Lithuania

| Lietuvos Respublika Republic of Lithuania |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: "Tautos jėga vienybėje" "The strength of the nation lies in unity" |

||||||

| Anthem: Tautiška giesmė National Hymn |

||||||

| Location of Lithuania (orange) – on the European continent (camel white) – in the European Union (camel) [Legend] |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Vilnius 54°41′N 25°19′E | |||||

| Official languages | Lithuanian | |||||

| Ethnic groups (2011) | 83.9% Lithuanians, 6.6% Poles, 5.4% Russians, 1.3% Belarusians, 3.8% others and unspecified[1] |

|||||

| Demonym | Lithuanian | |||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic[2] | |||||

| - | President | Dalia Grybauskaitė | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Andrius Kubilius | ||||

| - | Seimas Speaker | Irena Degutienė | ||||

| Independence | from Russia and Germany (1918) | |||||

| - | First mention of Lithuania | 9 March 1009 | ||||

| - | Coronation of Mindaugas | 6 July 1253 | ||||

| - | Personal union with Poland | 2 February 1386 | ||||

| - | Creation of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth | 1569 | ||||

| - | Partitions of the Commonwealth | 1795 | ||||

| - | Independence declared | 16 February 1918 | ||||

| - | 1st and 2nd Soviet occupations | 15 June 1940 and again 1944 | ||||

| - | Nazi German occupation | 22 June 1941 | ||||

| - | Independence restored | 11 March 1990 | ||||

| EU accession | 1 May 2004 | |||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 65,200 km² (123rd) 25,174 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 1.35% | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2011 estimate | 3,203,857[3] (133rd) | ||||

| - | 2002 census | 3,483,972 | ||||

| - | Density | 50.3/km² (120th) 141.2/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2011 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $59.825 billion[4] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $18,278[4] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2011 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $40.333 billion[4] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $12,323[4] | ||||

| Gini (2003) | 36 (medium) | |||||

| Currency | Lithuanian litas (Lt) (LTL) |

|||||

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .lt1 | |||||

| Calling code | [[+370]] | |||||

| 1 | Also .eu, shared with other European Union member states. | |||||

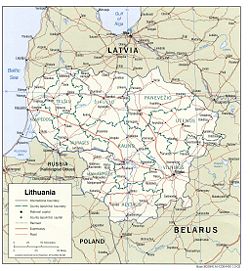

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in northern Europe. Situated along the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea, it shares borders with Latvia to the north, Belarus to the southeast, Poland, and the Russian exclave of the Kaliningrad Oblast to the southwest.

Occupied by both Germany and the Soviet Union, Lithuania lost over 780,000 residents between 1940 and 1954. Of them, an estimated 120,000 to 300,000 were killed or exiled to Siberia by the Soviets, while others chose to emigrate to western nations. Lithuania experienced one of the worst death rates of the Holocaust.

A part of the Soviet Republics until its collapse in 1991, Lithuania has made headway in its recovery from this system. In 2003, prior to joining the European Union, Lithuania had the highest economic growth rate amongst all candidate and member countries, reaching 8.8 percent in the third quarter. It became a member state of the European Union in May 2004.

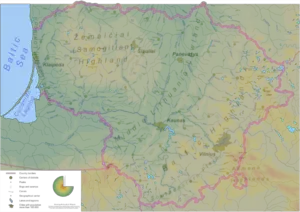

Geography

The largest and most populous of the Baltic states, Lithuania has 67 miles (108 kilometers) of sandy coastline, of which only 24 miles (39 km) face the open Baltic Sea, between Latvia and Russia. Lithuania's major warm-water port of Klaipėda lies at the narrow mouth of Curonian Lagoon, a shallow lagoon extending south to Kaliningrad and separated from the Baltic sea by Curonian Spit, where Kuršių Nerija National Park was established for its remarkable sand dunes.

Physical environment

Lithuania is situated on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania's boundaries have changed several times since 1918, but they have been stable since 1945. Currently, Lithuania covers an area of about 25,175 square miles (65,200 square kilometers). About the size of the American state of West Virginia, it is larger than Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, or Switzerland.

