making Rebel Without a Cause (Touchstone, 2005, ISBN 978-0743260824).

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 John Howlett, James Dean: Rebel Life (Plexus Publishing, 2016, ISBN 978-0859655347).

- ↑ Ron Martinetti, Rebel For All Seasons American Legends. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ↑ David Burner, Making Peace with the 60s (Princeton University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0691026602).

- ↑ Reaping Millions After Death Forbes, October 26, 2004. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ↑ James Monaco, How to Read a Film: The Art, Technology, Language, History, and Theory of Film and Media (Oxford University Press, 1981, ISBN 978-0195028027).

- ↑ Robert Niemi, The Cinema of Robert Altman: Hollywood Maverick (Wallflower Press, 2016, ISBN 978-0231850865).

- ↑ Friends of James Dean remember iconic star Today, February 8, 2005. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ↑ Hooked on Dean, says Johnny Depp BBC, September 26, 2005. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ↑ Jenn Selby, Nicolas Cage on the rise of the 'celebutard': 'It sucks to be famous right now' The Independent, March 11, 2014. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ↑ Mike Fleming Jr, Leonardo DiCaprio On The Hard-Knock Film Education That Led To 'The Revenant': Q&A Deadline, February 10, 2016. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ↑ Wayne Robins, A Brief History of Rock, Off the Record (Routledge, 2007, ISBN 0415974720).

- ↑ Joel Dinerstein, The Origins of Cool in Postwar America (University of Chicago Press, 2017, ISBN 0226152650).

- ↑ David A. Shumway, "Rock Stars as Icons" in Andy Bennett and Steve Waksman (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Popular Music (SAGE Publications Ltd, 2015, ISBN 978-1446210857).

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Peter Winkler (ed.), The Real James Dean: Intimate Memories from Those Who Knew Him Best (Chicago Review Press, 2016, ISBN 978-1613734728).

- ↑ Marc Spitz, Bowie: A Biography (Crown, 2010, ISBN 978-0307716996).

- ↑ Steven Rybin and Will Scheibel (eds.), Lonely Places, Dangerous Ground: Nicholas Ray in American Cinema (SUNY Press, 2014, ISBN 978-1438449814).

- ↑ David Dalton, Who Is That Man? In Search of the Real Bob Dylan (Hyperion, 2012, ISBN 978-1401323394).

- ↑ Bob Spitz, Dylan: A Biography (W. W. Norton & Company, 1991, ISBN 978-0393307696).

- ↑ Doug Owram, Born at the Right Time: A History of the Baby-boom Generation (University of Toronto Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0802080868).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alexander, Paul. Boulevard of Broken Dreams: The Life, Times, and Legend of James Dean. Viking, 1994. ISBN 0670849510

- Allen, Jane. Pier Angeli: A Fragile Life. McFarland & Company, 2002. ISBN 978-0786413928

- Bast, William. James Dean: A Biography. Ballantine Books, 1956. ASIN B001FBFIX2

- Bast, William. Surviving James Dean. Barricade Books, 2006. ISBN 978-1569802984

- Beath, Warren N. The Death of James Dean. Grove Press, 1994 ISBN 978-0802131430

- Bennett, Andy, and Steve Waksman (eds.). The SAGE Handbook of Popular Music. SAGE Publications Ltd, 2015. ISBN 978-1446210857

- Bleiler, David (ed.). TLA Film and Video Guide 2000-2001: The Discerning Film Lover's Guide. Griffin, 1999. ISBN 978-0312243302

- Burner, David. Making Peace with the 60s. Princeton University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0691026602

- Chandler, Joyce. James Dean: A Rebel with a Cause: A Fans Tribute. AuthorHouse, 2007. ISBN 978-1434318206

- Clayton, Marie. James Dean - A Life In Pictures. Barnes & Noble, 2004. ISBN 978-0760756140

- Curtis, Tony. American Prince: A Memoir. Three Rivers Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0312243302

- Dalton, David. James Dean-The Mutant King: A Biography. Chicago Review Press, 2001. ISBN 978-1556523984

- Dalton, David. Who Is That Man? In Search of the Real Bob Dylan. Hyperion, 2012. ISBN 978-1401323394

- DeAngelis, Michael. Gay Fandom and Crossover Stardom: James Dean, Mel Gibson, and Keanu Reeves. Duke University Press Books, 2001. ISBN 978-0822327288

- Dinerstein, Joel. The Origins of Cool in Postwar America. University of Chicago Press, 2017. ISBN 0226152650

- Dowell, Gary, Isaiah Evans, Kim Jones, and James L. Halperin. Heritage Music and Entertainment Dallas Signature Auction Catalog #634. Heritage Auctions, Inc., 2006. ISBN 978-1599670812

