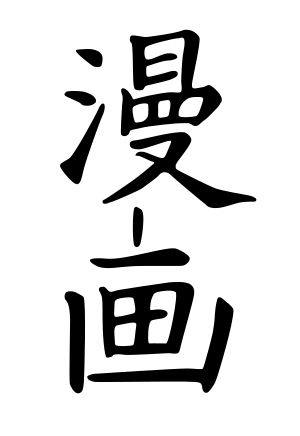

Manga

Manga (in kanji 漫画; in hiragana まんが; in katakana マンガ), pronounced /ˈmɑŋgə/, is the Japanese word for comics (sometimes called komikku コミック) and print cartoons. In their modern form, manga date from shortly after World War II but have a long, complex background in earlier Japanese art.

In Japan, manga are widely read by people of all ages, and include a broad range of subjects including action-adventure, romance, sports and games, historical drama, comedy, science fiction and fantasy, mystery, horror, sexuality, and business and commerce. Since the 1950s, manga have steadily become a major part of the Japanese publishing industry,representing total sales of 481 billion yen in Japan in 2006 (approximately US$4.4 billion). Manga have also become increasingly popular worldwide. In 2006, the United States manga market was $175–200 million. Manga are typically printed in black-and-white, although some full-color manga exist. In Japan, manga are usually serialized in telephone book-size manga magazines, often containing many stories, each presented in a single episode to be continued in the next issue. If the series is successful, collected chapters may be republished in paperback books called tankōbon and in collectible special editions. A manga artist (mangaka in Japanese) typically works with a few assistants in a small studio and is associated with a creative editor from a commercial publishing company. If a manga series is popular enough, it may be animated after or even during its run, and serialized on television. Sometimes manga are drawn centering on previously existing live-action or animated films such as Star Wars.

When used outside Japan, the term “manga” refers specifically to comics originally published in Japan. In recent decades the manga industry has expanded worldwide through distribution companies that license and reprint manga in other languages. The largest overseas markets for Japanese comic magazines have been in Asian countries such as Thailand, Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong, Indonesia, and Peoples Republic of China, but since the mid-1990s it has also become popular in the West. Japanese manga has had an increasing influence on both the styles and aesthetics of comics and on the marketing of comics internationally. It has also played an important role in disseminating Japanese culture abroad, attracting young people from many countries to study Japanese and visit Japan as tourists.

Etymology

"Manga," literally translated, means "whimsical pictures." The word first came into common usage in the late eighteenth century with the publication of such works as the picture book "Shiji no yukikai" (1798) by Santō Kyōden (山東京伝, 1761 – 1816) and in the early nineteenth century with such works as Aikawa Minwa's "Manga hyakujo" (1814) and the celebrated Hokusai manga containing assorted drawings from the sketchbook of the famous ukiyo-e artist Hokusai (1760 – 1849).[1] The first to use the word "manga" in its modern sense was Rakuten Kitazawa (北澤 楽天, 1876 – 1955), the first professional cartoonist in Japan and the mentor of many younger mangaka and animators.[2]

History and characteristics

Historians and writers on manga history differ over the extent to which the development of manga in Japan was influenced by cultural and historical events following World War II. Some emphasize the importance of exposure to U.S. cultural influences, including U.S. comics brought to Japan by the GIs and images and themes from U.S. television, film, and cartoons (especially Disney) during the U.S. Occupation of Japan (1945–1952). [3] Others such as Frederik L. Schodt,[4][5] Kinko Ito,[6] and Adam L. Kern[7] consider manga to be a modern continuation of pre-War, Meiji, and pre-Meiji Japanese culture and aesthetic traditions.

