Lei tai

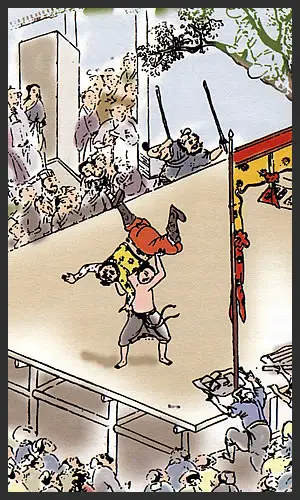

The Lèi tái (Traditional: 擂臺 Simplified: 擂台 “Beat (a drum) Platform”) is a raised fighting platform, without railings, where often fatal weapons and bare-knuckle Chinese martial arts tournaments were once held. The lei tai first appeared in its present form in China during the Song Dynasty.[1] However, ancient variations of it can be traced back to at least the Qin Dynasty (221-206 B.C.E.).[2] Officially sanctioned matches were presided over by a referee on the platform and judges on the sides. Fighters lost the match when they surrendered, were incapacitated, were thrown or otherwise forced from the stage. The winner would remain on the stage (as its "owner") unless ousted by a stronger opponent, and if there were no more challengers, he became the champion. Private duels on the stage had no rules and were sometimes fought to the death. In 1928, the Chinese government banned private duels and martial arts became an organized sport. Today, the lei tai is used in Sanshou and Kuoshu competitions throughout the world.

The absence of a railing or ropes makes the lei tai a unique fighting arena. There is no opportunity to trap an opponent in the turnbuckle, so the fighting strategy shifts away from power boxing to more evasive "circling" maneuvers. Sudden charges are not possible because a quick redirection will send a charging opponent flying off the stage. The platform is some distance off the floor, so fighters must deal with an added psychological factor when they approach the edge.[3]

| This article contains Chinese text. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Chinese characters. |

Etymology

Taken literally, lei tai means to “beat (a drum)." Tái means "stage" or "platform." It is also commonly referred to as a Dǎ lèi tái (Traditional: 打擂臺 Simplified: 打擂台—"Fight Beat, a drum, Platform"). The character for Dǎ combines the word for “robust or vigorous” (dīng 丁) with the radical for "hand" (shǒu 手). This can mean, "to strike, hit, beat, or fight." According to some martial arts groups, the Chinese character for Lèi (擂) combines the word for "thunder" (léi 雷) with the radical for "hand" (shǒu 手) and can mean, "to give an open challenge."[4] In Cantonese, using the Wade-Giles superscript number system, Lei tai is pronounced Leui4 Toi4. A common English rendering of this is "Lui Toi or Loey Toy."[5] Da lei tai is pronounced Da1 leui4 toi4 or Da2 leui4 toi4.

The Chinese military once used a Zhong Jun Lei Gu Tai (中军擂鼓台—“Central Military Drum Beating Platform”) to drum out commands on the battlefield and to tell time in the capital city[6] (see Gulou and Zhonglou). Three kingdoms general Zhang Fei used a stone “drum beating platform” to teach his soldiers troop movements.[7] It is possible that the lei tai received its name from this type of platform, since a superior fighter might "beat" his opponent like a drum.

Dimensions

The fighting area is square, but its exact size varies from source to source.

- The Swiss Open Kusohu Tournament states that classical lei tai fights took place on a stage at least 2.5 meters high with a four-sided area of 100 x 100 meters.

- The Tien Shan Pai Association states it was either 24 x 24 feet (7.3 m) or 30 x 30 feet (9.1 m) and 2 - 4 feet (1.2 m) high.

- The International Wushu Federation and Chinese Wushu Association commissions a lei tai which is 24 x 24 feet (7.3 m) and 2 feet (0.61 m) high. The surrounding mats are 6 feet (1.8 m) long and 1-foot (0.30 m) thick. It is called the "Nine Suns Mountain Sanda Lei tai." It was used in the 8th World Wushu Championships held in Vietnam in December 2005.[8]

- The International Chinese Kuoshu Federation uses a stage 24 x 24 feet (7.3 m) and 16 inches (410 mm) high.[9]

- According to the book Chinese Fast Wrestling for Fighting: The Art of San Shou Kuai Jiao Throws, Takedowns, & Ground-Fighting, it was 24 x 24 feet (7.3 m) and 5 feet (1.5 m) high.[10]

- The World Sports Encyclopedia says it is “an 8x8m platform … elevated approx. 6 m and surrounded by rubber walls.”[11]

