Johannesburg

| Johannesburg | |||

| Johannesburg skyline with the Hillbrow Tower in the background | |||

|

|||

| Nickname: Joburg; Jozi; Egoli (Place of Gold); Gauteng (Place of Gold); Maboneng (City of Lights) | |||

| Motto: "Unity in development"[1] | |||

| Location of Johannesburg | |||

| Johannesburg location within South Africa | |||

| Coordinates: 26°12′S 28°3′E | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | |||

| Province | Gauteng | ||

| Established | 1886[2] | ||

| Government | |||

| - Mayor | Parks Tau (ANC)[3] | ||

| Area [4] | |||

| - City | 508.69 km² (196.4 sq mi) | ||

| - Metro | 1,644.96 km² (635.1 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 1,753 m (5,751 ft) | ||

| Population (2001 city; 2007 metro)[5] | |||

| - City | 1,009,035 | ||

| - Density | 2,000/km² (5,180/sq mi) | ||

| - Metro | 3,888,180 | ||

| - Metro Density | 2,364/km² (6,122.7/sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | SAST (UTC+2) | ||

| Area code(s) | 011 | ||

| Website: joburg.org.za | |||

Johannesburg is the largest and most populous city in South Africa, with nearly 3.9 million population in 2007. It is the provincial capital of Gauteng, the wealthiest province in South Africa, having the largest economy of any metropolitan region in Sub-Saharan Africa. Johannesburg is the source of a large-scale gold and diamond trade, due to its location on the mineral-rich Witwatersrand range of hills.

In the mid-twentieth century racial segregation in the form of apartheid came into play. From 1960 to 1980, several hundred thousand blacks were forced from Johannesburg to remote ethnic “homelands.” The 1970s and 1980s saw Johannesburg exploding in black discontent as racial injustices were openly committed. The African National Congress won South Africa's first multi-racial elections in 1994. After the Group Areas Act was done away with in 1991, along with the Land Act of 1913, thousands of poor, mostly black, people returned to the city from townships like Soweto, or flooded in from poor and war-torn African nations. Crime levels rose, especially the rate of violent crime. Landlords abandoned many inner city buildings, while corporations moved to suburbs like Sandton. By the late 1990s, Johannesburg was rated as one of the most dangerous cities in the world.

Although it is ranked as a top worldwide center of commerce, and is predicted to become one of the largest urban areas in the world, daunting problems remain. While black majority government has tipped the racial balance of power in Johannesburg, around 20 percent of the city lives in abject poverty in informal settlements that lack proper roads, electricity, or any other kind of direct municipal service. The lack of economic empowerment among the disadvantaged groups is linked to the poor uptake of education—35 percent of residents aged 20 and over have had only limited high school education.

It is a city of contrasts, of glass and steel high-rise buildings next to shantytowns, of world-class universities among widespread illiteracy, of extreme wealth and poverty.

Geography

Johannesburg is located in the eastern plateau area of South Africa known as the Highveld, at an elevation of 5,751 feet (1,753 meters). The former Central Business District is located on the south side of the prominent ridge called the Witwatersrand (Afrikaans: White Water's Ridge). The Witwatersrand marks the watershed between the Limpopo and Vaal rivers, and the terrain falls to the north and south. The north and west of the city has undulating hills while the eastern parts are flatter.

The city enjoys a dry, sunny climate, with the exception of occasional late afternoon downpours in the summer months of October to April. Temperatures are usually fairly mild due to the city's high altitude, with the average maximum daytime temperature in January of 79°F (26°C), dropping to an average maximum of around 61°F (16°C) in June. Winter is the sunniest time of the year, with cool days and cold nights. The temperature occasionally drops to below freezing at night, causing frost. Snow is rare. Mean annual precipitation is 28 inches (716 mm).

