John Muir

John Muir (April 21, 1838 – December 24, 1914) was one of the earliest and most influential American conservationists, sometimes called the Father of the National Park System. Muir's vision of nature as a treasured, God-given resource transcending its utilitarian value helped define the modern environmental and ecological movements. Muir warned against reckless exploitation of the natural world and emphasized the aesthetic, spiritual, and recreational value of wilderness lands.

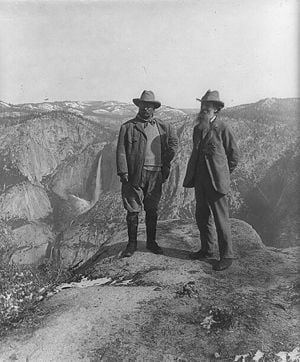

His letters, essays, and books telling of his adventures in nature were read by millions and are still popular today. His direct activism, including hosting of then President Theodore Roosevelt in the California backcountry, helped to save the Yosemite Valley and other wilderness areas. The Sierra Club, which he founded, remains a leading environmental organizations and influenced the establishment of numerous others.

Throughout his life, Muir was concerned with the protection of nature both for the spiritual advancement of humanity and as an affirmation of nature's inherent worth. He stressed human civilization's role as stewards of the environment, but more importantly the need to dwell harmoniously within the matrix of nature. "When we try to pick out anything by itself," Muir said, "we find it hitched to everything in the universe."

Biography

Early Life

John Muir was born in Dunbar, East Lothian, Scotland to Daniel and Ann Gilrye Muir. He was the third of eight children, being preceded by Margaret and Sarah and followed by David, Daniel, Ann and Mary (twins) and the American born Joanna. Daniel Muir was a grain merchant and a preacher with the Disciples of Christ. John's schooling and home life were both very strict but he found time to play games with other boys and to wander the countryside. He and his friends would sometimes run footraces for miles and miles.

The Muir family emigrated to the United States in 1849 and started a farm in Marquette County, Wisconsin; which was then wilderness. The whole family had to work very hard to help clear the land and run the farm. A lot of the responsibility fell to John as the oldest son, since his father was often away doing church work. He had a great interest in and love of nature and all living things. "Of the many advantages of farm life for boys," Muir wrote in his autobiography, The Story of My Boyhood and Youth,

- one of the greatest is the gaining a real knowledge of animals as fellow-mortals, learning to respect them and love them, and even to win some of their love. Thus godlike sympathy grows and thrives and spreads far beyond the teachings of churches and schools, where too often the mean, blinding, loveless doctrine is taught that animals have neither mind nor soul, have no rights that we are bound to respect, and were made only for man, to be petted, spoiled, slaughtered, or enslaved.

Muir was also interested in inventions and made several clocks, including one that triggered a mechanism to wake up a sleeper by tipping him out of bed. He was also a great reader, finding "inspiring, exhilarating, uplifting pleasure" in the poetry of the Bible, Shakespeare, and Milton.

In 1860, Muir left home and moved to Madison, Wisconsin. There he worked in a machine shop and later enrolled in the University of Wisconsin (which at been in existence for only 12 years at that time) studying various subjects, botany and geology being his favorites.

Muir was very disturbed by the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 and by the thought of so many of his friends going off to fight and maybe to die. He wrote a letter comparing the young soldiers to autumn leaves:

- They [the leaves] have done all that their Creator wished them to do, and they should not remain longer in their green vigor. But may the same be said of the slaughtered upon a battlefield? (Turner 1985)

Travels in Nature

In 1864, probably at least partly to avoid the possibility of being drafted into the army, Muir went to Canada. He spent most of his time there wandering the shores of the Great Lakes studying the plants. A letter he wrote telling of his discovery of a Calypso borealis, a species of orchid, was sent on to a newspaper and became his first published writing.

After the war, Muir returned to the United States and worked in a machine shop in Indianapolis, Indiana. He did well and made many improvements to the machinery and the operations of the shop. In March 1867, he was struck in the eye by a metal file while working on a machine. He lost the sight in both eyes for a time, and when he recovered his sight, he decided to leave the shop and devote himself to botany. An avid walker, Muir then undertook a thousand mile walk from Louisville, Kentucky to Savannah, Georgia. He planned to walk though the Southern States and then on to South America, but contracted malaria. When he recovered, he decided to put off the South America trip and go to California instead.

Arriving in San Francisco in March 1868, Muir immediately left for a place he had only read about, Yosemite. After seeing Yosemite Valley for the first time he was captivated, and wrote, "No temple made with hands can compare with Yosemite," and "[Yosemite is] the grandest of all special temples of Nature."

After his initial eight-day visit, he returned to the Sierra foothills and became a ferry operator, sheepherder, and bronco buster. In May 1869, a rancher named Pat Delaney offered Muir a summer job in the mountains to accompany and watch over Delaney's sheep and sheepherder. Muir enthusiastically accepted the offer and spent that summer with the sheep in the Yosemite area. That summer, Muir climbed Cathedral Peak, Mount Dana and hiked the old Indian trail down Bloody Canyon to Mono Lake. During this time, he started to develop his theories about how the area developed and how its ecosystem functioned.

