Libya

| ليبيا / Libya / ⵍⵉⴱⵢⴰ Libya |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Anthem: Libya, Libya, Libya |

||||

| Capital | Tripoli | |||

| Official languages | Arabic[a] | |||

| Spoken languages | Libyan Arabic, other Arabic dialects, Berber | |||

| Demonym | Libyan | |||

| Government | Disputed | |||

| - | Chairman of the Presidency Council | Fayez al-Sarraj (Tobruk) | ||

| - | Prime Minister | Fayez al-Sarraj (Tobruk) | ||

| - | Chairman of the New General National Congress | Nouri Abusahmain (Tripoli) | ||

| - | Acting Prime Minister | Khalifa al-Ghawi (Tripoli) | ||

| Legislature | Council of Deputies (Tobruk) General National Congress (2014) (Tripoli) |

|||

| Formation | ||||

| - | Independence from Italy | February 10, 1947 | ||

| - | Released from British and French oversight[b] | December 24, 1951 | ||

| - | Coup d'état by Muammar Gaddafi | September 1, 1969 | ||

| - | Revolution Day | February 17, 2011 | ||

| - | Battle of Tripoli | August 28, 2011 | ||

| - | Handover to the General National Congress | August 8, 2012 | ||

| Area | ||||

| - | Total | 1,759,541 km² (17th) 679,359 sq mi |

||

| Population | ||||

| - | 2015 estimate | 6,411,776[1] (108th) | ||

| - | 2006 census | 5,658,000 | ||

| - | Density | 3.55/km² (218th) 9.2/sq mi |

||

| GDP (PPP) | 2015 estimate | |||

| - | Total | $92.875 billion[2] | ||

| - | Per capita | $14,854[2] | ||

| GDP (nominal) | 2015 estimate | |||

| - | Total | $29.721 billion[2] | ||

| - | Per capita | $4,754[2] (97th) | ||

| Currency | Dinar (LYD) |

|||

| Time zone | CET [c] (UTC+1) | |||

| - | Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

| Internet TLD | .ly | |||

| Calling code | [[+218]] | |||

| a. ^ Libyan Arabic and other varieties. Berber languages in certain low-populated areas. The official language is simply identified as "Arabic" (Constitutional Declaration, article 1). b. ^ The UK and France held a joint condominium over Libya through the United Nations Trusteeship Council. |

||||

Libya is a country in North Africa 90 percent of which is desert. The name "Libya" is an indigenous (Berber) one. Egyptian texts refer to ![]() , R'bw (Libu), which refers to one of the tribes of Berber peoples living west of the Nile River. In Greek, the tribesmen were called Libyes and their country became "Libya," although in ancient Greece the term had a broader meaning, encompassing all of North Africa west of Egypt.

, R'bw (Libu), which refers to one of the tribes of Berber peoples living west of the Nile River. In Greek, the tribesmen were called Libyes and their country became "Libya," although in ancient Greece the term had a broader meaning, encompassing all of North Africa west of Egypt.

Libya has one of the highest Gross Domestic Products per person in Africa, largely because of its large petroleum reserves. The country was led for over 40 years by Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi, whose foreign policy often brought him into conflict with the West and governments of other African countries. However, Libya publicly gave up any nuclear aspirations after the U.S. invasion of Iraq, and Libya's foreign relations today are less contentious.

Geography

Libya extends over 679,182 square miles (1,759,540 sq km), making it the fourth largest country in Africa by area and the seventeenth largest nation in the world by size. Libya is somewhat smaller than Indonesia, and roughly the size of the U.S. state of Alaska. It is bounded to the north by the Mediterranean Sea, the west by Tunisia and Algeria, the southwest by Niger, the south by Chad and Sudan, and to the east by Egypt. At 1,100 miles (1,770 km), Libya's coastline is the longest of any African country bordering the Mediterranean.

The climate is mostly dry and desert-like in nature. However, the northern regions enjoy a milder Mediterranean climate. Natural hazards come in the form of hot, dry, dust-laden sirocco (known in Libya as the gibli), a southern wind blowing from one to four days in spring and autumn. There are also dust storms and sandstorms.

With the discovery of oil in the 1950s also came the discovery of a massive aquifer underneath much of the country. The water in this aquifer, which predates the last ice ages and the Sahara Desert, is being pumped through a pipeline to the north to be used for agriculture. The country is also home to the Arkenu craters, double impact craters found in the desert. Oases can be found scattered throughout Libya, the most important of which are Ghadames and Kufra.

Three regions

The three traditional parts of the country are Tripolitania, the Fezzan, and Cyrenaica, each with its own topography and history. Tripolitania, in the northwest, includes a strip along the coastline that is an important agricultural region, where grains, vegetables, and groves of such crops as olives, dates, almonds, and citrus fruits are grown. The largest city in Libya, Tripoli, is in this region, and nearly a third of the population lives close to it. Tripoli is also the capital. Inland, the land rises into plains and the limestone hills of Jebel Nefusah, then joins the Red Desert, a wide rocky plateau of red sandstone.