Lithuania's northern neighbor is Latvia. The two countries share a border that extends 282 miles (453 kilometers). Lithuania's eastern border with Belarus is longer, stretching 312 miles (502 km). The border with Poland on the south is relatively short, only 56 miles (91 km), but is very busy because of international traffic. Lithuania also has a 141 mile (227 km) border with Russia. Russian territory adjacent to Lithuania is Kaliningrad Oblast, which is the northern part of the former German East Prussia, including the city of Kaliningrad. Finally, Lithuania has 67 miles (108 km) of Baltic seashore with an ice-free harbor at Klaipėda. The Baltic coast offers sandy beaches and pine forests which attract thousands of vacationers each year.

Topography, drainage, and climate

Lithuania lies at the edge of the East European Plain. Its landscape was smoothed by the glaciers of the last Ice Age, which retreated about 25,000-22,000 years B.C.E. Lithuania's terrain alternates between moderate lowlands and highlands. The highest elevation is 974 feet (297 meters) above sea level, in the eastern part of the republic and separated from the uplands of the western region of Samogitia by the very fertile plains of the southwestern and central regions. The landscape is punctuated by 2,833 lakes larger than 107,640 ft² (10,000 m²) and 1,600 smaller ponds. The majority of the lakes are found in the eastern part of the country.

Lithuania also has 758 rivers longer than 6 miles (ten km). The largest river is the Nemunas, with a total length of 570 miles (917 km), originating in Belarus. The Nemunas and some of its tributaries are used for internal shipping (in 2000, 89 inland ships carried 900,000 tons of cargo, which is less than 1 percent of the total goods traffic). The other larger waterways are the Neris at 320 miles (510 km), Venta at 215 miles (346 km), and Šešupė at 185 miles (298 km). However, only 375 miles (600 km) of Lithuania's rivers are navigable.

Once a heavily forested land, Lithuania's territory today consists of only 28 percent woodlands—primarily pine, spruce, and birch forests. Ash and oak are very scarce. The forests are rich in mushrooms and berries, as well as a variety of plants. Between 56.27 and 53.53 latitude and 20.56 and 26.50 longitude, Lithuania's landscape was smoothed by glaciers, except for morainic hills in the western uplands and eastern highlands. The terrain is marked by numerous small lakes and swamps, and a mixed forest zone covers 30 percent of the country. The growing season lasts 169 days in the east and 202 days in the west, with most farmland consisting of sandy- or clay-loam soils. Limestone, clay, sand, and gravel are Lithuania's primary natural resources, but the coastal shelf offers perhaps 1.6 million m³ (10 million barrels) of oil deposits, and the southeast could provide high yields of iron ore and granite. According to some geographers, the Geographical Center of Europe is just north of Lithuania's capital, Vilnius.

The country's climate, which ranges between maritime and continental, is relatively mild. Average temperatures on the coast are 35° Fahrenheit (1.6 °C) in January and 64°F (17.8°C) in July. In Vilnius the average temperatures are 35.8°F (2.1°C) in January and 64.6°F (18.1°C) in July. The average annual precipitation is 28 inches (717 millimeters) along the coast and 19 inches (490 millimeters) inland. Temperature records from the Baltic area cover about 250 years. The data show that there were warm periods during the latter half of the 18th century, and that the 19th century was a relatively cool period. An early 20th century warming culminated in the 1930s, followed by a smaller cooling that lasted until the 1960s. A warming trend has persisted since then.[5]

Lithuania experienced a drought in 2002, causing forest and peat bog fires.[6] The country suffered along with the rest of Northwestern Europe during a heat wave in the summer of 2006.

The environment

Concerned with slowing environmental deterioration, Lithuania has created several national parks and reservations. The country's flora and fauna have suffered, however, from extensive drainage of land for agricultural use. Other environmental problems were created by the development of environmentally unsafe industries, including the Ignalina nuclear power plant, which still operates two reactors similar to those at Chernobyl, and the chemical and other industries that pollute the air and empty wastes into rivers and lakes. According to calculations by experts, about one-third of Lithuanian territory is covered by polluted air at any given time. Problems exist mainly in the cities, such as Vilnius, Kaunas, Jonava, Mažeikiai, Elektrėnai, and Naujoji Akmenė—the sites of fertilizer and other chemical plants, an oil refinery, power station, and a cement factory.

