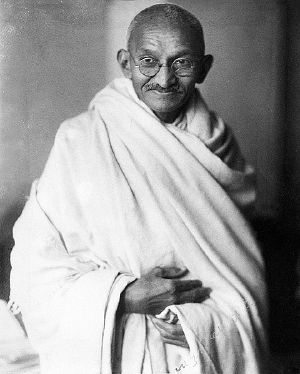

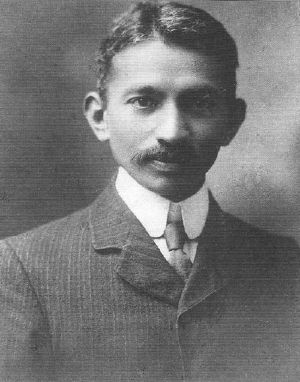

Mohandas K. Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (Devanagari: मोहनदास करमचन्द गांधी; Gujarati: મોહનદાસ કરમચંદ ગાંધી; October 2, 1869 – January 30, 1948) was one of the most important leaders in the fight for freedom in India and its struggle for independence from the British Empire. It was his philosophy of Satyagraha or nonviolent non-compliance (being willing to suffer so that the opponent can realize the error of their ways)—which led India to independence, and has influenced social reformers around the world, including Martin Luther King, Jr. and the American civil rights movement, Steve Biko and the freedom struggles in South Africa, and Aung San Suu Kyi in Myanmar.

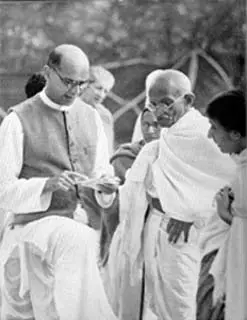

As a member of a privileged and wealthy family, he studied law in England at the turn of the twentieth century, and practiced law in South Africa for 20 years. But it was his role as a social reformer than came to dominate his thinking and actions. In South Africa he successfully led the Indian community to protest discriminatory laws and situations. In India, he campaigned to eliminate outdated Hindu customs, such as satee, dowry, and the condition of the untouchables. He led poor farmers in a reform movement in Bihar and Gujarat. On a national level, he led thousands of Indians on the well-known Dandi Salt March, a nonviolent resistance to a British tax. As a member and leader of the Indian National Congress, he led a nationwide, nonviolent campaign calling on the British to “Quit India.” In each case, the British government found itself face to face with a formidable opponent, one to whom, in most cases, they ceded.

The strength of his convictions came from his own moral purity: he made his own clothes—the traditional Indian dhoti and shawl, and lived on a simple vegetarian diet. He took a vow of sexual abstinence at a relatively early age and used rigorous fasts—abstaining from food and water for long periods—for self-purification as well as a means for protest. Born a Hindu of the vaishya (or “business”) caste, he came to value all religion, stating that he found all religions to be true; all religions to have some error; and all religions to be “almost as dear to me as my own.”[1] He believed in an unseen power and moral order that transcends and harmonizes all people.

Gandhi was equally devoted to people, rejecting all caste, class and race distinctions. In truth, it was probably the power of his conscience and his compassion for others that moved him to greatness. He is commonly known both in India and elsewhere as “Mahatma Gandhi,” a Sanskrit title meaning “Great Soul” given to him in recognition of his sincere efforts to better the lives of others, and his own humble lifestyle. In India he is also fondly called Bapu, which in many Indian languages means “father.” In India, his birthday, October 2, is commemorated each year as Gandhi Jayanti, and is a national holiday.

Early Life

Gandhi was born into a Hindu Modh family of the vaishya, or business, caste in Porbandar, Gujarat, India in 1869. His father, Karamchand Gandhi, was the diwan or chief minister of Porbandar under the British—a position earlier held by his grandfather and great-grandfather before him. His mother, Putlibai, was a devout Hindu of the Pranami Vaishnava order, and Karamchand's fourth wife. His father’s first two wives each died (presumably in childbirth) after bearing him a daughter, and the third was incapacitated and gave his father permission to marry again.

Gandhi grew up surrounded by the Jain influences common to Gujarat, so learned from an early age the meaning of ahimsa (non-injury to living thing), vegetarianism, fasting for self-purification, and a tolerance for members of other creeds and sects. At the age of 13 (May 1883), by his parents’ arrangement, Gandhi married Kasturba Makhanji (also spelled "Kasturbai" or known as "Ba"), who was the same age as he. They had four sons: Harilal Gandhi, born in 1888; Manilal Gandhi, born in 1892; Ramdas Gandhi, born in 1897; and Devdas Gandhi, born in 1900. Gandhi continued his studies after marriage, but was a mediocre student at Porbandar and later Rajkot. He barely passed the matriculation exam for Samaldas College at Bhavnagar, Gujarat in 1887. He was unhappy at college, because his family wanted him to become a barrister. He leapt at the opportunity to study in England, which he viewed as "a land of philosophers and poets, the very centre of civilization."

At the age of 18 on September 4, 1888, Gandhi set sail for London to train as a barrister at the University College, London. Prior to leaving India, he made a vow to his mother, in the presence of a Jain monk Becharji, the he would observe the Hindu abstinence of meat, alcohol, and promiscuity. He kept his vow on all accounts. English boiled vegetables were distasteful to Gandhi, so he often went without eating, as he was too polite to ask for other food. When his friends complained he was too clumsy for decent society because of his refusal to eat meat, he determined to compensate by becoming an English gentleman in other ways. This determination led to a brief experiment with dancing. By chance he found one of London's few vegetarian restaurants and a book on vegetarianism which increased his devotion to the Hindu diet. He joined the Vegetarian Society, was elected to its executive committee, and founded a local chapter. He later credited this with giving him valuable experience in organizing institutions.

