Kalmyk people

| Kalmyks |

|---|

|

| Total population |

| Regions with significant populations |

| Kalmyks in Russia 178,000 Oirats in Mongolia: |

| Languages |

| Oirat |

| Religions |

| Tibetan Buddhism, Orthodox Christianity |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Khalkha-Mongolian, Buryat |

Kalmyk (alternatively "Kalmuck," "Kalmuk," "Calmouk," or "Kalmyki") is the name given to western Mongolian people and later adopted by those Oirats who migrated from Central Asia to an area around the Volga River in the seventeenth century. After the fall of the Yuan Dynasty in 1368, the West Mongolian people designated themselves “Dörben Oirat” ("Alliance of Four"), and engaged in nearly 400 years of military conflict with the Eastern Mongols, the Chinese and their successor, the Manchu, over domination and control of both Inner Mongolia and Outer Mongolia. In 1618, several tribes migrated to the grazing pastures of the lower Volga River region, where they eventually became a borderland power, often allying themselves with the Tsarist government against the neighboring Muslim population. They led a nomadic lifestyle, living in round felt tents called yurt (gher) and grazing their herds of cattle, flock of sheep, horses, donkeys and camels. Both the Tsarist government and, later, the Bolsheviks and Communists, implemented policies to eliminate their nomadic lifestyle and their religion, and eventually to eliminate the Kalmyks themselves. Their entire population was deported into exile during World War II. In 1957, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev permitted the Kalmyk people to return to their homes.

The Kalmyks are the only inhabitants of Europe whose national religion is Buddhism, which they embraced in the early part of the seventeenth century. Kalmyks belong to the Tibetan Buddhist sect known as the Gelugpa (Virtuous Way). Today they form a majority in the autonomous Republic of Kalmykia on the western shore of the Caspian Sea. Through emigration, Kalmyk communities have been established in the United States, France, Germany and the Czech Republic.

Origin of the name "Kalmyk"

"Kalmyk" is a word of Turkic origin meaning "remnant" or "to remain." Turkish tribes may have used this name as early as the thirteenth century. The Arab geographer Ibn al-Wardi is documented as the first person to refer to the Oirats as “Kalmyks” sometime in the fourteenth century[1]. The khojas of Khasgaria applied the name to Oirats in the fifteenth century[2]. Russian written sources mentioned the name "Kolmak Tatars" as early as 1530, and cartographer Sebastian Muenster (1488-1552) circumscribed the territory of the "Kalmuchi" on a map in his Cosmographia, which was published in 1544. The Oirats themselves, however, did not accept the name as their own.

Many scholars, including the Orientalist Peter Simon Pallas have attempted to trace the etymology of the name Kalmyk. Some have speculated that the name was given to the Oirats in an earlier period when they chose to remain in the Altai region while their Turkic neighbors migrated westward. Others believe the name may reflect the fact that the Kalmyks were the only Buddhists living in a predominantly Muslim region. Still others contend the name was given to those groups that did not return to their ancient homeland in 1771.

Location

The Kalmyks live primarily in the Republic of Kalmykia, a federal subject of Russia. [3]Kalmykia is located in the southeast European part of Russia, between the Volga and the Don Rivers. It has borders with the Republic of Dagestan in the south; the Stavropol Krai in the southwest; and the Rostov Oblast and the Volgograd Oblast in the west and the northwest, respectively. Its eastern border is the Astrakhan Oblast. The southeast border is the Caspian Sea.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, a large number of Kalmyks, primarily the young, moved from Kalmykia to larger cities in Russia, such as Moscow and Saint Petersburg, and to the United States, to pursue better educational and economic opportunities. This movement continues today.

Language

According to Robert G. Gordon, Jr., editor of the Ethnologue: Languages of the World, the Kalmyk-Oirat language belongs to the eastern branch of the Mongolian language division. Gordon further classifies Kalmyk-Oirat under the Oirat-Khalkha group, contending that Kalmyk-Oirat is related to Khalkha Mongolian, the national language of Mongolia.[4].

Other linguists, such as Nicholas N. Poppe, have classified the Kalmyk-Oirat language group as belonging to the western branch of the Mongolian language division, since the language group developed separately and is distinct. Moreover, Poppe contends that, although there is little phonetic and morphological difference, Kalmyk and Oirat are two distinct languages. The major distinction is in their lexicons. The Kalmyk language, for example, has adopted many words of Russian and Tatar origin and is therefore classified as a distinct language[5].

By population, the major dialects of Kalmyk are Torghut, Dörbet and Buzava [6]. Minor dialects include Khoshut and Olöt. The Kalmyk dialects vary somewhat, but the differences are insignificant. Generally, the dialects of the pastoral nomadic Kalmyk tribes of the Volga region show less influence from the Russian language.

In contrast, the Dörbets (and later on, Torghuts) who migrated from the Volga region to the Sal’sk District of the Don region and took the name Buzava (or Don Kalmyks), developed the Buzava dialect from their close interaction with Russians. In 1798 the Tsarist government recognized the Buzava as Don Cossacks, both militarily and administratively. As a result of their integration into the Don Host, the Buzava dialect incorporated many words of Russian origin.[7]

During World War II, all Kalmyks not fighting in the Soviet Army were forcibly exiled to Siberia and Central Asia, where they were dispersed and not permitted to speak the Kalmyk language in public places. As a result, the Kalmyk language was not formally taught to the younger generation of Kalmyks. Upon return from exile in 1957, the Kalmyks spoke and published primarily in Russian. Consequently, the younger generation of Kalmyks speak primarily Russian and not their own native language. Recent attempts have been made by the Kalmyk government to revive the Kalmyk language, such as passage of laws regarding the usage of Kalmyk on signs; for example, on entrance doors, the words 'Entrance' and 'Push-Pull' appear in Kalmyk. The attempt to re-establish the Kalmyk language has suffered setbacks. Recently, to reduce production costs, the Russian Broadcasting Corporation cut broadcast time allocated to Kalmyk language programs on radio and television, choosing instead to purchase pre-produced programs, such as English language productions.

Writing System

In the seventeenth century, Zaya Pandita, a Lamaist monk belonging to the Khoshut tribe, devised a script called Todo Bichig (clear script). The script, based on the classical vertical Mongol script, phonetically captured the Oirat language. In the later part of the nineteenth and early part of the twentieth centuries, todo bichig gradually fell into disuse and was abandoned by the Kalmyks in 1923 when the Russian Cyrillic alphabet was introduced. Soon afterwards, around 1930, Kalmyk language scholars introduced a modified Latin alphabet, which did not last long.

