Lassen Volcanic National Park

| Lassen Volcanic National Park | |

|---|---|

| IUCN Category II (National Park) | |

| | |

| Location: | Shasta, Lassen, Plumas, and Tehama Counties, California, USA |

| Nearest city: | Redding |

| Area: | 106,000 acres (42,900 ha) |

| Established: | August 9, 1916 |

| Visitation: | 395,057 (in 2007) |

| Governing body: | National Park Service |

Lassen Volcanic National Park is a United States National Park in northeastern California. The dominant feature of the park is Lassen Peak; the largest plug dome volcano in the world and the southern-most volcano in the Cascade Range. Lassen Peak erupted May 22, 1915, devastating nearby areas and raining volcanic ash as far away as 200 miles (320 km) to the east due to the prevailing wind. It was the most powerful series of eruptions from 1914 through 1917. They were the last to occur in the Cascade Mountains until the 1980 eruption of Mount Saint Helens.

The park is one of the few areas in the world where all four volcano types; plug dome, shield, cinder cone, and strato, of volcanoes can be found. The area surrounding Lassen Peak continues to be active with boiling mud pots, stinking fumaroles, and churning hot springs. Surrounding this active geologic activity are peaceful forests and untouched wilderness.

The Lassen area was first protected through designation as the Lassen Peak Forest Preserve. Lassen Volcanic National Park began as two separate national monuments designated by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1907 as: Cinder Cone National Monument and Lassen Peak National Monument. The two monuments were jointly designated a national park on August 9, 1916.

Lassen Peak

Lassen Peak, also known as Mount Lassen, is the southernmost active volcano in the Cascade Range. It is part of the Cascade Volcanic Arc, a chain of 13 large volcanic peaks that run from northern California to southwestern British Columbia.[1] Lassen is the largest of a group of more than 30 volcanic domes that have erupted over the past 300,000 years in the Lassen Volcanic Center.

Located in the Shasta Cascade region of Northern California, Lassen rises 2,000 feet (610 m) above the surrounding terrain and has a volume of half a cubic mile, making it one of the largest lava domes on Earth.[2] It was created on the destroyed northeastern flank of now gone Mount Tehama, a stratovolcano that was at least a thousand feet (300 m) higher than Lassen.

From 25,000 to 18,000 years ago, during the last glacial period of the current ice age, Lassen’s shape was significantly altered by glacial erosion. For example, the bowl-shaped depression on the volcano’s northeastern flank, called a cirque, was eroded by a glacier that extended out 7 miles (11 km) from the dome.[2] Unlike most lava domes, Lassen is topped by craters. A series of these craters exist around Lassen's summit, although two of these are now covered by solidified lava and sulfur deposits.

Lassen Peak has the distinction of being the only volcano in the Cascades other than Mount St. Helens in Washington state to erupt during the twentieth century. Its most recent eruptive period started in 1914, and lasted for seven years. The most powerful of these eruptions was a May 22, 1915, episode that sent ash and steam in a ten-kilometer-tall mushroom cloud, making it the largest recent eruption in the contiguous 48 U.S. states until the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens. The region remains geologically active, with mud pots, active fumaroles, and boiling water features, several of which are getting hotter. The area around Mount Lassen and nearby Mount Shasta are considered the most likely volcanoes in the Cascade Range to shift from dormancy to active eruptions.[1]

Lassen Volcanic National Park was created in Shasta County, California to preserve the devastated area and nearby volcanic wonders.

Geology

Formation of basement rocks

In the Cenozoic, uplifting and westward tilting of the Sierra Nevada along with extensive volcanism generated huge lahars (volcanic-derived mud flows) in the Pliocene which became the Tuscan Formation. This formation is not exposed anywhere in the national park but it is just below the surface in many areas.

Also in the Pliocene, basaltic flows erupted from vents and fissures in the southern part of the park. These and later flows covered increasingly large areas and built a lava plateau. In the later Pliocene and into the Pleistocene, these basaltic flows were covered by successive thick and fluid flows of andesite lava, which geologists call the Juniper lavas and the Twin Lakes lavas. The Twin Lakes lava is black, porphyritic, and has abundant xenocrysts of quartz.

Another group of andesite lava flows called the Flatiron, erupted during this time and covered the southwestern part of the park's area. The park by this time was a relatively featureless and large lava plain. Subsequently, the Eastern basalt flows erupted along the eastern boundary of what is now the park, forming low hills that were later eroded into rugged terrain.

