Macular degeneration

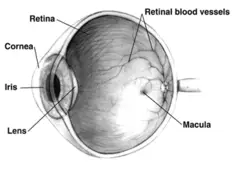

Picture of the back of the eye showing intermediate age-related macular degeneration | |

|---|---|

| ICD-10 | H35.3 |

| ICD-O: | |

| ICD-9 | 362.50 |

| OMIM | {{{OMIM}}} |

| MedlinePlus | 001000 |

| eMedicine | article/1223154 |

| DiseasesDB | 11948 |

Macular degeneration is a medical condition in which there is deterioration in the macula area of the retina, leading to a corresponding loss in central vision, which entails the ability to see fine details, to read, or to recognize faces. The macula area entails the light-sensitive cells at the center of inner lining of the eye (retina). In macular degeneration, this area of the retina may suffer thinning, atrophy, and in some cases, bleeding. This can result in loss of central vision,

Macular degeneration is predominately found in elderly adults and is the leading cause of central vision loss (blindness, although not loss of peripheral vision) in the United States today, for those over the age of fifty years, as well as an important cause of blindness worldwide in the elderly.[1] Other causes of decreased vision in the elderly include presbyopia (age related changes), cataracts, glaucoma, and diabetic retinopathy.

The term macular degeneration generally refers to age-related macular degeneration (AMD or ARMD), while similar changes that affect younger individuals are referred to as some macular dystrophies. Examples of disease causing macular dystrophies in children include Best's disease, Doyne's honeycomb retinal dystrophy, Sorsby's disease, and Stargardt's disease.

As with other disorders, personal responsibility is important. Two of the major risk factors associated with the disease, one's genetic predisposition (genes and family history) and one's age, are factors that one cannot control. However, there are other risk factors that one can control: Obesity, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol. Diet can also be an aid, as vitamin supplements with high doses of antioxidants and zinc have been demonstrated to slow the progression of macular degeneration and foods rich in vitamins are a preventative measure.

Macula

The macula or macula lutea (from Latin macula, "spot" and lutea, "yellow") is an oval yellow spot near the center of the retina of the human eye. It has a diameter of about 1.5 millimeters and is often histologically defined as having two or more layers of ganglion cells. Near its center is the fovea, a small pit that contains the largest concentration of cone cells in the eye and is responsible for central vision.

It is specialized for high acuity vision. Within the macula are the fovea and foveola which contain a high density of cones (photoreceptors with high acuity).

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) begins with characteristic yellow deposits in the macula called drusen, between the retinal pigment epithelium and the underlying choroid. Risks of advanced stages of macular degeneration increase when the drusen are large and numerous and associated with disturbance in the pigmented cell layer under the macula. Advanced AMD, which is responsible for profound vision loss, has two forms: Dry and wet. Dry forms tend to be less severe then wet forms, but both should be taken seriously.

Dry macular degeneration

Central geographic atrophy, the dry form of advanced AMD, progresses much slower then the wet form, and in many cases, the vision loss is less severe. The macula deteriorates over time where the pigmented retinal epithelial (a cell layer housed in the back of the eye) gradually diminishes. This causes the vision loss in the central part of the eye through the photoreceptors (more commonly know as rods and cones). One with AMD may find their vision blurry as well as observing that colors appear gray.[2] Those with the dry version of macular degeneration will find it difficult to adapt to environments with dim lighting and will constantly need bright illumination, especially when doing close work. A sufferer may also notice blurriness of printed words, a decrease in the intensity of colors, and a blind spot in the center of their visual field.[3]

While no treatment is available for this condition, vitamin supplements with high doses of antioxidants (lutein and zeaxanthin) and zinc, have been demonstrated to slow the progression of dry macular degeneration, especially in patients with moderate to severe forms of the disease.[4]

Wet macular degeneration

In the wet form of AMD, also known as neovascular or exudative macular degeneration, abnormal blood vessels grow underneath the retina in the choriocapillaries, through Bruch's membrane, ultimately leading to blood and protein leakage below the macula. Bleeding, leaking, and scarring from these blood vessels eventually leads to irreversible damage of the photoreceptors and rapid vision loss if left untreated. Senile disciform degeneration (also known as Kuhnt-Junius macular degeneration), is a severe wet form that causes hemorrhaging of the blood vessels. The wet form progresses more rapidly than the dry form, and causes more severe damage. About 10 percent of dry forms may develop to wet forms.