Johannesburg has over 10 million trees, many of which were planted in the northern areas of the city at the end of the nineteenth century to provide wood for mining. The areas were developed by the gold and diamond mining entrepreneur Hermann Eckstein, a German immigrant, who called the forest estates Sachsenwald. The name was changed to Saxonwold, now the name of a suburb, during World War I. Early white residents retained many of the original trees and planted new ones, although numerous trees were felled to make way for the Northern Suburbs' residential and commercial redevelopment.

Air pollution is a significant environmental issue in Johannesburg, especially in winter, when thermal inversions block air flow from the Indian Ocean. Pollution is worst in poor black townships on the outer ring of the city, where coal is used for fuel.

Johannesburg is a divided city, and its suburbs are the product of extensive urban sprawl. The poor mostly live in the southern suburbs, such as Soweto, a mostly black urban area constructed during the apartheid regime, or on the peripheries of the far north, as well as in the inner city.

Traditionally the northern and northwestern suburbs have been centers for the wealthy, containing the high-end retail shops as well as several upper-class residential areas such as Hyde Park, Sandhurst, Northcliff, and Houghton, the home of Nelson Mandela.

History

The region surrounding Johannesburg was inhabited by Stone Age hunter-gatherers known as Bushmen, or San. By the 1200s, groups of Nthu people began moving south from central Africa and encroached on the indigenous San population.

White trekboers, the semi-nomadic descendants of the predominantly Dutch settlers of Cape Town, started entering the area after 1860, escaping the English who controlled the cape since 1806, and seeking better pastures.

Gold discovered

Alluvial gold was discovered in 1853, in the Jukskei River north of Johannesburg by South African prospector Pieter Jacob Marais. Australian prospector George Harrison discovered gold at Langlaagte in 1886. Although he sold his claim and moved on, diggers flooded into the area, and discovered that there were richer gold reefs in the Witwatersrand.

Although controversy surrounds the origin of the city's name, one theory is that the new settlement was named after surveyors Johannes Meyer, and Johannes Rissik—the two men combined their common first name to which they added "burg," the archaic Afrikaans word for "village."

Johannesburg was a dusty settlement some 56 miles (90 km) from the Transvaal Republic capital Pretoria. As word spread, people flocked to the area from other regions of the country, and from North America, the United Kingdom and Europe. The gold attracted destitute white rural Afrikaners, and blacks from all over the continent, who worked in the mines on contract before returning home.

Babylon revived

By 1896, Johannesburg had a population of 100,000 people. The predominantly male population created the ideal location for liquor sales and prostitution, and attracted crime syndicates from New York and London, prompting a visiting journalist, in 1913, to write that "Ancient Ninevah and Babylon have been revived."

The amount of capital required to mine the low-grade deep gold deposits meant that soon the industry was controlled by half a dozen big mining houses, each controlled by a "randlord." As these randlords gained power, they became frustrated with what they perceived as a weak, corrupt Boer government.

Meanwhile, the British Empire was running low on currency reserves, and some British officials eyed control of the Johannesburg gold fields. A coup attempt against the Transvaal government failed in 1895, and in September 1899, the British government delivered an ultimatum, demanding the enfranchisement of all white British workers (uitlanders) there.

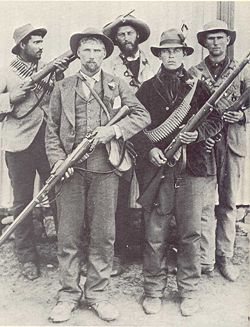

Boer War

This culminated in the South African War, fought from October 1899 to May 1902, between the British Empire and the two independent Boer republics of the Orange Free State and the South African Republic (Transvaal Republic). British troops entered Johannesburg in June 1900. The Boers lost, and control was ceded to the British. The new overlords rescinded Boer tariffs and passed a law designed to force blacks to accept work regardless of wages. Later, to increase a pool of cheap labor, imperial officials imported more than 60,000 Chinese indentured laborers.