Volcanoes rise

Pyroclastic eruptions then began to pile tephra into cones in the northern area of the park.

Mount Tehama (also known as Brokeoff Volcano) rose as a stratovolcano in the southeastern corner of the park during the Pleistocene. It was made of roughly alternating layers of andesitic lavas and tephra (volcanic ash, breccia, and pumice) with increasing amounts of tephra with elevation. At its height, Tehama was probably about 11,000 feet (3,400 m) high.

Approximately 350,000 years ago, its cone collapsed into itself and formed a two-mile (3.2 km) wide caldera after it emptied its throat and partially did the same to its magma chamber in a series of eruptions. One of these eruptions occurred where Lassen Peak now stands, and consisted of fluid, black, glassy dacite, which formed a layer 1,500 feet (460 m) thick, outcroppings of which can be seen as columnar rock at Lassen's base.

During glacial periods of the present Wisconsinan glaciation, glaciers have modified and helped to erode the older volcanoes in the park, including the remains of Tehama. Many of these glacial features, deposits and scars, however, have been covered by tephra and avalanches, or were destroyed by eruptions.

Roughly 27,000 years ago, Lassen Peak started to form as a dacite lava dome which quickly pushed its way through Tehama's destroyed north-eastern flank. As the lava dome pushed its way up, it shattered overlaying rock, which formed a blanket of talus around the emerging volcano. Lassen rose and reached its present height in a relatively short time, probably in as little as a few years. Lassen Peak has also been partially eroded by Ice Age glaciers, at least one of which extended as much as 7 miles (11 km) from the volcano itself.

Since then, smaller dacite domes formed around Lassen. The largest of these, Chaos Crags, is just north of Lassen Peak. Phreatic (steam explosion) eruptions, dacite and andesite lava flows and cinder cone formation have persisted into modern times.

Geography

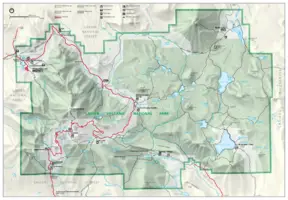

Lassen Volcanic National Park is located near the northern end of the Sacramento Valley. The western section of the park features great lava pinnacles, jagged craters, and steaming sulfur vents. It is cut by glaciated canyons and is dotted and threaded by lakes and rushing clear streams.

The eastern section of the park is a vast lava plateau more than one mile (1.6 km) above sea level. In this section are small cinder cones; Fairfield Peak, Hat Mountain, and Crater Butte. Forested with pine and fir, this area is studded with small lakes, but it boasts few streams. Warner Valley, marking the southern edge of the Lassen Plateau, features hot spring areas; Boiling Springs Lake, Devils Kitchen, and Terminal Geyser. This forested, steep valley also has large meadows bursting with wildflowers in the spring.

After emptying its throat and partially doing the same to its magma chamber in a series of eruptions, Tehama either collapsed into itself and formed a two-mile (3.2 km) wide caldera in the late Pleistocene or was simply eroded away with the help of acidic vapors that loosened and broke the rock, which was later carried away by glaciers. On the other side of the present caldera is Brokeoff Mountain (9,235 feet or 2,815 m), which is an erosional remnant of Mount Tehama and the second highest peak in the park. Mount Conrad, Mount Diller, and Pilot Pinnacle are also remnant peaks around the caldera.

Sulphur Works is a geothermal area between Lassen Peak and Brokeoff Mountain that is thought to mark an area near the center of Tehama's now-gone cone. Other geothermal areas in the caldera are Little Hot Springs Valley, Diamond Point (an old lava conduit), and Bumpass Hell.

There are four types of volcanoes in the world: Shield, plug dome, cinder cone, and composite. All four types are represented in the Park. Some of these include: Prospect Peak (shield), Lassen Peak (plug dome), Cinder Cone (cinder cone), and Brokeoff Volcano (composite).

Cinder Cone and the Fantastic Lava Beds, located about 10 miles (16 km) northeast of Lassen Peak, is a cinder cone volcano and associated lava flow field that last erupted about 1650. It created a series of basaltic andesite to andesite lava flows known as the Fantastic Lava Beds.