The Fezzan area, which makes up most of southwestern Libya, contains vast sand dunes (ergs), all that remains of mountains from 600 million year ago that were eroded by sea water, which once covered the region, and wind. Occasional oases provided a haven for nomads in traditional times.

Cyrenaica, in the northeast, covers nearly half of Libya and includes the city of Benghazi, the second largest in the country and a major seaport and oil refining center. South of the coastal agricultural strip, the land rises to a rocky plateau that extends south to the Libyan Desert.

Libyan Desert

The Libyan Desert, which covers much of eastern Libya, is one of the most arid places on earth. In places, decades may pass without rain, and even in the highlands rainfall happens erratically, once every five to ten years. Temperatures can be extreme; in 1922, the town of Al 'Aziziyah, west of Tripoli, recorded an air temperature of 136°F (57.8°C), generally accepted as the highest recorded naturally occurring air temperature reached on Earth.

There are a few scattered, uninhabited small oases, usually linked to the major depressions, where water can be found by digging down a few feet.

Flora and fauna

The plants and animals found in Libya are primarily those that can survive in a harsh climate. Plants include cacti and date palms. Animals are those such as camels, snakes, lizards, jerboa, foxes, wildcats, and hyenas that can live in the desert. Birds include vultures, hawks, and sandgrouse.

History

Classical period

Archaeological evidence indicates that from as early as the eighth millennium B.C.E., Libya's coastal plain was inhabited by a Neolithic people who were skilled in the domestication of cattle and the cultivation of crops. This culture flourished for thousands of years in the region, until they were displaced or absorbed by the Berbers.

The area known in modern times as Libya was later occupied by a series of peoples, with the Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Greeks, Romans, Vandals, and Byzantines ruling all or part of the area. Although the Greeks and Romans left ruins at Cyrene, Leptis Magna, and Sabratha, little other evidence remains of these ancient cultures.

The Phoenicians were the first to establish trading posts in Libya, when the merchants of Tyre (in present-day Lebanon) developed commercial relations with the Berber tribes and made treaties with them to ensure their cooperation in the exploitation of raw materials. By the fifth century B.C.E., Carthage, the greatest of the Phoenician colonies, had extended its hegemony across much of Northern Africa, where a distinctive civilization, known as Punic, came into being. Punic settlements on the Libyan coast included Oea (Tripoli), Libdah (Leptis Magna), and Sabratha. All these were in an area that was later called Tripolis, or "Three Cities." Libya's current-day capital Tripoli takes its name from this.

The Greeks conquered eastern Libya when, according to tradition, emigrants from the crowded island of Thera were commanded by the oracle at Delphi to seek a new home in North Africa. In 631 B.C.E., they founded the city of Cyrene. Within two hundred years, four more important Greek cities were established in the area: Barce (Al Marj); Euhesperides (later Berenice, present-day Benghazi); Teuchira (later Arsinoe, present-day Tukrah); and Apollonia (Susah), the port of Cyrene. Together with Cyrene, they were known as the Pentapolis (Five Cities).

The Romans unified both regions of Libya, and for more than four hundred years Tripolitania and Cyrenaica became prosperous Roman provinces. Roman ruins, such as those of Leptis Magna, attest to the vitality of the region, where populous cities and even small towns enjoyed the amenities of urban life. Merchants and artisans from many parts of the Roman world established themselves in North Africa, but the character of the cities of Tripolitania remained decidedly Punic and, in Cyrenaica, Greek.

Even as far back as the Carthaginian era, trade routes existed across the Sahara Desert to the Niger River bend. The caravans returned on the so-called Garamantian Way laden with ivory, gold, rare woods and feathers, and other precious items that were shipped to various parts of the world. In later periods, slaves were added to this trans-Saharan trade. The main item of value the merchants traded was salt.

Arab rule

Arabs conquered Libya in the seventh century C.E. In the following centuries, many of the indigenous peoples adopted Islam, as well as the Arabic language and culture. The Ottoman Turks conquered the country in the mid-sixteenth century, and the three states or "Wilayat" of Tripolitania, Cyrenaica, and Fezzan (which make up Libya) remained part of their empire with the exception of the virtual autonomy of the Karamanlis, who ruled from 1711 until 1835, mainly in Tripolitania, but had influence in Cyrenaica and Fezzan as well, at the peak their reign (mid eighteenth century).

This constituted a first glimpse in recent history of the united and independent Libya that was to re-emerge two centuries later. Ironically, reunification came about through the unlikely route of an invasion and occupation, starting in 1911 when Italy turned the three regions into colonies. In 1934, Italy adopted the name "Libya" (used by the Greeks for all of North Africa except Egypt) as the official name of the colony. King Idris I, Emir of Cyrenaica, led Libyan resistance to Italian occupation between the two World Wars. From 1943 to 1951, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were under British administration, while the French controlled Fezzan. In 1944, Idris returned from exile in Cairo but declined to resume permanent residence in Cyrenaica until the removal of some aspects of foreign control in 1947. Under the terms of the 1947 peace treaty with the Allies, Italy relinquished all claims to Libya.

