Johannes Vermeer

Johannes Vermeer or Jan Vermeer (baptized October 31, 1632, died December 15, 1675) was a Dutch painter who specialized in scenes of ordinary people going about their everyday life. Using minute details he conveys subtle symbolic and allegoric themes that draw the viewer into the same state of deep contemplation that the figure(s) in his paintings convey. He was also a master at depicting the way light illuminates objects.

Virtually forgotten for nearly two hundred years, the art critic W. Thore-Burger resurrected interest in Vermeer in 1866 when he published an essay attributing 66 pictures to him (only 35 paintings are definitively attributed to him today). Even in his lifetime he was relatively unknown outside of his hometown of Delft where all of his works were painted. Now he has become one of the most admired artists of the Golden Age of Dutch Art.

In recent years a resurgence of appreciation for Vermeer's work can be seen in popular culture. For example, his painting Girl With a Pearl Earring along with others, have given rise to a series of fictionalized novels.

Early life

Johannes Vermeer was born in 1632, in the city of Delft in the Netherlands. The precise date of his birth is unknown but it is known that he was baptized on October 31, 1632, in the Reformed Church in Delft.

Vermeer's father, Reynier Vermeer,[1] was a lower middle-class silk weaver and an art dealer. He married Johannes' mother, Digna, a woman from Antwerp, in 1615. The Vermeer family bought a large inn, the "Mechelen" named after the homonymous Belgian town, near the market square in Delft in 1641. Reynier Vermeer probably served as inn-keeper while also acting as an art dealer.

After his father's death in 1652, Johannes Vermeer inherited the Mechelen as well as his father's art-dealing business.

Marriage and family

Despite the fact that he came from a Protestant family, he married a Catholic, Catherina Bolnes, in April 1653. Vermeer may have converted to Catholicism shortly before their marriage, a conversion suggested by the fact that some of his children were named after Catholic saints. His painting The Allegory of Faith reflects a Catholic belief in the Eucharist.[2]

Some after their marriage, the couple left the Mechelen and moved in with Catherina's mother, Maria Thins, a well-off widow, in a house in the "Papist corner" of town, where Catholics lived in relative isolation. Vermeer would live in his mother-in-law's house with his wife and children for the rest of his life.

Maria apparently played an important role in their life, for they named their first daughter after her, and it is possible that she used her comfortable income to help support the struggling painter and his growing family. Maria Thins was a devotee of the Jesuit order in the Catholic Church, and this, too, seems to have influenced Johannes and Catherina, for they called their first son Ignatius, after the founding saint of the Jesuit Order.

Johannes and Catherina had 14 children in total, three of whom predeceased Vermeer.

Career

It is generally believed that Vermeer apprenticed as a painter in Delft and that his teacher was either Carel Fabritius (1622 - 1654) or Leonaert Bramer (1596 - 1674).[3] Early paintings reflect the influence of the Utrecht Caravaggisti, a group of seventeenth century Dutch painters strongly influenced by the Italian artist Caravaggio.

On December 29, 1653, Vermeer became a member of the Guild of Saint Luke, a trade association for painters. The guild's records, which indicate that he could not initially pay the admission fee, suggest that Vermeer was of moderate means.

However, in later years his reputation, at least in his home town, solidified when one of Delft's richest citizens, Pieter van Ruijven, became his patron and bought many of his paintings. In 1662 he was elected head of the guild and was reelected in 1663, 1670, and 1671, evidence that he was considered an established craftsman among his peers.

Subsequently, a severe economic downturn was to strike the Netherlands in 1672 (the "Rampjaar," translated "the disaster year"), when the French invaded the Dutch Republic in what was later known as the Franco-Dutch War. This led to a collapse in demand for luxury items such as paintings, and consequently damaged Vermeer's business both as a painter and an art dealer.

When Johannes Vermeer died in 1675, he left Catherina and their children with very little money and several debts. At the time of his death eight of his eleven children were still minors. In a written document his wife attributed her husband's death to the stress of financial pressures. Catherina asked the city council to take over the estate, including paintings, in order to pay off the debts. The Dutch microscopist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, who worked for the city council, was appointed trustee for the estate in 1676. Nineteen of Vermeer's paintings were bequeathed to Catherina and Maria and some of these were sold to pay creditors.