Strategy

The lei tai is a unique fighting arena, different from the more typical ring or cage. The absence of a railing or ropes means that there is no opportunity to trap an opponent in the turnbuckle, so the fighting strategy shifts away from power boxing to more evasive "circling" maneuvers. It is not possible to simply charge an adversary; a quick redirection will send a charging opponent flying off the stage. The platform is some distance off the floor, and though it is surrounded by rubber mats, falling off can cause a painful injury, so fighters must deal with an added psychological factor when they approach the edge.[12]

Knocking an opponent off the lei tai, in the hope that they will fall and possibly be injured, is part of the fighting strategy.[13]

In a match on the lei tai, opponents continue to move against each other without interruption until one of them defeats the other. Sparring on the lei tai permits a kung fu student to demonstrate his or her understanding of the techniques, moves, rooting, breathing and control of anger. Kung fu together with lei tai trains the instincts and timing, and cultivates concentration and relaxation at the same time. The continuous movement of sanshou and kuoshu teaches practical combat applications of the disconnected moves learned from sets or Taolu ("Forms").

History (prior to 1928)

The lei tai first appeared during the Song Dynasty when it was used for boxing and Shuai Jiao exhibition matches and private duels.[1] According to the Chinese Kuoshu Institute (UK), an ancestor of the lei tai was used during the Qin Dynasty to hold Jiao Li wrestling competitions between imperial soldiers. The winner would be chosen to act as a bodyguard to the emperor or a martial arts instructor for the Imperial Military.[2]

The lei tai has long been a feature of Chinese martial arts. A boxer who wished to make himself known in a new village would build a lei tai, stand on it, and challenge all comers to try and knock him off.”[14] Some fighters issued their challenge in the form of a hand written letter to the person they wished to face. Martial artists conducted ‘challenge matches’ on the lei tai to test each other’s skills, settle a personal dispute, or prove the superiority of one martial arts system over another.[15] A fighter who fell off the platform, was forced off, or was knocked to the floor of the stage lost the match and his credibility as a teacher of boxing. The winner of the bout became the "owner of the platform" and remained on stage unless he was forced off himself by another opponent. If there were no more challengers, he became the champion and established the dominance of his style in that area. By defeating an already established master on the lei tai, a challenger could take over his school.[16]

In order to become a champion, a fighter had to defeat numerous opponents. At the end of the 19th century, legendary Lama Pai Grandmaster Wong Yan-Lam set up his own lei tai platform in front of Hai Tung Monastery in Guangdong after having gained a reputation as a bodyguard in Northern China. For 18 days, he fought against more than 150 other martial artists and was never defeated. Every challenger was maimed or killed. [17] Shortly afterward, he was elected leader of the Ten Tigers of Canton, the top ten kung fu practitioners in Guangdong.[18] After an unauthorized article claiming the superiority of Chen Style Tai chi appeared in the Beijing Times, 18th-generation Chen Style Tai chi Grandmaster Chen Zhao Pi (陈照丕) (1893–1972), third nephew of Chen Fake, set up a platform by Beijing’s “Xuan Wu Men”city gate, inviting all martial artists to challenge his skills. Over the course of 17 days, he defeated over 200 people and made many friends.[19]

Lei tai weapons and boxing matches were conducted without protective gear, like the Jissen Kumite (full-contact fighting) of Kyokushin karate. The absence of a rope or rail around the lei tai allowed a fighter to escape serious injury at the hands of a more powerful opponent by quickly leaping down from the stage and accepting a loss.[4] The fights sometimes continued until one of the boxers conceded defeat, was so severely injured that he could no longer fight, or was killed. On one occasion, described by Hung Gar Grandmaster Chiu Kow (1895-1995), father of Grandmaster Chiu Chi Ling, Hung Gar Master Leng Cai Yuk challenged a triad boss named Ha Saan fu, a master of internal martial arts who dealt in prostitution, gambling, and drugs, to a bout to halt the expansion of his criminal activities. The two men signed a contract stating that the fight could end in death, and Ha agreed to leave the area if he lost. After a few moments, Leng killed Ha. When Ha fell dead to the stage, his men tried to attack Leng and the local police quickly arrested him for his own protection.[20]

Modern lei tai (1928 to present)

In 1928, the Nationalist government banned the old tradition of private duels and contests on the lei tai because too many contestants were being killed. Martial arts then became an organized sport rather than a type of combat skill.[21]