Independence

On November 21, 1949, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution stating that Libya should become independent before January 1, 1952. Idris represented Libya in the subsequent UN negotiations. On December 24, 1951, Libya declared its independence as the United Kingdom of Libya, a constitutional and hereditary monarchy.

The discovery of significant oil reserves in 1959 and the subsequent income from petroleum sales enabled one of the world's poorest nations to establish an extremely wealthy state. Although oil drastically improved the Libyan government's finances, popular resentment began to build over the increased concentration of the nation's wealth in the hands of King Idris and the national elite. This discontent continued to mount with the rise of Nasserism and Arab nationalism throughout North Africa and the Middle East.

Revolutionary period

On September 1, 1969, a small group of military officers led by then 28-year-old army officer Muammar Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi staged a coup d’état against King Idris. At the time, Idris was in Turkey for medical treatment. His nephew, Crown Prince Sayyid Hasan ar-Rida al-Mahdi as-Sanussi, became king. Sayyid quickly found that he had substantially less power as the new king than he had had as a prince. Before long, Sayyid Hasan ar-Rida had been formally deposed by the revolutionary army officers and put under house arrest. Meanwhile, revolutionary officers abolished the monarchy and proclaimed the new Libyan Arab Republic. Gaddafi was, and is to this day, referred to as the "Brother Leader and Guide of the Revolution" in government statements and the official press.

Colonel Gaddafi in power

For the first seven years following the revolution, Colonel Gaddafi and twelve fellow army officers, the Revolutionary Command Council, began a complete overhaul of Libya's political system, society, and economy. In 1977, Qaddafi convened a General People's Congress (GPC) to proclaim the establishment of "people's power," change the country's name to the Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, and to give primary authority in the GPC, at least theoretically. Today, the official name of the country of Libya is Al Jumahiriyah al Arabiyah al Libiyah ash Shabiyah al Ishtirakiyah al Uzma.

Gaddafi remained the de facto chief of state and secretary general of the GPC until 1980, when he gave up his office. He continued to control all aspects of the Libyan government through direct appeals to the masses, a pervasive security apparatus, and powerful revolutionary committees. Although he held no formal office, Gaddafi exercised absolute power with the assistance of a small group of trusted advisers, who included relatives from his home base in the Surt region, which lies between the rival provinces of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica.

He also attempted to achieve greater popular participation in local government. In 1973, he announced the start of a "cultural revolution" in schools, businesses, industries, and public institutions to oversee administration of those organizations in the public interest. The March 1977 establishment of "people's power" —with mandatory popular participation in the selection of representatives to the GPC— was the culmination of this process.

An abortive coup attempt in May 1984, apparently mounted by Libyan exiles with internal support, led to a short-lived reign of terror in which thousands were imprisoned and interrogated. An unknown number were executed. Gadddafi used the revolutionary committees to search out alleged internal opponents following the coup attempt, thereby accelerating the rise of more radical elements inside the Libyan power hierarchy.

In 1988, faced with rising public dissatisfaction with shortages in consumer goods and setbacks in Libya's war with Chad, Gaddafi began to curb the power of the revolutionary committees and to institute some domestic reforms. The regime released many political prisoners and eased restrictions on foreign travel by Libyans. Private businesses were again permitted to operate.

In the late 1980s, Gaddafi began to pursue an anti-fundamentalist Islamic policy domestically, viewing fundamentalism as a potential rallying point for opponents of the regime. Ministerial positions and military commanders were frequently shuffled or placed under temporary house arrest to diffuse potential threats to Gaddafi's authority. The military, once Gaddafi's strongest supporters, became a potential threat in the 1990s. In 1993, following a failed coup attempt that implicated senior military officers, Gaddafi began to purge the military periodically, eliminating potential rivals and inserting his own loyal followers in their place.

2011 Revolution

After popular movements overturned the rulers of Tunisia and Egypt, its immediate neighbors to the west and east, Libya experienced a full-scale revolt beginning in February 2011. The National Transitional Council was established under the stewardship of Mustafa Abdul Jalil, Gaddafi's former justice minister, to administer the areas of Libya under rebel control. By August 2011, rebel fighters had entered Tripoli. However, Gaddafi asserted that he was still in Libya and would not concede power to the rebels.

The last bastion of Gaddafi's rule, the coastal city of Sirte, fell to anti-Gaddafi fighters on October 20th and Muammar Gaddafi was reportedly shot and killed.

The "liberation" of Libya was celebrated on 23 October 2011, and Mahmoud Jibril, who had served as the National Transition Council's de facto head of government, announced that consultations were under way to form an interim government within one month, followed by elections for a constitutional assembly within eight months and parliamentary and presidential elections to be held within a year after that. He stepped down as expected the same day and was succeeded by Ali Tarhouni as interim Prime Minister.

