| Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson | |

|---|---|

| September 29, 1758 – October 21, 1805 | |

Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson, by Lemuel Francis Abbott | |

| Place of birth | |

| Place of death | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | Royal Navy |

| Years of service | 1771 – 1805 |

| Rank | Vice Admiral |

| Battles/wars | Battle of Cape St Vincent Battle of the Nile Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife Battle of Copenhagen Battle of Trafalgar |

| Awards | Several (see below) |

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, Duke of Bronte (September 29, 1758 – October 21, 1805) was a British admiral famous for his participation in the Napoleonic Wars, most notably in the Battle of Trafalgar, where he lost his life. He became the greatest naval hero in the history of the United Kingdom, eclipsing Admiral Robert Blake in fame, and is one of the most famous naval commanders in world history. His biography by the poet Robert Southey appeared in 1813, while the wars were still being fought. His love affair with Emma, Lady Hamilton, the wife of the British ambassador to Naples, is also well-known.

He is honored by the London landmark Nelson's Column, which stands in Trafalgar Square. Nelson's courage, tactical skill and also romantic reputation make him an iconic figure among British heroes. His famous words “England expects that every man will do his duty” continued to serve as inspiration more than a century after his death, helping to galvanize the whole nation during the dark days in 1940 when the British and their colonial allies stood alone against the might of Nazi Germany during World War II.

His naval victories against Napoleon paved the way for Britain's supremacy at sea that would prove vital for the nation's survival during two world wars. He was a true patriot who placed the interests of his country before his own, and remains one of the most famous Englishmen who have ever lived.

Biography

Early life

Nelson was born on September 29, 1758, in a rectory in Burnham Thorpe, Norfolk, England, the sixth of eleven children of The Reverend Edmund Nelson, a Church of England clergyman, and Catherine Nelson. His mother (who died when he was nine), was a grandniece of Sir Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, the de facto first prime minister of the British Parliament.

He learned to sail on Barton Broad on the Norfolk Broads, he was briefly educated at Paston Grammar School, North Walsham and Norwich School and by the time he was twelve, he had enrolled in the Royal Navy. His naval career began on January 1, 1771, when he reported to the third-rate HMS Raisonnable as an ordinary seaman and coxswain. Nelson’s maternal uncle, Captain Maurice Suckling, commanded the vessel. Shortly after reporting aboard, Nelson was appointed a midshipman and began officer training. Ironically, Nelson found that he suffered from chronic seasickness, a complaint that dogged him for the rest of his life.

By 1777 Nelson had risen to the rank of lieutenant, and was assigned to the West Indies, during which time he saw action on the British side of the American Revolutionary War. By the time he was 20, in June 1779, he was made post; the 28-gun frigate HMS Hinchinbroke, newly captured from the French, was his first command as a post-captain.

In 1780 he was involved in an action against the Spanish fortress of San Juan in Nicaragua. Though the expedition was ultimately a major debacle, none of the blame was attributed to Nelson, who was praised for his efforts. He fell seriously ill, probably contracting malaria, and returned to England for more than a year to recover. He eventually returned to active duty and was assigned to HMS Albemarle, in which he continued his efforts against the American rebels until the official end of the war in 1783.

Command

In 1784, Nelson was given command of the frigate Boreas, and assigned to enforce the 1651 Navigation Act in the vicinity of Antigua. This was during the denouement of the American Revolutionary War, and enforcement of the act was problematic—now-foreign American vessels were no longer allowed to trade with British colonies in the Caribbean Sea, an unpopular rule with both the colonies and the Americans. After seizing four American vessels off Nevis, Nelson was sued by the captains of the ships for illegal seizure. As the merchants of Nevis supported them, Nelson was in peril of imprisonment and had to remain sequestered on Boreas for eight months. It took that long for the courts to deny the captains their claims, but in the interim Nelson met Fanny Nesbit, a widow native to Nevis, whom he would marry on March 11, 1787, at the end of his tour of duty in the Caribbean.

Nelson lacked a command from 1789, and lived on half pay for several years (a reasonably common occurrence in the peacetime Royal Navy). However, as the French Revolutionary government began aggressive moves beyond France's borders, he was recalled to service. Given the 64-gun HMS Agamemnon in 1793, he soon started a long series of battles and engagements that would seal his place in history.