- Epting, Chris. The Birthplace Book: A Guide to Birth Sites of Famous People, Places, & Things. Stackpole Books, 2009. ISBN 978-0811735339

- Frascella, Lawrence and Al Weisel. Live Fast, Die Young: The Wild Ride of Making Rebel Without a Cause. Touchstone, 2005. ISBN 978-0743260824

- Gilmore, John. Live Fast, Die Young: Remembering the Short Life of James Dean. Thunder's Mouth Press, 1997. ISBN 978-1560251460

- Greenberg, Keith Elliot. Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die - James Dean's Final Hours. Applause, 2015. ISBN 978-1480360303

- Harbin, Billy J., Kimberley Bell Marra, and Robert A. Schanke (eds.). The Gay and Lesbian Theatrical Legacy: A Biographical Dictionary of Major Figures in American Stage History in the Pre-Stonewall Era. University of Michigan Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0472068586

- Holley, Val. James Dean: The Biography. St. Martin's Griffin, 1995. ISBN 978-0312132491

- Howlett, John. James Dean: A Biography. Plexus Publishing, 1994. ISBN 978-0859650120

- Howlett, John. James Dean: Rebel Life. Plexus Publishing, 2016. ISBN 978-0859655347

- Hyams, Joe. James Dean: Little Boy Lost. Grand Central Publishing, 1992. ISBN 0446516430

- Kidder, David S., and Noah D. Oppenheim. The Intellectual Devotional Modern Culture: Revive Your Mind, Complete Your Education, and Converse Confidently with the Culturati. Rodale Books, 2008. ISBN 978-1594867453

- Levene, Bruce (ed.). James Dean in Mendocino: The Filming of East of Eden. Pacific Transcriptions, 2001. ISBN 978-0933391130

- Maltin, Leonard. Turner Classic Movies Presents Leonard Maltin's Classic Movie Guide: From the Silent Era Through 1965. Plume, 2015. ISBN 978-0147516824

- Meyer, Michael J., and Henry Veggian (eds.). East of Eden: New and Recent Essays. Rodopi, 2013. ISBN 978-9042037120

- Monaco, James. How to Read a Film: The Art, Technology, Language, History, and Theory of Film and Media. Oxford University Press, 1981. ISBN 978-0195028027

- Niemi, Robert. The Cinema of Robert Altman: Hollywood Maverick. Wallflower Press, 2016. ISBN 978-0231850865

- Owram, Doug. Born at the Right Time: A History of the Baby-boom Generation. University of Toronto Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0802080868

- Palmer, R. Barton (ed.). Larger Than Life: Movie Stars of the 1950s . Rutgers University Press, 2010. ISBN 0813547660

- Perry, George. James Dean. DK Publishing, 2005. ISBN 978-0756609344

- Raskin, Lee. James Dean: At Speed. David Bull Publishing, 2005. ISBN 978-1893618497

- Riese, Randall. The Unabridged James Dean: His Life & Legacy from A-Z. Random House Value Publishing, 1994. ISBN 978-0517100813

- Robins, Wayne. A Brief History of Rock, Off the Record. Routledge, 2007. ISBN 0415974720

- Rybin, Steven, and Will Scheibel (eds.). Lonely Places, Dangerous Ground: Nicholas Ray in American Cinema. SUNY Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1438449814

- Spitz, Bob. Dylan: A Biography. W. W. Norton & Company, 1991. ISBN 978-0393307696

- Spitz, Marc. Bowie: A Biography. Crown, 2010. ISBN 978-0307716996

- Spoto, Donald: Rebel: The Life and Legend of James Dean. HarperCollins, 1996. ISBN 978-0060176563

- Springer, Claudia. James Dean Transfigured: The Many Faces of Rebel Iconography. University of Texas Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0292714434

- Tanitch, Robert. The Unknown James Dean. B T Batsford Ltd, 1999. ISBN 978-0713480344

- Warrick, Karen Clemens. James Dean: Dream as If You'll Live Forever. Enslow Pub Inc, 2006. ISBN 978-0766025370

- Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons. McFarland, 2016. ISBN 978-0786479924

- Winkler, Peter (ed.). The Real James Dean: Intimate Memories from Those Who Knew Him Best. Chicago Review Press, 2016. ISBN 978-1613734728

External links

All links retrieved July 11, 2022.

- James Dean at the Internet Movie Database

- James Dean Oscars.org

- JamesDean.com

- James Dean Archives Seita Ohnishi Collection, Kobe Japan

- James Dean Find a Grave

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.