Water quality has also been an issue. The city of Kaunas, with a population of about 400,000, had no water purification plant until 1999; sewage was sent directly into the Neman River. Tertiary wastewater treatment is scheduled to begin in 2007. River and lake pollution are other legacies of Soviet exploitation of the environment. The Courland Lagoon, for example, separated from the Baltic Sea by a strip of high dunes and pine forests, is about 85 percent contaminated. Beaches in the Baltic resorts are frequently closed to swimming because of contamination. Forests around the cities of Jonava, Mažeikiai, and Elektrėnai (the chemical, oil, and power-generation centers) are affected by acid rain.

Lithuania was among the first of the Soviet Republics to introduce environmental regulations. However, because of Moscow's emphasis on increasing production and because of numerous local violations, technological backwardness, and political apathy, serious environmental problems now exist.

Natural resources

Lithuania has limited natural resources. The republic has an abundance of limestone, clay, quartz sand, gypsum sand, and dolomite, which are suitable for making high-quality cement, glass, and ceramics. There also is an ample supply of mineral water, but energy sources and industrial materials are all in short supply. Oil was discovered in Lithuania in the 1950s, but only a few wells operate, and all that do are located in the western part of the country. It is estimated that the Baltic Sea shelf and the western region of Lithuania hold commercially viable amounts of oil, but if exploited this oil would satisfy only about 20 percent of Lithuania's annual need for petroleum products for the next twenty years. Lithuania has a large amount of thermal energy along the Baltic Sea coast, however, which could be used to heat hundreds of thousands of homes, as is done in Iceland. In addition, iron ore deposits have been found in the southern region. But commercial exploitation of these deposits probably would require strip mining, which is environmentally unsound. Moreover, exploitation of these resources will depend on Lithuania's ability to attract capital and technology from abroad.

Natural resources:' peat, arable land

Land use:

- arable land: 35%

- permanent crops: 12%

- permanent pastures: 7%

- forests and woodland: 31%

- other: 15% (1993 est.)

Irrigated land: 430 km² (1993 est.)

History

Early History

Lithuania entered into European history when it was first mentioned in a medieval German manuscript, the Quedlinburg Chronicle, on February, 14, 1009. The Lithuanian lands were united by Mindaugas in 1236, and neighboring countries referred to it as "the state of Lithuania." The official coronation of Mindaugas as King of Lithuania, on July 6, 1253, marked its recognition by Christendom, and the official recognition of Lithuanian statehood as the Kingdom of Lithuania.[7]

During the early period of the Gediminas (1316-1430), the state occupied the territories of present-day Belarus, Ukraine, and parts of Poland and Russia. By the end of the fourteenth century, Lithuania was the largest country in Europe. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania stretched across a substantial part of Europe, from the Baltic to the Black Sea. Lithuanian nobility, city dwellers, and peasants accepted Christianity in 1385, following Poland's offer of its crown to Jogaila, the Grand Duke of Lithuania. Grand Duke Jogaila was crowned King of Poland on February 2, 1386. Lithuania and Poland were joined into a personal union, as both countries were ruled by the same Jagiellon Dynasty.

In 1401, the formal union was dissolved as a result of disputes over legal terminology, and Vytautas, the cousin of Jogaila, became the Grand Duke of Lithuania. The closely allied armies of Poland and Lithuania achieved a great victory over Teutonic Knights in 1410 at the Battle of Grunwald, the biggest battle in medieval Europe.

A royal crown had been bestowed upon Vytautas in 1429 by Sigismund, the Holy Roman Emperor, but Polish magnates prevented the coronation of Vytautas, seizing the crown as it was being brought to him. A new crown was ordered from Germany and a new date set for the coronation, but a month later Vytautas died in an accident.

As a result of the growing centralized power of the Grand Principality of Moscow, in 1569, Lithuania and Poland formally united into a single dual state called the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. As a member of the Commonwealth, Lithuania retained its sovereignty and its institutions, including a separate army, currency, and statutory law which was codified in three Statutes of Lithuania.[8] In 1795, the joint state was dissolved by the third Partition of the Commonwealth, which forfeited its lands to Russia, Prussia and Austria, under duress. Over 90 percent of Lithuania was incorporated into the Russian Empire and the remainder into Prussia.

