Jiandao

| Chinese name | |

|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 間島 |

| Simplified Chinese | 间岛 |

| Pinyin | Jiāndǎo |

| Wade-Giles | Chien-tao |

| Japanese name | |

| Kanji | 間島 |

| Hepburn Romaji | Kantō |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | 간도 |

| Hanja | 間島 |

| Revised Romanization | Gando |

| McCune-Reischauer | Kando |

Jiandao (間島), known in Korean as Gando, refers to northeastern parts of the People's Republic of China populated mostly by Koreans. The area, approximately 31,000 square kilometers in size, serves as home to about a million ethnic Koreans.[2] Jiandao Province (間島省) constituted one of the provinces of Manchukuo, an Imperial Japanese puppet state in Manchuria during World War II with Yanji as its capital.

Today, most of the region resides in Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture, a part of Jilin Province of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The Chinaese call the region Yanbian (延邊 (Yenbyen 옌볜, or Yŏnbyŏn 연변 in Korean); they seldom use Jiandao due to the association with Japanese occupation. North Korea and South Korea recognize the region as a part of the People's Republic of China, but some groups in South Korea claim the region as a historical part of Korea.

The one million ethnic Koreans living in Jiandao draws the attention of South Koreans. North Korean popular opinion has no voice; the North Korean communist government has been on good terms with China, not seeking to loose China's support. A small number of South Koreans seek to have the issue of Korean or Chinese sovereignty over Jiandao reopened. They argue that the region resided within Korean boundaries until the colonization of Korea by Japan. Boundary discussions ended prematurely, requiring that they open again. The question remains ethnic Koreans living in Jiandao would support the return of the region to Korean sovereignty or whether they would prefer to remain in China.

History

Balhae to Joseon

Multiple kingdoms ruled the region throughout ancient times including Goguryeo and Balhae. Goguryeo (called Gaojuli by Chinese) belonged to the Three Kingdoms of Korea. Balhae (Bohai in Pinyin) existed in the area during the Tang Dynasty in China and the Unified Silla Period in Korea. China emphasizes that Balhae maintained a temporary tributary relationship with Tang, while Korea claims that Balhae represented a continuance Goguryeo.

The Khitan of the Liao Dynasty destroyed Balhae in 926, formally annexing the territory in 936. For the next several centuries the region changed hands between the Khitans, Jurchens, Mongols, and finally, the Manchus, whose Qing Dynasty succeeded in conquering China and forcing submission from the Joseon Dynasty in Korea.

In 1712, Qing and Joseon formally demarcated the border between China and Korea. For years, Qing officials prohibited Koreans from moving into Manchuria, reserving the region for the Manchu royalty to flee and retain a strong base to maintain control of China if a Han majority government rise again. Joseon officials also prohibited its subjects to move to Manchuria. Those governmental prohibitions, along with the general marshy nature of the area, left Gando undeveloped and sparsely inhabited for almost two centuries. By the late 19th century, significant numbers of Koreans moved into Manchuria, even more arriving as refugees when Korea became a colony of Japan in 1910. During that period, the interpretation of the 1712 boundary agreement became subject to dispute, as was Gando's ownership (see below).

Under Japanese colonial rule

In 1905, Japan incorporated the Korean Empire as a protectorate, effectively terminating Korea's diplomatic rights. In the early twentieth century, Korean immigration to Manchuria steadily increased from Koreans fleeing from Japanese rule in Korea and through Japan's policy to develop the region. Some Chinese local governments welcomed the Korean immigrants as they provided labor and agricultural skill. On April 18, 1906, the Japanese military invaded Gando declaring the region under Japan' rule. In the Gando Convention of 1909, Japan affirmed territorial rights of the Qing over Gando after the Chinese foreign ministry issued a thirteen-point refutation statement regarding its rightful ownership. The treaty also contained provisions for the protection and rights of ethnic Koreans under Chinese rule. Nevertheless, large Koreans settlements had been established in the area which effectively remained under Japanese rule.

Despite the agreement, Koreans in Gando continued to serve as a source of friction between the Chinese and Japanese governments. Japan considered all ethnic Koreans in the region Japanese nationals, subject to Japanese jurisdiction and law, and demanded rights to patrol and police the area. The Qing, and subsequent local Chinese governments, presumed territorial sovereignty over the region.[1]

After the Mukden Incident, on September 18, 1931, the Japanese military invaded and occupied Manchuria. Between 1931 to 1945, Manchuria remained under the control of Manchukuo, a Japanese client state with Jiandao as a province of Manchukuo. That period initiated a new wave of Korean immigration, as the Japanese government actively encouraged (or forced) Korean settlement to colonize and develop the region. After World War II and the liberation of Korea, many Korean expatriates in the region moved back, but a significant majority remained in Manchuria; descendants of those people form the Korean ethnic minority in China today. The area makes up the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture in Jilin province.

