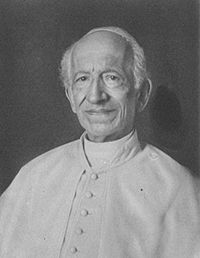

Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII (March 2, 1810 - July 20, 1903), born Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci, was the 256th Pope of the Roman Catholic Church, reigning from 1878 to 1903, succeeding Pope Pius IX. Reigning until the age of 93, he was the oldest pope, and had the third longest pontificate, behind his predecessor and John Paul II. He is known as the "Pope of the Working Man." He is perhaps best known for the concept of subsidiarity, the principle that everything that an authority does should aim to enhance human dignity and that power should reside and decisions should be taken at the lowest possible level. By defending the right to work and the right to reasonable wage and working condition, Leo XIII helped to re-position the Church as a defender of the working class, whereas earlier it had been closely identified with the elite. He was critical of both communism and capitalism. The latter required regulation to safeguard workers' rights; the former was godless, nor could all people be equally compensated, since people's abilities and skills are unequal. He is credited with opening up Catholic Church to engagement and dialogue with society, civil government, and with the world of science and secular learning.

Early life

Born in Carpineto Romano, near Rome, he was the sixth of the seven sons of Count Lodovico Pecci and his wife, Anna Prosperi Buzi. He received his doctorate in theology in 1836, and doctorates of civil and Canon Law in Rome. While in the minor orders, he was appointed domestic prelate to Pope Gregory XVI in January 1837. He was ordained priest on December 31, 1837, by the Vicar of Rome, became titular archbishop of Damietta in 1843, and apostolic nuncio to Belgium on January 28, 1843. In that country, the school question was then warmly debated between the Catholic majority and the Liberal minority. Pecci encouraged the struggle for Catholic schools, yet he was able to win the good will of the Court, not only of the pious Queen Louise, but also of King Leopold I, who was strongly liberal in his views. The new nuncio succeeded in uniting the Catholics. Upon his initiative, a Belgian College in Rome was opened in 1844.

Pecci was named papal assistant in 1843. He first achieved note as the popular and successful Archbishop of Perugia from 1846 till 1877, during which period he had to cope, among others, with the earthquake and subsequent famine that hit Umbria in 1854. In addition to his post in Perugia, he was appointed Cardinal-Priest of S. Crisogono in 1853.

In August 1877, on the death of Cardinal De Angelis, Pope Pius IX appointed him camerlengo, so that he was obliged to reside in Rome. Pope Pius died February 7, 1878, and during his closing years the Liberal press had often insinuated that the Italian Government should take a hand in the conclave and occupy the Vatican. However, the Russo-Turkish War and the sudden death of Victor Emmanuel II (January 9, 1878) distracted the attention of the government, the conclave proceeded as usual, and after the three scrutinies Cardinal Pecci was elected by forty-four votes out of sixty-one.

Papacy

| Styles of Pope Leo XIII | |

| |

| Reference style | His Holiness |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness |

| Religious style | Holy Father |

| Posthumous style | none |

Leo XIII worked to encourage understanding between the Church and the modern world. He firmly re-asserted the scholastic doctrine that science and religion co-exist, and required the study of Thomas Aquinas.[1] Although he had stated that it "is quite unlawful to demand, defend, or to grant unconditional freedom of thought, or speech, of writing or worship, as if these were so many rights given by nature to man," he opened the Vatican Secret Archives to qualified researchers, among whom was the noted historian of the Papacy Ludwig von Pastor. Leo XIII was also the first Pope to come out strongly in favor of the French Republic, upsetting many French monarchists, but his support for democracy did not necessarily imply his acceptance of egalitarianism: "People differ in capacity, skill, health, strength; and unequal fortune is a necessary result of unequal condition. Such inequality is far from being disadvantageous either to individuals or to the community."[2] His relations with the Italian state were less progressive; Leo XIII continued the Papacy's self-imposed incarceration in the Vatican stance, and continued to insist that Italian Catholics should not vote in Italian elections or hold elected office. In his first consistory, in 1879, he elevated his older brother, Giuseppe, to a cardinal.