The roots of manga can be traced to early magazines for children which appeared in the late nineteenth century, as part of the Meiji-era effort to encourage literacy. Shôjo kai ("Girls' World"), first published in 1902, began the segregation of children's magazines along gender lines. These magazines typically included several pages of cartoons along with serialized adventure novels.[8]

Modern manga originated during the Occupation (1945–1952) and post-Occupation years (1952–early 1960s), when a previously militaristic and ultranationalist Japan was rebuilding its political and economic infrastructure.[4] After the war, publishers in Osaka began to produce inexpensive books of manga on cheap, recycled pulp paper, known as akahon ("red books") because of the red ink that was used along with black ink for a two-tone effect. Tezuka Osamu (|手塚 治虫, 1928– 1989), creator of Astro Boy, used these relatively thick (often 100 pages or more) books for a new genre he called "story manga."

Osamu Tezuka and Machiko Hasegawa (長谷川町子, 1920 – 1992), creator of Sazae-san, were stylistic innovators who shaped the development of modern manga. Tezuka’s Astro Boy quickly achieved popularity in Japan and abroad,[9][10] Tezuka's "cinematographic" technique utilized panels revealing details of the action resembling slow motion, and rapid zooms from distance to close-up shots. This kind of visual dynamism was widely adopted by later manga artists.[4] Hasegawa's focus on daily family life and the experiences of women came to characterize later shōjo manga.[11][12] Her comic strip was turned into a dramatic radio series in 1955 and a weekly animated television series in 1969, which was still running in 2022.

Between 1950 and 1969, as the two primary genres of manga, shōnen manga aimed at boys and shōjo manga aimed at girls[4][13] solidified, increasingly large audiences for manga emerged in Japan.

In 1969, a group of female manga artists later called the Year 24 Group (also known as Magnificent 24s) made their shōjo manga debut (“Year 24” comes from the Japanese calendar year for 1949, when many of these artists were born).[11][14] The group, which marked the first major entry of women artists into manga, included Hagio Moto, Riyoko Ikeda, Yumiko Oshima, Keiko Takemiya, and Ryoko Yamagishi[11] [4] After 1969, shōjo manga was drawn primarily by women artists for an audience of girls and young women. [8] In the following decades, shōjo manga continued to develop stylistically while evolving different but overlapping subgenres.[15] Major subgenres include romance, superheroines, and "Ladies Comics" (in Japanese, redisu レディース, redikomi レディコミ, and josei 女性).[11][5]

In modern shōjo manga romance, love is a major theme set into emotionally intense narratives of self-realization.[16] Shōjo manga such as Naoko Takeuchi's Pretty Soldier Sailor Moon, which became internationally popular in both manga and anime formats, feature superheroines on a quest. [17][5] The theme of teams (sentai) of girls working together is also extensively developed in shōjo manga.[18]

Boys and young men were among the earliest readers of manga after World War II.[5] From the 1950s, shōnen manga focused on subjects thought to interest the archetypal boy, such as robots, space travel, and heroic action-adventure.[11] Popular themes include science fiction, technology, sports, and supernatural settings. Manga with solitary costumed superheroes like Superman, Batman, and Spider-Man generally did not become as popular.[4]

Manga for male readers can be classified by the age of its intended audience: boys up to 18 years old (shōnen manga) and young men 18- to 30-years old (seinen manga),[19] as well as by content, including action-adventure often involving male heroes, slapstick humor, themes of honor, and sometimes explicit sexuality.[20] The Japanese use different kanji for two closely allied meanings of "seinen"—青年 for "youth, young man" and 成年 for "adult, majority"—the second referring to sexually overt manga aimed at grown men and also called seijin ("adult," 成人) manga.[5] Shōnen, seinen, and seijin manga share many features in common.

The role of girls and women in manga for male readers has evolved considerably over time to include those featuring single pretty girls (bishōjo)[21] Belldandy from Oh My Goddess!),[22] stories where the hero is surrounded by such girls and women (Negima[23] and Hanaukyo Maid Team),[24] or groups of heavily armed female warriors (sentō bishōjo)[25]

Gekiga is an emotionally dark, often starkly realistic, and sometimes violent style of drawing that depicts the sordid aspects of life, often drawn in a coarse manner.[5] Gekiga such as Sampei Shirato's 1959-1962 Chronicles of a Ninja's Military Accomplishments (Ninja Bugeichō) arose in the late 1950s and 1960s partly from left-wing student and working class political activism[5][11] and partly from the aesthetic dissatisfaction of young manga artists like Yoshihiro Tatsumi with existing manga.[14]