Segregation was used as a means to deal with urban disorder. In 1904, blacks were relocated from the city center to Klipspruit, 10 miles to the southwest. The 1911 Mines and Works Act enshrined a “job colour bar.” The Natives (Urban Areas) Act of 1923 defined urban blacks as “temporary sojourners,” which enabled city authorities to relocate thousands of blacks from slums in the city to black townships. Police enacted pass and liquor raids to root out the “idle,” “disorderly,” or "superfluous."

Blacks organized petitions, and protest escalated to strikes by railway and municipal workers during World War I (1914-1918). The Transvaal Native Congress, a forerunner of the African National Congress, launched an anti-pass campaign. In 1920, 70,000 black mineworkers went on strike, only to be forced underground to work at bayonet point.

Rand rebellion

Mine-owners challenged white mineworkers in 1907, 1913, and 1922. The Rand Rebellion was an armed uprising of Afrikaans and English-speaking white miners in Witwatersrand, in March 1922, sparked by the mining companies’ intensified exploitation of the miners. The rebellion was eventually crushed by "considerable military firepower and at the cost of over 200 lives."

In the 1930s, South Africa's manufacturing industry outstripped the country's mining and agricultural industries, especially in Johannesburg, causing a big influx of blacks from the countryside seeking work. This influx increased when white workers left to fight in World War II (1939-1945), leaving booming factories desperate for manpower. Restrictions on black migration were lifted, and the city’s black population doubled to more than 400,000. Black migrants went to overcrowded townships or squatter camps. The squalid conditions bred disease and vice, but also sparked a new political consciousness and the emergence of the militant African National Congress Youth League, of which apprentice lawyer Nelson Mandela was a member. Black mineworkers went on strike in 1946.

Apartheid

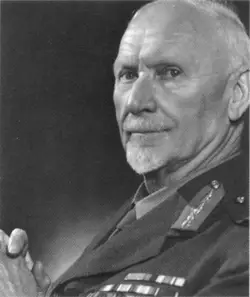

Racial segregation became the central issue of the 1948 election. Prime Minister Jan Smuts (1870-1950), of the United Party, argued that some permanent black urbanization was inevitable, while the National Party of Daniel F. Malan (1874-1959) warned that whites were being “swamped” and advocated a segregation policy called “apartheid.”

The National Party won, banned opposition parties, and during the next 46 years while it held power, introduced a series of laws, most notably the Group Areas Act of 1950, that specified where the races could live, work, or attend school. Pass laws were the main means of influx control—in 25 years, 10 million pass offenses were prosecuted in the state. From 1960 to 1980, several hundred thousand blacks were forced from Johannesburg to remote ethnic “homelands.”

Black discontent spreads

Black discontent exploded in Johannesburg on June 16, 1976, when South African police fired on a group of Soweto students protesting against plans to impose Afrikaans as a language of instruction in black schools. An uprising spread to 80 South African cities.

Johannesburg townships exploded again in 1984, when the National Party introduced limited franchise to Indians and coloureds (mixed race) while excluding the black majority. Unrest continued through the 1980s, accompanied by strikes.

Multi-racial elections

The African National Congress won South Africa's first multi-racial elections in 1994. After the Group Areas Act was scrapped in 1991, along with the Land Act of 1913, thousands of poor, mostly black, people returned to the city from townships like Soweto, or flooded in from poor and war-torn African nations. Crime levels rose, and especially the rate of violent crime. Landlords abandoned many inner city buildings, while corporations moved to suburbs like Sandton. By the late 1990s, Johannesburg was rated as one of the most dangerous cities in the world.

Drastic measures were taken to reduce crime (burglary, robbery, and assault) including closed-circuit television on street corners. Crime levels have dropped as the economy has stabilized and begun to grow. In an effort to prepare Johannesburg for the 2010 FIFA World Cup, local government has enlisted the help of former New York City mayor Rudolph Giuliani to help bring down the crime rate.