There are four shield volcanoes in the park; Mount Harkness in the southwest corner, Red Mountain at the south-central boundary, Prospect Peak in the northwest corner, and Raker Peak north of Lassen Peak. All of these volcanoes are 7,000-8,400 feet (2,133-2,560 m) above sea level and each is topped by a cinder cone volcano.

During ice ages, glaciers modified and helped to erode the older volcanoes in the park. The center of snow accumulation and therefore ice radiation was Lassen Peak, Red Mountain, and Raker Peak. These volcanoes thus show more glacial scarring than other volcanoes in the park.

Plant and animal life

Although the park is primarily known for its volcanic geology, there is also a rich diversity of plant and animal life. While the park is at the southern end of the Cascade Range geologic province, it is at the crossroads of three provinces: The Sierra Nevada mountains to the south and the Great Basin desert to the east in addition to the northward Cascades. Elevation, temperature, moisture, substrate (rock type and soil depth), and insolation (amount of sun) all play a part in providing a diverse array of habitats for varies species.

At elevations below 6,500 feet mixed conifer forest is the dominant vegetation. Included in this community are Ponderosa and Jeffrey pines, sugar pine, and white fir. Shrub and bush families include manzanita, gooseberry, and ceanothus. Wildflowers commonly found here include iris, spotted coralroot, lupine, pyrola, and violets.

Between elevations of 6,500 and 8,000 feet is red fir forest, home to red fir, western white pine, mountain hemlock, and lodgepole pine. Above 8,000 feet plants, with exposed patches of bare ground providing a harsh environment. Whitebark pine and Mountain hemlock are the trees at this elevation, along with hardy flowers including rock spirea, lupine, Indian paintbrush, and penstemon.

Over 700 flowering plant species in the park provide food and shelter for 300 vertebrates which includes birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and fish, as well as a host of invertebrates, including insects.

The park's mixed conifer forest provides home to black bear, mule deer, marten, brown creeper, mountain chickadee, white-headed woodpecker, long-toed salamander, and a wide variety of bat species. Higher elevations host Clark’s nutcracker, deer mice, various chipmunk species, gray-crowned rosy finch, pika, and golden mantled ground squirrel.

Valley bottoms, wet meadows, and stream and lake margins provide habitat for the Pacific tree frog, Western terrestrial garter snake, common snipe, and mountain pocket gopher.

Climate

Since the entire park is located at medium to high elevations, the park generally has cool-cold winters and warm summers below 7,500 feet (2,300 m). Above this elevation, the climate is harsh and cold, with cool summer temperatures. Precipitation within the park is high to very high due to a lack of a rain shadow from the Coast Ranges. The park gets more precipitation than anywhere in the Cascades south of the Three Sisters. Snowfall at the Lassen Peak Chalet at 6,700 feet (2,040 m) is around 430 inches (1,100 cm) despite facing east. Near Lake Helen, at 8,200 feet (2,500 m) the snowfall is around 600-700 inches (1500 cm to 1800 cm), making it probably the snowiest place in California. In addition, Lake Helen gets more average snow accumulation than any other recording station located near a volcano in the Cascade range, with a maximum of 178 inches (450 cm).[3] Snowbanks persist year-round, and while there are no glaciers currently, Lassen Peak does have 14 permanent snowfields.

Human history

Native Americans inhabited the area that became Lassen Volcanic National Park long before white settlers first saw Lassen. While the area was not conducive to year-round living due to adverse weather conditions and seasonally mobile deer populations, at least four tribes are known to have used the area as a meeting point: The Atsugewi, Yana, Yahi, and Maidu tribes.

These hunter-gatherers camped in the area in warmer months. Stone points, knives and metal tool artifacts remain. In 1911 a Yahi Indian named Ishi arrived in Oroville, California. He was believed to be the last stone age survivor in the United States. He lived his remaining days at the Anthropology Museum of the University of California in San Francisco, where he was an invaluable ethnological source.

Descendants of these tribes still live in the Lassen area and provide valuable insight to park management. [4]

Luis Argüello, a Spanish officer, was the first European to sight the peak, in 1821. The California gold rush brought the first settlers into the state. Pioneers used Lassen Peak as a landmark on their trek to the fertile Sacramento Valley. Peter Lassen, a Danish blacksmith settled in Northern California in the 1830s. In addition to guiding settlers through the surrounding area, he attempted to establish a city, and mining, power development projects, ranching, and timbering where likewise attempted. Lassen Peak is named after him. In 1851, William Nobles discovered an alternate route to northern California, passing through Lassen. Pioneer trails established by these two men are associated with the park. Sections of the Lassen and Nobles Emigrant Trail are still visible.[4]

B.F. Loomis documented Lassen Peak's early twentieth century eruption cycle. He photographed the eruptions, explored geologically, developed an extensive museum collection, and promoted the park's establishment.