National Boxing Competitions

In order to screen the best practitioners for teaching positions at the newly founded Central Kuoshu Institute (中南國術館), and in the provincial schools, Generals Zhang Zhi Jiang (张之江) (1882-1966), Li Lie Jun (李烈鈞) (1882-1946), and Li Jing Lin (李景林) (1884-1931) held the first modern full-contact national competition in October 1928. Many traditional masters refused to compete because they believed their skills could only be proven in serious duels and not in "sporting" contests. However, the event attracted hundreds of the best Chinese martial artists who participated in boxing, weapons and wrestling in a lei tai ring format. After the first several days, the fighting competitions were halted because two masters had been killed and many more were seriously injured. The final 12 contestants were not permitted to compete. The overall winner was voted on by a jury of his peers. Many of the "Top 15" finishers (some were Xingyi boxers) became teachers at the Institute.[22]

In 1929, the governor of Guangdong Province invited some of the Institutes' masters (including some of those that had competed in the 1928 lei tai) to establish a "Southern Kuoshu Institute." General Li Jinglin chose five masters to represent northern China, known as the Wu hu xia jiangnan (五虎下江南—"Five tigers heading south of Jiangnan"):

- Gu Ru Zhang (顾汝章) (1893-1952) of Northern Shaolin style. He was known as "Iron Palm Gu Ruzhang" and placed in the "Top 15" of the 1928 lei tai.

- Wan Lai Sheng (1903-1995) of Northern Shaolin and Internal styles (including Natural Boxing).

- Fu Zhen Song (傅振嵩) (1881-1953) of Baguazhang style.

- Wang Shao Zhou (王绍周) of Northern Shaolin and Cha styles.

- Li Xian Wu of Northern Shaolin and Internal styles.[21]

In 1933, the institute again hosted a national competition. The rules stated, "…if death occurs as a result of boxing injuries and fights, the coffin with a body of the deceased will be sent home."[23] Some of the top winners of this contest include:

- Chang Tung Sheng (1908-1986) of Shuai Jiao style. He won the heavy weight division and earned the martial nickname “Flying Butterfly.”[24]

- Wang Yu Shan (王玉山) (1892-1976) of Taichi Praying Mantis style.

- Li Kun Shan (1894-1976) of Plum Blossom Praying Mantis style.[22][21]

Kuoshu (Lei Tai Full-Contact Fighting)

In 1949, when the Communists took over China, the nationalist Chinese government moved to Taiwan, where, in 1955, it held a full-contact tournament, calling it lei tai. The original rules were used; there was no protective gear, and no weight class. Contestants drew numbers and fought whatever opponent they drew, regardless of weight and size. In 1975, Taiwan sponsored the first World Kuoshu Championship Tournament, and initiated weight class divisions. By 1992, Taiwan had already sponsored seven kuoshu lei tai fighting events.

Kuoshu was suppressed in mainland China during the Cultural Revolution, and martial arts was permitted only as a performance art. In 1979, when wushu was allowed to include self-defense training, practitioners began writing the rules for sanshou wushu tournaments, and the Communist government held a tournament called “sanshou.”

Kuoshu and sanshou differ mainly in their regulations; for example, kuoshu allows competitors to strike the same place twice, and sanshou does not. In 1986, at the fifth world tournament in Taiwan, so many competitors suffered broken noses and other severe injuries that the International Kuoshu Federation changed the rules to reduce injury. New rules have been in place since 1988.[25]

Sanshou / Sanda

Sanshou (Chinese: 散手; pinyin: sǎnshǒu; literally "free hand") or Sanda (Chinese: 散打; pinyin: sǎndǎ; literally "free fighting") originated in March of 1979, when the Zhejiang Provincial Sports Training Center, Beijing Physical Education University (former Beijing Physical Education Institute), and Wuhan Physical Education College were convened by the government China National Sport Committee (CNSC) to transform sanshou into a competitive sport. By October, the first three sanshou teams had been selected from among the fighters at the three colleges, and by May 1980 several more teams had been formed.

The first official rules of sanshou were drafted in January 1982 when the CNSC convened the National Sanshou Competition Rules Conference in Beijing. The first sanshou competition was held in November, 1982. The original fighting area was an open circle nine meters in diameter, but it was later changed to a traditional square lei tai.[26] Throwing someone off the lei tai in a Sanshou match automatically scores 3 points, the [points] equivalent of a spinning hook kick to the head, or a perfect foot sweep.[14]

Water lei tai

From May 22-26, 1999, the city of Taizhou, Zhejiang hosted the first "On Water Contest of the 'Liqun Cup' International Traditional Wushu and Unique Feats Tournament." Over a thousand competitors from 24 countries and 28 Chinese national teams gathered to test their skills against each other.