Publications

In 2007, sales of manga in Japan were 406.7 billion yen (US$3.71 billion), a 20 percent decline from 1996, when total sales reached 584.7 billion yen. During that time the circulation of manga magazines dropped by half. Entertainment executives were concerned because the manga industry is one of the foundations of Japanese entertainment culture. The decline is attributed to a decreasing population of young adults in Japan, and to a gradual shift away from printed books and towards digital entertainment such as video games, computer and cell phones.[26] Many anime movies and television series have been adapted from popular manga, and they are also licensed for use in merchandise such as clothing, accessories, toys, stationery products and digital games.

Typically, manga are first published in phone-book-sized weekly or monthly anthology manga magazines (such as Afternoon, Shonen Jump, or Hana to Yume). These anthologies often have hundreds of pages and dozens of individual storylines by multiple authors. They are printed on very cheap newsprint and are considered disposable. When a series has been running for a while, the chapters are usually collected and printed in dedicated paperback-sized volumes on higher quality paper, called tankōbon. These are similar to U.S. trade paperbacks or graphic novels, and are popular with readers who want to "catch up" with a series so they can follow it in the magazines, or who find the cost of the weeklies or monthlies prohibitive. Japanese people frequently refer to manga tankōbon as komikkusu (コミックス), from the English word "comics."

Old manga have also been reprinted using somewhat lesser quality paper and sold for 100 yen (about $1 U.S. dollar) each to compete with the used book market.

In Japan, where coffee shops are popular, manga cafés, or manga kissa (kissa is an abbreviation of kissaten) stock hundreds of manga that their customers can read while they linger over coffee.

Aizōban and kanzenban

The most popular manga (such as Dragon Ball), are sometimes released in aizōban (愛蔵版), a more expensive collector's edition with extra features such as unique covers created specifically for the edition, a cover made of special paper, higher quality paper, and a slipcase. Aizōban are typically printed in a limited run, increasing the value and collectibility of those few copies made. Kanzenban (完全版) is another term sometimes used to denote a special release that contains a complete collection from a series.

Bunkoban

A bunkoban (文庫版) edition is a typical Japanese novel-sized volume. These are generally A6 size (105 x 148 mm) and thicker than tankōbon, printed on thinner, much higher quality paper, and usually have a new cover designed specifically for the release. A bunko-ban contains more pages than a tankōbon, and the bunko edition of a given manga will consist of fewer volumes. If the original manga was a wide-ban release, the bunkoban release will generally have the same number of volumes. The term is commonly abbreviated to just bunko (without the -ban).

Wide-ban

A wide-ban (ワイド版 waidoban) edition is larger (A5 size) than a regular tankōbon. Many manga, particularly seinen manga and josei manga, are published in wide-ban editions after magazine serialization, and are never released in the tankōbon format that is common in shōnen manga and shōjo manga. When a series originally published in tankōbon format is re-released in wide-ban format, each volume will contain more pages than in the original edition, and the series will consist of fewer volumes.

Magazines

Books and magazines sold to boys (shōnen) and girls (shōjo) have distinctive cover art and are placed on different shelves in most bookstores. Manga magazines usually have many series running concurrently with approximately 20–40 pages allocated to each series per issue. Other magazines such as the anime fandom magazine Newtype feature single chapters within their monthly periodicals. These manga magazines, or "anthology magazines," as they are also known (colloquially "phone books"), are usually printed on low-quality newsprint and can be anywhere from 200 to more than 850 pages long. Manga magazines also contain one-shot comics and various four-panel yonkoma (equivalent to comic strips). Successful manga series can run for many years. Manga artists sometimes enter the field with a few "one-shot" manga projects; if these receive good reviews, they are continued.

