Kiang

| Kiang | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| Equus kiang Moorcroft, 1841 |

Kiang is the common name for a wild member of the horse family Equidae, Equus kiang, the largest of the wild asses, characterized by distinctive patches of white on the neck, chest, and shoulder, as well as long-legs and an erect mane. This odd-toed ungulate is native to the Tibetan Plateau, where it inhabits high-altitude montane and alpine grasslands, commonly from 2,700 to 5,400 meters elevation. Other common names for this species include Tibetan wild ass, khyang, and gorkhar.

While the kiang is hunted in some areas for meat, these large herbivores, that sometimes form temporary large herds, also provide value in attracting tourists. Ecologically, they also provide value as food for large predators, notably wolves. Thus, the kiang provides a larger function for the ecosystem and for humans while also advancing its own individual functions of survival and reproduction as a species.

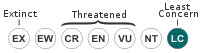

Kiangs remain in healthy number as a species and are classified as Lower Risk/Least Concern, although commercial hunting, loss of habitat, and conflicts with livestock provide threats to various populations. They have been decimated in the past and are missing from parts of their former range.

Overview and description

The kiang (Equus kiang) is a member of the Equidae, a family of odd-toed ungulate mammals of horses and horse-like animals. There are three basic groups recognized in Equidae—horses, asses, and zebras—although all extant equids are in the same genus of Equus. The kiang is one of three or four extant species of asses, which are placed together in the subgenus Asinus. The other species known as asses are the African wild ass (E. africanus, sometimes E. asinus), donkey or ass (E. asinus), and Asiatic wild ass or onager (E. hemionus). The kiang is related to the Asiatic wild ass (E. hemionus) and in some classifications it is a subspecies of this species, listed as E. hemionus kiang.

The kiang is the largest of the wild asses, with shoulder height of 100 to 142 centimeters (39-56 inches) (Grzimek et al. 2004). It has a large head, with a blunt muzzle and a convex nose. The mane is upright and relatively short.

A broad, dark chocolate-colored dorsal stripe extends from the dark-colored mane to the end of the tail, which ends in a tuft of blackish brown hairs. The coat is a rich chestnut color, darker brown in winter and a sleek reddish brown in late summer, molting its woolly fur. The summer coat is 1.5 centimeters long and the winter coat is double the length. The legs, undersides, and ventral part of the nape, end of the muzzle, and the inside of the pinnae are all white. Kiang have very slight sexual dimorphism.

Ekai Kawaguchi, a Japanese monk who traveled in Tibet from July, 1900 to June 1902, described the kiang in this manner (Kawaguchi 1909):

"As I have already said, khyang is the name given by the Tibetans to the wild horse of their northern steppes. More accurately it is a species of ass, quite as large in size as a large Japanese horse. In color it is reddish brown, with black hair on the ridge of the back and black mane and with the belly white. To all appearance it is an ordinary horse, except for its tufted tail. It is a powerful animal, and it is extraordinarily fleet."

Thubten Jigme Norbu, the elder brother of Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, reporting on his trip from Kumbum Monastery in Amdo to Lhasa in 1950, provided the following description (Norbu and Harrer 1986):

"I was struck by the noble appearance of these beasts; and, in particular, by the beautiful line of head and neck. Their coat is light brown on the back and whitish below the belly, and their long thin tails are almost black; the whole representing excellent camouflage against their natural background. They look wonderfully elegant and graceful when you see them darting across the steppes like arrows, heads stretched out and tails streaming away behind them in the wind."

Distribution and habitat

The kiang's distribution is centered on the Tibetan Plateau between 2700 meters (8,860-17,700 feet) above sea level. Ninety percent of the population is in China (mainly Tibet), but it also extends into northern parts of Nepal, Pakistan, and India. Although there are not reported sightings in Bhutan, it is possible the kiang's range extends into the extreme north and northwest of the country. The global population is estimated at 60,000 to 70,000 animals, with a Chinese population estimated at about 56,500 to 68,500 animals, of which the largest populations are in Tibet (Shah et al. 2008).

The kiang tends to live in open terrain, particularly alpine grasslands and arid steppes (Grzimek et al. 2004; Shah et al. 2008).

Behavior, diet, and ecology

As an equid, the African wild ass is a herbivore that feeds primarily on coarse, abundant, fibrous food. In particular, the diet of the kiang feeds on grasses and sedges, and especially Stipa spp., which are common grasses on the Tibetan Plateau. Sedges are occasionally eaten (Shah et al. 2008).