History

Origins

The Kalmyks are the European branch of the Oirats whose ancient grazing lands are now located in Kazakhstan, Russia, Mongolia and the People's Republic of China. The ancient forebears of the Oirats include the Keraits, Naimans, Merkits and the original Oirats, all Turko-Mongol tribes that roamed western Inner Asia prior to their conquest by Genghis Khan. According to Paul Pelliot, “Torghut,” the name of one of the four tribes who constituted the Oirats after the fall of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty, translates as garde du jour, suggesting that the Torghuts either served as the guard of Genghis Khan or, were descendants of the old garde du jour which existed among the Keraits, as recorded in the Secret History of the Mongols, before it was taken over by Genghis Khan[8].

After the Yuan Dynasty fell in 1368, the West Mongolian people designated themselves “Dörben Oirat” ("Alliance of Four"), an alliance was comprised primarily of four major Western Mongolian tribes: Khoshut, Choros, Torghut and Dörbet. Collectively, the Dörben Oirat sought to position themselves as an alternative to the Mongols who were the patrilineal heirs to the legacy of Genghis Khan. During their military campaigns, the Dörben Oirat frequently recruited neighboring tribes or their splinter groups, so that the composition of the alliance varied, with larger tribes dominating or absorbing the smaller ones. Smaller tribes belonging to the confederation included the Khoits, Zachachin, Bayids and Mangits. Turkic tribes in the region, such as the Urianhai, Telenguet and the Shors, also frequently allied themselves with the Dörben Oirat.

These tribes roamed the grassy plains of western Inner Asia, between Lake Balkhash in present-day eastern Kazakhstan and Lake Baikal in present-day Russia, north of central Mongolia, where they freely pitched their yurt (gher) and kept their herds of cattle, flock of sheep, [[horse]s, donkeys and camels. The Oirats emerged as a formidable foe against the Eastern Mongols[9], the Ming Chinese and their successor, the Manchu, in a nearly 400-year military struggle for domination and control over both Inner Mongolia and Outer Mongolia.

In 1757 the Oirats, the last of the Mongolian groups to resist vassalage to China, were exterminated in Dzungaria[10]. The massacre was ordered by the Qianlong Emperor, who felt betrayed by Prince Amursana, a Khoit-Oirat nobleman who submitted to Manchu authority on the condition that he be named Khan. After the death of the last Dzungar ruler, Dawa Achi, in 1759, the Qianlong Emperor declared an end to the Dzungar campaigns.

Period of Open Conflict

The Dörben Oirat, formed by the four major Oirat tribes, was a decentralized, informal and unstable alliance. The Dörben Oirat was not governed from a central location, and it was not governed by a central figure for most of its existence. The four Oirats did not establish a single military or even a unified monastic system, and did not adopt uniform customary laws until 1640.

As pastoral nomads, the Oirats were organized at the tribal level. Each tribe was ruled by a noyon (prince) who also functioned as the Chief Tayishi (Chieftain). The Chief Tayishi governed with the support of lesser noyons who were also called Tayisihi. These minor noyons controlled divisions of the tribe (ulus) and were politically and economically independent of the Chief Tayishi. The Chief Tayishi sought to influence and, in some cases, dominate the Chief Tayishis of the other tribes, causing inter-tribal rivalry, dissension and periodic skirmishes.

Under the leadership of Esen, Chief Tayishi of the Choros tribe, the Dörben Oirat unified Mongolia for a short period. After Esen's death in 1455, the political union of the Dörben Oirat dissolved quickly, resulting in two decades of Oirat-Eastern Mongol conflict. The deadlock ended when Eastern Mongol forces rallied during the reign of Dayan Khan (1464-1543), a direct descendant of Kublai Khan who was placed on the throne at the age of five. Dayan Khan took advantage of Oirat disunity and weakness and expelled them from eastern Mongolia, regaining control of the Mongol homeland and restoring the hegemony of the Eastern Mongols.

After the death of Dayan in 1543, the Oirats and the Eastern Mongols resumed their conflict. The Oirat forces thrust eastward, but Dayan's youngest son, Geresandza, was given command of the Eastern Mongol forces and drove the Oirats to Ubsa Nor in northwest Mongolia. In 1552, after the Oirats once again challenged the Eastern Mongols, Altan Khan swept up from Inner Mongolia with Tümed and Ordos cavalry units, pushing elements of various Oirat tribes from Karakorum to the Kobdo region in northwest Mongolia, reuniting most of Mongolia in the process [11].

The Oirats later regrouped south of the Altai Mountains in Dzungaria, but Geresandza's grandson, Sholui Ubashi Khong Tayiji, pushed them further northwest, along the steppes of the Ob and Irtysh Rivers. Afterwards, he established a Khalkha Khanate under the name, Altan Khan, in the Oirat heartland of Dzungaria. The Oirats continued their campaigns against the Altan Khanate, trying to unseat Sholui Ubashi Khong Tayiji from Dzungaria. The continuous, back-and-forth nature of the struggle, which generally defined this period, is captured in the Oirat epic song "The Rout of Mongolian Sholui Ubashi Khong Tayiji," recounting the Oirat victory over the First Khan of the Altan Khanate in 1587.

Resurgence of Oirat Power

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the First Altan Khan drove the Oirats westward to present-day eastern Kazakhstan. The Torghuts became the westernmost Oirat tribe, encamped in the Tarabagatai region and along the northern stretches of the Irtysh, Ishim and Tobol Rivers. Further west, the Kazakhs, a Turco-Mongol Muslim people, prevented the Torghuts from sending trading caravans to the Muslim towns and villages located along the Syr Darya river. As a result, the Torghuts established a trading relationship with the newly established outposts of the Tsarist government whose expansion into and exploration of Siberia was motivated primarily by the desire to profit from trade with Asia.

The Khoshuts, the easternmost Oirat tribe, encamped near the Lake Zaisan area and the Semipalatinsk region along the lower portions of the Irtysh river where they built several steppe monasteries. The Khoshuts were adjacent to the Eastern Mongol khanates of Altan Khan and Dzasagtu Khan. Both Khanates prevented the Khoshuts and the other Oirat tribes from trading with Chinese border towns. The Khoshuts were ruled by Baibagas Khan and Güshi Khan, the first of the Oirat leaders to convert to the Gelugpa sect.