Dōjinshi

Dōjinshi are produced by small amateur publishers outside of the mainstream commercial market in a similar fashion to small-press independently published comic books in the United States. Comiket, the largest comic book convention in the world, is devoted to dōjinshi. Held in Tokyo twice a year, it attracts over 510,000 visitors. Some dōjinshi are original stories, but many are parodies of popular manga and anime series or include fictional characters from them. Dōjinshi continue with a series' story or write an entirely new one using its characters, much like fan fiction. In 2007, sales of dōjinshi topped 27.73 billion yen (US$245 million).

Original webmanga, intended for online viewing, are drawn by enthusiasts of all levels of experience. If available in print, a webmanga can be ordered in graphic novel form.

Manga artists

As of 2006, about 3000 professional mangaka (漫画家, manga artists) were working in Japan.[27] Some artists may study for a few years at an art college or manga school, or take on an apprenticeship with another mangaka, before entering the world of manga as a professional artist. Some, like Naoko Takeuchi, creator of Sailor Moon, enter the field without being an assistant by applying to contests run by various magazines.

Many mangaka work in independent studios with a small staff of assistants The duties of assistants vary widely; some mangaka sketch out the basics of their manga and have assistants fill in all of the details, while others use assistants only for specific things Some mangaka have no assistants at all, and prefer to do everything themselves, though it is difficult to meet the tight publishing deadlines. Most often, assistants are responsible for the backgrounds and screentones in manga, while the mangaka draws and inks the main characters. Assistants rarely help the mangaka with the plot of a manga, beyond being a "sounding board" for ideas. The influence of the editor varies from manga to manga and company to company. Editors ensure that the manga is being produced at an even pace and that deadlines are met, and may comment on the layout of the manga panels and the art to keep the manga up to company standards. They may also make story suggestions.

International markets

In recent decades the manga industry has expanded worldwide through distribution companies that license and reprint manga in other languages. This has helped to compensate for the declining readership in domestic Japanese markets. The most receptive overseas markets for Japanese comic magazines have been in Asian countries such as Thailand, Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong, Indonesia, and mainland China. Some of these countries have original comic industries of their own, including Taiwan ("manhua") and South Korea ("manhwa").[28] Since the creation of original comics by local artists takes time, only a few are published every year and it is more profitable to translate the large volume of existing Japanese manga into local languages. Piracy is a problem in Asian countries, where local publishers produce unlicensed copies of Japanese manga, often on cheap-quality paper, that compete with legitimate magazines.

Since 1990 Japanese manga has had an increasing influence on both the styles and aesthetics of comics and on the marketing of comics internationally.[29] It has also played an important role in disseminating Japanese culture abroad, attracting young people from many countries to study Japanese and visit Japan as tourists.

Flipping and translation

Since Japanese is usually written from from top to bottom and right to left in works of fiction, manga is drawn and published this way in Japan. When various titles were first translated to other languages, the artwork and layouts were flipped and reversed in a process known as "flipping," so that the book could be read from left-to-right. Flipping may alter the original intentions of the creator (for example, if a character wears a shirt that reads "MAY," it reads "YAM" when flipped), and cause oddities with familiar asymmetrical objects or layouts, such as a car being depicted with gas pedal on the left and the brake on the right. Some creators (such as Akira Toriyama) did not approve of their work being modified this way, and requested that foreign versions retain the right-to-left format of the originals. Right-to-left formatting of manga has now become commonplace in North America.

Translated manga often includes cultural notes explaining details of Japanese culture that may not be familiar to foreign audiences.

Europe

The entrance of Japanese manga into Western markets was preceded by the release of anime movies and television series based on manga. During the 1970s, Italy and France began broadcasting Japanese anime cartoons as part of an effort to expand offerings on children’s television.[30] Children who watched these shows grew up preferring Japanese animated characters to European comic book heroes.