Post-Gaddafi era

Since the defeat of loyalist forces, Libya has been torn among numerous rival, armed militias affiliated with distinct regions, cities and tribes, while the central government has been weak and unable to effectively exert its authority over the country. Competing militias have pitted themselves against each other in a political struggle between Islamist politicians and their opponents. On July 7, 2012, Libyans held their first parliamentary elections since the end of the former regime. On August 8, 2012, the National Transitional Council officially handed power over to the wholly elected General National Congress, which was then tasked with the formation of an interim government and the drafting of a new Libyan Constitution to be approved in a general referendum.

On August 25, 2012, in what Reuters reported as "the most blatant sectarian attack" since the end of the civil war, unnamed organized assailants bulldozed a Sufi mosque with graves, in broad daylight in the center of the Libyan capital Tripoli. It was the second such razing of a Sufi site in two days.[3]

On September 11, 2012, Islamist militants mounted a surprise attack on the American consulate in Benghazi, killing the U.S. ambassador to Libya, J. Christopher Stevens, and three others. The incident generated outrage in the United States and Libya.[4][5]

On October 7, 2012, Libya's Prime Minister-elect Mustafa A.G. Abushagur was ousted after failing a second time to win parliamentary approval for a new cabinet.[6] On October 14, 2012, the General National Congress elected former GNC member and human rights lawyer Ali Zeidan as prime minister-designate. Zeidan was sworn in after his cabinet was approved by the GNC.[7] On March 11, 2014, after having been ousted by the GNC for his inability to halt a rogue oil shipment, Prime Minister Zeiden stepped down, and was replaced by Prime Minister Abdullah al-Thani.[8] On March 25, 2014, in the face of mounting instability, al-Thani's government briefly explored the possibility of the restoration of the Libyan monarchy.[9]

In June 2014, elections were held to the Council of Deputies, a new legislative body intended to take over from the General National Congress. The elections were marred by violence and low turnout, with voting stations closed in some areas.[10] Secularists and liberals did well in the elections, to the consternation of Islamist lawmakers in the GNC, who reconvened and declared a continuing mandate for the GNC, refusing to recognize the new Council of Deputies.[11] Armed supporters of the General National Congress occupied Tripoli, forcing the newly elected parliament to flee to Tobruk.[12]

Libya has been riven by conflict between the rival parliaments since mid-2014. Tribal militias and jihadist groups have taken advantage of the power vacuum. Most notably, radical Islamist fighters seized Derna in 2014 and Sirte in 2015 in the name of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. In early 2015, neighboring Egypt launched airstrikes against ISIL in support of the Tobruk government.[13]

In January 2015, meetings were held with the aim to find a peaceful agreement between the rival parties in Libya. The so-called Geneva-Ghadames talks were supposed to bring the GNC and the Tobruk government together at one table to find a solution of the internal conflict. However, the GNC actually never participated, a sign that internal division not only affected the "Tobruk Camp," but also the "Tripoli Camp." Meanwhile, terrorism within Libya steadily increased, affecting also neighboring countries.

During 2015 an extended series of diplomatic meetings and peace negotiations were supported by the United Nations, as conducted by the Special Representative of the Secretary-General (SRSG), Spanish diplomat Bernardino Leon.[14] Talks, negotiations and dialogue continued on during mid-2015 at various international locations, culminating at Skhirat in Morocco in early September.[15]

Politics

As a result of the civil war of February to October 2011 and the collapse of the Gaddafi regime which had been in power for more than 40 years, Libya is administrated by a caretaker government, known as the National Transitional Council.

Under Gaddafi, there were two branches of government in Libya. The "revolutionary sector" of Revolutionary Leader Gaddafi, the Revolutionary Committees, and the remaining members of the 12-person Revolutionary Command Council that was established in 1969. The historical revolutionary leadership was not elected and could be voted out of office; they were in power by virtue of their involvement in the revolution. The revolutionary sector dictated the decision-making power of the second sector, the "Jamahiriya Sector."

Constituting the legislative branch of government, this sector comprised Local People's Congresses in each of the 1,500 urban wards, 32 Sha'biyat People's Congresses for the regions, and the National General People's Congress. These legislative bodies were represented by corresponding executive bodies (Local People's Committees, Sha'biyat People's Committees, and the National General People's Committee/Cabinet).

Every four years, the membership of the Local People's Congresses elected their own leaders and the secretaries for the People's Committees. The leadership of the Local People's Congress represents the local congress at the People's Congress of the next level. The members of the National General People's Congress elected the members of the National General People's Committee (the Cabinet) at their annual meeting.

The government controled both state-run and semi-autonomous media. In cases involving a violation of "certain taboos," the private press, like The Tripoli Post, has been censored, although articles that are critical of government policies are sometimes requested and intentionally published by the revolutionary leadership as a means of initiating reforms.

Political parties were banned in 1972. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are allowed but their numbers are small because they are required to conform to the goals of the revolution. Trade unions do not exist, but numerous professional associations are integrated into the state structure as a third pillar, along with the People's Congresses and Committees. Professional associations send delegates to the General People's Congress.