While in London, Gandhi rediscovered other aspects of the Hindu religion as well. Two members of the Theosophical Society (a group founded in 1875 to further universal brotherhood through the study of Buddhist and Hindu Brahmanistic literature) encouraged him to read the classic writings of Hinduism. This whetted his appetite for learning about religion, and he studied other religions as well—Christianity, Buddhism and Islam. It was in England that he first read the Bhagavad Gita, from which he drew a great deal of inspiration, as he also did from Jesus' Sermon on the Mount. He later wrote a commentary on the Gita. He interpreted the battle scene, during which the dialogue between Krishna and Arjuna takes place, as an allegory of the eternal struggle between good and evil.

He returned to India after being admitted to the bar of England and Wales. His readjustment to Indian life was difficult due to the fact that his mother had died while he was away (his father died shortly before he left for England), and because some of his extended family shunned him—believing that a foreign voyage had made him unclean and was sufficient cause to excommunicate him from their caste.

After six months of limited success in Bombay (Mumbai) establishing a law practice, Gandhi returned to Rajkot to earn a modest living drafting petitions for litigants. After an incident with a British officer, he was forced to close down that business as well. In his autobiography, he describes this incident as a kind of unsuccessful lobbying attempt on behalf of his older brother. It was at this point (1893) that he accepted a year-long contract from an Indian firm to a post in KwaZulu-Natal Province (Natal), South Africa.

Civil rights movement in South Africa (1893–1914)

Gandhi, a young lawyer, was mild-mannered, diffident, and politically indifferent. He had read his first newspaper at the age of 18, and was prone to stage fright while speaking in court. The discrimination commonly directed at blacks and Indians in South Africa changed him dramatically. Two incidents are particularly notable. In court in the city of Durban, shortly after arriving in South Africa, Gandhi was asked by a magistrate to remove his turban. Gandhi refused, and subsequently stormed out of the courtroom. Not long after that he was thrown off a train at Pietermaritzburg for refusing to ride in the third-class compartment while holding a valid first-class ticket. Later, on the same journey, a stagecoach driver beat him for refusing to make room for a European passenger by standing on the footboard. Finally, he was barred from several hotels because of his race. This experience of racism, prejudice and injustice became a catalyst for his later activism. The moral indignation he felt led him to organize the Indian community to improve their situation.

At the end of his contract, preparing to return to India, Gandhi learned about a bill before the Natal Legislative Assembly that if passed, would deny Indians in South Africa the right to vote. His South African friends lamented that they could not oppose the bill because they did not have the necessary expertise. Gandhi stayed and thus began the “History of Satyagraha” in South Africa. He circulated petitions to the Natal Legislature and to the British Government opposing the bill. Though unable to halt the bill's passage, his campaign drew attention to the grievances of Indians in South Africa. Supporters convinced him to remain in Durban to continue fighting against the injustices they faced. Gandhi founded the Natal Indian Congress in 1894, with himself as the secretary and used this organization to mold the Indian community of South Africa into a heterogeneous political force. He published documents detailing their grievances along with evidence of British discrimination in South Africa.

In 1896, Gandhi returned briefly to India to bring his wife and children to live with him in South Africa. While in India he reported the discrimination faced by Indian residents in South Africa to the newspapers and politicians in India. An abbreviated form of his account found its way into the papers in Britain and finally in South Africa. As a result, when he returned to Natal in January 1897, a group of angry white South African residents were waiting to lynch him. His personal values were evident at that stage: he refused to press charges on any member of the group, stating that it was one of his principles not to seek redress for a personal wrong in a court of law.

Gandhi opposed the British policies in South Africa, but supported the government during the Boer War in 1899. Gandhi argued that support for the British legitimized Indian demands for citizenship rights as members of the British Empire. But his volunteer ambulance corps of three hundred free Indians and eight hundred indentured laborers (the Indian Ambulance Corps), unlike most other medical units, served wounded black South Africans. He was decorated for his work as stretcher-bearer during the Battle of Spion Kop. In 1901, he considered his work in South Africa to be done, and set up a trust fund for the Indian community with the farewell gifts given to him and his family. It took some convincing for his wife to agree to give up the gold necklace which according to Gandhi did not go with their new, simplified lifestyle. They returned to India, but promised to return if the need arose. In India Gandhi again informed the Indian Congress and other politicians about events in South Africa.

At the conclusion of the war the situation in South Africa deteriorated and Gandhi was called back in late 1902. In 1906, the Transvaal government required that members of the Indian community be registered with the government. At a mass protest meeting in Johannesburg, Gandhi, for the first time, called on his fellow Indians to defy the new law rather than resist it through violence. The adoption of this plan led to a seven-year struggle in which thousands of Indians were jailed (including Gandhi on many occasions), flogged, or even shot, for striking, refusing to register, burning their registration cards, or engaging in other forms of non-violent resistance. The public outcry over the harsh methods of the South African government in response to the peaceful Indian protesters finally forced South African General Jan Christian Smuts to negotiate a compromise with Gandhi.

This method of Satyagraha (devotion to the truth), or non-violent protest, grew out of his spiritual quest and his search for a better society. He came to respect all religions, incorporating the best qualities into his own thought. Instead of doctrine, the guide to his life was the inner voice that he found painful to ignore, and his sympathy and love for all people. Rather than hatred, he advocated helping the opponent realize their error through patience, sympathy and, if necessary, self-suffering. He often fasted in penance for the harm done by others. He was impressed with John Ruskin’s ideas of social reform (Unto This Last) and with Leo Tolstoy’s ideal of communal harmony (The Kingdom of God is Within You). He sought to emulate these ideals in his two communal farms—Phoenix Colony near Durban and Tolstoy Farm near Johannesburg. Residents grew their own food and everyone, regardless of caste, race or religion, was equal.