The water lei tai was held on the afternoon of the second day of competition. Instead of being surrounded with rubber mats, the lei tai was constructed over an outdoor pool, so that those who fell or were thrown off of the platform landed in water. There were five divisions and it was the most attended event of the tournament. Fighters were restricted to minimal safety equipment, only gloves and shorts. To improve safety, the water lei tai was a meter shorter than a standard one, which lessened the impact and allowed assistants to quickly jump in the pool to rescue any fighter who might have been unconscious.[4]

In March 2004, the 9th International Chinese Kuoshu Federation (ICKF) World Championship hosted the 3rd water lei tai. The tournament venue was the Aquatic Training Centre, Tainan Canal, Tainan, Taiwan. This was the first International event hosted by the ICKF to be held entirely on water.

See also

- Martial arts

- Wushu

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Eagleclaw.gr, Wushu History. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Chinese Kuoshu Institute, Shuai Jiao History. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ↑ Kung Fu Magazine, Kung Fu Magazine eXtreme Kungfu Qigong. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Kung Fu Magazine.com, Hard Qigong and Water Lei Tai Fights in China's Amazing New Tournament. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ↑ Kung Fu Magazine.com, The Kung Fu Glossary.

- ↑ Xian Travel, The Drum Tower. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ↑ China Natinal Tourist Office, Drum beating platform. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ↑ Kung Fu Supply, Nine Suns Mountain Sanda Leitai. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ↑ MHKung Fu, Leitai rules.

- ↑ Shou Yu Liang and Tai D. Ngo, Chinese Fast Wrestling for Fighting: The Art of San Shou Kuai Jiao Throws, Takedowns, & Ground-Fighting (YMAA Publication Center, 1997, ISBN 1-886969-49-3).

- ↑ Wojciech Liponski, World Sports Encyclopedia (MBI, 2003, ISBN 0760316821).

- ↑ Kung Fu Magazine, Kung Fu Magazine eXtreme Kungfu Qigong. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ↑ Dragon Door, Kettlebell Success—Martial Artist and Personal Trainer Steve Cotter. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Kung Fu Magazine, Salute to Wushu, Herb Borkland. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ↑ Jonathan Maberry, Ultimate Sparring: Principles & Practices (Strider Nolan Publishing, 2002, ISBN 1-932045-08-2).

- ↑ Fighting Arts, A Brief History of Chinese Kung-Fu: Part 2. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ↑ Kung Fu Magazine, Grandmaster David Chin's Legacy of Hop Gar Rebels and Guang Ping Tai Chi Revolutionaries. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ↑ www.liuhopafa.com, The Lama Style. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ↑ Davidine Sim, Siaw-Voon, and David Gaffney, Chen Style: The Source of Taijiquan (North Atlantic Books, 2001, ISBN 1556433778).

- ↑ Martin Sewer, Chiu Kow—Memorial Book 1895—1995 (Books on Demand, 2005, ISBN 3833428589).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Ottawa Kung Fu, Sports, Blood Sports and the Mixed Martial Arts.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Jwing Ming Yang and Jefferey A. Bolt, Shaolin Long Fist Kung Fu (Unique Publications, Inc., 1982, ISBN 0-86568-020-5).

- ↑ Mantis Boxing, Origins and the development of Praying Mantis Boxing. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ↑ www.changshuaichiao.com, Chang Tung Sheng Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ↑ Kung Fu Magazine, Full-Contact Kung Fu. Retrieved December 1, 2008.

- ↑ Wu Society, A Brief History of Sanshou. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gaffney, David, and Davidine Siaw-Voon Sim. Chen Style taijiquan: The Source of taiji Boxing. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books. 2002. ISBN 9781556433771.

- Liang, Shou Yu, and Tai D. Ngo. Chinese Fast Wrestling for Fighting: The Art of San Shou Kuai Jiao Throws, Takedowns, & Ground-Fighting. YMAA Publication Center, 1997. ISBN 1-886969-49-3.

- Lipoński, Wojciech. World Sports Encyclopedia. St. Paul, MN: MBI, 2003. ISBN 9780760316825.

- Maberry, Jonathan. Ultimate Sparring: Principles & Practices. Doylestown, Pa: Strider Nolan Pub, 2003. ISBN 9781932045086.

- Yang, Jwing-Ming, and Jeffery A. Bolt. Shaolin long fist kung fu = [Shao lin chʻang chʻüan]. Hollywood, CA: Unique Publications, 1981. ISBN 9780865680203.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.