In 2011, the National Transitional Council was formed to represent Libya by anti-Gaddafi forces during the 2011 Libyan civil war. In March it declared itself to be the "sole representative of all Libya," and on September 16, the United Nations switched its official recognition to the NTC.

Foreign relations

Libya's foreign policies have undergone much fluctuation and change since the state was proclaimed in 1951. As a kingdom, Libya maintained a pro-Western stance yet was recognized as belonging to the conservative traditionalist bloc in the Arab League, which it joined in 1953.

Since 1969, Colonel Muammar Gaddafi determined Libya's foreign policy. His principal foreign policy goals were Arab unity, elimination of Israel, advancement of Islam, support for Palestinians, elimination of outside—particularly Western—influence in the Middle East and Africa, and support for a range of "revolutionary" causes.

U.S.-Libyan relations became increasingly strained because of Libya's foreign policies supporting international terrorism and subversion against moderate Arab and African governments. Gaddafi closed American and British bases on Libyan territory and partially nationalized all foreign oil and commercial interests in Libya.

Gaddafi played a key role in promoting the use of oil embargoes as a political weapon for challenging the West, hoping that an oil price rise and embargo in 1973 would persuade the West—especially the United States—to end support for Israel. Gaddafi rejected both Soviet communism and Western capitalism and claimed he was charting a middle course.

In October 1978, Gaddafi sent Libyan troops to aid Idi Amin in the Uganda-Tanzania war, when Amin tried to annex the northern Tanzanian province of Kagera and Tanzania counterattacked. Amin lost the battle and later fled to exile in Libya, where he remained for almost a year.

Libya also was one of the main supporters of the Polisario Front in the former Spanish Sahara—a nationalist group dedicated to ending Spanish colonialism in the region. The Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) was proclaimed by the Polisario on February 28, 1976, and Libya recognized the SADR as the legitimate government of Western Sahara in 1980.

The U.S. government declared Libya a "state sponsor of terrorism" on December 29, 1979.

Support for rebel and paramilitary groups

The government of Libya has also received enormous criticism and trade restrictions for allegedly providing numerous armed rebel groups with weapons, explosives, and combat training. The ideologies of some of these organizations have varied greatly. Though most seem to be nationalist, with some having a socialist ideology, while others hold a more conservative and Islamic fundamentalist ideology.

Paramilitaries supported by Libya past and present include:

- The Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) of Northern Ireland, a left-wing Irish paramilitary group that fought a 29-year war for a United Ireland. Note that many of the breakaway Irish Republican groups that oppose the Good Friday Agreement are believed to possess a significant amount of Libyan ammunition and semtex explosives that was delivered to the IRA during the 1970s and 1980s.

- The Palestine Liberation Organization of the Israeli-occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip received support from Libya, as well as many other Arab states.

- The Moro National Liberation Front was a right-wing Islamic fundamentalist rebel army that fought in the Philippines against the military dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos.

- Umkhonto we Sizwe - Xhosa, for the "spear of the nation," was originally the military wing of the African National Congress, which fought against the white apartheid regime in South Africa. During the years of underground struggle, the group was supported by Libya.

- ETA - Basque Fatherland and Liberty, a left-wing Basque separatist group fighting for the independence of the Basques from Spain, also had ties to the Provisional Irish Republican Army.

- The Polisario Front in the former Spanish Sahara (now known as Western Sahara).

In 1988, Libya was found to be in the process of constructing a chemical weapons plant at Rabta, a plant which is now the largest such facility in the Third World. As of January 2002, Libya was constructing another chemical weapons production facility at Tarhunah. Citing Libya's support for terrorism and its past regional aggressions, the United States voiced concern over this development. In cooperation with like-minded countries, the United States has since sought to bring a halt to the foreign technical assistance deemed essential to the completion of this facility.

Libya's relationship with the former Soviet Union involved massive Libyan arms purchases from the Soviet bloc and the presence of thousands of east bloc advisers. Libya's use—and heavy loss—of Soviet-supplied weaponry in its war with Chad was a notable breach of an apparent Soviet-Libyan understanding not to use the weapons for activities inconsistent with Soviet objectives. As a result, Soviet-Libyan relations reached a nadir in mid-1987.

There have been no credible reports of Libyan involvement in terrorism since 1994, and Libya has taken significant steps to mend its international image.

After the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Union, Libya concentrated on expanding diplomatic ties with Third World countries and increasing its commercial links with Europe and East Asia. Following the imposition of UN sanctions in 1992, these ties significantly diminished. Following a 1998 Arab League meeting in which fellow Arab states decided not to challenge U.N. sanctions, Gaddafi announced that he was turning his back on pan-Arab ideas, one of the fundamental tenets of his philosophy.