Government

South Africa is a republic in which the president is both the chief of state and head of government, and is elected by the National Assembly for a five-year term. The bicameral Parliament consists of the National Assembly of 400 members, and the National Council of Provinces of 90 seats. While Johannesburg is not one of South Africa's three capital cities, it does house the Constitutional Court—South Africa's highest court.

During the apartheid era, Johannesburg was divided into 11 local authorities, seven of which were white and four black or coloured. The white authorities were 90 percent self-sufficient from property tax and other local taxes, and spent US$93 per person, while the black authorities were only 10 percent self-sufficient, spending US$15 per person. The first post-apartheid Johannesburg City Council was created in 1995, and redistributed revenue from wealthy, traditionally white areas to help pay for services needed in poorer, black areas.

The city council was divided into four regions, each with a substantially autonomous local regional authority that was to be overseen by a central metropolitan council. Furthermore, the municipal boundaries were expanded to include wealthy satellite towns like Sandton and Randburg, poorer neighboring townships such as Soweto and Alexandra, and informal settlements like Orange Farm.

In 1999, Johannesburg appointed a city manager who, together with the Municipal Council, drew up a three-year plan that called upon the government to sell non-core assets, restructure certain utilities, and required that all others become self-sufficient. The plan took the city from near insolvency to an operating surplus of US$23.6-million.

Following the creation of the metropolitan municipality, Johannesburg was divided into 11 new regions (consolidated to seven in 2006) each of which contract to the central government to maximize efficiency. Each region is responsible for health care, housing, sports and recreation, libraries, social development, and other local community-based services, and each has a People's Centre where residents can lodge complaints, report service problems, and perform council-related business.

The mayor, chosen by the African National Congress's national executive office, takes ultimate responsibility for the city and leads a 10-person city council. The city management team implements city council decisions. The council's head office is the Metro Centre Complex in Braamfontein, which is responsible for overall administration, financial control, supply of services, and collection of revenues. The fire department and ambulances, the police and traffic control, museums, art galleries, and heritage sites are all controlled by separate departments within the central administration.

City councilors are either elected in one of Johannesburg's 109 electoral wards, or appointed by proportional representation from a party.

Economy

Johannesburg is a center of mining, manufacturing, and finance, and produces 16 percent of South Africa's gross domestic product. In a 2007 survey conducted by Mastercard, Johannesburg ranked 47 out of 50 top cities in the world as a worldwide center of commerce, the African city listed.

Mining was the foundation of the Witwatersrand's economy, but its importance has declined with dwindling reserves, and service and manufacturing industries have become more significant. The city's manufacturing industries ranges from textiles to specialty steels, and there is still a reliance on manufacturing for mining.

The service and other industries include banking, IT, real estate, transport, broadcast and print media, private health care, transport and a vibrant leisure and consumer retail market. Johannesburg has Africa's largest stock exchange, the JSE Securities Exchange. Due to its commercial role, the city is the seat of the provincial government and the site of a number of government branch offices, as well as consular offices and other institutions.

There is also a significant informal economy consisting of cash-only street traders and vendors. The Witwatersrand urban complex is a major consumer of water in a dry region. Its continued economic and population growth has depended on schemes to divert water from other regions of South Africa and from the highlands of Lesotho, the largest of which is the Lesotho Highlands Water Project, but additional sources will be needed early in the twenty-first century.

The city is home to several media groups which own a number of newspaper and magazine titles. The two main print media groups are Independent Newspapers and Naspers (Media24). The electronic media is also headquartered in the greater metropolitan region. Media ownership is relatively complicated with a number of cross shareholdings which have been rationalized in recent years resulting in the movement of some ownership into the hands of black shareholders. This has been accompanied by a growth in black editorship and journalism.

Johannesburg has not traditionally been known as a tourist destination, but the city is a transit point for connecting flights to Cape Town, Durban, and the Kruger National Park. Consequently, most international visitors to South Africa pass through Johannesburg at least once, which has led to the development of more attractions for tourists.