Boundary Treaty and Disputes

Agreement of 1712

Korean claims over Gando stem from an ambiguity in the original Sino-Korean boundary agreement. After several attempts by the Kangxi Emperor to negotiate the issue of sovereignty, in 1712 the Joseon of Korea and Qing of China agreed to delineate the boundaries of the two countries at the Yalu and Tumen Rivers. Mukedeng led the Qing delegation while Pak Kwon led the Joseon delegation. The two ambassadors led a joint commission to survey and demarcate the boundaries between the two states. The commission made efforts to locate the sources of the Yalu and Tumen rivers at Mt. Paektu (Baitou). Owing to Pak's advanced age, they agreed for Mukedeng's team to ascend the summit alone. Mukedeng's team quickly identified the source of the Yalu, but identification for the Tumen proved more complicated. After considerable difficulty, the Qing team designated a source, erecting a stele as a boundary marker. Over the next year, the Qing built a fence to demarcate the areas where the Tumen river ran underground.

The Joseon government instructed Pak Kwon to retain all territory south of the Yalu and Tumen rivers, a goal he accomplished. Some Korean officials lamented the loss of claims on areas north of the river and criticized Pak Kwon for not accompanying Mukedeng to the summit. The territorial claims stem from the territories held by Goguryeo and Bohai, ancient states in Manchuria from which Koreans claimed heritage. The border remained uncontentious for the next 150 years. The two governments prohibited cross-border movements, punishable by death after detaining trespassers who were repatriated back to their respective countries.

Qing's 1870s Revision of Treaty

In the 1870s the Qing government reversed its policy of prohibiting entry to Manchuria, and began allowing Han Chinese settlers into the territory in response to growing Russian encroachment. The area around Gando opened to settlement in 1881, but Chinese settlers quickly discovered some Korean farming communities already established in the area. Despite the decreed punishment, severe droughts in northern Korea motivated Korean farmers to seek new lands. The Jilin general-governor Ming-An's official responded by lodging a protest to the Joseon government, offering to allow the Korean population to stay if they agreed to become Manchu subjects and adopt Qing customs and dress. Joseon respond by encouraging the farmers not to register as Qing subjects but to return to Korea within the year.

The border did not become a bone of contention again until almost 150 years later—the second moment pointed out in Chang Chiyon’s work. In the 1870s Qing authorities began to open Manchuria, shut off from Han migration since the earliest years of the dynasty. In various stages between 1878 and 1906 the entire expanse of Manchuria opened to settlement; the Tumen River valley received its first legal Han settlers in 1881. When these Qing settlers arrived, however, they quickly discovered that many more Koreans had already begun farming much of the best land. By 1882 the presence of large Korean communities in the region came to the attention of the general of Jilin, Ming An, who proceeded to lodge a protest with the Choson court, laying down a number of conditions: so long as these Koreans paid taxes to the court, registered their households with local authorities, recognized the legal jurisdiction of the Jilin authorities, and shaved their heads in the Manchu style—in short, become Qing subjects—they were welcome to stay; otherwise they should return to Choson territory. Seoul responded by urging Ming An not to register their subjects, for within one year they would all be returned home—an agreement that seemed to accept Qing land claims. For the farmers themselves—people who had fled famine conditions and labored for more than ten years to bring land under cultivation—a move off the lands hardly proved a favorable scenario. Few left. By April of the following year the head of the Huichun Resettlement Bureau had again demanded of local Choson authorities that by the conclusion of the fall harvest the farmers be returned to the other side of the river.[2]

*Satellite view of same location; Baekdu Mountain, Lake Tianchi, and the Tumen River are visible

The farmers, unwilling to abandon their homes, argued owing to the ambiguity in the naming of the Tumen river, they actually resided in Korean territory. The Yalu (鴨綠) / Amnok (압록) River boundary has been firmly established, but the interpretation of the Tumen River boundary 土門 (토문) raises contention. The name of the river itself originates from the Jurchen word tumen, meaning "ten thousand." The official boundary agreement in 1712 identified the Tumen river using the characters 土門 (pinyin:tǔmen) for the phonetic transcription. The modern Tumen River is written as 圖們 (pinyin:túmen) in modern Chinese and as 豆滿 (두만) "Duman" in both modern Korean and Japanese. Some Koreans hence claim that the "Tumen" referred to in the treaty is actually a tributary of the Songhua River. Under that interpretation, Gando (where the Koreans settled) would be part of Korean territory.