Leo XIII was the first Pope of whom a sound recording was made. The recording can be found on a compact disc of Alessandro Moreschi's singing; a recording of his performance of the Ave Maria.[3] He was also the first Pope to be filmed on a motion picture camera. He was filmed by its inventor, W.K. Dickson, and he blessed the camera afterward.

Beatification and canonizations

He beatified Saint Gerard Majella in 1893, and Saint Edmund Campion in 1886. In addition, he canonized the following saints:

- 1881: Clare of Montefalco (d. 1308), John Baptist de Rossi (1696-1764), and Lawrence of Brindisi (d. 1619)

- 1883: Benedict Joseph Labre (1748-1783)

- 1888: Seven Holy Founders of the Servite Order, Peter Claver (1561-1654), John Berchmans (1599-1621), and Alphonsus Rodriguez (1531-1617)

- 1890: Blessed Giovenale Ancina (1545-1604)

- 1897: Anthony M. Zaccaria (1502-1539) and Peter Fourier of Our Lady (1565-1640)

- 1900: John Baptist de la Salle (1651-1719) and Rita of Cascia (1381-1457)

Papal teachings and publications

Leo XIII is most famous for his social teaching, in which he argued that both capitalism and communism are flawed. The former is flawed unless safeguards to uphold social justice are in place. The latter is godless. His encyclical Rerum Novarum focused on the rights and duties of capital and labor, and introduced the idea of subsidiarity into Catholic social thought. He encouraged the formation of lay-associations among the Catholic rank and file. On the other hand, he insisted on papal authority over that of national Catholic hierarchies, and on the importance of the Papal Legates, or Nuncios, to each national hierarchy.

A full list of all of Leo's encyclicals can be found in the List of Encyclicals of Pope Leo XIII.

In his 1893 encyclical, Providentissimus Deus, Leo gave new encouragement to Bible study while warning against rationalist interpretations which deny the inspiration of Scripture:

"For all the books which the Church receives as sacred and canonical, are written wholly and entirely, with all their parts, at the dictation of the Holy Ghost: and so far is it from being possible that any error can co-exist with inspiration, that inspiration not only is essentially incompatible with error, but excludes and rejects it as absolutely and necessarily as it is impossible that God Himself, the supreme Truth, can utter that which is not true (Providentissimus Deus).

The 1896 bull, Apostolicae Curae, declared the ordination of deacons, priests, and bishops in Anglican churches (including the Church of England) invalid, while granting recognition to ordinations in the Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches although they were considered illicit. However, he was interested in the possibility of reconciliation with the Anglican communion, and entered into conversations on unity.

His 1899 apostolic letter, Testem Benevolentiae, condemned the heresy called Americanism. Some American Catholics were accused of advocating such principles as the total freedom of the press, separation of church and state, and other liberal ideas that were though inconsistent with the doctrines of the church.

Relations with the United Kingdom and the Americas

Among the activities of Leo XIII that were important for the English-speaking world, one might certainly count the encyclical "Apostolicæ Curæ" of 1896, on the non-validity of the Anglican orders. Furthermore, Leo restored the Scottish hierarchy in 1878. In British India, he established a Catholic hierarchy, in 1886, and regulated some long-standing conflicts with the Portuguese authorities.

The United States at many moments in time attracted the attention and admiration of Pope Leo. He confirmed the decrees of the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore (1884), and raised to the cardinalate Archbishop Gibbons of that city in 1886. Leo was not present at Washington on the occasion of the foundation of the Catholic University of America. His role in South America will also be remembered, especially the First Plenary Council of Latin America, held at Rome in 1899, and his encyclical of 1888, to the bishops of Brazil on the abolition of slavery.