The Lassen area was first protected through designation as the Lassen Peak Forest Preserve. Lassen Peak and Cinder Cone were later declared as U.S. National Monuments in May 1907, by President Theodore Roosevelt.[5]

The 29-mile (47 km) Main Park Road was constructed between 1925 and 1931, just 10 years after Lassen Peak erupted. Near Lassen Peak the road reaches 8,512 feet (2,594 m), making it the highest road in the Cascade Mountains.

In 1974, the United States Park Service took the advice of the U.S. Geological Survey and closed the visitor center and accommodations at Manzanita Lake. The Survey stated that these buildings would be in the way of a rockslide from Chaos Crags if an earthquake or eruption occurred in the area.[6] An aging seismograph station remains. However, a campground, store, and museum dedicated to Benjamin F. Loomis stands near Manzanita Lake, welcoming visitors who enter the park from the northwest entrance.

After the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption, the USGS intensified its monitoring of active and potentially active volcanoes in the Cascade Range. Monitoring of the Lassen area includes periodic measurements of ground deformation and volcanic-gas emissions and continuous transmission of data from a local network of nine seismometers to USGS offices in Menlo Park, California.[2] Should indications of a significant increase in volcanic activity be detected, the USGS will immediately deploy scientists and specially designed portable monitoring instruments to evaluate the threat. In addition, the National Park Service (NPS) has developed an emergency response plan that would be activated to protect the public in the event of an impending eruption.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 NASA Earth Observatory, Lassen Volcanic National Park. Retrieved October 11, 2008.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 US Geological Survey, Volcano Hazards of the Lassen Volcanic National Park Area, California. Retrieved October 10, 2008.

- ↑ Amar Andalkar, Cascade Snowfall and Snowdepth, Skiing the Cascade Volcanoes. Retrieved October 11, 2008.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 National Park Service, History & Culture. Retrieved October 11, 2008.

- ↑ Eugene P. Kiver, David V. Harris, and David V. Harris, Geology of U.S. Parklands (New York: J. Wiley, 1999).

- ↑ Harris, Geology of National Parks (1997).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Clynne, Michael A., Robert L. Christiansen, C. Dan Miller, Peter H. Stauffer, and James W. Hendley II. Volcano Hazards of the Lassen Volcanic National Park Area, California. U.S. Geological Survey. Fact Sheet 022-00, Online version 1.0 Retrieved October 10, 2008.

- Harris, Ann G., Esther Tuttle, and Sherwood D. Tuttle. 1997. Geology of National Parks. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Pub. Co. ISBN 9780787210656.

- National Park Service. Lassen Volcanic National Park. Retrieved October 10, 2008.

External links

All links retrieved October 25, 2022.

- NPS. Lassen Volcanic National Park

- University of California. Historic images of Lassen Volcanic National Park

| National parks of the United States | |

|---|---|

| Acadia • American Samoa • Arches • Badlands • Big Bend • Biscayne • Black Canyon of the Gunnison • Bryce Canyon • Canyonlands • Capitol Reef • Carlsbad Caverns • Channel Islands • Congaree • Crater Lake • Cuyahoga Valley • Death Valley • Denali • Dry Tortugas • Everglades • Gates of the Arctic • Glacier • Glacier Bay • Grand Canyon • Grand Teton • Great Basin • Great Sand Dunes • Great Smoky Mountains • Guadalupe Mountains • Haleakala • Hawaii Volcanoes • Hot Springs • Isle Royale • Joshua Tree • Katmai • Kenai Fjords • Kings Canyon • Kobuk Valley • Lake Clark • Lassen Volcanic • Mammoth Cave • Mesa Verde • Mount Rainier • North Cascades • Olympic • Petrified Forest • Redwood • Rocky Mountain • Saguaro • Sequoia • Shenandoah • Theodore Roosevelt • Virgin Islands • Voyageurs • Wind Cave • Wrangell-St. Elias • Yellowstone • Yosemite • Zion List by: date established, state |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.