Now more enthusiastic about the area than before, Muir secured a job operating a sawmill in the Yosemite Valley under the supervision of innkeeper James Hutchings. A natural born inventor, Muir designed a water-powered mill to cut wind-felled trees and he built a small cabin for himself along Yosemite Creek.

Pursuit of his love of science, especially geology, often occupied his free time and he soon became convinced that glaciers had sculpted many of the features of the valley and surrounding area. This notion was in stark contradiction to the accepted theory of the day, promulgated by Josiah Whitney (head of the California Geological Survey), which attributed the formation of the valley to a catastrophic earthquake. As Muir's ideas spread, Whitney would try to discredit Muir by branding him as an amateur. The premier geologist of the day, Louis Agassiz, however, saw merit in Muir's ideas, and lauded him as "the first man who has any adequate conception of glacial action."

In 1871, Muir discovered an active alpine glacier below Merced Peak, which further helped his theories to gain acceptance. Muir's former professor at the University of Wisconsin, Ezra Carr, and Carr's wife Jeanne encouraged Muir to publish his ideas. They also introduced Muir to notables such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, who later visited him in Yosemite, as well as many leading scientists such as Louis Agassiz, John Tyndall, John Torrey, Clinton Hart Merriam, and Joseph LeConte. With the Carrs' encouragement, Muir wrote and published a large number of essays and magazine articles, which were very well received by the public.

A large earthquake centered near Lone Pine, California in Owens Valley was felt very strongly in Yosemite Valley in March 1872. The quake woke Muir in the early morning and he ran out of his cabin without fear exclaiming, "A noble earthquake!" Other valley settlers, who still adhered to Whitney's ideas, feared that the quake was a prelude to a cataclysmic deepening of the valley. Muir had no such fear and promptly made a moonlit survey of new triggered rockslides created by earthquake. This event gave further support to Muir's ideas about the formation of the valley.

In addition to his geologic studies, Muir also investigated the Yosemite area's flora and fauna. He made two field studies along the western flank of the Sierra of the distribution and ecology of isolated groves of Giant Sequoia in 1873 and 1874. In 1876, the American Association for the Advancement of Science published a paper Muir wrote about the trees' ecology and distribution.

In 1880, Muir married Louisa Wanda Strentzel, whose parents owned a large ranch and fruit orchards in Martinez, a small town northeast of San Francisco. For the next ten years, he devoted himself to managing the family ranch, which became very successful. (When he died he left an estate of $250,000. The house and part of the ranch are now a National Historical Site.) During this time, two daughters were born, Wanda and Helen.

From studying to protecting

Muir's attention started to switch from studying the Yosemite area and Sierra to protecting it. A precipitating event for him was the discovery of a sign illegally claiming private ownership in Kings Canyon, and loggers cutting down ancient Giant Sequoia groves south of present day Sequoia National Park. Louisa Muir encouraged her husband to retire from managing the ranch so he could devote himself to his conservation work.

Muir threw himself into his new role with great vigor. He saw the greatest threat to the Yosemite area and the Sierras to be livestock, especially domestic sheep (calling them "hooved locusts"). In June 1889, the influential associate editor of Century magazine, Robert Underwood Johnson, camped with Muir in Tuolumne Meadows and saw firsthand the damage a large flock of sheep had done to the grassland. Johnson agreed to publish any article Muir wrote on the subject of excluding livestock from the Sierra high country. He also agreed to use his influence to introduce a bill to Congress that would make the Yosemite area into a national park, modeled after Yellowstone National Park.

A bill essentially following recommendations that Muir put forward in two Century articles ("The Treasure of the Yosemite" and "Features of the Proposed National Park," both published in 1890), was passed by Congress on September 30, 1890. To the dismay of Muir, however, the bill left Yosemite Valley in state control. With this partial victory under his belt, Muir helped form an environmental organization called the Sierra Club on May 28, 1892, and was elected as its first president (a position he held until his death 22 years later). In 1894, his first book, The Mountains of California, was published.

In July of 1896, Muir became good friends with another leader in the conservation movement, Gifford Pinchot. That friendship came to an abrupt end late in the summer of 1897 when Pinchot released a statement to a Seattle newspaper supporting sheep grazing in forest reserves. This philosophical divide soon expanded and split the conservationist movement into two camps. Muir argued for the preservation of resources for their spiritual and uplifting values; Pinchot saw conservation as a means of intelligently managing the nation's resources. Both men opposed reckless exploitation of natural resources, including clear-cutting of forests, and debated their positions in popular magazines, such as Outlook, Harper's Weekly, Atlantic Monthly, World's Work, and Century.

In 1899, Muir accompanied railroad executive E. H. Harriman on his famous exploratory voyage along the Alaska coast aboard a luxuriously refitted 250-foot steamer, the George W. Elder. He would later rely on his friendship with Harriman to apply political pressure on Congress to pass conservation legislation.