Locked in between both tribes were the Choros, Dörbets and Khoits (collectively "Dzungars"), who were slowly rebuilding the base of power they had enjoyed under the Dörben Oirat. The Choros were the dominant Oirat tribe of that era. Their chieftain, Khara Khula attempted to follow Esen Khan in unifying the Oirat tribes to challenge the Eastern Mongols and their Manchu patrons for domination of Mongolia.

Under the dynamic leadership of Khara Khula, the Dzungars stopped the expansion of the First Altan Khan and began planning the resurrection of the Dörben Oirat under the Dzungar banner. In furtherance of such plans, Khara Khula designed and built a capital city called "Kubak-sari," on the Imil river near the modern city of Chuguchak. During his attempt to build a nation, Khara Khula encouraged diplomacy, commerce and farming. He also sought to acquire modern weaponry and build small industry, such as metal works, to supply his military.

The attempted unification of the Oirats gave rise to dissension among the tribes and their strongly independent Chief Tayishis. This dissension reputedly caused Kho Orluk to move the Torghut tribe and elements of the Dörbet tribe westward to the Volga region where his descendants formed the Kalmyk Khanate. In the east, Güshi Khan took part of the Khoshut tribe to the Tsaidam and Koko Nor regions in the Tibetan plateau where he formed the Khoshut Khanate to protect Tibet and the Gelugpa sect from both internal and external enemies. Khara Khula and his descendants formed the Dzungar Empire to fight the Eastern Mongols.

The Torghut Migration

In 1618, the Torghuts, led by their Tayishi, Kho Orluk, and a small contingent of Dörbets under Tayishi Dalai Batur migrated from the upper Irtysh river region to the grazing pastures of the lower Volga River region, located south of Saratov and north of the Caspian Sea, on both banks of the Volga River. Together they moved west through southern Siberia and the southern Urals, bypassing a more direct route that would have taken them through the heart of the territory of their enemy, the Kazakhs. Along the way they raided Russian settlements and Kazakh and Bashkir encampments.

Many theories have been advanced to explain the migration. One generally accepted theory is that the attempt by Khara Khula, Tayishi of the Dzungars, to centralize political and military control over the tribes under his leadership may have given rise to discontent among the Oirat tribes. Some scholars, however, believe that the Torghuts simply sought uncontested pastures because their territory was being increasingly encroached upon by the Russians from the north, the Kazakhs from the south and the Dzungars from the east, resulting in overcrowding and a severely diminished food supply. A third theory suggests that the Torghuts grew weary of the militant struggle between the Oirats and the Altan Khanate.

The Kalmyk Khanate

Period of Self Rule, 1630-1724

When they arrived in the lower Volga region in 1630, the Oirats encamped on land that had once been part of the Astrakhan Khanate, but was now claimed by the Tsarist government. The region was mostly uninhabited, from south of Saratov to the Russian garrison at Astrakhan and on both the east and the west banks of the Volga River. The Tsarist government was not ready to colonize the area and was in no position to prevent the Oirats from encamping in the region, but it had a direct political interest in insuring that the Oirats would not become allies with its Turkic-speaking neighbors.

The Oirats quickly consolidated their position by expelling the majority of the native inhabitants, the Nogai Horde. Large groups of Nogais fled eastward to the northern Caucasian plain and to the Crimean Khanate, territories then under Ottoman Turkish rule. Smaller groups of Nogais sought the protection of the Russian garrison at Astrakhan. The remaining nomadic tribes became vassals of the Oirats.

At first, an uneasy relationship existed between the Russians and the Oirats. Oirats raids on Russian settlements, and raids by Cossacks and Bashkirs (Muslim vassals of the Russians) on Oirat encampments, were commonplace. Numerous oaths and treaties were signed to ensure Oirat loyalty and military assistance. Although the Oirats became subjects of the Tsar, their allegiance was deemed to be nominal.

The Oirats governed themselves according to a document known as the Great Code of the Nomads (Iki Tsaadzhin Bichig), promulgated during a summit in 1640 by the Oirats, their brethren in Dzungaria and some of the Eastern Mongols who all gathered near the Tarbagatai Mountains in Dzungaria to resolve their differences and to unite under the banner of the Gelugpa sect. Although the goal of unification was not met, the summit leaders ratified the Code, which regulated all aspects of nomadic life.

In securing their position, the Oirats became a borderland power, often allying themselves with the Tsarist government against the neighboring Muslim population. During the era of Ayuka Khan, the Oirats rose to political and military prominence as the Tsarist government sought the increased use Oirat cavalry in support of its military campaigns against the Muslim powers in the south, such as Persia, the Ottoman Empire, the Nogays and the Kuban Tatars and Crimean Khanate. Ayuka Khan also waged wars against the Kazakhs, subjugated the Mangyshlak Turkmens, and made multiple expeditions against the highlanders of the North Caucasus. These campaigns highlighted the strategic importance of the Kalmyk Khanate as a buffer zone, separating Russia and the Muslim world, as Russia fought wars in Europe to establish itself as a European power.

The Tsarist government increasingly relied on the provision of monetary payments and dry goods to the Oirat Khan and the Oirat nobility to acquire the support of Oirat cavalrymen for its military campaigns. In that respect, the Tsarist government treated the Oirats as it did the Cossacks. The monetary payments did not stop the mutual raiding, and, in some instances, both sides failed to fulfill its promises[12].

Another significant incentive that the Tsarist government provided to the Oirats was tariff-free access to the markets of Russian border towns, where the Oirats were permitted to barter their herds and the items they obtained from Asia and their Muslim neighbors in exchange for Russian goods. Trade also occurred with neighboring Turkic tribes under Russian control, such as the Tatars and the Bashkirs, and intermarriage became common. These trading arrangements provided substantial benefits, monetary and otherwise, to the Oirat tayishis, noyons and zaisangs.

Historian Fred Adelman describes this era as the Frontier Period, lasting from the advent of the Torghut under Kho Orluk in 1630 to the end of the great khanate of Kho Orluk’s descendant, Ayuka Khan, in 1724, a phase accompanied by little discernible acculturative change[13].

During the era of Ayuka Khan, the Kalmyk Khanate reached the peak of its military and political power. The Khanate experienced economic prosperity from free trade with Russian border towns, China, Tibet and with their Muslim neighbors. During this era, Ayuka Khan also kept close contacts with his Oirat kinsmen in Dzungaria, as well as the Dalai Lama in Tibet.

From Oirat to Kalmyk

Sometime after arriving near the Volga River, the Oirats began to identify themselves as "Kalmyk." This named was supposedly given to them by their Muslim neighbors and later used by the Russians to describe them. The Oirats used this name in their dealings with outsiders such as their Russian and Muslim neighbors, but continued to refer to themselves by their tribal, clan, or other internal affiliations.