He was first assigned to the Mediterranean, based out of the Kingdom of Naples. In 1794 he was wounded in the face by stones and debris thrown up by a close cannon shot during a joint operation at Calvi, Corsica. This cost him the sight in his right eye and half of his right eyebrow. Despite popular legend, there is no evidence that Nelson ever wore an eye patch, though he was known to wear an eyeshade to protect his remaining eye.

In 1796, the commander-in-chief of the fleet in the Mediterranean passed to Sir John Jervis, 1st Earl of St Vincent, who appointed Nelson to be commodore and to exercise independent command over the ships blockading the French coast. Agamemnon, often described as Nelson's favorite ship, was by now worn out and was sent back to England for repairs. Nelson was appointed to the 74-gun HMS Captain.

Admiralty

The year 1797 was a full one for Nelson. On February 14, he was largely responsible for the British victory at the Battle of Cape St Vincent. In the aftermath, Nelson was knighted as a member of the Order of the Bath (hence the postnominal initials "KB"). In April of the same year he was promoted to rear admiral of the blue, the tenth highest rank in the Royal Navy. Later in the year, whilst commanding HMS Theseus, during an unsuccessful expedition to conquer Santa Cruz de Tenerife, he was shot in the right arm with a musketball, fracturing his humerus bone in multiple places. Since medical science of the day counseled amputation for almost all serious limb wounds (to prevent death by gangrene), Nelson lost almost his entire right arm, and was unfit for duty until mid-December. He referred to the stub as "my fin."

This was not his only reverse. In December 1796, on leaving Elba for Gibraltar, Nelson transferred his flag to the frigate Minerve (of French construction, commanded by Captain Cockburn). A Spanish frigate, Santa Sabina, was captured during the passage and Lieutenant Hardy was put in charge of the captured vessel. The following morning, two Spanish ships of the line and one frigate appeared. Nelson decided to flee, leaving Santa Sabina to be recovered by the Spanish and Hardy was captured. The Spanish captain who was on board Minerve was later exchanged for Hardy in Gibraltar.

In 1798, Nelson was once again responsible for a great victory over the French. The Battle of the Nile (also known as the Battle of Aboukir Bay) took place on August 1, 1798 and, as a result, Napoleon's ambition to take the war to the British in India came to an end. The forces Napoleon had brought to Egypt were stranded. Napoleon attempted to march north along the Mediterranean coast but was defeated at the Siege of Acre by Captain (later Admiral) Sir Sidney Smith. Napoleon then left his army and sailed back to France, evading detection by British ships.

For the spectacular victory of the Nile, Nelson was granted the title of Baron Nelson of the Nile. Nelson felt throughout his life that his accomplishments were not fully rewarded by the British government, a fact he ascribed to his humble birth and lack of political connections as compared to Sir John Jervis, or The Duke of Wellington.

Not content to rest on his laurels, he then rescued the Neapolitan royal family from a French invasion in December. During this time, he fell in love with Emma Hamilton; the young wife of the elderly British ambassador to Naples. She became his mistress, returning to England to live openly with him, and eventually they had a daughter, Horatia.

Some have suggested that a head wound he received at Abukir Bay was partially responsible for that conduct, and for the way he conducted the Neapolitan campaign—due simultaneously to his English hatred of Jacobins and his status as a Neapolitan royalist. He was accused of allowing the monarchists to kill prisoners contrary to the laws of war.

In 1799, he was promoted to rear admiral of the red, the eighth-highest rank in the Royal Navy. He was then assigned to the new second-rate HMS Foudroyant. In July, he aided Admiral Ushakov with the reconquest of Naples, and was made duke of Bronte, Sicily, by the Neapolitan king. His personal problems, and upper-level disappointment at his professional conduct caused him to be recalled to England, but public knowledge of his affair with Lady Hamilton eventually induced the Admiralty to send him back to sea, if only to get him away from her.

On January 1, 1801, he was promoted to vice admiral of the blue (the seventh-highest rank). Within a few months he took part in the Battle of Copenhagen (April 2, 1801) which was fought in order to break up the armed neutrality of Denmark, Sweden and Russia. During the battle, Nelson was ordered to cease the battle by his commander Sir Hyde Parker who believed that the Danish fire was too strong. In a famous incident, however, Nelson claimed he could not see the signal flags conveying the order, pointedly raising his telescope to his blind eye. His action was approved in retrospect, and in May, he became commander-in-chief in the Baltic Sea, and was awarded the title of Viscount Nelson by the British crown.