About 19 percent of economically active adults work in wholesale and retail sectors, 18 percent in financial, real estate and business services, 17 percent in community, social and personal services and 12 percent are in manufacturing. Only 0.7 percent work in mining.

Johannesburg is ranked 65th in the world, with a total GDP of US$79-billion, and second in Africa after Cairo.

Johannesburg, much like Los Angeles, is a young and sprawling city geared towards private motorists, and lacks a convenient public transportation system. One of Africa's most famous "beltways" or ring roads is the Johannesburg Ring Road.

The city's bus fleet consists of approximately 550 single and double-decker buses, plying 84 different routes in the city. Construction on a new Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system was under way in 2008. Johannesburg has two kinds of taxis, metered taxis, and minibus taxis, which are often of a poor standard in not only road-worthiness, but also in terms of driver quality.

Johannesburg's metro railway system connects central Johannesburg to Soweto, Pretoria, and most of the satellite towns along the Witwatersrand. However, the railway infrastructure covers only the older areas in the city's south. The Gautrain Rapid Rail was under construction in 2008.

Johannesburg is served by O.R. Tambo International Airport, the largest and busiest airport in Africa and a gateway for international air travel to and from the rest of southern Africa. Other airports include Rand Airport, Grand Central Airport, and Lanseria.

Demographics

The population of Johannesburg was 3,888,180 in 2007, while the population of the Greater Johannesburg Metropolitan Area was almost eight million. Johannesburg's land area of 635 square miles (1,645 square kilometers) gives a population density of 6,123 per square mile (2364 per square kilometer).

Johannesburg and Pretoria are beginning to act as one functional entity, forming one megacity of roughly 10 million people. The city is one of the 40 largest metropolitan areas in the world, it is one of Africa's only two global cities, the other being Cairo, according to the Globalization and World Cities group's 1999 inventory.

According to the State of the Cities Report, the cities of Johannesburg, Ekurhuleni (the East Rand) and Tshwane (greater Pretoria) will have a population of some 14.6 million people by 2015, making it one of the largest cities in the world.

People who live in formal households in Johannesburg number 1,006,930, of which 86 percent have a flush or chemical toilet, 91 percent have refuse removed at least once a week, 81 percent have access to running water, and 80 percent use electricity. About 66 percent of households are headed by one person.

Black Africans account for 73 percent of the population, followed by whites at 16 percent, coloreds at six percent and Asians at four percent. About 42 percent of the population is under the age of 24, while 6 percent of the population is over 60 years of age. A substantial 37 percent of city residents are unemployed, of which 91 percent are black. Women comprise 43 percent of the working population.

The poor are mostly black, and earn less than US$3194 per annum. The wealthy are mostly white. Around 20 percent of the city lives in abject poverty in informal settlements that lack proper roads, electricity, or any other kind of direct municipal service.

Regarding languages, 34 percent of Johannesburg residents speak Nguni languages at home, 26 percent speak Sotho languages, 19 percent speak English, and 8 percent speak Afrikaans.

Regarding religion, 53 percent belong to mainstream Christian churches, 24 percent are not affiliated with any organized religion, 14 percent are members of African Independent Churches, three percent are Muslim, one percent are Jewish and one percent are Hindu.

Johannesburg has a well-developed higher education system of both private and public universities. Johannesburg is served by the public universities the University of the Witwatersrand, famous as a center of resistance to apartheid, earning it the nickname "Moscow on the Hill," and the University of Johannesburg.

About 14 percent of the population have received higher education (University or Technical school), 29 percent of adults have graduated from high school, 35 percent have some high school education, 15 percent have primary education, and 7 percent are illiterate.

Society and culture

The Cradle of Humankind UNESCO World Heritage Site is 16 miles (25 km) to the northwest of the city. The Sterkfontein fossil site is famous for being the world's richest hominid site and produced the first adult Australopithecus africanus and the first near-complete skeleton of an early Australopithecine.