Their position centered on an interpretation of the stele erected by Mukedeng more than two centuries earlier. The farmers contended that they had never crossed any boundary and were in fact within Choson territory. Their argument skillfully played off the ambiguity surrounding the character engraved on the stele to represent the first syllable in the name of the Tumen River. They argued that Qing officials had failed to distinguish between two different rivers, both called something like Tumen but written with a different character signifying the first syllable. One, the character on the stele, indicated earth; the second, a character not on the stele, signified what today is considered the tu for Tumen River, meaning diagram. The river behind which the Qing officials demanded the farmers withdraw was the latter. As argued by the farmers, though the pronunciation was nearly identical, the different characters signified two distinct rivers. The first Tumen River delineated the northernmost extreme of Choson jurisdiction, while a second Tumen River flowed within Choson territory. Qing authorities mistakenly believed the two rivers were one and the same, the petition suggested, only because Chinese settlers had falsely accused the Korean farmers of crossing the border. In fact their homes were between the two rivers, meaning that they lived inside Choson boundaries. The way to substantiate their claims, they urged, was to conduct a survey of the Mt. Paektu stele, for in their opinion the stele alone could determine the boundary.[3]

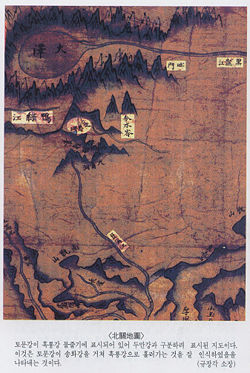

That confusion arouse as the two names sound identical, and neither name derives from the Chinese language. The two rivers from the period appear in a map reproduced to the right. Korean claims based on maps that show separate "Duman" and "Tumen" rivers. Geographers express uncertainty which modern river the Korean claim corresponds to, as no modern tributary of the Songhua River exists today with that name:

Satellite view of the Songhua river and Baekdu Mountain, for comparison purposes

Late Joseon Policy on Border

That interpretation of the boundary gradually developed into Joseon official policy. O Yunjung, a Korean official appointed to review the claims made by the farmers and investigate the sources of the river, adopted the latter interpretation and declared that the region belonged to Korea, not China. Joseon and Qing officials met in 1885 and 1887 to resolve the dispute, but with little progress. Korean officials suggested on starting from the stele and tracing the river downwards, while Qing officials proposed starting at the mouth of the Tumen River and moving upstream.

At this time O Yunjung, who later became a famous reform official, was appointed as special inspector for the Northwest. Upon receiving his appointment, O informed the king in wonderful Confucian rhetoric that the farmers would “naturally return” as they learned of the king’s sagely virtue, but when he arrived at the frontier, he quickly learned sagely virtue was no match for land. He immediately heard the complaints of the farmers. In response, O undertook two investigations, the first to verify the position and text of the Mt. Paektu stele, the second to ascertain the sources of the river. The results of these efforts sufficiently confirmed the position of the farmers, and O, in an audience at court, confidently eased the king’s doubt about their claim to these lands. “That these lands are not the lands of China,” he stated, “is most clear.” From this point what had been a view circulating only at the local level among residents developed into official policy. By 1885 and 1887, when Choson and Qing delegates met along the border to survey the local topography with the hope of ending the disagreement, the Choson negotiators had adopted the interpretation of the stele as the basis of their negotiating stance. Start at the stele, they told their Qing counterparts, and trace the river downward from this point. The Qing side rejected this emphasis on the stele. Instead, the opposite method of locating the border was suggested: start at the mouth of the Tumen River and trace the river upstream, regardless of the positioning of the stele. A number of surveys were conducted, but more accurate information on the local topography did little to soften the opposing positions on determining the boundary.[4]

From 1905 onwards, Japan seized control of Korea effectively ending the endeavor to settle the dispute.

Post-1945 Liberation

After liberation of Korea in 1945, many Koreans believed that Gando should be given to Korean rule, but the military control by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in the north hindered claims to the territory. The chaos of the Korean War and the geopolitical situation of the Cold War effectively thwarted any opportunity for Koreans to highlight the Gando issue. In 1962, North Korea signed a boundary treaty with People's Republic of China setting the Korean boundary at Yalu and Tumen, effectively foregoing territorial claims to Gando. South Korea also recognizes that as the boundary between Korea and China.

Today, none of the governments involved (North Korea, South Korea, People's Republic of China, or Japan) claim Gando as Korean territory. The Korean minority in China shows little or no interest for irredentism. Although occasional disputes erupt between Korean and Chinese scholars over historical interpretation, the issue arouses little or no official interest on the part of any of the parties, and relations between China and both Koreas remain warm. In 2004 the South Korean government issued a statement to the effect that it believed the Gando Convention null and void. The resultant controversy and strong negative reaction from the PRC led to a retraction of the statement, along with an explanation by the Korean government that the retraction arose from an "administrative error."