Instead, Libya pursued closer bilateral ties, particularly with Egypt and North African nations Tunisia and Morocco. It also has sought to develop its relations with Sub-Saharan Africa, leading to Libyan involvement in several internal African disputes in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, Somalia, Central African Republic, Eritrea, and Ethiopia. Libya also has sought to expand its influence in Africa through financial assistance, ranging from aid donations to impoverished neighbors such as Niger to oil subsidies to Zimbabwe. Gaddafi has proposed a borderless "United States of Africa" to transform the continent into a single nation-state ruled by a single government. This plan has been moderately well received, although more powerful would-be participants such as Nigeria and South Africa are skeptical.

Border conflicts

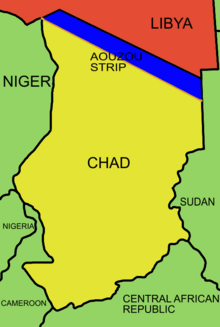

Libya had long claimed the Aouzou Strip, land in northern Chad rich with uranium deposits. In 1973, Libya engaged in military operations in the Aouzou Strip to gain access to minerals and to use it as a base of influence in Chadian politics. Chadian forces were able to force the Libyans to retreat from the Aouzou Strip in 1987. A cease-fire between Chad and Libya held from 1987 to 1988, followed by unsuccessful negotiations over the next several years, leading finally to the 1994 International Court of Justice decision granting Chad sovereignty over the Aouzou Strip, which ended Libyan occupation.

Libya claims about 19,400 km² in northern Niger and part of southeastern Algeria. In addition, it is involved in a maritime boundary dispute with Tunisia.

Relations with the West

In the 1980s, Libya increasingly distanced itself from the West and was accused of committing mass acts of state-sponsored terrorism. When evidence of Libyan complicity was discovered in the Berlin discotheque terrorist bombing that killed two American servicemen, the United States responded by launching an aerial bombing attack against targets near Tripoli and Benghazi in April 1986.

In 1991, two Libyan intelligence agents were indicted by federal prosecutors in the United States and Scotland for their involvement in the December 1988 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103. Six other Libyans were put on trial in absentia for the 1989 bombing of UTA Flight 772. The UN Security Council demanded that Libya surrender the suspects, cooperate with the Pan Am 103 and UTA 772 investigations, pay compensation to the victims' families, and cease all support for terrorism. Libya's refusal to comply led to the imposition of sanctions.

In 2003, more than a decade after the sanctions were put in place, Libya began to make dramatic policy changes vis-à-vis the Western world with the open intention of pursuing a Western-Libyan détente. The Libyan government announced its decision to abandon its weapons of mass destruction programs and pay almost $3 billion in compensation to the families of Flights 103 and 772. The decision was welcomed by many Western nations and was seen as an important step for Libya toward rejoining the international community.

Since 2003 the country has made efforts to normalize its ties with the European Union and the United States and has even coined the catchphrase "The Libya Model," an example intended to show the world what can be achieved through negotiation rather than force when there is goodwill on both sides. The United States removed Libya's name from the list of state sponsors of terrorism and restored full diplomatic relations in 2006.

Human rights

According to the U.S. Department of State’s annual human rights report for 2006, Libya’s authoritarian regime continued to have a poor record in the area of human rights. Citizens did not have the right to change their government. Reported torture, arbitrary arrest, and incommunicado detention remained problems. The government restricted civil liberties and freedoms of speech, press, assembly, and association. Other problems included poor prison conditions; impunity for government officials; lengthy political detention; denial of fair public trial; infringement of privacy rights; restrictions of freedom of religion; corruption and lack of transparency; societal discrimination against women, ethnic minorities, and foreign workers; trafficking in persons; and restriction of labor rights. In 2005, Freedom House rated political rights and civil liberties in Libya as "7" (least free).

HIV trials

Five Bulgarian nurses and a Palestinian doctor were charged with intentionally infecting 426 Libyan children with HIV at a Benghazi children's hospital, as part of a supposed plot by the West to destabilize the regime. All were sentenced to death. The court's methods were criticized by a number of human rights organizations and its verdicts condemned by the United States and the European Union. In July 2007, the sentences were commuted to life imprisonment. After prolonged and complex negotiations, all were released and arrived in Bulgaria, where they were pardoned.

Administrative divisions

Libya was divided into several governorates (muhafazat) before being split into 25 municipalities (baladiyat) Recently, Libya was divided into 32 sha'biyah. These were then further rearranged into twenty-two districts in 2007.

Economy

The Libyan economy depends primarily upon revenues from the oil sector, which constitutes practically all export earnings and about one-quarter of gross domestic product (GDP). These oil revenues and a small population give Libya one of the highest GDPs per person in Africa and have allowed the Libyan state to provide an extensive and impressive level of social security, particularly in the fields of housing and education.

Compared to its neighbors, Libya enjoys an extremely low level of both absolute and relative poverty. Libyan officials have carried out economic reforms as part of a broader campaign to reintegrate the country into the global capitalist economy. This effort picked up steam after UN sanctions were lifted in September 2003, and Libya announced in December 2003 that it would abandon programs to build weapons of mass destruction.

