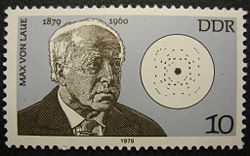

Max von Laue

|

Max von Laue | |

|---|---|

Max von Laue | |

| Born |

October 9 1879 |

| Died | April 24 1960 (aged 80) |

| Nationality | |

| Field | Physicist |

| Institutions | University of Zürich University of Frankfurt University of Berlin Max Planck Institute |

| Alma mater | University of Strassburg University of Göttingen University of Munich University of Berlin University of Göttingen |

| Academic advisor | Max Planck |

| Notable students | Fritz London Leó Szilárd Max Kohler Erna Weber |

| Known for | Diffraction of X-rays |

| Notable prizes | |

Max Theodore Felix von Laue (Pfaffendorf, near Koblenz, October 9, 1879 – April 24, 1960 in Berlin) was a German physicist. He demonstrated that X-rays were electromagnetic waves by showing that they produce a diffraction pattern when they pass through a crystal, similar to the pattern light exhibits when it passes through a diffraction grating. For this discovery, he was awarded the Nobel prize in 1914. He resisted the policies of Nazi Germany during World War II, although he worked under the regime throughout the course of the war.

Life

Max von Laue was born in Pfaffendorf, near Koblenz, in what was then Prussia, the son of Julius von Laue, a military official who was raised to the rank of baron. Von Laue's father traveled quite a bit, the result being that he had a somewhat nomadic childhood. It was while he attended a protestant school in Strassburg that his interest in science began to blossom. He was particularly drawn to study of optics, and more particularly, to the wave theory of light.

In 1898, after passing his Abitur in Strassburg, Laue entered his compulsory year of military service, after which he began his studies in mathematics, physics, and chemistry, in 1899, at the University of Strasbourg, the Georg-August University of Göttingen, and the Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich (LMU). At Göttingen, he was greatly influenced by the physicists Woldemar Voigt and Max Abraham and the mathematician David Hilbert. After only one semester at Munich, he went to the Friedrich-Wilhelms-University of Berlin (Today: Humboldt University of Berlin), in 1902. There, he studied under Max Planck, who gave birth to the quantum theory revolution on 14 December 1900, when he delivered his famous paper before the Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft.[1] [2] At Berlin, Laue attended lectures by Otto Lummer on heat radiation and interference spectroscopy, the influence of which can be seen in Laue’s dissertation on interference phenomena in plane-parallel plates, for which he received his doctorate in 1903.[3] Thereafter, Laue spent 1903 to 1905 at Göttingen. Laue completed his Habilitation [4] in 1906 under Arnold Sommerfeld at LMU.[5][6][7][8]

Career

In 1906, Laue became a Privatdozent in Berlin and an assistant to Planck. He also met Albert Einstein for the first time; they became friends and von Laue went on to contribute to the acceptance and development of Einstein’s theory of relativity. Laue continued as assistant to Planck until 1909. In Berlin, he worked on the application of entropy to radiation fields and on the thermodynamic significance of the coherence of light waves.[6] [8] While he was still a Privatdozent at LMU, von Laue married Magdalene Degen. The couple had two children.[8]

Discovery of X-ray diffraction by crystals

From 1909 to 1912, he was a Privatdozent at the Institute for Theoretical Physics, under Arnold Sommerfeld, at LMU. During the 1911 Christmas recess and in January 1912, Paul Peter Ewald was finishing the writing of his doctoral thesis under Sommerfeld. It was on a walk through English Garden in Munich in January, that Ewald told von Laue about his thesis topic. The wavelengths of concern to Ewald were in the visible region of the spectrum and hence much larger than the spacing between the resonators in Ewald’s crystal model. Von Laue seemed distracted and wanted to know what would be the effect if much smaller wavelengths were considered. He already knew that the wavelength of x-rays had been estimated, and that it was less than the estimated spacing of the atom lattices in crystals. This would make crystals a perfect tool to study the diffraction of x-rays. He arranged, with some resistance, to have the experiment performed by Paul Knipping and Walter Friedrich in which a beam of x-rays was directed toward a crystal of copper sulfate. The pattern that this made on photographic film was consistent with diffraction patterns when visible light is passed through much wider gratings. In June, Sommerfeld reported to the Physikalische Gesellschaft of Göttingen on the successful diffraction of x-rays by von Laue, Knipping and Friedrich at LMU, for which von Laue would be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1914. The exact arrangement of atoms in a variety of crystals, a question that Laue had not been able to completely solve, was soon thereafter elucidated by William and Lawrence Bragg with the help of X-ray diffraction. This father-and-son team received the Nobel prize for their efforts in 1915.

