Mandrake (plant)

| Mandrake | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

Mandragora autumnalis |

Mandrake is the common name for any of the herbaceous, perennial plants comprising the genus Mandragora of the nightshade family Solanacea, and in particular Mandragora officinarum, whose long, fleshy, often forked root can roughly resemble the human body and has long had medicinal, mystical, and magical properties associated with it. The term mandrake also is commonly used for the roots of these plants, which contain poisonous alkaloids and have been used medicinally for their anodyne (relieves pain through external application) and soporific properties, but also can lead to delirium and hallucinations. Mandragora species are native to the Mediterranean and the Himalayas.

References to the importance of mandrake in human culture trace back as far as the book of Genesis and in ancient Greek and Roman societies. With roots that sometimes contain bifurcations causing them to resemble human figures, mandrakes long have been associated with mystical properties and with magic rituals. Even today, in neopagan religions such as Wicca and Germanic revivalism religions such as Odinism, the mandrake continues to play a role.

Overview and description

The genus Madragora belong to the nightshade or potato family Solanaceae, a taxon of flowering plants in the Solanales order. Members of this family are characterized by five-petaled flowers, and alternate or alternate to opposite leaves. This family also is are known for possessing a diverse range of alkaloids, which for humans can be toxic, beneficial, or both. For the plants, they reduce the tendency of animals to eat the plants.

Mandrakes, comprising genus Madragora, are herbaceous, perennial plants native to areas of the Mediterranean and the Himalayas.

The most well known mandrake is Mandragora officinarum. This plant has a parsley-shaped root that is often branched. This root gives off at the surface of the ground a rosette of ovate-oblong to ovate, wrinkled, crisp, sinuate-dentate to entire leaves, 6 to 16 inches long, somewhat resembling those of the tobacco plant. Springing from the neck are a number of one-flowered nodding peduncles, bearing whitish-green flowers, nearly two inches broad, which produce globular, succulent, orange to red berries, resembling small tomatoes, which ripen in late spring. The plant grows grow natively in southern and central Europe and in lands around the Mediterranean Sea, as well as on Corsica. This plant is called by the Arabs luffâh, or beid el-jinn ("djinn's eggs").

Tropine alkaloids

One of the most important groups of alkaloid compounds found in members of the Mandragora genus are tropane alkaloids, which also are found in the Solanaceae genera Atropa (the belladonna genus), Datura, and Brugmansia, as well as many others in the Solanaceae family. Chemically, the molecules of these compounds have a characteristic bicyclic structure and include atropine, scopolamine, and hyoscyamine. Pharmacologically, they are the most powerful known anticholinergics in existence, meaning they inhibit the neurological signals transmitted by the endogenous neurotransmitter, acetylcholine. Symptoms of overdose may include mouth dryness, dilated pupils, ataxia, urinary retention, hallucinations, convulsions, coma, and death.

All parts of the mandrake plant are poisonous. The fruit likewise causes poisoning in cattle. The Arab name mandragora means "hurtful to cattle" (Blakemore and Jennett 2001).

Medicinal uses

Mandrake's medicinal uses date back to ancient times, with references to it being used as a cure to sterility in Genesis 3:14-16 and in the time of Pliny (23-79 C.E.) it was being given to patients before surgery by having them chew of pieces of root (Blakemore and Jennett 2001). The root can be very toxic, but also is used as an adnodyne to relieve and soothe pain (by lessening the sensitivity of the brain or nervous system) and for its soporific properties (inducing sleep). It historically also has been used as emetic (induces vomiting) and purgative (induce bowel movements) (Blakemore and Jennett 2001).

From ancient times, the root was promoted for such uses as an aphrodisiac and for fertility. Dioscorides, a Greek physician of the first century, described how a wine made from mandrake produces anesthesia, noting it can be used for those who cannot sleep, or have severe pain, or are being cauterized or cut, with the use of it resulting in that they will not feel pain (Peduto 2001).