Libya has begun some market-oriented reforms. Initial steps have included applying for membership of the World Trade Organization, reducing subsidies, and announcing plans for privatization. The non-oil manufacturing and construction sectors, which account for about 20 percent of GDP, have expanded from processing mostly agricultural products to include the production of petrochemicals, iron, steel, and aluminium. Climatic conditions and poor soils severely limit agricultural output, and Libya imports about 75 percent of its food. Water is also a problem; some 28 percent of the population lacks access to safe drinking water.

Under former prime ministers Shukri Ghanem and Baghdadi Mahmudi, Libya underwent a business boom with many government-run industries being privatized. Many international oil companies returned to the country, including oil giants Shell and ExxonMobil. Tourism increased, bringing demand for hotel accommodations and for greater capacity at airports such as Tripoli International. A multimillion-dollar renovation of Libyan airports was approved by the government to help meet such demands. Libya has long been a difficult country for western tourists to visit due to stringent visa requirements. Since the 2011 protests there has been revived hope that an open society will encourage the return of tourists.

Demographics

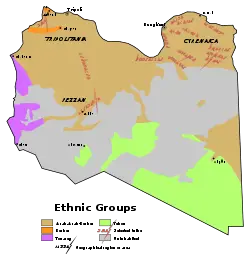

Libya has a small population within its large territory, with a population density of about 8.5 per square mile (3 people per square kilometer) in the two northern regions of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, and 1.6 per square mile (less than 1 per square kilometer) elsewhere. Libya is thus one of the least dense nations by area in the world. Some 90 percent of the people live in less than 10 percent of the area, mostly along the coast. More than half the population is urban, concentrated in the two largest cities, Tripoli and Benghazi. Native Libyans are a mixture of indigenous Berber peoples and the later arriving Arabs.

Some Libyans are descended from marriages of Turkish soldiers to Libyan women. Black Libyans are descendants of slaves brought to the country during the days of the slave trade. Some worked the gardens in the southern oases and on the farms along the coast. Others were taken in by Bedouin tribes or merchant families as retainers and domestics.

Berber peoples form a large but less distinguishable minority. The original inhabitants in most of North Africa, they were overrun in the eleventh and twelfth centuries by the Bedouin Arab armies of the expanding Islamic empire. Over the centuries, the Berber population largely fused with the conquering Arabs, but evidence of Berber culture remains. The herdsmen and traders of the great Tuareg confederation are found in the south. Known as the "Blue Men of the Desert," their distinctive blue dress and the practice of men veiling themselves distinguish them from the rest of the population. Historically autonomous and fiercely independent, they stand apart from other Libyans and maintain links to their homelands in the Tibesti and Ahaggar mountain retreats of the central Sahara, living nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyles.

Among foreign residents, the largest groups are citizens of other African nations, including North Africans (primarily Egyptians and Tunisians), and sub-Saharan Africans. Berbers and Arabs constitute 97 percent of the population; the other 3 percent are Greeks, Maltese, Italians, Egyptians, Afghans, Turks, Indians, and sub-Saharan Africans.

The main language spoken is Arabic, which is also the official language. Tamazight (i.e., Berber languages), which do not have official status, are spoken by Libyan Berbers. In addition, Tuaregs speak Tamahaq. Italian and English are sometimes spoken in the big cities, although Italian speakers are mainly among the older generation.

Family life is important for Libyan families, the majority of which live in apartment blocks and other independent housing units. Although the Libyan Arabs traditionally lived nomadic lifestyles in tents, they have now settled in various towns and cities. Because of this, their old ways of life are gradually fading out. An unknown small number of Libyans still live in the desert as their families have done for centuries. Most of the population has occupations in industry and services, and a small percentage is involved in agriculture.

Education

Education in Libya is free for all citizens and compulsory up until secondary level. The literacy rate is the highest in North Africa; over 88 percent of the population can read and write. After Libya's independence in 1951, its first university, the University of Libya, was established in Benghazi.

Libya's population includes 1.7 million students, over 270,000 of whom study at the tertiary level. The rapid increase in the number of students in the higher education sector since independence has been mirrored by an increase in the number of institutions of higher education. Since 1975 the number of universities has grown from two to nine and after their introduction in 1980, the number of higher technical and vocational institutes currently stands at 84 (with 12 public universities). Libya's higher education is financed by the public budget. In 1998 the budget allocated for education represented 38.2 percent of the national budget. The main universities in Libya are Al Fateh University (Tripoli) and Garyounis University (Benghazi).

Religion

Muslims make up 97 percent of the population, the vast majority of them adhering to Sunni Islam, which provides both a spiritual guide for individuals and a keystone for government policy, but a minority (between 5 and 10 percent) adheres to Ibadism (a branch of Kharijism). This minority, both linguistic and religious, suffers from a lack of consideration by the official authorities.