American newspapers criticized Pope Leo because of his attempt to gain control of American public schools. One cartoonist drew Leo as a fox unable to reach grapes that were labeled for American schools; the caption read "Sour grapes!"

The number of states with diplomatic mission in the Vatican increased during Leo's papacy. Non-Christian nations also started to enter into diplomatic relations.

Audiences

- While on a pilgrimage with her father and sister in 1887, the future Saint Thérèse of Lisieux, during a general audience with Pope Leo XIII, asked him to allow her to enter the Carmelite order. Even though she was strictly forbidden to speak to him because she was told it would prolong the audience too much, in her autobiography, Story of a Soul, she wrote that after she kissed his slipper and he presented his hand, instead of kissing it, she took it in her own hand and said through tears, "Most Holy Father, I have a great favor to ask you. In honor of your Jubilee, permit me to enter Carmel at the age of 15!" Pope Leo XIII answered, "Well, my child, do what the superiors decide." Thérèse replied, "Oh! Holy Father, if you say yes, everybody will agree!" Finally, the Pope said, "Go… go… You will enter if God wills it" [italics hers] after which time, two guards lifted Thérèse (still on her knees in front of the Pope) by her arms and carried her to the door where a third gave her a medal of the Pope. Shortly thereafter, the Bishop of Bayeux authorized the prioress to receive Thérèse, and in April 1888, she entered Carmel at the age of 15.

- While known for his cheerful personality, Leo also had a gentle sense of humor as well. During one of his audiences, a man claimed to have had the opportunity to see Pius IX at one of his last audiences before his death in 1878. Upon hearing the remarkable story, Leo smiled and replied, "If I had known that you were so dangerous to popes, I would have postponed this audience further."

Legacy

Leo XIII was the first Pope to be born in the nineteenth century. He was also the first to die in the twentieth century: He lived to the age of 93, making him the longest-lived Pope. At the time of his death, Leo XIII was the second-longest reigning Pope, exceeded only by his immediate predecessor, Pius IX (unless one counts St. Peter as having reigned from the time that Jesus is said to have given him "the keys to the kingdom" until his death, rather than from his arrival in Rome). Leo's regal length was subsequently exceeded by that of Pope John Paul II on March 14, 2004.

Leo was not entombed in St. Peter's Basilica, as all popes after him were, but instead at St. John Lateran, a church in which he took a particular interest.

Born in the nineteenth century and still Pope in the opening years of the twentieth, Leo XIII's most significant contribution lies in his effort to reposition the church as a defender of the poor rather than as the guardian of the rich, elite, and powerful. This emphasized the church's pastoral mission, which he helped to strengthen. His concern to reconcile the teachings of the church with new ideas about social justice and democracy as well as with scientific advances encouraged his successors to look for ways of rethinking how it understood the relationship between theological truth, and general knowledge.

Notes

- ↑ Pope Leo XIII, Aeterna Patris. Retrieved October 9, 2007.

- ↑ leo XIII, Rerum Novarum. Retrieved October 9, 2007.

- ↑ Leo XIII, Ave Maria. Retrieved October 9, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Benigni, U. "Pope Leo XIII." In Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume IX. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910.

- Leo XIII and the Modern World. Eastbourne, East Sussex: Gardners Books, 2007. ISBN 9780548144985

- O'Reilly, Bernard. Life of Leo XIII—From An Authentic Memoir—Furnished By His Order. New York: Charles L. Webster & Company, 1887.

- Thérèse, of Lisieux, Saint. Story of a Soul—The Autobiography of St. Thérèse of Lisieux. Washington, DC: ICS Publications, 1996. ISBN 9780935216103

- Quardt, Robert. Der Meisterdiplomat. Translated by Ilya Wolston. New York: Alba House, 1964

External links

All links retrieved October 25, 2022.

- Pope Leo XIII texts and biography from the Vatican

- Pope Leo XIII: text with concordances and frequency list.

| ||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.