Since the mid-1990s, manga has found a wide readership in France, accounting for about one-third of comics sales there since 2004[31]

According to the Japan External Trade Organization, in 2006 sales of manga reached $212.6 million in France and Germany alone.[30] European publishers marketing manga translated into French include Glénat, Asuka, Casterman, Kana, and Pika. European publishers also translate manga into German, Italian, Spanish, Swedish, Danish and Dutch. Manga publishers based in the United Kingdom include Orionbooks/Gollancz and Titan Books. U.S. manga publishers such as Random House have a strong marketing presence in the U.K.

United States

Manga were introduced gradually into U.S. markets, first in association with anime and then independently[32] [33]Anime was more accessible to college-age young people who found it easier to obtain, subtitle and exhibit video tapes of anime than translate, reproduce, and distribute tankōbon-style manga books.[34] One of the first manga translated into English and marketed in the U.S. was Keiji Nakazawa's Barefoot Gen, an autobiographical story of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima issued by Leonard Rifas and Educomics (1980-1982).[5] More manga were translated between the mid-1980s and 1990s, including Golgo 13 in 1986, Lone Wolf and Cub from First Comics in 1987, and Kamui, Area 88, and Mai the Psychic Girl, also in 1987 and all from Viz Media-Eclipse Comics.[35][19] Others soon followed, including Akira from Marvel Comics-Epic Comics and Appleseed from Eclipse Comics in 1988, and later Iczer-1 (Antarctic Press, 1994) and Ippongi Bang's F-111 Bandit.

Japanese animation, like Akira, Dragon Ball, Neon Genesis Evangelion, and Pokémon, dominated the fan experience and the market until the mid-1990s.[34][35] In 1986 translator-entrepreneur Toren Smith founded Studio Proteus. Smith and Studio Proteus acted as agent and translator of many Japanese manga, including Masamune Shirow's Appleseed and Kōsuke Fujishima's Oh My Goddess!, for Dark Horse and Eros Comix, eliminating the need for American publishers to seek their own contacts in Japan.[5] Simultaneously, the Japanese publisher Shogakukan opened a U.S. market initiative with their U.S. subsidiary Viz, enabling Viz to draw directly on Shogakukan's catalogue and translation skills.

In the mid-1990s, anime and manga versions of Masamune Shirow's Ghost in the Shell, translated by Frederik L. Schodt and Toren Smith became popular in the United States. Another success of the mid-1990s was Sailor Moon.[35][36] By 1995–1998, the Sailor Moon manga had been exported to over 23 countries, including China, Brazil, Mexico, Australia, most of Europe and North America.[5] In 1998, Mixx Entertainment-TokyoPop issued U.S. manga book versions of Sailor Moon and CLAMP's Magic Knight Rayearth. In 1996, Mixx Entertainment founded TokyoPop in the United States to publish manga in trade paperbacks and, like Viz, began aggressive marketing of manga to both young male and young female demographics.

As manga became increasingly popular, new publishers entered the field and established publishers greatly expanded their catalogs.[5] By December 2007, at least 15 U.S. manga publishers had released 1,300 to 1,400 titles. Articles about manga were published in New York Times,[37] TIME magazine,[38] the Wall Street Journal,[39] and Wired magazine.[29]

Scanlation

Scanlation (also scanslation) is the unauthorized scanning, translation, editing and distribution of comics from a foreign language into the language of the distributors. The term is most often used for Japanese (manga), Korean (manhwa), and Chinese (manhua) comics. Scanlations are generally distributed for free via the Internet, either by direct download, BitTorrent or IRC. Scanlation is primarily a hobby which began as small individual efforts by manga fans and developed into a community-oriented practice.

Scanlation emerged in response to the unavailability of popular manga in many languages, and to the discrepancies between manga books published in Japan and books published in other countries. Often there is a long delay before new episodes are commercially published in other languages, and only a fraction of the episodes are made available. Some scanlations are produced because fans believe the original appeal of a manga has been compromised by commercial translators, who sometimes tone down the language, re-write jokes or make cultural changes. Scanlations are often viewed by fans as the only way to read comics that have not been licensed for release in their area. Historically, copyright holders have not requested scanlators to stop distribution before a work is licensed in the translated language, though it is technically illegal according to international copyright law. Some Japanese publishers have threatened scanlation groups with legal action. Licensing companies, such as Del Rey Manga, TOKYOPOP, and VIZ Media, have used the response to various scanlations as a factor in deciding which manga to license for translation and commercial release[40]