Vermeer's relatively short life, - he was only 43 years of age when he died - coupled with the demands of his two careers, and his extraordinary precision as a painter all help to explain his limited output.

Technique

Vermeer produced transparent colors by applying paint onto the canvas in loosely granular layers, a technique called pointillé (not to be confused with pointillism). TIME magazine art critic Robert Hughes wrote about his technique,

"Vermeer had developed a unique way of rendering light and texture. Instead of building up forms with continuous movements of the brush, he used tiny luminous highlights, pasty dots and spots bringing more dissolved areas of light into focus. These gave a startling effect of studied, textural distinctness. It's as though you see every crumb in a cut loaf, every thread in a tapestry.[4]

There is no other seventeenth century artist who employed the expensive pigment lapis lazuli, also called natural ultramarine, so abundantly. Not only did he use it in elements that are intended to be shown as blue, like a woman’s skirt, a sky, the headband on the Girl with a Pearl Earring (The Hague), and in the satin dress of his later A Lady Seated at a Virginal (London), Vermeer also used the lapis lazuli widely as underpaint. For example, one can see it in the deep yet murky shadow area below the windows in The Music Lesson (London). For the wall beneath the windows - areas in these paintings of intense shadow - Vermeer composed by first applying a dark natural ultramarine, thus indicating an area void of light. Over this first layer he then scumbled varied layers of earth colors in order to give the wall a certain appearance: the earth colors umber and ochre should be understood as warm light from the strongly lit interior, reflecting its multiple colors back onto the wall.[5]

This method was most likely influenced by Leonardo da Vinci’s observations that the surface of every object partakes of the color of the adjacent object.[6] In other words, no object is ever seen entirely in its natural color; likewise shadows are not merely black voids of darkness but reflect color as well.

An even more remarkable use of natural ultramarine is in The Girl with a Wineglass (Braunsweig). The shadows of the red satin dress are underpainted in natural ultramarine, and due to this underlying blue paint layer, the red lake and vermilion mixture applied over it acquires a slightly purple, cool and crisp appearance that is very effective.

Camera Obscura

Artists of that era regularly used a camera obscura - the forerunner to the camera - to trace images for their paintings. Since there is no documented record of any drawings done by Vermeer it is impossible to conclude how much he relied upon this technique. However, it is fair to speculate that in Delft - a center for optical experimentation and lens making - this was a relied upon method. The use of the camera obscura is controversial with at least one artist, (see modern artist David Hockney's Hockney-Falco thesis).

Regardless of his use of the camera obscura to paint perspective, Vermeer was undisputed as a master of creating realistic effects. American Artist magazine writer Terry Sullivan said of the painting Little Street in Delft, "As with almost any masterpiece, if you cover up one shape, small or large, the whole work seems to crumble… With only minimal use of atmospheric and scientific perspective, Vermeer created not only an illusion of space but an unforgettable image of an orderly world expressed through architecture, human gestures, and control of the paint itself."[7]

Themes

Vermeer's works are largely genre pieces and portraits, with the exception of two cityscapes, one of them View of Delft, his largest work.

His subjects offer a cross-section of seventeenth century Dutch society, ranging from the portrayal of a simple milkmaid at work, to the luxury and splendor of rich notables and merchantmen in their stately houses.

In the 1660s Vermeer painted a series of paintings with a musical theme including, Girl Interrupted at Her Music. Her image, visible in the mirror above her head, is another indicator of Vermeer's experimentation with optical effects. Other paintings from this time period include: Lady and Gentleman at the Virginal and The Concert. The mood captured through these paintings is one of measure and harmony, as serene and peaceful as the subject matter itself.

