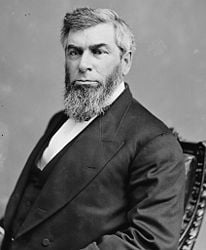

Morrison Waite

| Morrison Remick Waite | |

| |

7th Chief Justice of the United States

| |

| In office March 4, 1874 – March 23, 1888 | |

| Nominated by | Ulysses S. Grant |

|---|---|

| Preceded by | Salmon P. Chase |

| Succeeded by | Melville Fuller |

| Born | November 29, 1816 Lyme, Connecticut |

| Died | March 23, 1888 Washington, DC |

| Religion | Episcopalian |

Morrison Remick Waite (November 29, 1816 – March 23, 1888), nicknamed "Mott," was the Chief Justice of the United States from 1874 to 1888. Born in Connecticut, Waite attended Yale. After graduation, he moved to Ohio, where he was admitted to the bar in 1839, and in 1850, became recognized as a leader of the state bar. In 1849–1850, he was a Republican member of the Ohio Senate. Waite was a firm opponent of slavery. However, as Chief Justice, he ruled that blacks did not have a federal right of suffrage, because, "the right to vote comes from the states."

In the cases that grew out of the American Civil War and Reconstruction, Waite was sympathetic to the tendency of the court to restore states' rights and, in effect, to weaken the power of the Fourteenth Amendment and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

In 1876, when there was talk about a third term for President Grant, some Republicans turned to Waite who they preferred as a candidate over Grant. However, Waite turned down the offer, preferring to remain chief justice, a position he held until his death in 1888.

Early life and career

Waite was born at Lyme, Connecticut, the son of Henry Matson Waite, a judge of the Superior Court, associate judge of the Supreme Court of Connecticut, and its chief justice from 1854 to 1857.

Waite graduated from Yale University, where he was a classmate with the future Democratic presidential nominee, Samuel J. Tilden. There he became a member of the Skull and Bones Society in 1837, and soon after graduating, moved to Maumee, Ohio, where he studied law in the office of Samuel L. Young, and was admitted to the bar in 1839. He served one term as mayor of Maumee.

Waite married Amelia Warner in 1840, and had three sons with her—Henry Seldon, Christopher Champlin, Edward T.—and one daughter, Mary F.

In 1850, he moved to Toledo, and soon came to be recognized as a leader of the state bar. In politics, he was first a Whig and later a Republican. From 1849 to 1850, he was a member of the Ohio Senate.

Before the Civil War, Waite opposed both slavery and the southern slave states' withdrawal from the Union. In 1871, with William M. Evarts and Caleb Cushing, Waite represented the United States as counsel before the Alabama Tribunal at Geneva. In 1874, he presided over the Ohio constitutional convention.

In the same year, Waite was appointed by President Ulysses S. Grant to succeed Judge Salmon P. Chase as Chief Justice of the United States, and he held this position until his death in 1888. President Grant had offered the Chief Justiceship to, among others, Senator Roscoe Conkling and Democrat Caleb Cushing before he settled on Waite, who learned of his nomination by a telegram.

The nomination was not well-received. Former Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles remarked of the nomination that, "It is a wonder that Grant did not pick up some old acquaintance, who was a stage driver or bartender, for the place," and the political journal The Nation said "Mr. Waite stands in the front-rank of second-rank lawyers."

The Waite Court, 1874–1888

In the cases that grew out of the American Civil War and Reconstruction—and especially in those that involved the interpretation of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments—Waite sympathized with the general tendency of the court to restrict the further extension of the powers of the Federal government.

In a notable ruling in United States v. Cruikshank, he struck down the Enforcement Act, ruling that, "Sovereignty… rests alone with the States." He also stated that the Fifteenth Amendment could not confer the right to vote to blacks, because “the right to vote comes from the states."

His belief was that southern white moderates—not emancipated blacks or northern "carpetbaggers"—should set the rules of racial relations in the South, which reflected the majority of the Court and the people of the United States at the time, who were tired of the bitter racial strife involved with the affairs of Reconstruction. However, instead of strengthening the hands of moderates, his ruling enabled arch-segregationists to regain power and legislate the infamous Jim Crow laws that disenfranchised African-Americans in the South.

Waite's opinion of Munn v. Illinois (1877) was one of a group of six Granger cases involving Populist-inspired state legislation to fix maximum rates chargeable by grain elevators and railroads. Of it he wrote that when a business or private property was "affected with a public interest," it was subject to governmental regulation. Thus, he ruled against charges that Granger laws constituted encroachment of private property without due process of law. Later, ardent New Dealers in the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration looked to Munn v. Illinois to guide them in matters like due process, commerce, and contract clauses.

Among his other most important decisions were those in the Enforcement Act Cases (1875), the Sinking Fund Cases (1878), the Railroad Commission Cases (1886), and the Telephone Cases (1887).

Waite concurred with the majority in the Head Money Cases (1884), the Ku-Klux Case (United States v. Harris, 1883), the Civil Rights Cases (1883), Pace v. Alabama (1883), and the Legal Tender Cases, including Juillard v. Greenman (1883). In Reynolds v. United States (1878), Waite wrote that religious duty was not a suitable defense against a criminal indictment. Reynolds was a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, charged with bigamy in the Utah Territory.

Presidential run refused

In 1876, when there was talk about a third term for President Grant, some Republicans turned to Waite as they believed he was a better presidential nominee for the Republican Party than the scandal-tainted Grant. Waite turned down the idea, arguing "my duty was not to make it a stepping stone to someone else, but to preserve its purity and make my own name as honorable as that of any of my predecessors." In the aftermath of the presidential election of 1876, he refused to sit on the Electoral Commission that decided the electoral votes of Florida because of his close friendship of GOP presidential nominee Rutherford B. Hayes and his being a classmate at Yale with the Democratic presidential nominee Samuel J. Tilden. Waite served as chief justice for 14 years and died in Washington, D.C. on March 23, 1888, at the age of 71.

Legacy

Waite's legacy to constitutional law falls into three domains. His opinions were the first interpreting the Civil War Amendments. Second, his opinions guided state governments as they sought to address economic changes resulting from the industrial revolution. Finally, Waite's view of the judicial function guided thinking about judicial review well into the twentieth century.

Despite spending his entire career serving the legal rights of his fellow man, including being a firm opponent of slavery and a champion of the education of blacks in the South, some of Waite's court opinions empowering states' rights had the adverse effect of denying rights to the formerly enslaved.

As chief justice, Waite swore in Presidents Rutherford Hayes, James Garfield, Chester A. Arthur, and Grover Cleveland. Like his successor Melville Fuller, he is credited with being an efficient and capable administrator of the Court.

Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter said of him:

He did not confine the constitution within the limits of his own experience… The disciplined and disinterested lawyer in him transcended the bounds of the environment within which he moved and the views of the client whom he served at the bar.

Waite was one of the Peabody Trustees of Southern Education, and was a vocal advocate to aiding schools for the education of blacks in the south.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Magrath, C. Peter. Morrison R. Waite: The Triumph of Character. Macmillan, 1963.

- Rehnquist, William H. The Supreme Court. Vintage, 2002. ISBN 978-0375708619

- Stephenson, Donald and Peter Renstrom. The Waite Court: Justice, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO, 2003. ISBN 978-1576078297

- Trimble, Bruce R. Chief. Justice Waite: Defender of the Public Interest. Russell & Russell, 1970.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.