Non-Japanese manga

Manga enthusiasts continue to discuss whether the term “manga” can be legitimately applied to manga-style works created by non-Japanese artists. In the U.S., manga-like comics are called "Amerimanga," "world manga," or "original English-language manga" (OEL manga).[41]

A number of U.S. artists have drawn comics and cartoons influenced by manga. An early example was Vernon Grant, who drew manga-influenced comics while living in Japan in the late 1960s-early 1970s.[42] Others include Frank Miller's mid-1980s Ronin,[43] Adam Warren and Toren Smith's 1988 The Dirty Pair, Ben Dunn's 1993 Ninja High School, Stan Sakai's 1984 Usagi Yojimbo, and Manga Shi 2000 from Crusade Comics (1997).

In the early 2000s, several U.S. manga publishers began to market work by U.S. artists under the broad label of manga. In 2002, I.C. Entertainment, formerly Studio Ironcat and now out of business, launched a series of manga by U.S. artists called Amerimanga.[44] Seven Seas Entertainment followed suit with World Manga.[45] TokyoPop introduced original English-language manga (OEL manga) later renamed Global Manga.[46]

France has its own highly developed tradition of bande dessinée cartooning. Francophone artists have developed their own versions of manga, such as Frédéric Boilet's la nouvelle manga. Boilet has worked in France and in Japan, sometimes collaborating with Japanese artists.[47]

Awards

The Japanese manga industry has a large number of awards, most sponsored by publishers who include publication in one of their magazines as part of the prize. These awards include the Akatsuka Award for humorous manga, the Dengeki Comic Grand Prix for one-shot manga, the Kodansha Manga Award (multiple genre awards), the Seiun Award for best science fiction comic of the year, the Shogakukan Manga Award (multiple genres), the Tezuka Award for best new serial manga, and the Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize (multiple genres). In May 2007, the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs began awarding an annual International Manga Award. [48]

Notes

- ↑ Jocelyn Bouquillard and Christophe Marquet, Hokusai: First Manga Master (New York: Abrams, 2007, ISBN 0810993414).

- ↑ Isao Shimizu, 日本漫画の事典 : 全国のマンガファンに贈る (Nihon Manga no Jiten) (Sun lexica, 1985, ISBN 4385155860), 53-54, 102-103 (Japanese)

- ↑ Sharon Kinsella, Adult Manga: Culture and Power in Contemporary Japanese Society. (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0824823184).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Frederik L. Schodt, Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics (Tokyo: Kodansha, 1986, ISBN 978-0870117527).

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 Frederik L. Schodt, Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga. (Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge Press, 1996, ISBN 978-1880656235).

- ↑ Kinko Ito, "Growing up Japanese reading manga." International Journal of Comic Art 6 (2004):392-401.

- ↑ Adam Kern, Manga from the Floating World: Comicbook Culture and the Kibyōshi of Edo Japan (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0674022669).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Matt Thorn, Shôjo Manga—Something for the Girls The Japan Quarterly 48(3) (July-September 2001).

- ↑ The Japanese constitution is in the Kodansha encyclopedia Japan: Profile of a Nation, Revised Ed. (Tokyo: Kodansha, 1999, ISBN 4770023847), 692-715. Article 9: page 695; article 21: page 697.

- ↑ Frederik L. Schodt, The Astro Boy Essays: Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, and the Manga/Anime Revolution (Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge Press, 2007, ISBN 978-1933330549).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Paul Gravett, Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics. (NY: Harper Design, 2004, ISBN 1856693910).

- ↑ William Lee, "From Sazae-san to Crayon Shin-Chan" In: Timothy J. Craig, (ed.) Japan Pop!: Inside the World of Japanese Popular Culture (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2000, ISBN 978-0765605610).