While at Munich, he wrote the first volume of his book on relativity during the period 1910 to 1911.[9] [10][7][8]

In 1912, Laue was called to the University of Zurich as an extraordinarius professor of physics. In 1913, his father was raised to the ranks of hereditary nobility; Laue then became von Laue.[8]

Wold War I

From 1914 to 1919, von Laue was at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University of Frankfurt am Main as ordinarius professor of theoretical physics. From 1916, he was engaged in vacuum tube development, at the Bayerische Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg, for use in military telephony and wireless communications.[7][6] [8]

Superconductivity

In 1919, von Laue was called to the Humboldt University of Berlin as ordinarius professor of theoretical physics, a position he held until 1943, when von Laue was declared emeritus, with his consent and one year before the mandatory retirement age. At the University in 1919, other notables were Walther Nernst, Fritz Haber, and James Franck. Von Laue, as one of the organizers of the weekly Berlin Physics Colloquium, typically sat in the front row with Nernst and Albert Einstein, who would come over from the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für Physik (Today: Max-Planck-Institut für Physik) in Dahlem-Berlin, where he was the Director. Among von Laue’s notable students at the University were Leó Szilárd, Fritz London, Max Kohler, and Erna Weber. In 1921, he published the second volume of his book on relativity. [7] [3] [11]

As a consultant to the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt (Today: Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt), von Laue met Walther Meissner who was working there on superconductivity, the tendancy of materials to conduct electricity with little resistance at very low temperatures. Von Laue showed in 1932 that the threshold of the applied magnetic field which destroys superconductivity varies with the shape of the body. Von Laue published a total of 12 papers and a book on superconductivity. One of the papers was co-authored with Fritz London and his brother Heinz.[12] [6] Meissner published a biography on von Laue in 1960.[13]

Kaiser Wilhelm Institute

The Kaiser-Wilhelm Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften (Today: Max-Planck Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften) was founded in 1911. Its purpose was to promote the sciences by founding and maintaining research institutes. One such institute was the Kaiser-Wilhelm Institut für Physik (KWIP) founded in Dahlem-Berlin in 1914, with Albert Einstein as director. Von Laue was a trustee of the institute from 1917, and in 1922 he was appointed deputy director, whereupon von Laue took over the administrative duties from Einstein. Einstein was traveling abroad when Adolf Hitler became Chancellor in January 1933, and Einstein did not return to Germany. Von Laue then became acting director of the KWIP, a position he held until 1946 or 1948, except for the period 1935 to 1939, when Peter Debye was director. In 1943, to avoid casualties to the personnel, the KWIP moved to Hechingen. It was at Hechingen that von Laue wrote his book on the history of physics Geschichte der Physik, which was eventually translated into seven other languages.[14] [15] [6]

Von Laue's resistance to the Third Reich

Von Laue was in opposition to National Socialism in general and their Deutsche Physik in particular – the former persecuted the Jews, in general, and the latter, among other things, put down Einstein’s theory of relativity as Jewish physics. Von Laue secretly helped scientific colleagues persecuted by National Socialist policies to emigrate from Germany, but he also openly opposed them. An address on September 18, 1933 at the opening of the physics convention in Würzburg, opposition to Johannes Stark, an obituary note on Fritz Haber in 1934, and attendance at a commemoration for Haber are examples which clearly illustrate von Laue’s courageous, open opposition:

- Von Laue, as chairman of the Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft, gave the opening address at the 1933 physics convention. In it, he compared the persecution of Galileo and the oppression of his scientific views on the Solar theory of Copernicus to the then conflict and persecution over the theory of relativity by the proponents of Deutsche Physik, against the work of Einstein, labeled “Jewish physics.”

- Johannes Stark, who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1919 and who had attempted to become the Führer of German physics, was a proponent of Deutsche Physik. Against the unanimous advice of those consulted, Stark was appointed President of the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt in May 1933. However, von Laue successfully blocked Stark’s regular membership in the Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- Haber received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918. In spite of this and his many other contributions to Germany, he was compelled to emigrate from Germany as a result of the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, which removed Jews from their jobs. Von Laue’s obituary note[16] praising Haber and comparing his forced emigration to the expulsion of Themistocles from Athens was a direct affront to the policies of National Socialism.