Napoleon was amassing forces to invade England, however, and Nelson was soon placed in charge of defending the English Channel to prevent this. However, on October 22, an armistice was signed between the British and the French, and Nelson—in poor health again—retired to England where he stayed with his friends, Sir William and Lady Hamilton.

The three embarked on a tour of England and Wales, culminating in a stay in Birmingham, during which they visited Matthew Boulton on his sick bed at Soho House, and toured his Soho Manufactory.

The Battle of Trafalgar - Death and burial

The Peace of Amiens was not to last long though, and Nelson soon returned to duty. He was appointed commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean, and assigned to HMS Victory in May 1803. He joined the blockade of Toulon, France, and would not set foot on dry land again for more than two years. Nelson was promoted to vice admiral of the white (the sixth-highest rank) while he was still at sea, on April 23, 1804. The French fleet slipped out of Toulon in early 1805 and headed for the West Indies. A fierce chase failed to turn them up and Nelson's health forced him to retire to Merton in England.

Within two months, his ease ended; on September 13, 1805, he was called upon to oppose the French and Spanish fleets, which had managed to join up and take refuge in the harbor of Cádiz, Spain.

Napoleon had been massing forces once again for the invasion of the British Isles. However, he had already decided that his navy was not adequate to secure the channel for the invasion barges, and had started moving his troops away for a campaign elsewhere in Europe. On the October 19, the French and Spanish fleet left Cádiz, probably because Pierre-Charles Villeneuve, the French commander, had heard that he was to be replaced by another admiral. Nelson, with 27 ships, engaged the 33 opposing ships. On October 21, 1805, Nelson engaged in his final battle, the Battle of Trafalgar.

Nelson's last dispatch, written that day, read:

At daylight saw the Enemy's Combined Fleet from East to E.S.E.; bore away; made the signal for Order of Sailing, and to Prepare for Battle; the Enemy with their heads to the Southward: at seven the Enemy wearing in succession. May the Great God, whom I worship, grant to my Country, and for the benefit of Europe in general, a great and glorious Victory; and may no misconduct in any one tarnish it; and may humanity after Victory be the predominant feature in the British Fleet. For myself, individually, I commit my life to Him who made me, and may his blessing light upon my endeavours for serving my Country faithfully. To Him I resign myself and the just cause which is entrusted to me to defend. Amen. Amen.

As the two fleets moved towards engagement, he then ran up a 31 flag signal to the rest of the fleet which spelled out the famous phrase "England expects that every man will do his duty." The original signal that Nelson wished to make to the fleet was England confides that every man will do his duty (meaning, “is confident that they will”). The signal officer asked Nelson if he could substitute the word 'expects' for 'confides' as 'expects' was included in the code devised by Sir Home Popham, whereas 'confides' would have to be spelled out letter by letter. Nelson agreed, and the signal was run up Victory's mizzenmast.

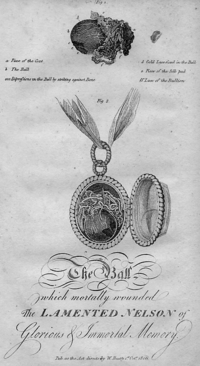

After crippling the French flagship Bucentaure, Victory moved on to the Redoutable. The two ships became entangled, at which point snipers in the fighting tops of Redoutable were able to pour fire down onto the deck of Victory. Nelson was one of those hit: a bullet entered his shoulder, pierced his lung, and came to rest at the base of his spine. Nelson retained consciousness for four hours, but died soon after the battle was concluded with a British victory.

After the battle Victory was then towed to Gibraltar, with Nelson's body on board preserved in a barrel of brandy. Urban legend has it that ironically it was French brandy and had been captured at the battle. Upon the arrival of his body in London, Nelson was given a state funeral (one of only five non-royal Britons to receive the honor—others include Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington and Winston Churchill) and entombment in St. Paul's Cathedral. He was laid to rest in a wooden coffin made from the mast of L'Orient, which had been salvaged after the Battle of the Nile, within a sarcophagus originally carved for Thomas Cardinal Wolsey (when Wolsey fell from favor, it was confiscated by Henry VIII and was still in royal collections in 1805).