- ↑ Masami Toku, Shojo Manga: Girl Power! (Chico, CA: Flume Press/California State University Press, 2005, ISBN 1886226105).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 John A. Lent, (ed.), Illustrating Asia: Comics, Humor Magazines, and Picture Books (Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai'i Press, 2001, ISBN 0824824717).

- ↑ Fusami Ōgi, "Female subjectivity and shōjo (girls) manga (Japanese comics): shōjo in "Ladies' Comics and Young Ladies' Comics." Journal of Popular Culture 36(4) (2004):780-803.

- ↑ Patrick Drazen, Anime Explosion!: the What? Why? & Wow! of Japanese Animation (Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge,2003, ISBN 9781880656723).

- ↑ Anne Allison, "Sailor Moon: Japanese superheroes for global girls." In: Timothy J. Craig, (ed.), Japan Pop! Inside the World of Japanese Popular Culture (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 978-0765605610), 259-278.

- ↑ Gilles Poitras, Anime Essentials: Everything a Fan Needs to Know (Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge, 2001, ISBN 1880656531).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Jason Thompson, Manga: The Complete Guide (New York: Ballantine Books, 2007, ISBN 978-0345485908).

- ↑ Robin E. Brenner, Understanding Manga and Anime (Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited, 2007, ISBN 978-1591583325).

- ↑ Timothy Perper and Martha Cornog, "Eroticism for the masses: Japanese manga comics and their assimilation into the U.S." Sexuality & Culture 6(1) (2002): 3-126.

- ↑ Oh My Goddess! Anime News Network. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ↑ Ken Akamatsu, Negima Anime News Network. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ↑ Hanaukyo Maid Team Anime News Network. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ↑ Mari Kotani, "Metamorphosis of the Japanese girl: The girl, the hyper-girl, and the battling beauty" Mechademia: An Academic Forum for Anime, Manga and the Fan Arts 1 (2006): 162-170.

- ↑ Japanese Manga Market Drops Below 500 Billion ComiPress (March 10, 2007). Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ↑ Helen McCarthy, 500 Manga Heroes & Villains (Hauppauge, NY: Chrysalis Book Group, 2006, ISBN 978-0764132018).

- ↑ Lexicon: Manhwa: 만화 Anime News Network. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Daniel H. Pink, "Japan, Ink: Inside the Manga Industrial Complex" Wired Magazine 15 (11) (October 22, 2007). Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Jennifer Fishbein, "Europe's Manga Mania" BusinessWeek (December 26, 2007).

- ↑ "Manga-mania-in-france" Anime News Network. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ↑ Susan J. Napier, Anime: From Akira to "Princess Mononoke" (NY: Palgrave, 2000, ISBN 0312238630).

- ↑ Jonathan Clements and Helen McCarthy, The Anime Encyclopedia: A Guide to Japanese Animation Since 1917 (Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge Press, 2006, ISBN 1933330104).

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Sean Leonard, "Progress Against the Law: Fan Distribution, Copyright, and the Explosive Growth of Japanese Animation" Massachusetts Institute of Technology, September 12, 2004. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Fred Patten, Watching Anime, Reading Manga: 25 Years of Essays and Reviews (Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge Press, 2004, ISBN 978-1880656921).

- ↑ Adam Arnold, "Full Circle: The Unofficial History of MixxZine" ANIMEfringe (June 2000). Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ↑ Sarah Glazer, "Manga for Girls" The New York Times (September 18, 2005), Retrieved jUNE 8, 2023.

- ↑ Coco Masters, "America is Drawn to Manga" TIME Magazine (August 10, 2006),

- ↑ Bianca Bosker, "Manga Mania" The Wall Street Journal (August 31, 2007). Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ↑ Jeff Yang, "No longer an obscure cult art form, Japanese comics are becoming as American as apuru pai" SFGate (June 14, 2006). Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ↑ World Manga Anime News Network. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ↑ Bhob Stewart, "Screaming Metal," The Comics Journal 94 (October 1984).