The name Kalmyk wasn't immediately accepted by all of the Oirat tribes in the lower Volga region. As late as 1761, the Khoshut and Dzungars (refugees from the Manchu Empire) referred to themselves and the Torghuts exclusively as Oirats. The Torghuts, by contrast, used the name Kalmyk for themselves as well as the Khoshut and Dzungars.[14] Over time, the descendants of the Oirat migrants in the lower Volga region embraced the name Kalmyk, irrespective of their location in Astrakhan, the Don Cossack region, Orenburg, Stavropol, the Terek and the Urals. Another generally accepted name is Ulan Zalata or the "red buttoned ones."[15].

Generally, European scholars have identified all West Mongolians collectively as Kalmyks, regardless of their location. Such scholars (including Sebastian Muenster) relied on Muslim sources that traditionally used the word Kalmyk as a derogatory term for the West Mongolians. The West Mongolians of China and Mongolia have continued to regard the name “Kalmyk” as derogatory[16] and instead refer to themselves as Oirat or they go by their respective tribal names, such as Khoshut, Dörbet, Choros, Torghut, Khoit, Bayid, Mingat[17].

Reduction in Autonomy, 1724-1771

After the death of Ayuka Khan in 1724, the political situation among the Kalmyks became unstable as various factions sought to be recognized as Khan. The Tsarist government gradually chipped away at the autonomy of the Kalmyk Khanate by encouraging the establishment of Russian and German settlements. The Tsarist government imposed a council on the Kalmyk Khan, weakening his authority, while continuing to expect the Kalmyk Khan to provide cavalry units to fight on behalf of Russia. The Russian Orthodox Church pressured many Kalmyks to adopt Orthodoxy. By the mid-eighteenth century, Kalmyks were increasingly disillusioned with settler encroachment and interference in their internal affairs.

In the winter of 1770-1771, Ubashi Khan, the great-grandson Ayuka Khan and the last Kalmyk Khan, decided to return his people to their ancestral homeland, Dzungaria, then firmly under control of the Manchu Empire. The Dalai Lama was asked to give his blessing and to set the date of departure. After consulting the astrological chart, the Dalai Lama set the date for their return, but at the moment of departure, the thinning of the ice on the Volga River permitted only those Kalmyks who roamed on the left or eastern bank to leave. Those on the right bank were forced to stay behind.

Under Ubashi Khan’s leadership, approximately 200,000 Kalmyks, five-sixths of the Torghut tribe, began the journey from their pastures on the left bank of the Volga River to Dzungaria. Most of the Khoshuts, Choros and Khoits also accompanied the Torghuts on their journey to Dzungaria. The Dörbet tribe elected not to go.

Ubashi Khan chose the quickest route, which took them directly across the Central Asian desert, through the territories of their Kazakh and Kyrgyz enemies. Many Kalmyks were killed in ambushes or captured and enslaved along the way. Some groups became lost, and some returned to Russia. Most of the Kalmyk livestock either perished or was seized. Consequently, many people died of starvation or of thirst. After several grueling months of travel, only one-third of the original group reached Dzungaria where the officials and troops of the Manchu Empire awaited them.

After failing to stop their flight, Catherine the Great dissolved the Kalmyk Khanate, transferring all governmental powers to the Governor of Astrakhan. The title of Khan was abolished. The highest native governing office remaining was that of the Vice-Khan, who also was recognized by the government as the highest ranking Kalmyk prince. By claiming the authority to appoint the Vice-Khan, the Tsarist government was now entrenched as the decisive force in Kalmyk government and affairs.

Life in Tsarist Russia

After the 1771 exodus, the Kalmyks that remained part of the Russian Empire were firmly under the control of the Tsarist government. They continued their nomadic pastoral lifestyle, ranging the pastures between the Don and the Volga Rivers, and wintering in the lowlands along the shores of the Caspian Sea as far as Lake Sarpa to the northwest and Lake Manych to the west. In the spring, they moved along the Don River and the Sarpa lake system, attaining the higher grounds along the Don in the summer, passing the autumn in the Sarpa and Volga lowlands. In October and November they returned to their winter camps and pastures[18].

Despite their greatly reduced numbers, the Torghuts still remained the dominant Kalmyk tribe. The other Kalmyk tribes in Russia included Dörbets and Khoshuts. Elements of the Choros and Khoits tribes also were present in numbers too small to retain their ulus (tribal divisions) as independent administrative units, and were absorbed by the ulus of the larger tribes.

The factors that caused the 1771 exodus continued to trouble the remaining Kalmyks. In the wake of the exodus, the Torghuts joined the Cossack rebellion of Yemelyan Pugachev in hopes that he would restore the independence of the Kalmyks. After the Pugachev rebellion was defeated, Catherine the Great transferred the office of the Vice-Khan from the Torghut tribe to the Dörbet tribe, whose princes had supposedly remained loyal to the government during the rebellion. The Torghuts were thus removed from their role as the hereditary leaders of the Kalmyk people. The Khoshuts could not challenge this political arrangement due to the smaller size of their population.

The disruptions to Kalmyk society caused by the exodus and the Torghut participation in the Pugachev rebellion precipitated a major realignment in Kalmyk tribal structure. The government divided the Kalmyks into three administrative units attached, according to their respective locations, to the district governments of Astrakhan, Stavropol and the Don and appointed a special Russian official bearing the title of "Guardian of the Kalmyk People" for purposes of administration. The government also resettled some small groups of Kalmyks along the Ural, Terek and Kuma rivers and in Siberia.

The redistricting divided the now dominant Dörbet tribe into three separate administrative units. Those in the western Kalmyk steppe were attached to the Astrakhan district government. They were called Baga (Lessor) Dörbet. The Dörbets who moved to the northern part of the Stavropol province were called Ike (Greater) Dörbet even though their population was smaller. The Kalmyks of the Don became known as Buzava. Although they were composed of elements of all the Kalmyk tribes, the Buzava claimed descent primarily from the Dörbet tribe. Their name is derived from two tributaries of the Don River: Busgai and Busuluk. In 1798, Tsar Paul I recognized the Don Kalmyks as Don Cossacks. As such, they received the same rights and benefits as their Russian counterparts in exchange for providing national military services.

Over time, the Kalmyks gradually created fixed settlements with houses and temples, in place of transportable round felt yurts. In 1865, Elista, the future capital of the Kalmyk Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was founded. This process lasted until well after the Russian Revolution.