The social organization of kiangs appears to be similar to other wild equids in arid habitats, such as the Asiatic wild ass (E. hemionus) and the African wild ass (E. africanus), whereby there are no permanent groups other than the mother-foal groups. Temporary groups do form. Males tend to be solitary and territorial, and young males tend to form bachelor groups. Gestation is about 12 months (Shah et al. 2008; Grzimek et al. 2004).

The only real predator other than humans is the wolf. Kiangs defend themselves by forming a circle and, with heads down kick out violently. As a result wolves usually attack single animals who have strayed from the group (Norbu and Harrer 1986).

Kawaguchi (1909) described the behavior of the kiang from his travels in Tibet from 1900 to 1902:

"It is never seen singly, but always in twos or threes, if not in a herd of sixty or seventy. Its scientific name is Equus hemionis, but is for the most part called by its Tibetan name, which is usually spelled khyang in English. It has a curious habit of turning round and round, when it comes within seeing distance of a man. Even a mile and a quarter away, it will commence this turning round at every short stage of its approach, and after each turn it will stop for a while, to look at the man over its own back, like a fox. Ultimately it comes up quite close. When quite near it will look scared, and at the slightest thing will wheel round and dash away, but only to stop and look back. When one thinks it has run far away, it will be found that it has circled back quite near, to take, as it were, a silent survey of the stranger from behind. Altogether it is an animal of very queer habits."

Norbu and Harrer (1986), reporting on a trip of Norbu in 1950, observed the following behavior:

"Their rutting season is in the autumn, and then the stallions are at their most aggressive as they jealously guard their harems. The fiercest and most merciless battles take place at this time of the year between the stallion installed and interlopers from other herds. When the battle is over the victor, himself bloody and bruised from savage bites and kicks, leads off the mares in a wild gallop over the steppe... We would often see kyangs by the thousand spread over the hillsides and looking inquisitively at our caravan; sometimes they would even surround us, though keeping at some distance."

Classification and subspecies

While some authorities recognize the kiang as a separate species, others regard it as a subspecies of Equus hemionus, the onager.

Three subspecies of Equus kiang commonly are recognized, and sometimes a fourth, the northern kiang:

- Western kiang, Equus kiang kiang (Moorcroft 1841)

- Eastern kiang, Equus kiang holdereri (Matschie 1911)

- Southern kiang, Equus kiang polyodon (Hodgson 1847)

- Northern kiang, Equus kiang chu (Hodgson 1893)

The four subspecies of kiang have geographically distinct populations and their morphology is different based on such features as skull proportions, angle of incisors, shape of rump, color pattern, coat color, and body size. The eastern kiang is the largest subspecies; the southern kiang is the smallest. The western kiang are slightly smaller than the eastern and also have a darker coat.

However, Shah et al. (2008) note that "these subspecies are probably not valid."

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Duncan, P. (ed.). 1992. Zebras, Asses, and Horses: An Action Plan for the Conservation of Wild Equids. IUCN/SSC Equid Specialist Group. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Grzimek, B., D.G. Kleiman, V. Geist, and M.C. McDade. Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Detroit: Thomson-Gale, 2004. ISBN 0307394913.

- Kawaguchi, E. 1909. Three Years in Tibet. Reprint: 1995, Delhi, India: Book Faith India. ISBN 8173030367.

- Moehlman, P.D. 2004. Equidae. In B. Grzimek, D.G. Kleiman, V. Geist, and M.C. McDade, Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Detroit: Thomson-Gale, 2004. ISBN 0307394913.

- Norbu, T.J., and H. Harrer. 1986. Tibet is My Country. London: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0861710452. (First published in German in 1960.)

- Savage, R. J. G., and M.R. Long. 1986. Mammal Evolution: An Illustrated Guide. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 081601194X.

- Shah, N., A. St. Louis, Z. Huibin, W. Bleisch, J. van Gruissen, and Q. Qureshi. 2008. Equus kiang In IUCN, 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- Sharma, B.D., J. Clevers, R. De Graaf, and N.R. Chapagain. 2004. Mapping Equus kiang (Tibetan wild ass) habitat in Surkhang, Upper Mustang, Nepal. Mountain Research and Development 24(2): 149–156.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.