- In connection with Haber, Planck and von Laue organized a commemoration event held in Dahlem-Berlin on 29 January 1935, the first anniversary of Haber’s death – attendance at the event by professors in the civil service had been expressly forbidden by the government. While many scientific and technical personnel were represented at the memorial by their wives, von Laue and Wolfgang Heubner were the only two professors to attend.[17] [18] This was yet another blatant demonstration of von Laue’s opposition to National Socialism. The date of the first anniversary of Haber’s death was also one day before the second anniversary of National Socialism seizing power in Germany, thus further increasing the affront given by holding the event.

The speech and the obituary note earned von Laue government reprimands. Furthermore, in response to von Laue blocking Stark’s regular membership in the Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Stark, in December 1933, Stark had von Laue sacked from his position as advisor to the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt (PTR), which von Laue had held since 1925. (Chapters 4 and 5, in Walker’s Nazi Science: Myth, Truth, and the Atomic Bomb, present a more detailed account of the struggle by von Laue and Plank against the Nazi takeover of the Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.[19]) [12] [20] [21] [22] [23]

Post-war years

On April 23, 1945, French troops entered Hechingen, followed the next day by a contingent of Operation Alsos – an operation to investigate the German nuclear energy effort, seize equipment, and prevent German scientists from being captured by the Russians. The scientific advisor to the Operation was the Dutch-American physicist Samuel Goudsmit, who, adorned with a steel helmet, appeared at von Laue’s home. Von Laue was taken into custody and taken to Huntington, England and interned at Farm Hall, with other scientists thought to be involved in nuclear research and development.[12]

While incarcerated, von Laue was a reminder to the other detainees that one could survive the Nazi reign without having “compromised”; this alienated him from others being detained.[24] During his incarceration, von Laue wrote a paper on the absorption of X-rays under the interference conditions, and it was later published in Acta Crystallographica.[12] On 2 October 1945, von Laue, Otto Hahn, and Werner Heisenberg, were taken to meet with Henry Hallett Dale, president of the Royal Society, and other members of the Society. There, von Laue was invited to attend the 9 November 1945 Royal Society meeting in memory of the German physicist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, who discovered X-rays; permission was, however, not forthcoming from the military authorities detaining von Laue.[12]

Max Plank Institute

Von Laue was returned to Germany early in 1946. He went back to being acting director of the KWIP, which had been moved to Göttingen. It was also in 1946 that the Kaiser-Wilhelm Gesellschaft was renamed the Max-Planck Gesellschaft, and, likewise, the Kaiser-Wilhelm Institut für Physik became the Max-Planck Institut für Physik. Von Laue also became an adjunct professor at the Georg-August University of Göttingen. In addition to his administrative and teaching responsibilities, von Laue wrote his book on superconductivity, Theorie der Supraleitung, and revised his books on electron diffraction, Materiewellen und ihre Interferenzen, and the first volume of his two-volume book on relativity.[12] [25][7]

In July 1946, von Laue went back to England, only four months after having been interned there, to attend an international conference on crystallography. This was a distinct honor, as he was the only German invited to attend. He was extended many courtesies by the British officer who escorted him there and back, and a well-known English crystallographer as his host; von Laue was even allowed to wander around London on his own free will.[12]

Reorganization of German science

After the War, there was much to be done in re-establishing and organizing German scientific endeavors. Von Laue participated in some key roles. In 1946, von Laue initiated the founding of the Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft in only the British Zone, as the Allied Control Council would not initially allow organizations across occupation zone boundaries. During the war, the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt had been dispersed; von Laue, from 1946 to 1948, worked on its re-unification across three zones and its location at new facilities in Braunschweig. Additionally, it took on a new name as the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt, but administration was not taken over by Germany until after the formation of the Deutsche Bundesrepublik on 23 May 1949. Circa 1948, the President of the American Physical Society asked von Laue to report on the status of physics in Germany; von Laue’s report was published in 1949 in the American Journal of Physics.[26] In 1950, von Laue participated in the creation of the Verband Deutsches Physikalischer Gesellschaften, formerly affiliated under the Nordwestdeutsch Physikalische Gesellschaft.[12] [27][7]

Last years

In April 1951, von Laue became director of the Max-Planck Institut für physikalische Chemie und Elektrochemie, a position he held until 1959. In 1953, at the request of von Laue, the Institute was renamed the Fritz Haber Institut für physikalische Chemi und Elektrochemie der Max-Planck Gesellschaft.[12] [28]