Many of Vermeer's paintings have as their theme letter writing. It is believed that Young Lady in Blue Reading a Letter may have been his wife as the woman in the picture is pregnant and it is highly likely in that era that it only be considered proper etiquette for a wife to pose for her husband. It is believed she is in other works, as well, such as Woman with a Balance, which is said to have religious implications due to its symbolic arrangement of objects including the picture of the Last Judgment in the background. Other religious and scientific connotations can be found in his works. In his painting Allegory of Faith the personification of faith takes communion before a painted crucifixion. An apple (signifying original sin) and a snake crushed by a stone (emblematic of the victory of Christ, the cornerstone of the church, over Satan) lie at her feet. [8]

The Astronomer and The Geographer are the only two works featuring men, and careful display of objects such as maps, charts, and books conveys a feeling of reverence for the subject matter.

Legacy

By the 1920s, the commercial value of Vermeer's paintings increased dramatically. In 1925, the Girl with a Red Hat was discovered in a Paris collection. "The excitement surrounding this discovery, widely reported by the press, was repeated only two years later with yet two more discoveries of "Vermeer" paintings: The Lacemaker and the Smiling Girl. Both paintings were forgeries. Both had been bought (from the art dealers Duveen Brothers) by one of the most important American collectors, Andrew Mellon. The forger of these "Vermeer's," was a Dutchman by the name of Theo van Wijngaarden.[9]

Another famous forger was Han van Meegeren, also a Dutch painter who, initially seeking to prove that critics had underestimated his abilities as a painter, decided to paint fakes that were attributed to Vermeer (and others as well). His first Vermeer forgery, Lady and Gentleman at the Spinet was produced in 1932.[10] Van Meegeren fooled the art establishment, and was only taken seriously (as a forger) after demonstrating his skills in front of police witnesses in a court of law. His aptitude at forgery shocked the art world and complicated efforts to assess the authenticity of works attributed to Vermeer.[4]

Vermeer's Lady Writing a Letter With Her Maid was stolen from Russborough House in Ireland in 1986. Then in 1990, 13 valuable works of art were stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, including Vermeer's The Concert. [11]In 1993 Lady Writing a Letter With Her Maid was recovered but The Concert is still missing as of 2007 even though a $5 million dollar reward has been offered.

Vermeer and his works have featured in a number of novels, poetry, and other media in popular culture:

- Tracy Chevalier wrote a popular novel in 1999 titled "Girl with a Pearl Earring," which looks into one possible origin for the famous Vermeer painting of the same name. Peter Webber's 2003 film "Girl with a Pearl Earring" is an adaptation of Chevalier's bestselling novel, starring Scarlet Johansson and Colin Firth.

- George Bowering, the first Canadian poet laureate, wrote a book of poetry titled Vermeer’s Light: Poems 1996-2006 that was published in 2006.

- Vermeer's View of Delft features in a pivotal sequence of Marcel Proust's The Captive.

- The liqueur Vermeer Dutch Chocolate Cream Liqueur was inspired by and named after Vermeer and its bottle is embossed with his signature and has a logo incorporating the Girl with a Pearl Earring.

- Salvador Dalí, who greatly admired Vermeer, painted him in The Ghost of Vermeer of Delft Which Can Be Used As a Table, 1934.

- The 2003 children's novel Chasing Vermeer by Blue Balliett describes the theft of A Lady Writing and has the authenticity of Vermeer's paintings as a central theme.

- Dutch composer Louis Andriessen based his opera, Writing to Vermeer (1997-1998, libretto by Peter Greenaway), on the domestic life of Vermeer.

- "Brush with Fate" was a made-for-TV film debuted on February 2, 2003, on CBS. It followed the life of an imaginary painting by Vermeer as it passes through the hands of various people.

- The book Girl, Interrupted (1993) by Susanna Kaysen and a film based on it take their title from the painting Girl Interrupted at her Music.

A New Yorker critic said of the renewed interest in his paintings, "I think that Vermeer's ideal was a classless, timeless truth that is returning to the fore in contemporary culture: the essential role that aesthetic pleasure must play in any seriously lived life."[4]

Works

Only three paintings are dated: The Procuress (1656, Dresden, Gemäldegalerie), The Astronomer (1668, Paris, Louvre), and The Geographer (1669, Frankfurt, Städelsches). Two pictures are generally accepted as earlier than The Procuress; both are history paintings, painted in a warm palette and in a relatively large format for Vermeer—Christ in the House of Mary and Martha (Edinburgh, National Gallery) and Diana and her Companions (The Hague, Mauritshuis).