Titles

Nelson's titles, as inscribed on his coffin and read out at the funeral by the Garter King at Arms, Sir Isaac Heard, were:

The Most Noble Lord Horatio Nelson, Viscount and Baron Nelson, of the Nile and of Burnham Thorpe in the County of Norfolk, Baron Nelson of the Nile and of Hilborough in the said County, Knight of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath, Vice Admiral of the White Squadron of the Fleet, Commander in Chief of his Majesty's Ships and Vessels in the Mediterranean, Duke of Bronté in the Kingdom of Sicily, Knight Grand Cross of the Sicilian Order of St Ferdinand and of Merit, Member of the Ottoman Order of the Crescent, Knight Grand Commander of the Order of St Joachim.

Legacy

Nelson was noted for his considerable ability to inspire and bring out the best in his men, to the point that it gained a name: "The Nelson Touch." Famous even while alive, after his death he was lionized like almost no other military figure in British history (his only peers are the Duke of Marlborough and Nelson's contemporary, the Duke of Wellington). Most military historians believe Nelson's ability to inspire officers of the highest rank and seamen of the lowest was central to his many victories, as was his unequaled ability to both strategically plan his campaigns and tactically shift his forces in the midst of battle. Certainly, he ranks as one of the greatest field commanders in military history. Many consider him to have been the greatest warrior of the seas.

It must also be said that his "Nelson touch" also worked with non-seamen; he was beloved in England by virtually everyone. Now as then, he is a popular hero, included in the top ten of the 100 Greatest Britons poll sponsored by the BBC and voted for by the public, and commemorated in the extensive Trafalgar 200 celebrations in 2005, including the International Fleet Review. Even today phrases such as "England expects" and "nelson" (meaning "111") remain closely associated with English sporting teams.

Monuments to Nelson

Among the many tributes erected in honor of Nelson, the monumental Nelson's Column and the surrounding Trafalgar Square are notable locations in London to this day. Nelson was buried in St. Paul's Cathedral. The first large monument to Nelson was a 43.5-meter pillar on Glasgow Green erected less than year after his death in 1806. Many subsequent monuments were dedicated throughout the British Empire.

Victory is still kept on active commission in honor of Nelson—it is the flagship of the Second Sea Lord, and is the oldest commissioned ship of the Royal Navy. She can be found in Number 2 Dry Dock of the Royal Navy Museum at the Portsmouth Naval Base, in Portsmouth, England.

Two Royal Navy battleships have been named HMS Nelson in his honor. The Royal Navy celebrates Nelson every October 21 by holding Trafalgar Day dinners and toasting "The Immortal Memory" of Nelson.

The bullet that killed Nelson is permanently on display in the Grand Vestibule of Windsor Castle. The uniform that he wore during the battle, with the fatal bullet hole still visible, can be seen at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. A lock of Nelson's hair was given to the Imperial Japanese Navy from the Royal Navy after the Russo-Japanese War to commemorate the victory at the Battle of Tsushima. It is still on display at Kyouiku Sankoukan, a public museum maintained by the Japan Self-Defense Forces.

Nelson's descendants

Nelson had no legitimate children; his daughter, Horatia, by Lady Hamilton (who died in poverty when their daughter was 13), subsequently married the Rev. Philip Ward and died in 1881. They had nine children.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- Coleman, Terry. The Nelson Touch: The Life and Legend. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 0195173228

- Hayward, Joel S. A. For God and Glory: Lord Nelson and His Way of War. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2003. ISBN 1591143519

- Hibbert, Christopher. Nelson A Personal History. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1994. ISBN 0201624575

- Knight, Rodger. The Pursuit of Victory: The Life and Achievement of Horatio Nelson. New York: Basic Books, 2005. ISBN 046503764X

- Pocock, Tom. Horatio Nelson. London: The Bodley Head, 1987. ISBN 0370311248

- Vincent, Edgar. Nelson: Love & Fame New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003. ISBN 0300097972

- White, Colin. Nelson: The New Letters. Rochester, NY: Boydell Press, 2005. ISBN 1843831309

Further reading

- Lambert, Andrew. Nelson - Britannia's God of War. London: Faber and Faber, 2005. ISBN 0571212220

- Sugden, John. Nelson - A Dream of Glory. London: Jonathan Cape, 2004. ISBN 022406097X

- Worrall, Simon. “Admiral Lord Nelson's Fatal Victory.” National Geographic (October 2005).

External links

All links retrieved January 14, 2018.

- Admiral Lord Nelson and his Navy

- The Death of Lord Nelson by William Beatty from Project Gutenberg

- Lord Nelson's Band of Brothers by W. J. Rayment

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

.jpg/200px-Turner%2C_The_Battle_of_Trafalgar_(1822).jpg)