Gaddafi asserts that he is a devout Muslim, and his government supports Islamic institutions and worldwide proselytizing on behalf of Islam. Libyan Islam, however, has always been considered traditional, but in no way harsh compared to Islam in other countries. A Libyan form of Sufism is also common in parts of the country.

There are also very small Christian communities, composed almost exclusively of foreigners. There is a small Anglican community, made up mostly of African immigrant workers in Tripoli; it is part of the Egyptian Diocese. There are also an estimated forty thousand Roman Catholics in Libya who are served by two bishops, one in Tripoli (serving the Italian community) and one in Benghazi (serving the Maltese community).

Libya was until recent times the home of one of the oldest Jewish communities in the world, dating back to at least 300 B.C.E. A series of pogroms beginning in November 1945 lasted for almost three years and drastically reduced Libya's Jewish population. In 1948, about 38,000 Jews remained in the country. Upon Libya's independence in 1951, most of the Jewish community emigrated. After the Suez Crisis in 1956, all but about 100 Jews were forced to flee.

Culture

Libya is culturally similar to its neighboring Maghreb states. Libyans consider themselves very much a part of a wider Arab community. The Libyan state tends to strengthen this feeling by considering Arabic as the only official language and forbidding the teaching and even the use of the Berber language. Libyan Arabs have a heritage in the traditions of the nomadic Bedouin and associate themselves with a particular Bedouin tribe.

As with some other countries in the Arab world, Libya boasts few theaters or art galleries. Public entertainment is almost nonexistent, even in the big cities. Recently however, there has been a revival of the arts in Libya, especially painting: private galleries are springing up to provide a showcase for new talent. Conversely, for many years there have been no public theaters, and only a few cinemas showing foreign films.

The tradition of folk culture is still alive and well, with troupes performing music and dance at frequent festivals, both in Libya and abroad. The main output of Libyan television is devoted to showing various styles of traditional Libyan music. Tuareg music and dance are popular in Ghadames and the south. Libyan television programs are mostly in Arabic, with a 30-minute news broadcast each evening in English and French. The government maintains strict control over all media outlets. An analysis by the Committee to Protect Journalists found Libya’s media the most tightly controlled in the Arab world.

Many Libyans frequent the country's beaches. They also visit Libya's beautifully preserved archaeological sites-—especially Leptis Magna, widely considered one of the best-preserved Roman archaeological sites in the world.

The nation's capital, Tripoli, boasts many good museums and archives; these include the Government Library, the Ethnographic Museum, the Archaeological Museum, the National Archives, the Epigraphy Museum, and the Islamic Museum. The Jamahiriya Museum, built in consultation with UNESCO, may be the country's most famous. It houses one of the finest collections of classical art in the Mediterranean.

Notes

- ↑ CIA, Libya World Fact Book.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 International Monetary Fund, Libya.

- ↑ Taha Zargoun, Fighters bulldoze Sufi mosque in central Tripoli Reuters, August 25, 2012.

- ↑ Sarah Aarthun, 4 hours of fire and chaos: How the Benghazi attack unfolded CNN, September 13, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- ↑ Phil Vinter, 'This does not represent us': Pro-American rallies in Libya after terrorist attack that killed ambassador Chris Stevens The Daily Mail, September 13, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- ↑ Libyan Prime Minister Mustafa Abu Shagur dismissed BBC News, October 7, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- ↑ Libya congress approves new PM's proposed government Reuters, October 31, 2012.

- ↑ Libya ex-PM Zeidan 'leaves country despite travel ban' BBC, March 12, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- ↑ Anna Mahjar-Barducci, Libya: Restoring the Monarchy? Gatestone Institute, April 16, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- ↑ Rana Jawad, Libyan elections: Low turnout marks bid to end political crisis BBC, June 26, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- ↑ Former Libyan parliament reconvenes, elects Islamist premier Al Akhbar English, August 25, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- ↑ Chris Stephen, Libyan parliament takes refuge in Greek car ferry The Guardian, September 9, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- ↑ Laura Dean, How strong is the Islamic State in Libya? USA Today, February 20, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- ↑ Libya warring factions meet face to face for first time PressTV, June 29, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- ↑ Tom Miles, U.N. sees Libya talks entering final mile, eyes Sept. 20 deal Reuters, September 4, 2015.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ham, Anthony. Libya. Melbourne: Lonely Planet, 2002. ISBN 0864426992

- Azema, James. Libya Handbook: The Travel Guide. Footprint handbooks. Bath: Footprint, 2000. ISBN 1900949776

- Harris, David A. In the Trenches: Selected Speeches and Writings of an American Jewish Activist. Hoboken, NJ: KTAV Pub. House, 2000. ISBN 0881256935

- Rogerson, Barnaby. A Traveller's History of North Africa. New York, NY: Interlink Books, 1998. ISBN 156656252X

- Wright, John L. Libya (Nations of the Modern World). New York, NY: Praeger, 1969. ISBN 978-0510395216

External links

All links retrieved October 25, 2022.

- World Statesmen. Libya

- Population of Libyan Municipalities

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.