Gandhi published a popular weekly newspaper, Indian Opinion, from Phoenix, which gave him an outlet for his developing philosophy. He gave up his law practice. Devotion to community service had led him to a vow of brahmacharya in 1906. Thereafter, he denied himself worldly and fleshly pleasures, including rich food, sex (his wife agreed), family possessions, and the safety of an insurance policy. Striving for purity of thought, he later challenged himself against sexual arousal by close association with attractive women—an action severely criticized by modern Indian cynics who doubt his success in that area.

Fighting for Indian Independence (1916–1945)

Gandhi and his family returned to India in 1915, where he was called the “Great Soul (“Mahatma”) in beggar’s garb” by Rabindranath Tagore, the Bengali poet and public intellectual.[2] In May of the same year he founded the Satyagrah Ashram on the outskirts of Ahmedabad with 25 men and women who took vows of truth, celibacy, ahimsa, nonpossession, control of the palate, and service of the Indian people.

He sought to improve Hinduism by eliminating untouchability and other outdated customs. As he had done in South Africa, Gandhi urged support of the British during World War I and actively encouraged Indians to join the army, reasoning again that if Indians wanted full citizenship rights of the British Empire, they must help in its defense. His rationale was opposed by many. His involvement in Indian politics was mainly through conventions of the Indian National Congress, and his association with Gopal Krishna Gokhale, one of most respected leaders of the Congress Party at that time.

Champaran and Kheda

Gandhi first used his ideas of Satyagraha in India on a local level in 1918 in Champaran, a district in the state of Bihar, and in Kheda in the state of Gujarat. In both states he organized civil resistance on the part of tens of thousands of landless farmers and poor farmers with small lands, who were forced to grow indigo and other cash crops instead of the food crops necessary for their survival. It was an area of extreme poverty, unhygienic villages, rampant alcoholism and untouchables. In addition to the crop growing restrictions, the British had levied an oppressive tax. Gandhi’s solution was to establish an ashram (religious community) near Kheda, where scores of supporters and volunteers from the region did a detailed study of the villages—itemizing atrocities, suffering and degenerate living conditions. He led the villagers in a clean up movement, encouraging social reform, and building schools and hospitals.

For his efforts Gandhi was arrested by police on the charges of unrest and was ordered to leave Bihar. Hundreds of thousands of people protested and rallied outside the jail, police stations and courts demanding his release, which was unwillingly granted. Gandhi then organized protests and strikes against the landlords, who finally agreed to more pay and allowed the farmers to determine what crops to grow. The government cancelled tax collections until the famine ended. Gandhi’s associate, Sardar Vallabhai Patel, represented the farmers in negotiations with the British in Kheda, where revenue collection was suspended and prisoners were released. The success in these situations spread throughout the country. It was during this time that Gandhi began to be addressed as Bapu (“Father”) and Mahatma—the designation from Rabindranath Tagore.

Non-Cooperation

Gandhi used Satyagraha on a national level in 1919, the year the Rowlatt Act was passed, allowing the government to imprison persons accused of sedition without trial. Also that year, in Punjab, between one and two thousand people were wounded and four hundred or more were killed by British troops in the “Amritsar massacre.”[2] A traumatized and angry nation engaged in retaliatory acts of violence against the British.

Gandhi criticized both the British and the Indians. Arguing that all violence was evil and could not be justified, he convinced the national party to pass a resolution offering condolences to British victims and condemning the Indian riots.[3] At the same time, these incidents led Gandhi to focus on complete self-government and complete control of all government institutions. This matured into Swaraj or complete individual, spiritual, political independence.

In 1921, the Indian National Congress invested Gandhi with executive authority. Under his leadership, the party was transformed from an elite organization to one of mass national appeal and membership was opened to anyone who paid a token fee. Congress was reorganized (including a hierarchy of committees), got a new constitution and the goal of Swaraj. Gandhi’s platform included a swadeshi policy—the boycott of foreign-made (British) goods. Instead of foreign textiles, he advocated the use of khadi (homespun cloth), and spinning to be done by all Indian men and women, rich or poor, to support the independence movement.[4] Gandhi’s hope was that this would encourage discipline and dedication in the freedom movement and weed out the unwilling and ambitious. It was also a clever way to include women in political activities generally considered unsuitable for them. Gandhi had urged the boycott of all things British, including educational institutions, law courts, government employment, British titles and honours. He himself returned an award for distinguished humanitarian work he received in South Africa. Others renounced titles and honors, there were bonfires of foreign cloth, lawyers resigned, students left school, urban residents went to the villages to encourage non violent non-cooperation.[2]

This platform of "non-cooperation" enjoyed wide-spread appeal and success, increasing excitement and participation from all strata of Indian society. Yet just as the movement reached its apex, it ended abruptly as a result of a violent clash in the town of Chauri Chaura, Uttar Pradesh, in February 1922, resulting in the death of a policeman. Fearing that the movement would become violent, and convinced that his ideas were misunderstood, Gandhi called off the campaign of mass civil disobedience.[5] He was arrested on March 10, 1922, tried for sedition, and sentenced to six years in prison. After serving nearly two years, he was released (February 1924) after an operation for appendicitis.

Meanwhile, without Gandhi, the Indian National Congress had split into two factions. Chitta Ranjan Das and Motilal Nehru broke with the leadership of Chakravarti Rajagopalachari and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel in the National Congress Party to form the Swaraj Party. Furthermore, cooperation among Hindus and Muslims, which had been strong during the nonviolence campaign, was breaking down. Gandhi attempted to bridge these differences through many means, including a 21-day fast for Hindu-Muslim unity in the autumn of 1924, but with limited success.[6]

Swaraj and the Salt Satyagraha

For the next several years, Gandhi worked behind the scenes to resolve the differences between the Swaraj Party and the Indian National Congress. He also expanded his initiatives against untouchability, alcoholism, ignorance and poverty.