After The Procuress almost all of Vermeer's paintings are of contemporary subjects in a smaller format, that have a cooler palette dominated by blues, yellows and greys. It is to this period that practically all of his surviving works belong. They are usually domestic interiors with one or two figures lit by a window on the left. They are characterized by a serene sense of compositional balance and spatial order, unified by an almost pearly light.

A few of his paintings show a certain hardening of manner and these are generally thought to represent his later works. From this period come The Allegory of Faith (c 1670, New York, Metropolitan Museum) and The Letter (c 1670, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum).

Today, 35 paintings are clearly attributed to Vermeer, and they are:

- Christ in the House of Martha and Mary (1654-1655) - Oil on canvas, 160 x 142 cm, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh

- Diana and Her Companions (1655-1656) - Oil on canvas, 98,5 x 105 cm, Mauritshuis, The Hague

- The Procuress (1656) - Oil on canvas, 143 x 130 cm, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

- Girl reading a Letter at an Open Window (1657) - Oil on canvas, 83 x 64,5 cm, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

- A Girl Asleep (1657) - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- The Little Street (1657/58) - Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

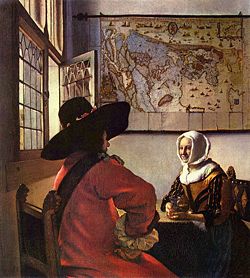

- Officer with a Laughing Girl (c. 1657) - Oil on canvas, 50,5 x 46 cm, Frick Collection, New York

- The Milkmaid (c. 1658) - Oil on canvas, 45,5 x 41 cm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

- A Lady Drinking and a Gentleman (1658-1660) - Oil on canvas, 39,4 x 44,5 cm,Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

- The Girl with the Wineglass (c. 1659) - Oil on canvas, Herzog Anton-Ulrich-Museum, Braunschweig

- View of Delft (1659-1660) - Oil on canvas, 98,5 x 117,5 cm, Mauritshuis, The Hague

- Girl Interrupted at her Music (1660-1661) - Oil on canvas, 39,4 x 44,5 cm, Frick Collection, New York

- Woman in Blue Reading a Letter (1663-1664) - Oil on canvas, 46,6 x 39,1 cm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

- The Music Lesson or A Lady at the Virginals with a Gentleman (1662/5) - Oil on canvas, 73,3 x 64,5 cm, Queen's Gallery, London

- Woman with a Lute near a Window (c. 1663) - Oil on canvas, 51,4 x 45,7 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Woman with a Pearl Necklace (1662-1664) - Oil on canvas, 55 x 45 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

- Woman with a Water Jug (1660-1662) - Oil on canvas, 45,7 x 40,6 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- A Woman Holding a Balance (1662-1663) - Oil on canvas, 42,5 x 38 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington

- A Lady Writing a Letter (1665-1666) - Oil on canvas, 45 x 40 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington

- Girl with a Pearl Earring (a.k.a. Girl In A Turban, Head Of Girl In A Turban, The Young Girl With Turban) (c. 1665) - Oil on canvas, 46,5 x 40 cm, Mauritshuis, The Hague

- The Concert (1665-1666) - Oil on canvas, 69 x 63 cm, stolen in March 1990 from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston[12]

- Portrait of a Young Woman (1666-1667) - Oil on canvas, 44,5 x 40 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- The Allegory of Painting or The Art of Painting (1666/67) - Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

- Mistress and Maid (1667/68) - Frick Collection, New York

- Girl with a Red Hat (1668) - National Gallery of Art, Washington

- The Astronomer (1668) - Louvre, Paris

- The Geographer (1668/1669) - Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt am Main

- The Lacemaker (1669/1670) - Louvre, Paris

- The Love Letter (1669/1670) - Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

- Lady writing a Letter with her Maid (1670) - Oil on canvas, 71,1 x 58,4 cm, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

- The Allegory of Faith (1671/1674) - Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- The Guitar Player (1672) - Iveagh Bequest Kenwood House, London

- Lady Standing at the Virginals (1673/1675) - National Gallery, London

- Lady Seated at the Virginals (1673/1675) - National Gallery, London

- Paintings by Vermeer, chronologically

Young woman sleeping (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) (1656-1657)

Officer and a Laughing Girl (Frick Collection, New York) (1657-1659)

The Milkmaid (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam) (c. 1658)

Woman in Blue Reading a Letter (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam) (after 1664)

Woman Holding a Balance (1665)[13]

The Loveletter (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam) (1670)

Notes

- ↑ Reynier Vermeer's name actually was Reynier Vos (Fox), but he used the name Van der Meer.