Russian Revolution and Civil War

Like most people in Russia, the Kalmyks greeted the February 1917 revolution with enthusiasm. Kalmyk leaders believed that the Russian Provisional Government, which replaced the Tsarist government, would allow them greater autonomy and religious, cultural and economic freedom. This enthusiasm soon disappeared when the Bolsheviks took control over the national government during the second revolution in November 1917.

After the Bolsheviks took control, various political and ethnic groups opposed to Communism organized a loose political and military coalition called the "White Movement." A volunteer army (called the "White Army") was raised to fight the Red Army, the military arm of the Bolshevik government. Initially, this army was composed primarily of volunteers and Tsarist supporters, but it was later joined by the Cossacks (including Don Kalmyks), many of whom resisted the Bolshevik policy of de-Cossackization.

The second revolution split the Kalmyk people into opposing camps. Many were dissatisfied with the Tsarist government for its historic role in promoting the colonization of the Kalmyk steppe and in undermining the autonomy of the Kalmyk people. Others felt hostility towards Bolshevism for two reasons: their loyalty to their traditional leaders (anti-Communist nobility and clergy) was deeply ingrained; and the Bolsheviks had exploited the conflict between the Kalmyks and the local Russian peasants who seized Kalmyk land and livestock [19].

The Astrakhan Kalmyk nobility, led by Prince Dmitri Tundutov of the Baga Dörbets and Prince Sereb-Djab Tiumen of the Khoshuts, expressed their anti-Bolshevik sentiments by seeking to integrate the Astrakhan Kalmyks into the military units of the Astrakhan Cossacks. Before a general mobilization of Kalmyk horsemen could occur, the Red Army seized power in Astrakhan.

After the capture of Astrakhan, the Bolsheviks engaged in savage reprisals against the Kalmyk people, especially against Buddhist temples and the Buddhist clergy [20]. Eventually the Bolsheviks drafted as many as 18,000 Kalmyk horsemen into the Red Army to prevent them from joining the White Army [21], but many of those Kalmyk horsemen defected to the White side.

The majority of the Don Kalmyks sided with the White Movement to preserve their Cossack lifestyle and proud traditions. As Don Cossacks, the Don Kalmyks first fought under White army General Anton Denikin and then under his successor, General Pyotr Wrangel. Because the Don Cossack Host to which they belonged was the main center of the White Movement and of Cossack resistance, disastrous battles were fought primarily on Cossack lands. Villages and entire regions changed hands repeatedly in a fratricidal conflict in which both sides committed terrible atrocities. The Don Cossacks, including the Don Kalmyks, experienced particularly heavy military and civilian losses, both from the fighting itself and from starvation and disease induced by the war. One historian contends that the Bolsheviks were guilty of the mass extermination of the Don Cossack people, killing an estimated 70 percent (or 700,000 persons) of the Don Cossack population[22].

In October, 1920, the Red Army smashed General Wrangel's resistance in the Crimea, forcing the evacuation of some 150,000 White army soldiers and their families to Constantinople, Turkey. A small group of Don Kalmyks managed to escape on the British and French vessels that came to rescue the White army. This group resettled in Europe, primarily in Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia and France, where its leaders remained active in the White movement. In 1922, several hundred Don Kalmyks returned home under a general amnesty. Some returnees, including Prince Dmitri Tundutov, were imprisoned and then executed soon after their return.

Formation of the Kalmyk Soviet Republic

The Soviet government established the Kalmyk Autonomous Oblast in November 1920 by merging the Stavropol Kalmyk settlements with a majority of the Astrakhan Kalmyks. A small number of Don Kalmyks (Buzava) from the Don Host migrated to this Oblast. The administrative center was Elista, a small village in the western part of the Oblast that was expanded in the 1920s to reflect its status as the capital of the Oblast.

In October 1935, the Kalmyk Autonomous Oblast was reorganized into the Kalmyk Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. The chief occupations of the Republic were cattle breeding, agriculture, including the growing of cotton and fishing. There was no industry.

Collectivization

In 1929, Joseph Stalin ordered the forced collectivization of agriculture, forcing the Astrakhan Kalmyks to abandon their traditional nomadic pastoralist lifestyle and to settle in villages. All Kalmyk herdsmen owning more than 500 sheep were deported to labor camps in Siberia. Kalmyk resistance to Stalin’s collectivization campaign and the famine that was induced by such campaign resulted in the deaths of a substantial number of Kalmyks.

In the 1930s, Stalin ordered the closure of all Buddhist monasteries and libraries, burning temples and religious texts in the process. The Buddhist clergy was either shot or condemned to long terms of confinement in the labor camps in Siberia where they all perished.

World War II and exile

In June 1941 the German army invaded the Soviet Union, taking control of the Kalmyk Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. In December 1942, however, the Red Army liberated the Republic from German control. On 28th of December 1943, the Soviet government accused the Kalmyks of collaborating with the Germans and deported the entire population, including Kalmyk Red Army soldiers, to various locations in Central Asia and Siberia. The deportation took place in 24 hours without notice, at night during the winter in unheated cattle cars. Between one-third and one-half of the Kalmyk population perished in transit from exposure or during the following years of exile from starvation and exposure. Deprived of any rights, the Kalmyk community ceased to exist, completing the ethnic cleansing of the Kalmyk people.

The Kalmyk Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was quickly dissolved. Its territory was divided and transferred to the adjacent regions, the Astrakhan and Stalingrad Oblasts and Stavropol Krai. To completely obliterate any traces of the Kalmyk people, the Soviet authorities changed the names of towns and villages from Kalmyk names to Russian names. For example, Elista became Stepnoi.

Return from Siberian exile

In 1957, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev permitted the Kalmyk people to return to their homes. Upon return, the Kalmyks found their homeland had been settled by Russians and Ukrainians, many of whom chose to remain. On January 9, 1957, Kalmykia once again became an autonomous oblast, and on July 29, 1958, an autonomous republic within the Russian SFSR.

In the following years, poor planning of agricultural and irrigation projects resulted in widespread desertification. Industrial plants were constructed without any analysis of the economic viability of such plants.

In 1992, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Kalmykia chose to remain an autonomous republic of the successor government, the Russian Federation. The dissolution, however, facilitated the collapse of the economy at both the national and the local level, causing widespread economic and social hardship. The resulting upheaval caused many young Kalmyks to leave Kalmykia, especially in the rural areas, for economic opportunities in and outside the Russian Federation.