Modern history

On February 16, 1918, Lithuania re-established its independence. From July, 1918, until November of that year, Monaco-born King Mindaugas II was pronounced the titular monarch of Lithuania, until the country's parliament opted for a republican form of government. From the outset, territorial disputes with Poland (over the Vilnius region and the Suvalkai region) and with Germany (over the Klaipėda region) preoccupied the foreign policy of the new nation. During the interwar period, the constitutional capital was Vilnius, although the city itself was in Poland from 1920 to 1939; Poles and Jews made up a majority of the population of the city, with a small Lithuanian minority of only 0.8 percent.[9] The Lithuanian government was relocated to Kaunas, which officially held the status of temporary capital.

Soviet occupation

In 1940, at the beginning of World War II, the Soviet Union occupied and annexed Lithuania in accordance with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.[10][11] It later came under German occupation, during which around 190,000 or 91 percent of the Lithuanian Jews were killed, resulting in one of the worst death rates of the Holocaust. After the retreat of the Wehrmacht, Lithuania was re-occupied by the Soviet Union in 1944.

During the Nazism and then Soviet occupations between 1940 and 1954, Lithuania lost over 780,000 residents. Of them, an estimated 120,000 to 300,000 were killed or exiled to Siberia by the Soviets, while others chose to emigrate to western countries.[12]

Independence

Fifty years of communist rule ended with the advent of perestroika and glasnost in the late 1980s. Lithuania, led by Sąjūdis, an anti-communist and anti-Soviet independence movement, proclaimed its return to independence on March 11, 1990. Lithuania was the first Soviet republic to do so, though Soviet forces unsuccessfully tried to suppress this secession. The Red Army attacked the Vilnius TV Tower on the night of January 13, 1991, an act that resulted in the death of 13 Lithuanian civilians.[13] The last Red Army troops left Lithuania on August 31, 1993—even earlier than they departed East Germany.

On February 4, 1991, Iceland became the first country to recognize Lithuanian independence. Sweden was the first to open an embassy in the country. The United States had never recognized the Soviet claim to Lithuania, Latvia or Estonia.

Lithuania joined the United Nations on September 17, 1991. On May 31, 2001, Lithuania became the 141st member of the World Trade Organization. Since 1988, Lithuania has sought closer ties with the West, and on January 4, 1994, it became the first of the Baltic states to apply for NATO membership. On March 29, 2004, it became a full and equal NATO member. On May 1, 2004, Lithuania joined the European Union.

Government and politics

Since Lithuania declared independence on March 11, 1990, it has held strong democratic traditions. In the first general elections post-independence on October 25, 1992, 56.75% of the total number of voters supported the new constitution. Drafting the constitution was a long and complicated process. The role of the President fueled the most heated debates. Drawing from the interwar experiences, politicians raised many different proposals ranging from strong parliamentarism to the United States' model of representative democracy. Eventually a compromise semi-presidential system was agreed upon.[14]

The Lithuanian President is the head of state, elected directly for a five-year term; he or she may serve a maximum of two consecutive terms. The post of President is largely ceremonial with oversight of foreign affairs and national security policy. The President is also the commander-in-chief. The President, with the approval of the unicameral Parliament, the Seimas, also appoints the prime minister and on the latter's nomination, appoints the remainder of the cabinet, as well as a number of other top civil servants and the judges for all courts. The judges of the Constitutional Court (Konstitucinis Teismas), who serve for nine year terms, are appointed by the President (three judges), the Chairman of the Seimas (three judges) and the chairman of the Supreme Court (three judges). The Seimas has 141 members who are elected to four-year terms. Seventy one of the members of this legislative body are elected in single constituencies, and the other 70 are elected in a nationwide vote by proportional representation. A party must receive at least 5 percent of the national vote to be represented in the Seimas.

Administration

Lithuania's current administrative division was established in 1994 and modified in 2000 to meet the requirements of the European Union. Lithuania has a three-tier administrative division: the country is divided into ten counties that are further subdivided into 60 municipalities that consist of over 500 elderates.