Cultural references, myths, and magic

Hebrew Bible

In Genesis 30, Reuben, the eldest son of Jacob and Leah, finds mandrakes in the field. Rachel, Jacob's second wife, the sister of Leah, is desirous of the mandrakes and she barters with her sister for them. The trade offered by Rachel is for Leah to spend the next night in Jacob's bed. Soon after this Leah, who previously had had four sons but had ceased to become pregnant for a long while, then became pregnant once more and gave birth to a son. There are classical Jewish commentaries which suggest that mandrakes help barren women to conceive a child.

Mandrake in Hebrew is דודאים (dûdã'im), meaning “love plant.” Most interpreters hold Mandragora officinarum to be the plant intended in Genesis 30:14 ("love plant") and Song of Songs 7:13 ("the mandrakes send out their fragrance"). A number of other plants have been suggested such as bramble-berries, Zizyphus Lotus, the sidr of the Arabs, the banana, the lily, the citron, and the fig.

Myths and magic

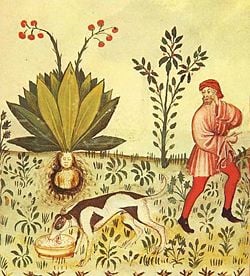

The mandrake has been a source of considerable superstition, with the mystical properties likely attributed because the root may resemble a human form, with arm and leg appendages.

According to the legend, when the root is dug up it lets out a horrible shriek that kills all who hear it or drives them mad. Literature includes complex directions for harvesting a mandrake root in relative safety. For example, Josephus (c. 37 C.E. Jerusalem – c. 100) gives the following directions for pulling it up:

A furrow must be dug around the root until its lower part is exposed, then a dog is tied to it, after which the person tying the dog must get away. The dog then endeavors to follow him, and so easily pulls up the root, but dies suddenly instead of his master. After this the root can be handled without fear. (V.A. Peduto, translating Greek physician Dioscorides)

This superstition, with the plant letting out a deadly scream and using a dog to remove the mandrake, is well known in the literature. Other superstitions quoted by Theophrastus and Pliny the Elder, noting the dire consequences of uprooting a mandrake, stated that these could be avodied by making circles around the plant on the ground with a sword and then facing west while digging (Peduto 2001).

Mandrake has been used for expelling demons and was an important ingredient for lunar rituals, being sued to produce moon water. The moon water was produced by placing small pieces of root in a chalice of water and exposing it to moonlight every night until the full moon (Blakemore and Jennett 2001).

Some of the magical qualities of mandrake can be found in this passage from Chapter XVI, "Witchcraft and Spells" of Arthur Edward Waite's edited translation of Eliphas Levi's Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie (1896):

…we will add a few words about mandragores (mandrakes) and androids, which several writers on magic confound with the waxen image; serving the purposes of bewitchment. The natural mandragore is a filamentous root which, more or less, presents as a whole either the figure of a man, or that of the virile members. It is slightly narcotic, and an aphrodisiacal virtue was ascribed to it by the ancients, who represented it as being sought by Thessalian sorcerers for the composition of philtres. Is this root the umbilical vestige of our terrestrial origin? We dare not seriously affirm it, but all the same it is certain that man came out of the slime of the earth, and his first appearance must have been in the form of a rough sketch. The analogies of nature make this notion necessarily admissible, at least as a possibility. The first men were, in this case, a family of gigantic, sensitive mandragores, animated by the sun, who rooted themselves up from the earth; this assumption not only does not exclude, but, on the contrary, positively supposes, creative will and the providential co-operation of a first cause, which we have reason to call God.

Some alchemists, impressed by this idea, speculated on the culture of the mandragore, and experimented in the artificial reproduction of a soil sufficiently fruitful and a sun sufficiently active to humanise the said root, and thus create men without the concurrence of the female. (See: Homunculus) Others, who regarded humanity as the synthesis of animals, despaired about vitalising the mandragore, but they crossed monstrous pairs and projected human seed into animal earth, only for the production of shameful crimes and barren deformities. The third method of making the android was by galvanic machinery. One of these almost intelligent automata was attributed to Albertus Magnus, and it is said that St Thomas (Thomas Aquinas) destroyed it with one blow from a stick because he was perplexed by its answers. This story is an allegory; the android was primitive scholasticism, which was broken by the Summa of St Thomas, the daring innovator who first substituted the absolute law of reason for arbitrary divinity, by formulating that axiom which we cannot repeat too often, since it comes from such a master: " A thing is not just because God wills it, but God wills it because it is just.