On April 8, 1960, while driving to his laboratory, von Laue’s car was struck by a motor cyclist, who had received his license only two days earlier. The cyclist was killed and von Laue’s car was overturned. Von Laue died from his injuries sixteen days later on April 24.[6]

Legacy

Von Laue was prescient enough to realize that crystals could be used to diffract X-rays in much the same way that light waves are diffracted by optical gratings. This simple observation, when properly investigated, led to the opening of the new field of X-ray crystallography. The techniques pioneered by von Laue and perfected by the Braggs led to important discoveries, such as the unraveling of the helical structure of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) in the 1950s.

Von Laue helped to show by example that one can be a positive influence in a political regime that is bent on destructive policies, such as was Hitler's Germany in the 1930s and 1940s. Von Laue's role in opposing Nazi plans to dominate German science allowed him greater freedom than other German scientists to pursue his work after World War II.

Organizations

- 1919 – Corresponding member of the Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften [8]

- 1921 – Regular member of the Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften [7]

- From 1921 – Chairman of the physics commission of the Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft (Renamed in 1937: Deutsche Gemeinschaft zur Erhaltung und Förderun der Forschung. No longer active by 1945.) [29]

- From 1922 – Member of the Board of Trustees of the Potsdam Astrophysics Observatory[7]

- 1925 - 1933 – Advisor to the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt (Today: Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt).[7] Von Laue had been sacked in 1933 from his advisory position by Johannes Stark, Nobel Prize recipient and President of the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt, in retribution for von Laue’s open opposition to the Nazis by blocking Stark’s regular membership in the Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- 1931 - 1933 – Chairman of the Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft[7]

- Memberships in the Russian Academy of Sciences, the Kant Society, the Academy of Sciences of Vienna, the American Physical Society, the American Physical Society, the Société Française de Physique and the Société Française de Mineralogie et Crystallographie.[6]

- Corresponding Member of the Academies of Sciences of Göttingen, Munich, Turin, Stockholm, Rome (Papal), Madrid, the Academia dei Lincei of Rome, and the Royal Society of London.[6]

Honors

- 1932 – Max-Planck Medal of the Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft [6]

- 1952 – Knight of the Order Pour le Mérite[6]

- 1953 – Grand Cross with Star for Federal Services[6]

- 1957 – Officer of the Legion of Honour of France[6]

- 1959 – Helmholtz Medal of the East-Berlin Academy of Sciences[8]

- Landenburg Medal[6]

- Bimala-Churn-Law Gold Medal of the Indian Association at Calcutta[6]

Notes

- ↑ B. L. van der Waerden (ed.), Sources of Quantum Mechanics (Dover, 1968), 1.

- ↑ Max Planck, Zur Theorie des Gesetzes der Energieverteilung im Normalspektrum, Verhandlungen der Deutschen Physikalische Gesellschaft 2 237-245 (1900) as cited in Hans Kango (ed.) and translated by D. ter Haar and Stephen G. Bush Planck’s Original Papers in Quantum Physics: German and English Edition (Taylor and Francis, 1972), 60.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Max von Laue – Mathematics Genealogy Project. Max von Laue, Ph.D., Universität Berlin, 1903, Dissertation title: Über die Interferenzerscheinungen an planparallelen Platten. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ↑ Habilitation title: "Über die Entropie von interferierenden Strahlenbündeln"

- ↑ Walker, 1995, 73.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 Max von Laue – Nobel Prize Biography. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 Hentschel, 1996, Appendix F, see entry for Max von Laue.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 Max von Laue Biography – Deutsches Historisches Museum Berlin. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ↑ Ewald 50 Years of X-Ray Diffraction Chapter 4, 37-42.

- ↑ Jungnickel, Volume 2, 1990, 284-285.

- ↑ Lanouette, 1992, 56-58.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 Max von Laue, My Development as a Physicist Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ↑ Walther Meißner, Max von Laue als Wissenschaftler und Mensch (Verl. d. Bayer. Akademie d. Wissenschaften, 1960) and (C. H. Beck Verlag, 1986).

- ↑ Hentschel, 1966, Appendix F, see entries for von Laue and Debye.

- ↑ Hentschel, 1966, Appendix A, see entries for KWG and KWIP.

- ↑ Max von Laue Naturwissenschaften 22 97 (1934).