The counties are ruled by county governors who are appointed by the central government. These officials ensure that the municipalities adhere to the laws of Lithuania and the constitution. County governments oversee local governments and their implementation of the national laws, programs, and policies.[15]

Municipalities are the most important unit. Some municipalities are historically called "district municipalities," and thus are often shortened to "district"; others are called "city municipalities," sometimes shortened to "city." Each municipality has its own elected government. In the past, the election of municipality councils occurred once every three years, but it now takes place every four years. The council elects the mayor of the municipality and other required personnel. The municipality councils also appoint elders to govern the elderates. There is currently a proposal for direct election of mayors and elders that would require an amendment to the constitution.[16]

Elderates are the smallest units and do not play a role in national politics. They were created so that people could receive necessary services close to their homes; for example, in rural areas the elderates register births and deaths. Elderates are most active in the social sector identifying needy individuals or families, and distributing welfare or organizing other forms of relief.

Economy

In 2003, prior to joining the European Union, Lithuania had the highest economic growth rate amongst all candidate and member countries, reaching 8.8 percent in the third quarter. Since 2004, growth in GDP has reflected impressive economic development. (2004 -7.3 percent; 2005 - 7.6 percent; 2006 - 7.4 percent)[17] Most of the trade Lithuania conducts is within the European Union.

It is a member of the World Trade Organization, as well as the European Union. By UN classification, Lithuania is a country with a high average income. The country boasts a well–developed, modern infrastructure of railways, airports and four lane highways. It has almost full employment; the unemployment rate is only 2.9 percent. According to officially published figures, EU membership fueled a booming economy, increased outsourcing into the country, and boosted the tourism sector. The litas, the national currency, has been pegged to the Euro since February 2, 2002 at the rate of EUR 1.00 = LTL 3.4528.[18] Lithuania is expected to switch to the Euro on January 1, 2009.

Like other countries in the region, such as [Estonia]] and Latvia, Lithuania has a flat tax rate rather than a progressive scheme. Lithuanian income levels still lag behind the rest of the older EU members, with per capita GDP in 2007 at 60 percent of the EU average. Lower wages may have led to an increase in emigration to wealthier EU countries in 2004. In 2006, the income tax was reduced to 27 percent and a further reduction to 24 percent is expected in October of 2007. Income tax reduction and 19.1 percent annual wage growth are helping to reverse emigration.[19] The latest official data show emigration in early 2006 to be 30 percent lower than the previous year, with 3,483 people leaving the country.

Demographics

Ethnic diversity

The ethnic population of Lithuanian is 83.6 percent, and speak the Lithuanian language (one of the two surviving members of the Baltic language group), the official language of the state. Several sizable minorities exist, such as Poles (6.7 percent), Russians (6.3 percent), and Belarusians (1.2 percent).[20]

Poles, the largest minority, are concentrated in southeast Lithuania in the Vilnius region. Russians are the second largest minority, concentrated mostly in cities; constituting sizable minorities in Vilnius (14 percent) and Klaipėda (28 percent) and a majority in the town of Visaginas (65 percent). About 3,000 Roma live in Lithuania, mostly in Vilnius, Kaunas, and Panevėžys; their organizations are supported by the National Minority and Emigration Department.

Due to the period of Soviet occupation, most Lithuanians can speak Russian. According to a Eurostat poll, around 80 percent of the Lithuanians can hold a conversation in Russian and almost all are familiar with the most general phrases and expressions. Most Lithuanian schools teach English as a first foreign language, but students may also study German, or, in some schools, French. Students are taught in Russian and Polish in the schools located in areas populated by these minorities.

Religion

The historically predominant religion is Roman Catholicism since the Christianization of Lithuania at the end of fourteenth century and beginning of fifteenth century. Seventy-nine percent of Lithuanians are Roman Catholic.[21] The Roman Catholic Church has historically been influential in the country; priests were actively involved in the resistance against the Communist regime. After independence was regained, priests were again active against socialism and liberalism, especially in ethical questions.

The nationally renowned anti-communist resistance shrine, the Hill of Crosses, upon which thousands of Latin rite crucifixes of all sizes have been placed, is located near the city of Šiauliai. Erecting Latin rite crosses on the hill was forbidden by the Tsarist Russian Orthodox authorities in 1800s. In the twentieth century, the Soviet authorities also forbade such explicit religious symbols. The crosses were removed in 1961 with tractors and bulldozers, but despite Soviet prohibitions, Lithuanian Roman Catholics continued to put small crucifixes and larger crosses on the "Hill of Crosses." Pope John Paul II visited the hill during his visit to Lithuania in 1993, primarily because it was a sign of anti-Communist Catholic resistance, as well as a Roman Catholic religious site. Lithuania was the only majority-Catholic Soviet republic.