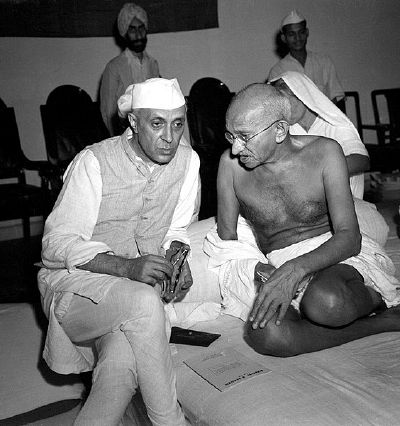

In 1927 a constitutional reform commission was appointed under Sir John Simon. Because it did not include a single Indian, it was successfully boycotted by both Indian political parties. A resolution was passed at the Calcutta Congress, December 1928, calling on Britain to grant India dominion status or face a new campaign of non-violence with complete independence as the goal. Indian politicians disagreed about how long to give the British. Younger leaders Subhas Chandra Bose and Jawaharlal Nehru called for immediate independence, whereas Gandhi wanted to allow two years. They settled on a one-year wait.[7]

In October, 1929, Lord Irwin revealed plans for a round table conference between the British and the Indian representatives, but when asked if its purpose was to establish dominion status for India, he would give no such assurances. The Indian politicians had their answer. On December 31, 1929, the flag of India was unfurled in Lahore. On January 26, 1930, millions of Indians pledged complete independence at Gandhi’s request. The day is still celebrated as India's Independence Day.

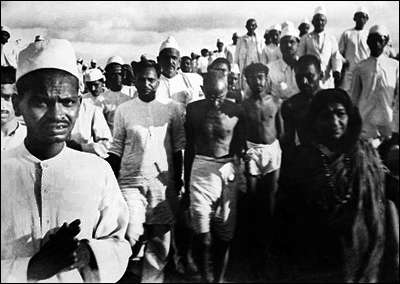

The first move in the Swaraj non-violent campaign was the famous Salt March. The government monopolized the salt trade, making it illegal for anyone else to produce it, even though it was readily available to those near the sea coast. Because the tax on salt affected everyone, it was a good focal point for protest. Gandhi marched 400 kilometers (248 miles) from Ahmedabad to Dandi, Gujarat to make his own salt near the sea. In the 23 days (March 12 to April 6) it took, the march gathered thousands. Once in Dandi, Gandhi encouraged everyone to make and trade salt. In the next days and weeks, thousands made or bought illegal salt, and by the end of the month, more than 60,000 had been arrested. It was one of his most successful campaigns, and as a result, Gandhi was arrested and imprisoned in May.

Recognizing his influence on the Indian people, the government, represented by Lord Irwin, decided to negotiate with Gandhi. The Gandhi-Irwin Pact, signed on March 1931, suspended the civil disobedience movement in return for freeing all political prisoners, including those from the salt march, and allowing salt production for personal use. As the sole representative of the Indian National Congress, Gandhi was invited to attend a Round Table Conference in London, but was disappointed to find it focused on Indian minorities (mainly Muslims) rather than the transfer of power.

Gandhi and the nationalists faced a new campaign of repression under Lord Irwin's successor, Lord Willingdon. Six days after returning from England, Gandhi was arrested and isolated from his followers in an unsuccessful attempt to destroy his influence. Meanwhile, the British government proposed segregation of the untouchables as a separate electorate. Gandhi objected, and embarked on a fast to death to procure a more equitable arrangement for the Harijans. On the sixth day of his fast, the government agreed to abandon the idea of a separate electorate. This began a campaign by Gandhi to improve the lives of the untouchables, whom he named Harijans, “the children of God.” On May 8, 1933 Gandhi began a 21-day fast of self-purification to help the Harijan movement.[8] In 1933 he started a weekly publication, The Harijan, through which he made public his thoughts to the Indian people all the rest of his life. In the summer of 1934, three unsuccessful attempts were made on his life. Visiting the cotton factory workers in the north of England, Gandhi found that he was a popular figure amongst the English working class even as he was reviled as that “seditious middle temple lawyer” as a “half-naked fakir” by Winston Churchill.

Gandhi resigned as leader and member from the Congress party in 1934, convinced that it had adopted his ideas of non-violence as a political strategy rather than a as a fundamental life principle. His resignation encouraged wider participation among communists, socialists, trade unionists, students, religious conservatives, persons with pro-business convictions.[9] He returned to head the party in 1936, in the Lucknow session of Congress with Nehru as president. Gandhi wanted the party to focus on winning independence, but he did not interfere when it voted to approve socialism as its goal in post-independence. But he clashed with Subhas Bose, who was elected president in 1938, and opposed Gandhi’s platforms of democracy and of non-violence. Despite their differences and Gandhi’s criticism, Bose won a second term, but left soon after when the All-India leaders resigned en masse in protest of his abandonment of principles introduced by Gandhi.[10]

World War II and “Quit India”

When World War II broke out in 1939, Gandhi was initially in favor of "non-violent moral support" for the British. Other Congress leaders, however, were offended that the viceroy had committed India in the war effort without consultation, and resigned en masse.[11] After lengthy deliberations, Indian politicians agreed to cooperate with the British government in exchange for complete independence. The viceroy refused, and Congress called on Gandhi to lead them. On August 8, 1942, Congress passed a “Quit India” resolution, which became the most important move in the struggle for independence. There were mass arrests and violence on an unprecedented scale.[12] Thousands of freedom fighters were killed or injured in police firing, and hundreds of thousands were arrested. Gandhi clarified that this time the movement would not be stopped if individual acts of violence were committed, saying that the "ordered anarchy" around him was "worse than real anarchy." He called on all Congressmen and Indians to maintain discipline in ahimsa, and Karo Ya Maro (“Do or Die”) in the cause of ultimate freedom.

Gandhi and the entire Congress Working Committee were arrested in Bombay (Mumbai) by the British on August 9, 1942. Gandhi was held for two years in the Aga Khan Palace in Pune. Although the ruthless suppression of the movement by British forces brought relative order to India by the end of 1943, Quit India succeeded in its objective. At the end of the war, the British gave clear indications that power would be transferred to Indian hands, and Gandhi called off the struggle, and the Congress leadership and around 100,000 political prisoners were released.