A patient with this form of AMD, will note that straight lines will appear wavy and a central blind spot will form. In addition, he or she may see objects appearing smaller or farther away as compared to reality. As with the dry form, patients will also develop a central blurry spot.

Until recently, no effective treatments were known for wet macular degeneration. However, new drugs, called anti-angiogenics or anti-VEGF (anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) agents, when injected directly into the vitreous humor of the eye using a small, painless needle, can cause regression of the abnormal blood vessels and improvement of vision.[5] The injections frequently have to be repeated on a monthly or bi-monthly basis. Examples of these agents include Lucentis and Avastin, both of which are FDA approved. Other therapies include thermal laser photocoagulation and photodynamic therapy depending on extent and location of lesion.

Risk factors

- Aging: According to researches at the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, macular degeneration is the leading cause of severe vision loss in people age 60 and older.

- Family history: If a patient’s family has a history of any form of AMD, he or she is more likely to develop this disease than those without a history.

- Macular degeneration gene: The genes for the complement system (a system in the body responsible for blood coagulation) proteins factor H (CFH) and factor B (CFB) have been determined to be strongly associated with a person's risk for developing macular degeneration. CFH is involved in inhibiting the inflammatory response mediated through C3b (and the alternative pathway of complement) both by acting as a cofactor for cleavage of C3b to its inactive form, C3bi, and by weakening the active complex that forms between C3b and factor B. C-reactive protein and polyanionic surface markers such as glycosaminoglycans normally enhance the ability of factor H to inhibit complement. But the mutation in CFH (Tyr402His) reduces the affinity of CFH for CRP, and probably also alters the ability of factor H to recognize specific glycosaminoglycans. This change results in reduced ability of CFH to regulate complement on critical surfaces such as the specialized membrane at the back of the eye, thus leading to increased inflammatory response within the macula.[6]

- Hypertension and cardiovascular status: High blood pressure, high cholesterol, and obesity are a few other risk factors for macular degeneration.[7]

- Oxidative stress: It has been proposed that age related accumulation of low molecular weight, phototoxic, pro-oxidant melanin oligomers within lysosomes in the retinal pigment epithelium may be partly responsible for decreasing the digestive rate of photoreceptor outer rod segments (POS) by the RPE. A decrease in the digestive rate of POS has been shown to be associated with lipofuscin formation—a classic sign associated with macular degeneration.[8]

- Sex: Women are at a much higher risk of developing macular degeneration than men, especially since they tend to live longer.

- Race: Macular degeneration is more likely to be found in whites than in any other race.[9]

- Exposure to sunlight (especially blue light): Exposure to sunlight may also contribute to the development of macular degeneration. This is because the eye’s retina is more sensitive to ultraviolet light (UV).

Signs

Macular degeneration destroys one's sharp, central vision. Some common signs of macular degeneration include the need for more light when looking at anything close up. Fine typeface and other details will become more difficult to read, as well as text on signs. In addition, a sufferer will see gray or blank spots in the center of their field of vision, adding to visible difficulties.

Other signs include the following:

- Drusen—characterized by yellow deposits in the macula

- Pigmentary alterations

- Exudative changes: Hemorrhages in the eye, hard exudates, subretinal/sub-RPE/intraretinal fluid

- Atrophy: Incipient and geographic

- Visual acuity drastically decreasing (two levels or more) ex: 20/20 to 20/80.

Symptoms

- Blurred vision: Those with nonexudative macular degeneration may notice a gradual loss of central vision, whereas those with exudative macular degeneration often notice a rapid onset of vision loss.

- Central scotomas: There may be shadows or missing areas of vision.

- Distorted vision (such as metamorphopsia): A grid of straight lines appears wavy and parts of the grid may appear blank. Patients often first notice this when looking at mini-blinds in their home.

- Trouble discerning colors: This may specifically involve trouble discerning dark ones from dark ones and light ones from light ones.