The diverse Protestant community (1.9 percent of the total population) is a distant minority. Small Protestant communities are dispersed throughout the northern and western parts of the country. Lithuania was historically positioned between the two German-controlled states of Livonia to the north and the Protestant, formerly monastic, Teutonic State of Prussia to its south. In the sixteenth century, Lutheran Protestantism begin spreading into the country from those regions. Since 1945, Lutheranism has declined in Lithuania.

Various Protestant churches have established missions in Lithuania since independence, including the United Methodists, the Baptist Union, the Mennonites, and World Venture, an evangelical Protestant sect.

The country also has minority communities of Eastern Orthodoxy, mainly among the Russian minority, to which about 4.9 percent of the total population belongs, as well as of Judaism, Islam, and Karaism (an ancient offshoot of Judaism represented by a long-standing community in Trakai), which together make up another 1.6 percent of the population.

Health and welfare

As of 2004, Lithuanian life expectancy at birth was 66 years for males and 78 for females. The infant mortality rate was 8.0 per 1,000 births. The annual population growth rate in 2004 declined by -.5 percent. Less than 2 percent of the population live beneath the poverty line, and the adult literacy rate is 99.6 percent.[22]

Lithuanians have a high suicide rate: 91.7 per 100,000 persons, the highest in the world in 2000, followed by the Russian Federation (82.5), Belarus (73.1), Latvia (68.5), and Ukraine (62.1). This problem has been studied by a number of health organizations.[23]

Culture

Lithuania's cultural history has followed the familiar arc of the Baltic states. Traditional cultures were replaced by the controlling Russian and German aristocracies. Increasing repression coincident with expanding economies and social development led to a rebirth of nationalist feeling in the late nineteenth century. Brief periods of independence in the first half of the twentieth century saw the arts flourishing, only to yield to Soviet censorship. Restoration of independence has brought a new appreciation of the past, and new freedom to explore.

Lithuania's literature dates from the sixteenth century, relatively late for European countries. The earliest extant example of literature dates from the early 1500s and is believed to have been a copy of an earlier document, relating prayers and a protestation of Christian religious belief. Not until the 1800s did Lithuanian literature begin to reflect non-religious ideas; the masterwork Metai (translated as "The Seasons," depicting a year in the life of a village) was published in 1818. The University of Vilnius emerged during this era as a center for scholarship on the history and traditions of Lithuania. Within a few decades, the Tsar banned printing in Lithuanian language. Tracts were smuggled into the country, and together with the repression, served to promote a growing nationalist movement. By the turn of the twentieth century, a virtual renaissance revived the language and literature traditions. Major figures included playwright Aleksandras Guzutis, comic author Vilkutaitis Keturakis, and the renowned poet, Anyksciu Silelis. The Soviet era brought a split: the majority of written works followed the socialist realism model, while a small number of expatriated authors followed traditional literary forms.

Music has played a critical role in Lithuania's identity; an extensive collection of folkloric recordings is preserved in archives, one of the largest such libraries in Europe. National Song Festivals attract tens of thousands of participants. Contemporary Lithuanian music is considered to have begun with the composer Mikalojus Konstantinas Ciurlionis, who worked in the early years of the twentieth century, and spurred a creative awakening in theater, dance, and the representational arts. Currently, Vilnius is known as a center for jazz, with several prominent international jazz festivals hosted there and in other cities.

Traditional arts, chiefly woodworking, have been preserved in nineteenth century manor houses, elaborate house decorations being an important craft illustrated by roof poles, roadside shrines, sculpture, and religious artifacts. Manor houses and other repositories of these examples of traditional arts are protected in the Constitution and legislative acts. Vilnius was unanimously voted "European Capital of Culture 2009," the same year as Lithuania's Millennium Anniversary of its naming.[24]

Notes

- ↑ Population by ethnicity 2009 year. DB1.stat.gov.lt. Statistics Lithuania. Retrieved December 4, 2011.

- ↑ Lithuanian Constitutional Court 1998. Retrieved December 4, 2011.