- ↑ Essential Vermeer Resources Essentialvermeer.com.Retrieved October 22, 2007.

- ↑ Vermeer biography, National Gallery of Art Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Jan Vermeer." Authors and Artists for Young Adults, Volume 46. (Detroit, MI: Gale Group, 2002).

- ↑ An Interview with Jørgen Wadum Essentialvermeer.20m.com. Retrieved October 22, 2007.

- ↑ B. Broos, A. Blankert, J. Wadum, A.K. Wheelock Jr. (1995) Johannes Vermeer. (Zwolle: Waanders Publishers)

- ↑ Terry Sullivan, quoted in "Jan Vermeer." Authors and Artists for Young Adults, Volume 46. Gale Group, 2002. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, MI: Thomson Gale. 2007)

- ↑ Johannes Vermeer Answers.com.

- ↑ False Vermeers Girl-with-a-pearl-earring.20m.com. Retrieved October 23, 2007.

- ↑ Han van Meegeren Denisdutton.com. Retrieved October 23, 2007.

- ↑ Documentary 'Stolen' Tracks Search for Lost Art, NPR. Retrieved October 22, 2007.

- ↑ Stolen, a documentary about the theft of The Concert, from the PBS website

- ↑ In-depth discussion of "Woman Holding a Balance" from the National Gallery of Art website

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- "Jan Vermeer." Authors and Artists for Young Adults, Volume 46. Gale Group, 2002. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, MI: Thomson Gale. 2007.

- Sheldon, Libby, and Nicola Costaros. "Johannes Vermeer’s ‘Young woman seated at a virginal’." The Burlington Magazine, February 2006, Number 1235, Volume CXLVIII.

- Schneider, Robert. Vermeer. Koln: Benedikt Taschen Verlag GmbH, 1993.

- Tansey, Richard G., and Fred S. Kleiner. Gardner's Art Through the Ages. Harcourt Brace, 1996. ISBN 0155011413

- Wadum, J. “Contours of Vermeer,” in Vermeer Studies. Studies in the History of Art. 55. Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, Symposium Papers XXXIII, eds. I. Gaskel and M. Jonker. Washington/New Haven: National Gallery Washington, 1998, 201-223.

Further Reading

- Arasse, Daniel, and Johannes Vermeer. 1994. Vermeer, Faith in Painting. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691033625

- Vermeer, Johannes, Frederik J. Duparc, and Arthur K. Wheelock. Johannes Vermeer. Washington,DC: National Gallery of Art, 1995. ISBN 0300065582

- Brusati, Celeste, and Johannes Vermeer. Johannes Vermeer. Rizzoli art series. New York, NY: Rizzoli International Publications, 1993. ISBN 0847816494

- Bailey, Anthony. Vermeer: A View of Delft. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Co., 2001. ISBN 0805067183

- Wheelock, Arthur K., and Johannes Vermeer. Vermeer the Complete Works. New York, NY: H.N. Abrams, 1997. ISBN 0810927519

- Wheelock, Arthur K. Vermeer & the Art of Painting. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995. ISBN 0300062397

External links

All links retrieved August 1, 2022.

- Essential Vermeer Essentialvermeer.com.

- Jan Vermeer Ibiblio.org.

- Rothstein, Edward. CONNECTIONS; Hidden in the Light of Vermeer's Window Nytimes.com. 2001.

- Haber, John. The Death of the Symbol Haberarts.com.

- Johannes Vermeer & life in Delft Xs4all.nl.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

_-_The_Girl_With_The_Pearl_Earring_(1665).jpg/84px-Johannes_Vermeer_(1632-1675)_-_The_Girl_With_The_Pearl_Earring_(1665).jpg)