Treatment as non-Mongols

Historically, the Eastern Mongols (the Khalkha, Chahar and Tümed tribes) have regarded the Oirats as non-Mongols. Since their lineage was traceable directly to the Mongolian Yuan Dynasty and its progenitor, Genghis Khan, they claimed exclusive rights to the name "Mongols," the title "Khan," and the historic legacy attached to that name and title. The Oirats, although not considered direct descendants of Genghis Khan, are associated with Genghis Khan's brother, Khasar, who was in command of the Khoshut tribe.

In response to the Western Mongol's self-designation as the "Dörben Oirat," the Eastern Mongols distinguished themselves as the "Döchin Mongols" (Forty Mongols). They also used the designation "Döchin Dörben Khoyar" (The Forty and the Four), representing their claim that the Eastern Mongols had 40 tümen (a cavalry unit comprised of 10,000 horseman) to the four tümen maintained by the Dörben Oirat.[23]. Ironically, by the early 1690s, the Dzungar (successor state to the Dörben Oirat) attacks against the Eastern Mongols were so persistent and ferocious that the Eastern Mongol princes voluntarily led their people and Outer Mongolia into submission to the Manchu state.

Until recently, the Oirats (including the Kalmyks) have not recognized themselves as Mongols or even as Western Mongols. Nevertheless, there is evidence of a close relationship among all Mongolian-speaking peoples, principally the Kalmyks, Oirats, Khalkhas and Buriats. They share similar physical characteristics with the Mongol people, have a close linguistic affinity, adhere to Tibetan Buddhism, and maintain similar customs and traditions, despite centuries of internecine warfare and extensive and far-reaching migrations[24]. They also share similar sub-tribal names such as Kereit, Taichiut, Merkit and Chonos.

A recent genetic study of the Kalmyks seems to support their Mongol origins. The Kalmyks, unlike other Eurasian peoples from the steppes of Siberia, have not substantially mixed with Russian and other Eastern European peoples[25], suggesting that entire families of Kalmyks migrated to the Volga region, rather than only males, as is common with most nomadic tribal groups.

Religion

The Kalmyks are the only inhabitants of Europe whose national religion is Buddhism. They embraced Buddhism in the early part of the seventeenth century and belong to the Tibetan Buddhist sect known as the Gelugpa (Virtuous Way), commonly referred to as the Yellow Hat sect. The religion is derived from the Indian Mahayana form of Buddhism. In the West, it is commonly referred to as Lamaism, from the name of the Tibetan monks, the lamas ("heavy with wisdom").[26] Prior to their conversion, the Kalmyks practiced shamanism.

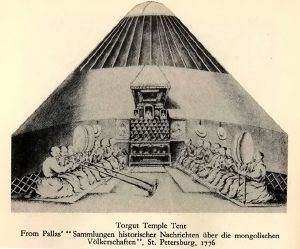

Historically, Kalmyk clergy received their training either on the steppe or in Tibet. The pupils who received their religious training on the steppe joined Kalmyk monasteries, which were active centers of learning. Many of these monasteries operated out of felt tents, which accompanied the Kalmyk tribes as they migrated. The Oirats maintained tent monasteries throughout present-day eastern Kazakhstan and along the migratory route they took across southern Siberia to the Volga. They also maintained tent monasteries around Lake Issyk Kul in present-day Kyrgyzstan.

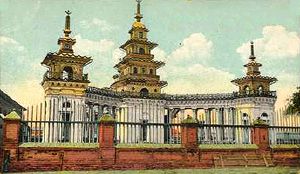

The Oirats also built stone monasteries in the regions of eastern Kazakhstan. The remains of stone Buddhist monasteries have been found at Almalik and at Kyzyl-Kent (See image to the right). In addition, there was a great Buddhist monastery in Semipalatinsk (seven palaces), which derives its name from that seven-halled Buddhist temple. Further, remains of Buddhist monasteries have been found at Ablaiket near Ust Kamenogorsk and at Talgar, near Almaty, and at Sumbe in the Narynkol region, bordering China.[27]

After completing their training, Kalmyk clergy dispensed not only spiritual guidance but as medical advice. Kalmyk lamas enjoyed heightened political status among the nobility and held a strong influence over the general tribal population. The Kalmyk monastic system offered commoners a path to literacy and prestige.

Religious persecution

The policy of the Russian Tsarist government and the Russian Orthodox Church was to gradually absorb and convert any subject of another creed or nationality, as a means of eliminating foreign influence and firmly entrenching newly annexed areas. Once baptized, the indigenous population would become loyal to the Russian Empire and would agree to be governed by Russian officials.

The Kalmyks migrated to territory along the Volga River which later was annexed by the Tsarist government, and became subject to this policy. At first, the policies contributed to the conversion of the Kalmyk nobility. Among the earliest converts were the children of Donduk-Ombo, the sixth Khan of the Kalmyks (reigned 1737 – 1741), and his Circassian-born wife. After the death of Donduk-Ombo, his throne was usurped by a cousin and his widow converted to Russian Orthodoxy and sought the protection of Empress Elizabeth. In 1745 her children were baptized and authorized to bear the name of Princes Dondukov. Her eldest son, Prince Aleksey Dondukov, was sent by Catherine the Great to govern Kalmykia and reigned as a puppet khan from 1762 until his death 19 years later. Another important convert was Baksaday-Dorji, the grandson of Ayuka Khan, who adopted the Christian name, Peter Taishin. Each of these conversions was motivated by political ambition to become the Kalmyk Khan. Kalmyk Tayishis were given salaries and towns and settlements were established for them and their ulus (tribal divisions)[28].

When the Tsarist government began encouraging Russian and German settlements along the Volga, they took the most fertile land and left the barren areas as grazing lands for the Kalmyk herds. The resulting reduction in the size of their herds impoverished the Kalmyk Tayishis, some of whom led their ulus to Christianity to obtain economic benefits.