During his time in prison, Gandhi's health had deteriorated, however, and he suffered two terrible blows in his personal life. In February 1944, his wife Kasturba died in prison, and just a few months earlier Mahadev Desai, his 42-year old secretary, died of a heart attack. Six weeks after his wife’s death, Gandhi suffered a severe malaria attack. He was released before the end of the war because of his failing health and necessary surgery; the British did not want him to die in prison and enrage the entire nation beyond control.

Freedom and partition of India

In March 1946, the British Cabinet Mission recommended complete withdrawal of the British from India, and the formation of one federal Indian government. However, the Muslim League's “two nation” policy demanded a separate state for India's Muslims and it withdrew its support for the proposal. Gandhi was vehemently opposed to any plan that divided India into two separate countries. Muslims had lived side by side with Hindus and Sikhs for many years. However, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the League's leader, commanded widespread support in Punjab, Sindh, NWFP and East Bengal. Congress leaders, Nehru and Patel, both realized that control would go to the Muslim League if the Congress did not approve the plan. But they needed Gandhi’s agreement. Even his closest colleagues accepted partition as the best way out. A devastated Gandhi finally gave his assent, and the partition plan was approved by the Congress leadership as the only way to prevent a wide-scale Hindu-Muslim civil war.

Gandhi called partition “a spiritual tragedy.” On the day of the transfer of power (August 15, 1947), Gandhi mourned alone in Calcutta, where he had been working to end the city’s communal violence. When fresh violence broke out there a few weeks later, he vowed to fast to death unless the killing stopped. All parties pledged to stop. He also conducted extensive dialogue with Muslim and Hindu community leaders, working to cool passions in northern India, as well.

Despite the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947, he was troubled when the government decided to deny Pakistan the 550 million rupees (Rs. 55 crores) due as per agreements made by the Partition Council. Leaders like Sardar Patel feared that Pakistan would use the money to bankroll the war against India. Gandhi was also devastated when demands resurged for all Muslims to be deported to Pakistan, and when Muslim and Hindu leaders expressed frustration and an inability to come to terms with one another.[13] He launched his last fast-unto-death in Delhi, asking that all communal violence be ended once and for all, and that the full payment be made to Pakistan.

Gandhi feared that instability and insecurity in Pakistan would increase their anger against India, and violence would spread across the borders. He further feared that Hindus and Muslims would renew their enmity and precipitate into an open civil war. After emotional debates with his life-long colleagues, Gandhi refused to budge, and the government rescinded its policy and made the payment to Pakistan. Hindu, Muslim and Sikh community leaders, including the RSS and Hindu Mahasabha, assured him that they would renounce violence and call for peace. Gandhi thus broke his fast by sipping orange juice.[14]

Assassination

On January 30, 1948, on his way to a prayer meeting, Gandhi was shot dead in Birla House, New Delhi, by Nathuram Godse. Godse was a Hindu radical with links to the extremist Hindu Mahasabha, who held Gandhi responsible for weakening India by insisting upon a payment to Pakistan.[15] Godse and his co-conspirator Narayan Apte were later tried and convicted and were executed on November 15, 1949. A prominent revolutionary and Hindu extremist, the president of the Mahasabha, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was accused of being the architect of the plot, but was acquitted due to lack of evidence. Gandhi's memorial (or Samādhi) at Rāj Ghāt, Delhi, bears the epigraph, (Devanagiri: हे ! राम or, Hé Rām), which may be translated as "Oh God." These are widely believed to be Gandhi's last words after he was shot at, though the veracity of this statement has been disputed by many.[16] Jawaharlal Nehru addressed the nation through radio:

Friends and comrades, the light has gone out of our lives, and there is darkness everywhere, and I do not quite know what to tell you or how to say it. Our beloved leader, Bapu as we called him, the father of the nation, is no more. Perhaps I am wrong to say that; nevertheless, we will not see him again, as we have seen him for these many years, we will not run to him for advice or seek solace from him, and that is a terrible blow, not for me only, but for millions and millions in this country.

Gandhi's principles

Satyagraha

Gandhi is best known for his method of nonviolent resistance, the means to resist the unjust measures of a powerful superordinate. It was a method he developed while helping the Indian community in South Africa improve their situation in a country where discrimination was the rule, and a method the Indian people used under his guidance to win independence from the British. The term is a combination of two words: Satya or “truth” (including love), and agraha, or “firmness” (implying a force). For Gandhi it meant the force which is born of truth and love or non-violence. As Gandhi explains, because truth appears differently to different people, one can not use violence on one’s opponent, but rather should rather help them to understand that their view of truth is not correct. “He must be weaned from error by patience and sympathy. …And patience means self-suffering.”

For Gandhi, the satyagraha meant “vindication of truth” by self-suffering. In other words, if you have the strength of your convictions, you can afford to be patient and help your opponent realize a higher truth than the one they currently adhere to, even if it means that you will suffer in the process. It was a technique that he claims he learned from his wife, who patiently endured his erroneous ideas. The idea also grew out of his adherence to ahimsa, the non-harming of living things, and tapasya, the willingness to sacrifice oneself. He believed that ahimsa is the basis of a search for truth; that truth is the substance of morality, and that morality is the basis of all things.[17]

The profoundness of his method is seen in its practice. Gandhi was willing to sacrifice his life on many occasions, pledging to fast until death, giving him a spiritual power not often seen. His successful use of satyagraha stands as an example for anyone or any group facing discrimination and injustice. Other social reformers have been inspired by his ideas and successfully used them in their own struggles.