A small number of South Korean activists believe that under a unified Korea, the treaties signed by North Korea can be deemed null, allowing the unified Korea to actively seek regress for Gando. The current political situation makes that a faint possibility at best. Some scholars claim that China's efforts to incorporate the history of Goguryeo and Balhae into Chinese history serves effectively as a pre-emptive move to squash any territorial disputes that might rise regarding Gando before a unified Korea can claim such or the Korean ethnic minority in the Manchuria region claim to become part of Korea.

Maps of Borders

Sino-Korean borders to be aligned along the Yalu and Tumen rivers

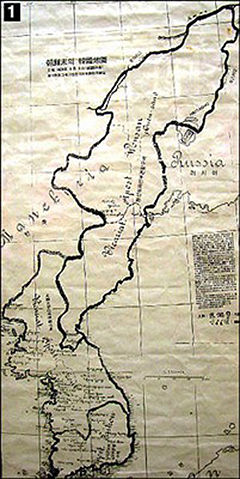

The following maps, made by Korea from the 1700s to the 1800s, show Sino-Korean borders to be aligned along the Yalu and Tumen rivers, essentially the same as those today:

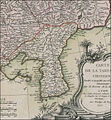

Maps From Western Sources

Korean claims to Gando are based on other maps. The following were made by western missionaries. However, the first is explicitly stated as a map of "Quan-Tong Province" (now Liaoning province, China) and Kau-li (Korea), and the second is stated as a map of the Chinese Tartary (la Tartarie Chinoise). Compared to the Korean-made maps above, the coastlines and rivers are also significantly less accurate; nor do these maps following the Sino-Korean border at the Yalu/Amnok River, which is not ambiguous:

Identical Maps with differences in border

Note that two almost identical versions of a first map exists, showing significant differences in the border. One shows the boundaries similar to modern-day province and country borders, while the other shows the Sino-Korean border significantly further north.

Roman Catholic Map

Some Koreans arguing for a restoration of Gando to Korea use the map (reproduced in the history section at the beginning of this article) published by the Roman Catholic Apostolic vicariates during the early 20th century to support Korean claim to the territory. At that time, the Roman Catholic church divided Korea into three Apostolic vicariates; Seoul (originally Corea established in 1831 by Pope Gregory XVI, Daegu in 1911 by Pope Pius X, and Wonsan in 1920 by Pope Benedict XV, which, as can be seen in the map, extended throughout both eastern Manchuria, including Gando, as well as northern Korea. Those arguing for Korean possession offer the map as proof that eastern Manchuria is "Korean," rather than the converse hypothesis that northern Korea is "Manchurian."

See also

- Gando Convention

- Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture

Notes

- ↑ Erik W. Esselstrom, "Rethinking the Colonial Conquest of Manchuria: The Japanese Consular Police in Jiandao, 1909–1937." Modern Asian Studies 39 2000): 39-75. [1] Retrieved April 6, 2008.

- ↑ Andre Schmid, "Looking North toward Manchuria." South Atlantic Quarterly 99 (1)(2000): 226-227

- ↑ Schmid, 227

- ↑ Schmid, 227-228

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Books

- Han, Rucheng. 1992. Jiandao leng mian wu. Changchun Shi: Shi dai wen yi chu ban she. (in Mandarin Chinese) ISBN 9787538704471

- International Crisis Group. 2006. Perilous journeys: the plight of North Koreans in China and beyond. ICG Asia report, no. 122. Seoul: International Crisis Group. OCLC: 76827085

- U. S. Dept. of State. 1962. China-Korea boundary. International boundary study, no. 17. Washington, D.C.: Geographer, Dept. of State. OCLC 12175193

Articles

- China. 1910. "Chinese-Japanese agreements." September 4, 1909. American Journal of International Law 4: 130-133. OCLC: 31313471

- Esselstrom, Erik W. 2005. "Rethinking the Colonial Conquest of Manchuria: The Japanese Consular Police in Jiandao, 1909-1937." Modern Asian Studies 39 (1):39-75. ISSN: 0026-749X OCLC: 89193218

- Hanʼguk Kando Hakhoe. 2004. "Kando hakpo." Sŏul-si: Hanʼguk Kando Hakhoe. ISSN 1975-2709 OCLC 82394099

- Park, Hyun Ok. 2000. "Korean Manchuria: The Racial Politics of Territorial Osmosis." South Atlantic Quarterly 99 (1): 193-215. ISSN 0038-2876 OCLC 88652657 [3] (abstract) Project Muse (restricted access) Retrieved April 6, 2008.

- Schmid, Andre. "Looking North toward Manchuria." South Atlantic Quarterly 99 (1)(2000): 219-240. ISSN: 0038-2876 OCLC: 88652673

[4] (abstract) Project Muse (restricted access) Retrieved April 6, 2008.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.