The city has the Johannesburg Art Gallery, which features South African and European landscape and figurative paintings. The Museum Africa covers the history of the city of Johannesburg, and has a large collection of rock art. There is the Mandela Museum, which is located in the former home of Nelson Mandela, the Apartheid Museum, and the Hector Pieterson Museum.

There is a large industry centered around visiting former townships, such as Soweto and Alexandra. The Market Theatre complex attained notoriety in the 1970s and 1980s, by staging anti-apartheid plays, and has now become a center for modern South African playwriting.

Gold Reef City, a large amusement park to the south of the Central Business District, is a large draw-card, and the Johannesburg Zoo is also one of the largest in South Africa.

Johannesburg's most popular sports are association football, cricket, rugby union, and running.

Looking to the future

Although Johannesburg is ranked as a top worldwide center of commerce, and is predicted to be one of the largest urban areas in the world, daunting problems remain, largely as a result of 100 years of racial policies that have blocked black progress.

A substantial 37 percent of city residents are unemployed, of which 91 percent are black. An epidemic of burglaries, robberies and assaults meant that by the late 1990s, Johannesburg was rated as one of the most dangerous cities in the world, causing many of its downtown hi-rise offices to be vacated.

While black majority government has tipped the racial balance of power, around 20 percent of the city lives in abject poverty in informal settlements that lack proper roads, electricity, or any other kind of direct municipal service.

The lack of economic empowerment among the disadvantaged groups is linked to the poor uptake of education—35 percent of residents aged 20 and over have received only limited high school education, 15 percent have only primary education, and 7 percent are illiterate.

Preparations for the 2010 FIFA World Cup have set the city a crime-reduction goal. It would be in its best interest to also set goals on improving public transport, electricity supply, medical care, and housing, all of which can provide the much-needed employment in addition to improving the lives of its citizens.

Notes

- ↑ Johannesburg (South Africa). Crwflags.com. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ↑ Chronological order of town establishment in South Africa based on Floyd (1960:20-26) pp. xlv-lii. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ↑ City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality. Gauteng Department of Local Government. Retrieved September 29, 2008.

- ↑ Municipal Demarcation Board, South Africa Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ↑ Census 2001—Statistics for Main Place Retrieved April 24, 2012.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beavon, Keith Sidney Orrock. 2004. Johannesburg: The Making and Shaping of the City. Imagined South Africa. Pretoria: University of South Africa Press. ISBN 9781868883035.

- Cartwright, Alan Patrick. 1965. The Corner House: The Early History of Johannesburg. Cape Town: Purnell. OCLC 3742920.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. Johannesburg. Retrieved August 17, 2008.

- Lange, Lis. 2003. White, Poor, and Angry: White Working Class Families in Johannesburg. Aldershot, Hampshire, England: Ashgate. ISBN 9780754609155.

- Meiring, Hannes, G.-M. Van der Waal, Wilhelm Grütter, and Anna Jonker. 1986. Early Johannesburg, its Buildings and its People. Cape Town: Human & Rousseau. ISBN 9780798114561.

- Nuttall, Sarah, and J.-A. Mbembé. 2004. Johannesburg: The Elusive Metropolis. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822366102.

- Rosenthal, Eric. 1970. Gold! Gold! Gold! The Johannesburg Gold Rush. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-949937-64-9.

- Tomlinson, Richard, et al. 2003. Emerging Johannesburg: Perspectives on the Postapartheid City. Routledge. ISBN 0415935598.

- Van Onselen, Charles, and Charles Van Onselen. 2001. New Babylon, New Nineveh: Everyday Life on the Witwatersrand, 1886-1914. Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball Publishers. ISBN 9781868421114.

External links

All links retrieved August 1, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Johannesburg history

- History_of_Johannesburg history

- City_of_Johannesburg_Metropolitan_Municipality history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

.jpg/250px-The_Wits_University_East_Campus_(archived).jpg)