In 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt accompanied Muir on a visit to the park. Muir joined Roosevelt in Oakland for the train trip to Raymond. While the presidential entourage traveled by stagecoach into the park, Muir told the president about state mismanagement of the valley and rampant exploitation of the valley's resources. Even before they entered the park, he was able to convince Roosevelt that the best way to protect the valley was through federal control and management.

After entering the park and seeing the magnificent splendor of the valley, the president asked Muir to show him the real Yosemite and the two set off by themselves and camped in the backcountry. Around a fire, the visionary environmentalist and the nation's chief executive talked late into the night, slept in the brisk open air, and were dusted by a fresh snowfall in the morning—a night Roosevelt never would forget.

Muir then increased efforts by the Sierra Club to consolidate park management and was rewarded in 1905 when Congress transferred the Mariposa Grove and Yosemite Valley into the park.

Pressure then started to mount to dam the Tuolumne River for use as a water reservoir for San Francisco. The damming of Hetch Hetchy Valley was passionately opposed by Muir who called Hetch Hetchy a "second Yosemite." Muir, the Sierra Club, and Robert Underwood Johnson fought against inundating the valley and Muir even wrote Roosevelt pleading for him to scuttle the project. After years of national debate that polarized the nation, Roosevelt's successor, Woodrow Wilson signed the dam bill into law on December 19, 1913. Muir felt a great loss from the destruction of the valley, his last major battle.

Death and legacy

After a lifetime of wilderness adventures facing death on icy glaciers and remote cliffs, John Muir died quietly in Los Angeles on December 24, 1914 after contracting pneumonia. His legacy, however, lives on. Muir's books are still widely read and loved and present among the most passionate and eloquent descriptions of nature in the English language. The conservation movement that he helped found has profoundly transformed human awareness of the natural world and the need to protect its wonders. Remembering their travels together, Theodore Roosevelt wrote of John Muir:

- His was a dauntless soul... Not only are his books delightful, not only is he the author to whom all men turn when they think of the Sierras and Northern glaciers, and the giant trees of the California slope, but he was also—what few nature-lovers are—a man able to influence contemporary thought and action on the subjects to which he had devoted his life. He was a great factor in influencing the thought of California and the thought of the entire country so as to secure the preservation of those great natural phenomena—wonderful canyons, giant trees, slopes of flower-spangled hillsides—which make California a veritable Garden of the Lord. . . . Our generation owes much to John Muir.

Once asked why the mountains and valleys of the Alps are so highly developed with hotels, railways, and and encroaching urbanization, while in America the parklands relatively unencumbered by development, the mountaineer Rheinhold Messner explained the difference in three words: "You had Muir."

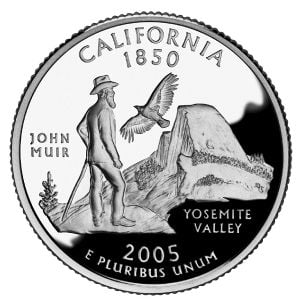

The John Muir Trail, the John Muir Wilderness, the Muir Woods National Monument, John Muir College (a residential college of the University of California, San Diego), and John Muir Country Park in Dunbar are named in his honor. An image of John Muir, with the California Condor and Half Dome, appears on the California state quarter which was released in 2005.

Quotes

- "Most people are on the world, not in it; have no conscious sympathy or relationship to anything about them, undiffused, separate, and rigidly alone like marbles of polished stone, touching but separate." (John Muir Information Guide - On People and the Wilderness)

- "Why should man value himself as more than a small part of the one great unit of creation? And what creature of all that the Lord has taken the pains to make is not essential to the completeness of that unit—the cosmos? The universe would be incomplete without man; but it would also be incomplete without the smallest transmicroscopic creature that dwells beyond our conceitful eyes and knowledge." (A Thousand Mile Walk to the Gulf)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ehrlich, G. 2000. John Muir: Nature's Visionary. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society. ISBN 0792279549

- Melham, Tom. 1976. John Muir's Wild America. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society.

- Meyer, J. M. 1997. “Gifford Pinchot, John Muir, and the boundaries of politics in American thought" Polity 30 (2): 267-284. ISSN: 0032-3497

- Miller, C. 2001. Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism. Island Press. New edition, 2004. ISBN 1559638230

- Muir, J. 1997 (original works 1894 to 1913). John Muir: Nature Writings: The Story of My Boyhood and Youth; My First Summer in the Sierra; The Mountains of California; Stickeen; Essays Library of America edition (edited by William Cronon).

- Smith, M. B. 1998. “The value of a tree: Public debates of John Muir and Gifford Pinchot.” Historian 60 (4): 757-778. ISSN: 0018-2370

- Turner, F. 1985. Rediscovering America, John Muir in His Time and Ours. ISBN 0871567040

- Wolfe, Linnie Marsh. 1945. Son of the Wilderness: The Life of John Muir. New York: Knopf. Second expanded edition, 2003. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0299186342

- Wuerthner, G. 1994. Yosemite: A Visitor's Companion. Stackpole Books. ISBN 0811725987

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.