It is important to remember, however, that there are several things that satyagraha is not, as Gandhi himself pointed out. It is not a technique to be used to get one’s way, but a pursuit of truth with some points open to negotiation, according to the completeness of the parties’ understanding of truth. It will not be successful if used half-heartedly; because it is a life philosophy, and demands sincerity and willingness to sacrifice. It is not weakness; rather it can only be used in strength, requiring strength of conviction, strength to sacrifice, and strength to be patient.

At every meeting I repeated the warning that unless they felt that in non-violence they had come into possession of a force infinitely superior to the one they had and in the use of which they were adept, they should have nothing to do with non-violence and resume the arms they possessed before. It must never be said of the Khudai Khidmatgars that once so brave, they had become or been made cowards under Badshah Khan's influence. Their bravery consisted not in being good marksmen but in defying death and being ever ready to bear their breasts to the bullets.[18]

Service and Compassion

Although from a young age, Gandhi rejected the Hindu doctrine of untouchability; it was while he was in South Africa that publicly rejected the idea that anyone should be a servant or less privileged. In his Ashrams there was a rule that children would not be asked to do what the teachers would not do, and all residents washed the toilets—something that in India was the job of the untouchables. As stated in his autobiography and elsewhere, the service that was most satisfying to him was service of the poor.[19] His publication, Harijan—the affectionate name he gave to the untouchables—was his mouthpiece for the last 15 years of his life. Serving the poorest of the poor was Gandhi’s way of putting himself “last among his fellow creatures,” for those not willing to do so find no “salvation.”[20]

Although Gandhi hated the “evils” that he encountered, such as the system of the British in India, the exploitation of people anywhere it existed, and the Hindu custom of untouchability, he could not hate anyone, and believed it was wrong to slight them in any way, for to do so was to slight God, and “thus to harm not only that being but with him the whole world.”[21] Rather, he stated that he loved all people - as much as he loved those in India—“because God dwells in the heart of every human being, and I aspire to realize the highest in life through the service of humanity.”[22] But though he loved people everywhere, and thought the message of his life was universal, it could be delivered best through work in India.[23]

Although Gandhi thought that the British compromised their own principles by claiming to be champions of freedom, justice and democracy but denying these rights to India, he always hoped that Indians and the British would remain friends. Once asked what he thought of Western civilization, however, he famously replied that it “would be a good idea.”

Self-Restraint and Purity

Gandhi first discovered the “beauty of self-help” in South Africa when, out of economic interest, he began to wash and starch his own shirt collars, and to cut his own hair.[24] This progressed to simplicity in dress, possessions, and diet. At the age of 36, in 1906, he took a vow of brahmacharya, becoming totally celibate while still married. This decision was deeply influenced by the philosophy of spiritual and practical purity within Hinduism. He felt it his personal obligation to remain celibate so that he could learn to love, rather than lust, striving to maintain “control of the senses in thought, word and deed.” This practice of cultivating purity was his preparation for satyagraha and service to others. Gandhi felt his vow of sexual abstinence gave him a joy and freedom from “slavery to my own appetite” that he otherwise would not have known.[25]

For Gandhi self-restraint was necessary to meet God.[26] Diet was an important part of self-restraint, a first step in curbing animal passions and the desire for pleasure. He was vegetarian, but imposed upon himself further restrictions throughout his life, such as refraining from tea and eating after sunset—a custom he developed after serving time in South African prison in 1908. He also fasted as a means of developing the ability to surrender his body to God’s will rather than use it for self indulgence. But, he found, too much fasting could also be a kind of indulgence, so instead he sought other means of curbing his desire for the taste of food.[27]

As to possessions, once Gandhi devoted his life to service of others, he concluded that in order to remain moral and truthful and free from seeking personal gain, it was necessary to “discard all wealth, all possessions.” Further, he reasoned, if he had wealth and someone with a greater need stole from him, he could not fault them. In keeping with his philosophy of nonviolence, he concluded he should “not wish for anything on this earth which the meanest or lowest of human beings cannot have.”[28] As his possessions “slipped away,” he felt a burden was lifted from his shoulders. “I felt that I could now walk with ease and do my work in the service of my fellow men with great comfort and still greater joy.” In the end he concluded that by dispossessing himself of all his possessions, he came to “possess all the treasures of the world.”[29] He passionately wanted justice for all people; his “there is enough in the world for everyone's need but not for everyone's greed” powerfully sums up the truth that if some people had less, others would have enough.

Gandhi also practiced self-restraint in speech. He spent one day each week in silence, believing it brought him an inner peace. This influence was drawn from the Hindu principles of mouna (silence) and shanti (peace). On such days he communicated with others by writing on paper. He also practiced self-restraint in consumption of the news. For three and a half years, from the age of 37, he refused to read newspapers, claiming that the tumultuous state of world affairs caused him more confusion than his own inner unrest.

Religion

Gandhi saw religion in practical terms, and its meaning to him was as a means of “self-realization or knowledge of self.” During his time in England and South Africa, he studied the writings of all major religions and concluded that they were equal. He recognized that at the core of every religion was truth and love, and he thought the Bible and the Qur'an and other holy books were the inspired Word of God just as were the Vedas.

Later in his life, when he was asked whether he was a Hindu, he replied: "Yes I am. I am also a Christian, a Muslim, a Buddhist and a Jew." He enjoyed several long lasting friendships with Christians, including the Anglican celergyman Charles Freer Andrews (1871-1840), whom he called Deenabandhu (“friend of the poor”). However, he once said that it was Christians that put him off Christianity. He greatly admired Jesus. What mattered was not what people believed about Jesus but whether they lived and acted as Jesus had. “Action,” said Gandhi, “Is my domain.” He was bitterly opposed, however, to conversion—Gandhi once said that he would outlaw this if he had the power to do so.

It was in Pretoria, South Africa, that Gandhi became more religious. As he describes it, “the religious spirit within me became a living force.”[30] But though many tried to convince him to convert to another religion, it was Hinduism that “satisfies my soul, fills my whole being.” Still, he recognized that his own religion, like all others, contained hypocrisy and malpractice. He worked to reform what he saw as the flaws in the practice of Hinduism in India, including the caste system, the practice of satee and dowry.