To discourage the monastic lifestyle, the Tsarist government mandated the building of permanent structures at government-designated sites by Russian architects [29]. Lamaist canonical regulations governing monastery construction were suspended and Kalmyk temples were constructed to resemble Russian Orthodox churches. The Khoshutovsky Khurul is modeled after the Kazan Cathedral in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

The Tsarist government implemented policies to gradually weaken the influence of the lamas, severely restricting Kalmyk contact with Tibet and giving the Tsar authority to appoint the Šajin Lama (High Lama of the Kalmyks). The economic crises resulting from encroachment of Russian and German settlers forced many monasteries and temples to close and lamas to adopt a secularized lifestyle. The effects of these policies are evident in the decrease in the number of Kalmyk monasteries in the Volga region during the nineteenth century[30]

Table – Number of Kalmyk Monasteries in the Volga Region Year Number early 19th century 200 1834 76 1847 67 before 1895 62 before 1923 60+

Like the Tsarist government, the Communist regime was aware of the influence the Kalmyk clergy held over the general population. In the 1920s and the 1930s, the Soviet government implemented policies to eliminate religion through control and suppression. Kalmyk khuruls (temples) and monasteries were destroyed and property confiscated; the clergy and many believers were harassed, killed, or sent to labor camps; religious artifacts and books were destroyed; and young men were prohibited from religious training.

By 1940 all Kalmyk Buddhist temples were either closed or destroyed and the clergy systematically oppressed. Dr. Loewenthal writes that these policies were so harshly enforced that the Kalmyk clergy and Buddhism were not even mentioned in the work by B. Dzhimbinov, "Sovetskaia Kalmykiia," (Soviet Kalmyks) published in 1940. In 1944, the Soviet government exiled all Kalmyks not fighting in the Soviet army to Central Asia and Siberia, accusing them of collaborating with the German Army. Upon rehabilitation in 1957, the Kalmyks were permitted to return home from exile, but all their attempts to restore their religion and to build a temple failed.

By the 1980s, the Soviet campaign against religion had been so thorough that a majority of the Kalmyks had never received any formal spiritual guidance. In the late 1980s, however, the Soviet government changed its course and implemented policies favoring liberalization of religion. The first Buddhist community was organized in 1988. By 1995, there were 21 Buddhist temples, 17 places of worship for various Christian denominations, and 1 mosque in the Republic of Kalmykia[31].

On December 27, 2005 a new khurul (temple) "Burkhan Bakshin Altan Sume," opened in Elista, the capital of the Republic of Kalmykia. It is the largest Buddhist temple in Europe. The government of the Republic of Kalmykia sought to build a magnificent temple on a monumental scale in hopes of creating an international learning center for Buddhist scholars and students from all over the world. More significantly, the temple is a monument to the Kalmyk people who died in exile between 1944 and 1957.[32]

Notes

- ↑ Michael Khodarkovsky. Where Two Worlds Met: The Russian State and the Kalmyk Nomads 1600-1771. (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1992), 5 citing Bretschneider, 1910:2:167

- ↑ René Grousset. The Empire of the Steppes: a History of Central Asia. (Rutgers University Press, 1970), 506

- ↑ BBC News Regions and territories: Kalmykia Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ↑ Ethnologue.com Kalmyk-Oirat A language of Russia (Europe) Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ↑ Nicholas N. Poppe. The Mongolian Language Handbook. (Center for Applied Linguistics, 1970)

- ↑ Arash Bormanshinov. The Kalmyks: Their Ethnic, Historical, Religious, and Cultural Background. (Kalmyk American Cultural Association, Occasional Papers Number One, 1990.)

- ↑ Anonymous. Donskaia Oblast, Donskoi Pervyi Okrug, Donskoi Vtoroi Okrug (translation: The Don Region, First Don District, Second Don District), (Novyi Entsliklopedicheskii Solvar, XVI, 1914), 653-660

- ↑ Paul Pelliot. Notes sur le Turkestan. (Brill: T'oung Pao, XXVII, 1930), 30

- ↑ Republic of Kalmykia, History of Kalmykia Retrieved August 19, 2008. (in English)

- ↑ Grousset, 502-541

- ↑ Grousset, 1970, 510

- ↑ Stephen A. Halkovic, Jr., THE MONGOLS OF THE WEST. Indiana University Uralic and Altaic Series, Volume 148, Larry Moses, Ed. (Bloomington: Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies, Indiana University, 1985), 41-54

- ↑ Fred Adelman. Kalmyk Cultural Renewal. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 1960, 14-15)

- ↑ Khodarkovsky, 8

- ↑ Adelman, 1960, 6

- ↑ Henning Haslund. MEN AND GODS IN MONGOLIA. (National Travel Club, New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1935), 214-215

- ↑ D. Anuchin, "Kalmyki," Entsiklopedicheskii Slovar Brokgauz-Efrona, XIV, (Saint Petersburg: 1914), 57 (in Russian)

- ↑ Lawrence Krader. Social Organization of the Mongol-Turkic Pastoral Nomads. (Indiana University Publications, Uralic and Altaic Series, Vol. 20., 1963), 121, citing Pallas, vol. 1, 1776, 122-123

- ↑ Rudolf Loewenthal. THE KALMUKS AND OF THE KALMUK ASSR: A Case in the Treatment of Minorities in the Soviet Union. (External Research Paper No. 101, Office of Intelligence Research, Department of State, September 5, 1952).

- ↑ Dorzha Arbakov. Genocide in the USSR, Chapter II, Complete Destruction of National Groups as Groups, The Kalmyks, Nikolai Dekker and Andrei Lebed, (Eds.), (Munich: Series I, No. 40, Institute for the Study of the USSR, 1958), 30-36

- ↑ T.K Borisov. Kalmykiya; a historic-political and socio-economic survey. (Moscow-Leningrad: 1926), 84

- ↑ Mikhail Heller and Aleksandr M. Nekrich. Utopia in Power: The History of the Soviet Union from 1917 to the Present. (Summit Books, 1988), 87

- ↑ Khodarkovsky, 1992, 7

- ↑ Arash Bormanshinov. The Kalmyks: Their Ethnic, Historical, Religious, and Cultural Background. Kalmyk American Cultural Association, Occasional Papers Number One, 1990:3

- ↑ Ivan Nasidze, Dominique Quinque, Isabelle Dupanloup, Richard Cordaux, and Lyudmila Kokshunova, and Mark Stoneking, Genetic Evidence for the Mongolian Ancestry of Kalmyks AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 126 (2005) Retrieved August 19, 2008

- ↑ Bartleby.com Tibetan Buddhism The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001-07. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ↑ Alexander Berzin (September 1994, revised November 2006) (Archeological information provided by Sergei Sokolov) Historical Sketch of Buddhism and Islam in West Turkistan. The Berzin Archives. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ↑ Khodarkovsky, 39

- ↑ A.M. Pozdneev, "Kalmytskoe Verouchenie," Entsiklopedicheskii Slovar Brokgauz-Efrona, XIV, (Saint Petersburg, 1914).