- ↑ Andy Shaw, "Ronin" Grovel (July 1, 2006). Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ↑ I.C. promotes AmeriManga Anime News Network (November 27, 2002). Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ↑ "Correction: World Manga" Anime News Network (May 10, 2006). Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ↑ "Tokyopop To Move Away from OEL and World Manga Labels" Anime News Network (May 5, 2006). Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ↑ Frédéric Boilet and Kan Takahama, Mariko Parade (Castalla-Alicante, Spain: Ponent Mon, 2004, ISBN 849334091X).

- ↑ Japan's Foreign Minister Creates Foreign Manga Award Anime News Network (May 22, 2007). Retrieved June 8, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boilet, Frédéric, and Kan Takahama. Mariko Parade. Castalla-Alicante, Spain: Ponent Mon, 2004. ISBN 849334091X

- Bouquillard, Jocelyn, and Christophe Marquet. Hokusai: First Manga Master. New York: Abrams, 2007. ISBN 0810993414

- Brenner, Robin E. Understanding Manga and Anime. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited, 2007. ISBN 978-1591583325

- Clements, Jonathan, and Helen McCarthy. The Anime Encyclopedia: A Guide to Japanese Animation Since 1917. Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge Press, 2006. ISBN 1933330104

- Craig, Timothy J. (ed.). Japan Pop!: Inside the World of Japanese Popular Culture. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2000. ISBN 978-0765605610

- Drazen, Patrick. Anime Explosion!: the What? Why? & Wow! of Japanese Animation. Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge, 2003. ISBN 9781880656723

- Gravett, Paul. Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics. NY: Harper Design. 2004. ISBN 1856693910

- Katzenstein, Peter J., and Takashi Shiraishi. Network Power: Japan in Asia. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0801483738

- Kern, Adam. Manga from the Floating World: Comicbook Culture and the Kibyōshi of Edo Japan. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0674022669

- Kinsella, Sharon. Adult Manga: Culture and Power in Contemporary Japanese Society. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0824823184

- Kittelson, Mary Lynn. The Soul of Popular Culture: Looking at Contemporary Heroes, Myths, and Monsters. Chicago: Open Court. 1998. ISBN 978-0812693638

- Kodansha. Japan: Profile of a Nation, Revised Ed. Tokyo: Kodansha, 1999. ISBN 4770023847

- Lent, John A. (ed.). Illustrating Asia: Comics, Humor Magazines, and Picture Books. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai'i Press, 2001. ISBN 0824824717

- McCarthy, Helen. 500 Manga Heroes & Villains. Hauppauge, NY: Chrysalis Book Group, 2006. ISBN 978-0764132018

- Napier, Susan J. Anime: From Akira to "Princess Mononoke." NY: Palgrave, 2000. ISBN 0312238630

- Patten, Fred. Watching Anime, Reading Manga: 25 Years of Essays and Reviews. Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge Press, 2004. ISBN 978-1880656921

- Poitras, Jilles. 2001. Anime Essentials: Everything a Fan Needs to Know. Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge. ISBN 1880656531

- Schodt, Frederik L. Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics. Tokyo: Kodansha. 1986. ISBN 978-0870117527

- Schodt, Frederik L. Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga. Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge Press, 1996. ISBN 978-1880656235

- Schodt, Frederik L. The Astro Boy Essays: Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, and the Manga/Anime Revolution. Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge Press, 2007. ISBN 978-1933330549

- Shimizu, Isao. 日本漫画の事典 : 全国のマンガファンに贈る (Nihon Manga no Jiten). Sun lexica, 1985. ISBN 4385155860. (Japanese)

- Thompson, Jason. Manga: The Complete Guide. New York: Ballantine Books, 2007. ISBN 978-0345485908

- Toku, Masami. Shojo Manga: Girl Power! Chico, CA: Flume Press/California State University Press, 2005, ISBN 1886226105

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Manga history

- Tankōbon history

- Hokusai history

- Santō_Kyōden history

- Rakuten_Kitazawa history

- Osamu_Tezuka history

- Machiko_Hasegawa history

- Astro_Boy history

- Gekiga history

- Manga_outside_Japan history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.