He did not regard himself unusual in the things that he did in his life, insisting that anyone might do the same if they applied the same effort. He had no super power, and refused to let people in his ashram call him “Mahatma.” Rather, in his own estimation, he had a corruptible flesh, and was liable to err. Confession of error—a “broom that sweeps away dirt and leaves the surface cleaner”—is an important part of a truthful life.[31] He tolerated the world’s imperfections, he said, because he needed toleration and charity in return. He regarded his imperfections and failures as much of God’s blessing as his successes and talents.[32]

Criticism

Throughout his life and after his death, Gandhi has evoked serious criticism. B. R. Ambedkar, the Dalit political leader condemned Gandhi's term “Harijans” for the untouchable community as condescending. Ambedkar and his allies complained that Gandhi undermined Dalit political rights. Muhammad Ali Jinnah and contemporary Pakistanis often condemn Gandhi for undermining Muslim political rights. Vinayak Damodar Savarkar condemned Gandhi for appeasing Muslims politically; Savarkar and his allies blamed Gandhi for facilitating the creation of Pakistan and increasing the Muslim political influence. In contemporary times, historians like Ayesha Jalal blame Gandhi and the Congress for being unwilling to share power with Muslims and thus hastening partition. Hindu political extremists like Pravin Togadia and Narendra Modi sometimes criticize Gandhi's leadership and actions.

Gandhi believed that the mind of an oppressor or a bigot could be changed by love and non-violent rejection of wrong actions, while accepting full responsibility for the consequences of the actions. However, some modern critics, such as Penn and Teller, attack Gandhi for hypocrisy, inconsistent stands on nonviolence, inappropriate behavior with women and racist statements.

Gandhi has also been criticized by various historians and commentators for his attitudes regarding Hitler and Nazism. Gandhi thought that Hitler's hatred could be transformed by Jewish non-violent resistance, stating they should have willingly gone to their deaths as martyrs.[33][34]

At times his prescription of non-violence was at odds with common sense, as seen in a letter to the British people in 1940 regarding Hitler and Mussolini:

I want you to lay down the arms you have as being useless for saving you or humanity. You will invite Herr Hitler and Signor Mussolini to take what they want of the countries you call your possessions. Let them take possession of your beautiful island with your many beautiful buildings... If these gentlemen choose to occupy your homes, you will vacate them. If they do not give you free passage out, you will allow yourself, man, woman and child to be slaughtered... I am telling His Excellency the Viceroy that my services are at the disposal of His Majesty's government, should they consider them of any practical use in enhancing my appeal.[35]

Gandhi's ideal of cottage industry, self-sufficiency and a return to a traditional Indian lifestyle has been criticized by some as impractical. Jawaharlal Nehru, India's first prime minister, saw India's future as a modern, technologically developed nation and did not agree with Gandhi's vision. Although Gandhi had very little political influence on post-independence India, many of his criticized policies have become important to modern India. Self-sufficiency was pursued after independence in areas such as the steel industry in order to reduce dependence upon other countries for infrastructure materials. Cottage industry, especially arts and textiles, has been a way to encourage economic development among the villagers. The many years of socialist government under Mrs. Gandhi contributed to a shift from western to more simple, if not Indian values and dress. Some suggest that Britain left India because it could no longer afford to keep it. To what extent Gandhi's non-violent tactics and vision was a cause, an encouragement, or hardly relevant to Britain's actions is a continuing debate among historians and politicians.

Family

His own high standards were sometimes difficult for others to emulate, including his own family. Everyone in his ashram was expected to take turns cleaning out the latrine. Gandhi’s wife found this very demeaning, although she complied. His elder son had a difficult relationship with him, although all his children remained loyal. They have helped to preserve his legacy, as have his grandchildren. His second son, Manilal (1889-1956) especially took up his ethic and was imprisoned several times for protesting against unjust laws as an activist editor and writer. His son Arun (born 1934) founded the M. K. Gandhi Institute for Non-Violence in Memphis, Tennessee, dedicated to applying the principles of nonviolence locally and globally. Rajmohan Gandhi, son of Devdas, has served in the India Congress, has written widely on human rights and conflict resolution and has received several honorary degrees from universities around the world. He is much in demand as an international speaker, as is Gandhi’s granddaughter, Ela Gandhi (daughter of Manilal), who, born in South Africa, has served as an MP. She is the founder of the Gandhi Development Trust.

Legacy

Gandhi never received the Nobel Peace Prize, though he was nominated for it five times between 1937 and 1948. Decades later the Nobel Committee publicly declared its regret for the omission. The prize was not awarded in 1948, the year of Gandhi's death, on the grounds that "there was no suitable living candidate" that year, and when the Dalai Lama was awarded the Prize in 1989, the chairman of the committee said that this was "in part a tribute to the memory of Mahatma Gandhi."[36] After Gandhi's death, Albert Einstein said of Gandhi: "Generations to come will scarcely believe that such a one as this walked the earth in flesh and blood." He also once said, "I believe that Gandhi's views were the most enlightened of all the political men in our time. We should strive to do things in his spirit: not to use violence in fighting for our cause, but by non-participation in anything you believe is evil."

Time magazine named Gandhi as the runner-up to Albert Einstein as "Person of the Century" at the end of 1999, and named The Dalai Lama, Lech Wałęsa, Martin Luther King, Jr., Cesar Chavez, Aung San Suu Kyi, Benigno Aquino Jr., Desmond Tutu, and Nelson Mandela as Children of Gandhi and his spiritual heirs to the tradition of non-violence.

The government of India awards the annual Mahatma Gandhi Peace Prize to distinguished social workers, world leaders and citizens. Mandela, the leader of South Africa's struggle to eradicate racial discrimination and segregation, is a prominent non-Indian recipient of this honor. In 1996, the Government of India introduced the Mahatma Gandhi series of currency notes in Rupees 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 500 and 1,000 denomination.