- ↑ Hentschel, 1996, Document #29, 76-78: See Footnote #3.

- ↑ Hentsche, 1996, Document #120, 400-402: A letter from Lise Meitner to Otto Hahn.

- ↑ Walker, 1995, 65 – 122.

- ↑ Hentschel, 1966, Appendix F, see entries for Max von Laue, Johannes Stark, and Fritz Haber.

- ↑ Hentschel, 1966, Appendix A, see entry for the DFG.

- ↑ Heilbron, 1996, 159-162 and 167-168.

- ↑ Beyerchen, 1977, 64-69 and 208-209.

- ↑ Bernstein, 2001, pp. 333-334.

- ↑ Hentschel, 1996, Appendix A, see entries on KWG and KWIP.

- ↑ Max von Laue A Report on the State of Physics in Germany, American Journal of Physics 17 (3) 137-141 (1949)

- ↑ Hentschel, 1996, Appendix A, see entries on KWG and KWIP.

- ↑ Hentschel, 1996, Appendix A, see entry on KWIPC.

- ↑ Hentschel, 1966, Appendix A, see entry for NG.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beyerchen, Alan D. Scientists under Hitler: politics and the physics community in the Third Reich. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1977. ISBN 0300018304

- Bernstein, Jeremy. Hitler's uranium club: the secret recordings at Farm Hall. New York: Copernicus, 2001. ISBN 0387950893

- Ewald, Paul Peter. Fifty years of X-ray diffraction dedicated to the International Union of Crystallography on the occasion of the commemoration meeting in Munich, July 1962. Utrecht: Published for the International Union of Crystallography by A. Oosthoek's Uitgeversmij, 1962. ISBN 0738206938

- Heilbron, J. L. The dilemmas of an upright man: Max Planck and the Fortunes of German Science. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000. ISBN 0674004396

- Hentschel, Klaus, editor and and Ann M. Hentschel, editorial assistant and Translator. Physics and National Socialism: An Anthology of Primary Sources. Basel: Birkhäuser, 1996. ISBN 0817653120

- Herneck, Friedrich. Max von Laue. Leipzig: Teubner, 1979.

- Jammer, Max. The Conceptual Development of Quantum Mechanics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1966.

- Jungnickel, Christa and and Russell McCormmach. Intellectual Mastery of Nature. Theoretical Physics from Ohm to Einstein, Volume 2: The Now Mighty Theoretical Physics, 1870 to 1925. University of Chicago Press, 1990. ISBN 0226415856

- Lanouette, William and with Bela Silard. Genius in the Shadows: A Biography of Leó Szilárd the Man Behind the Bomb. New York: Scribners, 1992. ISBN 0684190117

- Mehra, Jagdish and and Helmut Rechenberg. The Historical Development of Quantum Theory. Volume 1 Part 1 The Quantum Theory of Planck, Einstein, Bohr and Sommerfeld 1900 – 1925: Its Foundation and the Rise of Its Difficulties. New York: Springer, 2001. ISBN 0387951741

- Mehra, Jagdish and and Helmut Rechenberg. The Historical Development of Quantum Theory. Volume 1 Part 2 The Quantum Theory of Planck, Einstein, Bohr and Sommerfeld 1900 – 1925: Its Foundation and the Rise of Its Difficulties. New York: Springer, 2001. ISBN 038795175X

- Rosenthal-Schneider, Ilse. Begegnungen mit Einstein, von Laue und Planck. Realität und wissenschaftliche Wahrheit. Braunschweig: Vieweg, 1988. ISBN 3528089709

- Rosenthal-Schneider, Ilse. Reality and Scientific Truth: Discussions with Einstein, von Laue, and Planck. Wayne State University, 1980. ISBN 0814316506

- van der Waerden, B. L. (ed.). Sources of Quantum Mechanics. Dover, 1968.

- Walker, Mark H. German National Socialism and the Quest for Nuclear Power, 1939-1949. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 0521438047

- Walker, Mark H. Nazi science: myth, truth, and the German atomic bomb. New York: Plenum Press, 1995. ISBN 0306449412

External links

All links retrieved November 8, 2022.

- Max von Laue - Nobel Prize Biography.

- Nobel Lecture Address - Max von Laue Concerning the Detection of X-ray Interferences, November 12, 1915.

- Nobel Presentation Address - An account of von Laue's work is by Professor G. Granqvist, Chairman of the Nobel Committee for Physics.

| ||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.