- Slow recovery of visual function after exposure to bright light

"Vision loss" or "blindness" in macular degeneration refers to the loss of "central vision" only. The peripheral vision is not affected. Blindness in macular degeneration does not mean "inability to see light" and even with far advanced macular degeneration, the peripheral retina allows for useful vision. The loss of central vision affects visual functioning, such as the ability to read. In some cases, the disease only affects one eye at a time, making it more difficult to identify macular degeneration.

Similar symptoms with a very different etiology and different treatment can be caused by epiretinal membrane or macular puckeror leaking blood vessels in the eye.

Other forms

Other less common forms of macular degeneration include:

- Cystoid macular degeneration. This is loss of vision in the macula due to fluid-filled areas (cysts) in the macular region. This may be a result of other disorders, such as aging, inflammation, or high myopia.

- Diabetic macular degeneration. This is deterioration of the macula due to diabetes.

- Juvenile macular degeneration (JMD). This is a group of inherited disorders affecting children and younger adults.

- Cystoid macular degeneration. This is the development of fluid-filled cysts (sacs) in the macular region, associated with aging, inflammation, or severe myopia.

- Retinal pigment epithelial detachment. This is a rare form of wet MD in which fluid leakage from the choroid causes the detachment or disappearance of the pigmented retinal epithelium.

Diagnosis

Although this vision loss is irreversible, early detection may slow the progression of dry to wet AMD. Fluorescein angiography allows for the identification and localization of abnormal vascular processes. Optical coherence tomography is now used by most ophthalmologists in the diagnosis and the follow up evaluation of the response to treatment by using either Avastin or Lucentis, which are injected into the eye at various intervals.

The Amsler Grid Test is one of the simplest and most effective methods for patients to monitor the health of the macula. The Amsler Grid is essentially a pattern of intersecting lines (identical to graph paper) with a black dot in the middle. The central black dot is used for fixation (a place for the eye to stare at). With normal vision, all lines surrounding the black dot will look straight and evenly spaced with no missing or odd looking areas when fixating on the grid's central black dot. When there is disease affecting the macula, as in macular degeneration, the lines can look bent, distorted and/or missing.

Other forms of diagnosis include a dilated eye exam, where drops are used to dilate the pupils and the retina can be observed.

Prevention

The Age-Related Eye Disease Study showed that a combination of high-dose beta-carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, and zinc can reduce the risk of developing advanced AMD by about 25 percent in those patients who have earlier but significant forms of the disease. This is the only proven intervention to decrease the risk of advanced AMD at this time.

Anecortave acetate, (Retanne), is an anti-angiogenic drug that is given as an injection behind the eye (avoiding an injection directly into the eye) that is currently being studied as a potential way of reducing the risk of neovascular (or wet) AMD in high-risk patients.

Intravitreal injection of Avastin (bevacizumab) can also improve vision and slow down the macular degeneration. Avastin is an immunoligic drug that prevents neovascularization. Hence it may also be effective in diabetic retinopathy. Avastin was initially used for the treatment of colorectal cancer.

Foods containing antioxidants with vitamins A, C and E can also help prevent macular degeneration. Foods considered good sources of these nutrients also include kale, turnip, greens, collard greens, romaine lettuce, broccoli, zucchini, corn, garden peas, and Brussels sprouts.

Impact

Macular degeneration, in its advanced forms, can result in legal blindness, resulting in a loss of driving privileges and an inability to read all but very large type. Perhaps the most grievous loss is the inability to see faces clearly or at all.

Some of these losses can be offset by the use of adaptive devices. A closed-circuit television reader can make reading possible, and specialized screen-reading computer software, for example, JAWS for Windows, can give the blind person access to word processing, spreadsheet, financial, and e-mail access.

Notes

- ↑ P. T. de Jong, "Age-related macular degeneration," N Engl J Med. 355(2006)(14): 1474-1485.

- ↑ Kierstan Boyd, Macular Degeneration Symptoms Eye Health, American Academy of Ophthalmology. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

- ↑ Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, Dry Macular Degeneration: Symptoms and causes Retrieved September 22, 2016.

- ↑ W. G. Christen, R. J. Glynn, and C. H. Hennekens, "Antioxidants and age-related eye disease. Current and future perspectives," Ann Epidemiol 6(1996): 60.

- ↑ P. van Wijngaarden, D. J. Coster, and K. A. Williams, Inhibitors of ocular neovascularization: promises and potential problems. JAMA 293(2005): 1509.