The real and serious android of the ancients was a secret which they kept hidden from all eyes, and Mesmer was the first who dared to divulge it; it was the extension of the will of the magus into another body, organised and served by an elementary spirit; in more modern and intelligible terms, it was a magnetic subject.

It was a common belief in some countries that a mandrake would grow where the seed of a hanged man dripped on to the earth; this would appear to be the reason for the methods employed by the alchemists who "projected human seed into animal earth." In Germany, the plant is known as the Alraune: the novel Alraune by Hanns Heinz Ewers is based around a soulless woman conceived from a hanged man's seed, the title referring to this myth of the mandrake's origins.

The following is taken from "Paul Christian's "The History and Practice of Magic:

Would you like to make a Mandragora, as powerful as the homunculus (little man in a bottle) so praised by Paracelsus? Then find a root of the plant called bryony. Take it out of the ground on a Monday (the day of the moon), a little time after the vernal equinox. Cut off the ends of the root and bury it at night in some country churchyard in a dead man's grave. For thirty days water it with cow's milk in which three bats have been drowned. When the thirty-first day arrives, take out the root in the middle of the night and dry it in an oven heated with branches of verbena; then wrap it up in a piece of a dead man's winding-sheet and carry it with you everywhere.

Literature

There are innumerable literary references to the mandrake. The following are some of the more well-known examples.

- In the Bible

In Genesis 30:14, Leah gives Rachel mandrakes in exchange for a night of sleeping with their husband.

- During wheat harvest, Reuben went out into the fields

- and found some mandrake plants,

- which he brought to his mother Leah.

- Rachel said to Leah, "Please

- give me some of your son's mandrakes."

Song of Songs 7:13 KJV

- "The mandrakes send out their fragrance,

- and at our door is every delicacy,

- both new and old,

- that I have stored up for you, my lover."

- Machiavelli wrote a play Mandragola (The Mandrake) in which the plot revolves around the use of a mandrake potion as a ploy to bed a woman.

- Shakespeare refers four times to mandrake and twice under the name of mandragora.

- "…Not poppy, nor mandragora,

- Nor all the drowsy syrups of the world,

- Shall ever medicine thee to that sweet sleep

- Which thou owedst yesterday."

- Shakespeare: Othello III.iii

Aton Re Luven Angel 4 -----

- "Give me to drink mandragora…

- That I might sleep out this great gap of time

- My Antony is away."

- Shakespeare: Antony and Cleopatra I.v

- "Shrieks like mandrakes' torn out of the earth."

- Shakespeare: Romeo and Juliet IV.iii

- "Would curses kill, as doth the mandrake's groan"

- King Henry IV part II III.ii

- Thomas Lovell Beddoes uses the name of mandrake for a character in his play, Death's Jest Book.

- John Webster in The Duchess of Malfi:

- Ferdinand "I have this night digged up a mandrake…"

- John Donne's song:

- "Go and catch a falling star

- Get with child a mandrake root

- Tell me where all past years are,

- Or who cleft the devil's foot…"

- Ezra Pound used it as metaphor in his poem "Portrait d'une femme":

- "You are a person of some interest, one comes to you

- And takes strange gain away: […]

- Pregnant with mandrakes, or with something else

- That might prove useful and yet never proves, […]"

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Blakemore, C., and S. Jennett. 2001. The Oxford Companion to the Body. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 019852403X.

- Levi, Eliphas. Dogma et Rituel de la Haute Magie, Translated by A. E. Waite. (London, England: Rider & Company, 1896). [1].scribd.com. Retrieved November 24, 2008.

- Peduto, V. A. 2001. The mandrake root and the Viennese Dioscorides. Minerva-Anestesiol 67(10): 751-766. Retrieved November 14, 2008.

- Pitois, C. and Paul Christian. (1963) 1972. The History and Practice of Magic, edited by Ross Nichols; James Kirkup and Julian Shaw (Translators). New York: Citadel Press. ISBN 080650126X.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.