The best-known artistic depiction of Gandhi’s life is the film Gandhi (1982), directed by Richard Attenborough, and starring Ben Kingsley. However, post-colonial scholars argue that it overplays Gandhi’s role and underplays other prominent figures in the anti-colonial struggle. Other films have been made about Gandhi, including The Making of the Mahatma (directed by Shyam Benegal and starring Rajat Kapur), Sardar (starring Anu Kapoor), and Hey Ram (made by Kamal Hasan). Other dramas explore the troubled relationship with his eldest son, and the rationale and circumstances of Gandhi’s murder.

There are several statues of Gandhi in the United Kingdom, most notably in Tavistock Square, London (near University College, London), and January 30 is commemorated as National Gandhi Remembrance Day. Stripped of his membership of the bar, he was posthumously re-instated. In the United States, there are statues of Gandhi outside the Ferry Building in San Francisco, California, Union Square Park in New York City, the Martin Luther King, Jr., National Historic Site in Atlanta, Georgia, and near the Indian Embassy in Washington, D.C. There is also a statue of Gandhi signifying support for human rights in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. Last, but not least, the city of Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, where Gandhi was ejected in 1893 from a first-class train, now has a statue of Gandhi.

Any evaluation of Gandhi's legacy should take cognizance of the fact that he was effectively a private citizen, since his leadership of the Indian National Congress did not constitute a public office as such. His achievements should not be judged or evaluated as if he were the elected leader of his nation, or even a high official within a religious establishment. He did what he did out of a deep sense of personal duty.

Notes

- ↑ M. Gandhi, All Men are Brothers (New York: Continuum, 1980, ISBN 0826400035), 54.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 “Gandhi's Life In 5000 Words,” M. K. Gandhi.org, Bombay Sarvodaya Mandal/Gandhi Book Centre. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ↑ Rajmohan Gandhi, Patel: A Life (Ahmedabad, India: Navajivan Pub. House, 2011, ISBN 978-8172291389), 82.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, 89.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, 105.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, 131.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, 172.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, 230-232.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, 246.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, 277-281.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, 283-286.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, 318.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, 462.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, 464-466.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, 472.

- ↑ Vinay Lal, “‘Hey Ram’: The Politics of Gandhi’s Last Words,” Humanscape 8(1) (January 2001): 34-38. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ↑ M. Gandhi, All Men are Brothers, 9.

- ↑ Joan V. Bondurant, Conquest of Violence: The Gandhian Philosophy of Conflict (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988 ISBN 069102281X), 139.

- ↑ M. Gandhi, 17.

- ↑ M. Gandhi, 35.

- ↑ M. Gandhi, 24; 27.

- ↑ M. Gandhi, 48.

- ↑ M. Gandhi, 36.

- ↑ M. Gandhi, An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments With Truth (Boston: Beacon Press, 1993, ISBN 0807059099), 177.

- ↑ M. Gandhi, All Men are Brothers, 26; 44.

- ↑ M. Gandhi, All Men are Brothers, 22.

- ↑ M. Gandhi, All Men are Brothers, 40; 27.

- ↑ M. Gandhi, All Men are Brothers, 83.

- ↑ M. Gandhi, All Men are Brothers, 40; 41.

- ↑ M. Gandhi, All Men are Brothers, 16.

- ↑ M. Gandhi, All Men are Brothers, 35.

- ↑ M. Gandhi, All Men are Brothers, 46.

- ↑ David Lewis Schaefer, What Did Gandhi Do? National Review (April 28, 2003). Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ↑ Richard Grenier, The Gandhi Nobody Knows (Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1983, ISBN 978-0840753793).

- ↑ From Stanley Wolpert, Jinnah of Pakistan (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984, ISBN 0195034120).

- ↑ Øyvind Tønnesson, “Mahatma Gandhi, the Missing Laureate,” Nobel Foundation (December 1, 1999). Retrieved June 16, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bondurant, Joan V. Conquest of Violence: The Gandhian Philosophy of Conflict. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988. ISBN 069102281X

- Chadha, Yogesh. Gandhi: A Life. New York: John Wiley, 1997. ISBN 0471243787

- Fischer, Louis (ed.). The Essential Gandhi: An Anthology of His Writings on His Life, Work, and Ideas. New York: Vintage Books, 2002. ISBN 1400030501

- Gandhi, Mohandas K. Gandhi: An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth. Boston: Beacon Press, 1993. ISBN 0807059099.

- Gandhi, M. All Men are Brothers. New York, NY: Continuum, 1980. ISBN 0826400035

- Gandhi, Rajmohan. Patel: A Life. Ahmedabad: Navajivan Pub. House, 2011. ISBN 978-8172291389

- Grenier, Richard. The Gandhi Nobody Knows. Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1983. ISBN 978-0840753793

- Rühe, Peter. Gandhi. London and New York: Phaidon, 2001. ISBN 071484103X

- Sofri, Gianni. Gandhi and India. New York: Interlink Publ., 1999. ISBN 1566562392

- Tolstoy, Leo. The Kingdom of God is Within You. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2006. ISBN 0486451380

- Wolpert, Stanley. Jinnah of Pakistan. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1984. ISBN 0195034120

External links

All links retrieved June 16, 2023.

- M.K. Gandhi Institute for Nonviolence

- Comprehensive Website by Gandhian Institutions-Bombay Sarvodaya Mandal & Gandhi Research Foundation

- The Gandhi Foundation

- Gandhi Information Center

- GandhiServe Foundation – Mahatma Gandhi Research and Media Service

- Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya Gandhi Museum & Library

- Mahatma Gandhi, the missing laureate – The Nobel Prize

- “Gandhi on Jews & Middle-East: A Non-Violent Look at Conflict & Violence” by Mohandas K. Gandhi

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.