- ↑ Z. Yang, N. J. Camp, H. Sun, Z. Tong, D. Gibbs, D. J. Cameron, H. Chen, Y. Zhao, E. Pearson, X. Li, J. Chien, A. Dewan, J. Harmon, P. S. Bernstein, V. Shridhar, N. A. Zabriskie, J. Hoh, K. Howes, and K. Zhang, "A variant of the HTRA1 gene increases susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration," Science. 314(2006)(5801): 992-993.

- ↑ J. P. SanGiovanni, E. Y. Chew, T. E. Clemons, M. D. Davis, F. L. Ferris, G. R. Gensler, N. Kurinij, A. S. Lindblad, R. C. Milton, J. M. Seddon, and R. D. Sperduto, The relationship of dietary lipid intake and age-related macular degeneration in a case-control study, Archives of Ophthamology 125(2007): 671-679. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

- ↑ R. Sarangarajan, and S. P. Apte, "Melanin aggregation and polymerization: possible implications in age related macular degeneration," Ophthalmic Research 37(2005): 136-141.

- ↑ Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group, "Risk factors associated with age-related macular degeneration. A case-control study in the age-related eye disease study: Age-Related Eye Disease Study Report Number 3." Ophthalmology. 107(2000)(12): 2224-2232.

External links

All links retrieved November 5, 2022.

- Age-related Macular Degeneration Resource Guide from the National Eye Institute (NEI).

- Results from NEI's Age Related Eye Disease Study showed that high levels of antioxidants and zinc significantly reduce the risk of advanced AMD and its associated vision loss.

- An open-access eBook on Macular Degeneration: Protect Your Sight—How to Save your Vision in the Epidemic of Age-Related Macular Degeneration by James C. Folk, MD and Mark E. Wilkinson, OD—Published March 2006.

| Pathology of the eye (primarily H00-H59) | |

|---|---|

| Eyelid, lacrimal system and orbit | Stye - Chalazion - Blepharitis - Entropion - Ectropion - Lagophthalmos - Blepharochalasis - Ptosis - Xanthelasma - Trichiasis - Dacryoadenitis - Epiphora - Exophthalmos - Enophthalmos |

| Conjunctiva | Conjunctivitis - Pterygium - Subconjunctival hemorrhage |

| Sclera and cornea | Scleritis - Keratitis - Corneal ulcer - Snow blindness - Thygeson's superficial punctate keratopathy - Fuchs' dystrophy - Keratoconus - Keratoconjunctivitis sicca - Arc eye - Keratoconjunctivitis - Corneal neovascularization - Kayser-Fleischer ring - Arcus senilis |

| Iris and ciliary body | Iritis - Uveitis - Iridocyclitis - Hyphema - Persistent pupillary membrane |

| Lens | Cataract - Aphakia |

| Choroid and retina | Retinal detachment - Retinoschisis - Hypertensive retinopathy - Diabetic retinopathy - Retinopathy - Retinopathy of prematurity - Macular degeneration - Retinitis pigmentosa - Macular edema - Epiretinal membrane - Macular pucker |

| Ocular muscles, binocular movement, accommodation and refraction | Strabismus - Ophthalmoparesis - Progressive external ophthalmoplegia - Esotropia - Exotropia - Refractive error - Hyperopia - Myopia - Astigmatism - Anisometropia - Presbyopia - Fourth nerve palsy - Sixth nerve palsy - Kearns-Sayre syndrome - Esophoria - Exophoria - Duane syndrome - Convergence insufficiency - Internuclear ophthalmoplegia - Aniseikonia |

| Visual disturbances and blindness | Amblyopia - Leber's congenital amaurosis - Subjective (Asthenopia, Hemeralopia, Photophobia, Scintillating scotoma) - Diplopia - Scotoma - Anopsia (Binasal hemianopsia, Bitemporal hemianopsia, Homonymous hemianopsia, Quadrantanopia) - Color blindness (Achromatopsia) - Nyctalopia - Blindness/Low vision |

| Commonly associated infectious diseases | Trachoma - Onchocerciasis |

| Other | Glaucoma - Floater - Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy - Red eye - Argyll Robertson pupil - Keratomycosis - Xerophthalmia - Aniridia |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.