- ↑ Statistics Lithuania Retrieved December 4, 2011.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Error on call to template:cite web: Parameters url and title must be specified. International Monetary Fund.

- ↑ Baltic Assessment on Climate Change. Climate trends in the Baltic, Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ↑ Sakalauskiene, G.; Ignatavicius, G. February 2003Research Note Effect of drought and fires on the quality of water in Lithuanian rivers, The Smithsonian/NASA Astrophysics Data System. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ↑ (Lithuanian) Tomas Baranauskas. 2001.Lietuvos karalystei—750 (750 years for Kingdom of Lithuania). Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ↑ (English) Daniel Stone. The Polish-Lithuanian state: 1386-1795. (University of Washington Press, 2001), 63

- ↑ (English) L. Donskis. Identity and Freedom: mapping nationalism and social criticism in twentieth-century Lithuania. (Routledge, UK: 2002), 23

- ↑ (English) I. Žiemele. Baltic Yearbook of International Law, 2001. (2002, Vol. 1), 10

- ↑ (English) Karen Dawisha, and Bruce Parrott, (eds). The Consolidation of Democracy in East-Central Europe. (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1997), 293

- ↑ (English) Background Note: Lithuania US Department of State Bureau of Public Affairs, August 2006. Retrieved June 2, 2008.

- ↑ (English) BBC - On This Day. 1991: Bloodshed at Lithuanian TV station, Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ↑ Lina Kulikauskienė. Lietuvos Respublikos Konstitucija (Constitution of Lithuania), (Native History, CD, 2002. ISBN 9986921678)

- ↑ (Lithuanian) Redagavo: Aušrinė Trapinskienė - law database. December 15, 1994. r3/dokpaieska.showdoc_l?p_id=270541 Lietuvos Respublikos apskrities valdymo įstatymas Republic of Lithuania Law on County Governing, Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ↑ (Lithuanian) Justinas Vanagas. September 5, 2005. Seimo prioritetai šią sesiją – tiesioginiai mero rinkimai, gyventojų nuosavybė ir euras - Seimas Priorities this session: direct election of mayors, property of residents, and euro, Delfi.lt. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ↑ (English) Department of Statistics to the Government of the Republic of Lithuania. Change of GDP, 2002-2006, Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ↑ (English) Lietuvos Bankas. Bank of Lithuania National Financial Information, Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ↑ (Lithuanian) Delfi News. Lietuvos gyventojų dar sumažėjo, bet emigravo mažiau. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ↑ (Lithuanian) Department of Statistics to the Government of the Republic of Lithuania. Population by ethnicity, census, Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ↑ (Lithuanian) Department of Statistics to the Government of the Republic of Lithuania. Population by Religious Confession, census, Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ↑ World Health Organization. A guide to statistical information at WHO. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ↑ World Health Organization. Suicide rates. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ↑ The Ministry of Culture.Vilnius, the European Capital of Culture 2009, Retrieved June 25, 2007.

Sources and Further Reading

- Bideleux, Robert. 1998. A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change, 2nd ed. Routledge, [1998] 2007. ISBN 0415366267

- Dawisha, Karen, and Bruce Parrott, (eds). The Consolidation of Democracy in East-Central Europe. Cambridge Univ. Press, 1997. ISBN 0521599385

- Docalavich, Heather. 2006. Lithuania. Philadelphia: Mason Crest Publishers. ISBN 142220054X

- Iwaskiw, Walter R. 1996. Estonia, Latvia & Lithuania: country studies. Area handbook series, 550-113. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 0844408514

- Lerner Publications Company. 1992. Lithuania. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications Co. ISBN 0822528045

- Magocsi, Paul. 1996. History of the Ukraine. University of Washington. ISBN 0295975806

- Magocsi, Paul. Ukraine: an Illustrated History. University of Washington Press, 2007. ISBN 0295987235

- Smith, Hedrick. 1990. The New Russians. New York: Random House. ISBN 0394581903

- Stone, Daniel. The Polish-Lithuanian state: 1386-1795. University of Washington Press, 2001. ISBN 0295980931

- This article contains material from the Library of Congress Country Studies, which are United States government publications in the public domain.

- This article contains material from the CIA World Factbook which, as a U.S. government publication, is in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved November 2, 2022.

- Plenary Sittings. Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.