- ↑ Rudolf Loewenthal. THE KALMUKS AND OF THE KALMUK ASSR: A Case in the Treatment of Minorities in the Soviet Union. (External Research Paper No. 101, Office of Intelligence Research, Department of State), (September 5, 1952), citing Riasanovsky, 1929

- ↑ François Grin. Kalmykia: From Oblivion to Assertion. (European Center or Minority Issues, ECMI Working Paper #10, 2000), 7

- ↑ Europe's biggest Buddhist temple opens in Kalmykia REGNUM, Dec 27, 2005. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adelman, Fred. Kalmyk Cultural Renewal. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 1960, 14-15

- Anonymous. Donskaia Oblast, Donskoi Pervyi Okrug, Donskoi Vtoroi Okrug (translation: The Don Region, First Don District, Second Don District), Novyi Entsliklopedicheskii Solvar, XVI, 1914, 653-660.

- Anuchin, D. "Kalmyki," Entsiklopedicheskii Slovar Brokgauz-Efrona, XIV, St. Petersburg, 1914, 57.

- Arbakov, Dorzha. Genocide in the USSR. Chapter II, Complete Destruction of National Groups as Groups, The Kalmyks, Nikolai Dekker and Andrei Lebed, Editors, Series I, No. 40: 30-36, Munich: Institute for the Study of the USSR, 1958. *Borisov, T.K. Kalmykiya; a historic-political and socio-economic survey, Moscow-Leningrad, 1926:84.

- Berzin, Alexander, (September 1994, revised November 2006) (Archeological information provided by Sergei Sokolov) Historical Sketch of Buddhism and Islam in West Turkistan. The Berzin Archives. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- Borisov, T.K. Kalmykiya; a historic-political and socio-economic survey. Moscow-Leningrad: 1926, 84.

- Bormanshinov, A. Lamas of the kalmyk people: the don kalmyk lamas. Bloomington: Inst For Inner-Asian Studies, 1991.

- Bormanshinov, Arash. The Kalmyks, Their Ethnic, Historical, Religious, and Cultural Background. Publications of the Kalmyk American Cultural Association, no. 1. Howell, NJ: Kalmyk American Cultural Association, 1990.

- Bormanshinov, Arash. The Kalmyks: Their Ethnic, Historical, Religious, and Cultural Background. Kalmyk American Cultural Association, Occasional Papers Number One, 1990.

- Geller, Mikhail, and A. M. Nekrich. Utopia in Power: The History of the Soviet Union from 1917 to the Present. New York: Summit Books, 1986.

- Grin, François. Kalmykia: From Oblivion to Assertion, European Center or Minority Issues. ECMI Working Paper #10, 2000, 7.

- Grousset, René. The Empire of the Steppes; A History of Central Asia. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1970.

- Guchinova, Ė.-B. 2006. The Kalmyks. (Caucasus world) London: Routledge. ISBN 0700706577 ISBN 9780700706570.

- Halkovic, Jr., Stephen A. THE MONGOLS OF THE WEST. Indiana University Uralic and Altaic Series, Volume 148, Larry Moses, Editor, Bloomington: Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies, Indiana University, 1985. 41-54.

- Haslund-Christensen, Henning, Elizabeth Sprigge, and Claude Napier. Men and Gods in Mongolia (Zayagan). New York: E.P. Dutton & Co, 1935.

- Heller, Mikhail and Aleksandr M. Nekrich. Utopia in Power: The History of the Soviet Union from 1917 to the Present. Summit Books, 1988.

- Kaarsberg, Hans S. 1996. Among the kalmyks of the steppes on horseback and by troika: a journey made in 1890. Bloomington: Mongolia Soc. ISBN 0910980594.

- Khodarkovsky, Michael, and Azade-Ayse Rorlich. 1995. "Where Two Worlds Met: The Russian State and the Kalmyk Nomads, 1600-1771." The American Historical Review 100 (5): 1630.

- Khodarkovsky, Michael. 1992. Where two worlds met: the Russian state and the Kalmyk nomads, 1600-1771. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801425557.

- Krader, Lawrence. Social Organization of the Mongol-Turkic Pastoral Nomads, Indiana University Publications, Uralic and Altaic Series 20 (1963): 121, citing Pallas, vol. 1, 1776: 122-123.

- Loewenthal, Rudolf. THE KALMUKS AND OF THE KALMUK ASSR: A Case in the Treatment of Minorities in the Soviet Union. External Research Paper No. 101, Office of Intelligence Research, Department of State, September 5, 1952.

- Pelliot, Paul. Notes sur le Turkestan. Brill: T'oung Pao, XXVII, 1930.

- Poppe, Nicholas N. The Mongolian Language Handbook. Center for Applied Linguistics, 1970.

- Ramstedt, G. J., and John Richard Krueger. 1978. Seven journeys eastward, 1898-1912: among the Cheremis, Kalmyks, Mongols, and in Turkestan, and to Afghanistan. Bloomington, IN: Mongolia Society. ISBN 0910980195.

- Riasanovsky, V.A. Customary Law of the Mongol Tribes (Mongols, Buriats, Kalmucks). Harbin: 1929.

- Richardson C., "Stalinist terror and the Kalmyks' national revival: a cultural and historical perspective." Journal of Genocide Research 4 (3) (September 2002): 441-451.

- The Kalmycks. 1976. Willingboro, NJ: D.N. Bajanowa.

- Williamson, H.N.H. FAREWELL TO THE DON: The Russian Revolution in the Journals of Brigadier H.N.H. Williamson, John Harris, Ed., New York: The John Day Company, 1970.

External links

All links retrieved October 4, 2022.

- The Construction of a Yurt

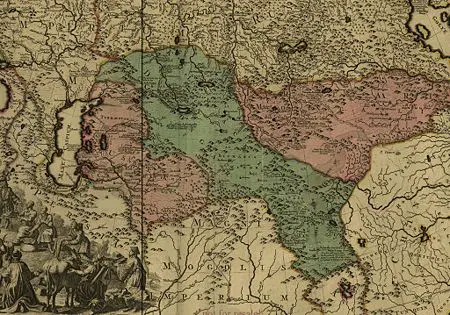

- "Carte de Tartarie," by Guillaume de L'Isle (1675-1726). From the Map Collection of the Library of Congress

- Kalmyk American Society.

- BBC News Regions and Territories: Kalmykia

- Historical Sketch of Buddhism and Islam in West Turkistan .berzinarchives.

- Europe's biggest Buddhist temple opens in Kalmykia.buddhistchannel.tv.

- Kalmyk Buddhist Temple in Belgrade, Yugoslavia (1929-1944);

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.