In general discussion, a nation-state is variously called a "country," a "nation," or a "state." But technically, it is a specific form of sovereign state (a political entity on a territory) that is guided by a nation (a cultural entity), and which derives its legitimacy from successfully serving all its citizens. The Compact OED defines "nation-state": a sovereign state of which most of the citizens or subjects are united also by factors which define a nation, such as language or common descent. The nation-state implies that a state and a nation coincide.

The modern state is relatively new to human history, emerging after the Renaissance and Reformation. It was given impetus by the throwing off of kings (for example, in the Netherlands and the United States) and the rise of efficient state bureaucracies that could govern large groups of people impersonally. Frederick the Great (Frederick II of Prussia 1740 - 1786) is frequently cited as one of the originators of modern state bureaucracy. It is based on the idea that the state can treat large numbers of people equally by efficient application of the law through the bureaucratic machinery of the state.

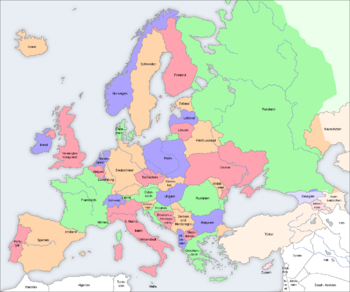

Some modern nation-states, for example in Europe or North America, prospered in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and were promoted as a model form of governance. The League of Nations (1919) and the United Nations are predicated on the concept of a community of nation-states. However, the concept of a modern nation-state is more an ideal than a reality. The majority of the world's people do not feel that the ruling elite in their state promotes their own national interest, but only that of the ruling party. As a result, most of the world's population does not feel their nation (cultural identity) is represented at the United Nations.

There are very few geographic territories in which a single ethnic, religious, or other culturally homogeneous group resides. This has been increasingly true as a result of globalization and the dispersion of people of countless national cultures all over the world displaced as refugees from national conflicts within states. The attempt to impose cultural homogeneity on all minority groups within a country has been one of the greatest scourges on human society, but it has taken on a particularly onerous quality in an increasingly pluralistic world. Genocides, civil wars, ethnic cleansing, and religious persecutions are rooted in the concept of creating a unified nation-state by force—a state in which a specific set of cultural norms are imposed either by the ruling elite, or by the majority.

Oppressed peoples have consistently risen up in self-defense to advocate freedom of religion, speech and cultural expression. Bloody revolutions, the arduous hardship of civil disobedience, the pressure for political reform from the mass media, outside campaigns by human rights organizations, and diplomatic efforts at high levels have been responses to the mistreatment of minorities in the modern state. Checks and balances on power, representation of all, equal opportunity, and equal protection all are ideals of the modern democratic and pluralistic state, which has these general values as its "national" culture while many sub-national minority groups remain free to exist. For example, a Mexican-American citizen of the United States gives his loyalty to the Constitution of the United States, obeys the laws of the state where he resides, while still being free to practice his inherited Mexican traditions, so long as they do not infringe upon the basic rights of others. While this balance of general national culture, or civil religion, and plural inherited national cultures is a requirement for social peace, it is an uneasy balance to maintain. This is a fundamental issue for world peace today.

The History of the Nation-state

The idea of a nation-state is associated with the rise of the modern system of states, usually dated to the Treaty of Westphalia (1648). The balance of power, which characterizes that system, depends for its effectiveness on clearly-defined, centrally controlled, independent powers, whether empires or nation-states. "The most important lesson that Hugo Grotius learned from the Thirty Years War (1618-1648), in the midst of which he wrote The Law of War and Peace, was that no single superpower can or should rule the world." Explaining the classical work of Grotius, Legal Scholar L. Ali Khan, in his book The Extinction of Nation-States (1996) traces the origin of the nation-states in the shared and universal human aspirations to "live in intimate communities free of all forms of foreign domination." Accordingly, some religious and secular empires were dismantled to make room for the emergence of the nation-state.[1] Nationalism requires a faith in the state and a loyalty to it. The nation-state received a philosophical underpinning from the era of Romanticism, at first as the "natural" expression of the individual peoples' romantic nationalism.[2] It developed into an absolute value in the philosophy of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. For him, the state was the final stage of march of the absolute in history,[3] taking on a near god-like quality.

The spread of the national idea was aided by developments of mass society, such as mass literacy and the mass media. Many feel the invention of the printing press made this possible, as it was with the widespread appeal of protestant reformation based on the printing of the Gutenberg Bible. Benedict Anderson has argued that nations form "imagined communities," and that the main causes of nationalism and the creation of an imagined community are the reduction of privileged access to particular script languages (e.g. Latin), the movement to abolish the ideas of divine rule and monarchy, as well as the emergence of the printing press under a system of capitalism (or, as Anderson calls it, 'print-capitalism'). Eric Hobsbawm argued that in France, however, the state preceded the formation of the nation. He said that nationalism emerged at the end of the nineteenth century around the Dreyfus Affair period. At the time of the 1789 French Revolution, only half of the French people spoke French, and between 12 to 13 percent spoke it "fairly." In Italy, the number of people speaking the Italian language was even lower.

The increasing emphasis on the ethnic and racial origins of the nation, during the nineteenth century, led to a redefinition of the nation-state in ethnic and racial terms. Racism, which in Boulainvilliers' theories was inherently anti-patriotic and anti-nationalist, joined itself with colonialist imperialism and "continental imperialism," most notably in pan-germanic and pan-slavism movements [4]. This relation between racism and nationalism attained its height in the fascist and Nazi movements of the twentieth century. The combination of 'nation' ('people') and 'state' expressed in such terms as the Völkische Staat and implemented in laws such as the 1935 Nuremberg laws made fascist states such as early Nazi Germany qualitatively different from non-fascist nation-states. This affected all minorities—not only Jews. Hannah Arendt points out how the Nazis had a law project that defined German nationality in exclusion to any foreign ascendancy, not just Jewish ascendancy. In the Nuremberg laws, those who are not part of the Volk, have no authentic or legitimate role in such a state.

The concept of an "ideal nation-state"

In the "ideal nation-state," the entire population of the territory pledges allegiance to the national culture. Thus, the population can be considered homogeneous on the state level, even if there is diversity at lower levels of social and political organization. The state not only houses the nation, but protects it and its national identity. Every member of the nation is a permanent resident of the nation-state, and no member of the nation permanently resides outside it. There are no pure nation-states, but examples that come close might include Japan and Iceland. This ideal, which grew out of feudal states, has influenced almost all existing modern states, and they cannot be understood without reference to that model. Thus, the term nation-state traditionally has been used, imprecisely, for a state that attempts to promote a single national identity, often beginning with a single national language, government, and economic system.

The modern nation-state is larger and more populous than the "city-states" of ancient Greece or Medieval Europe. Those "states" were governed through face-to-face relationships of people that often lived within the walls of the city. The nation-state also differs from an empire, which is usually an expansive territory comprising numerous states and many nationalities which is united by political and military power, and a common currency. The language of an empire is often not the mother tongue of most of its inhabitants.

The Formation of the Nation-State

The nation-state became the standard ideal in France during the French Revolution, and quickly the nationalist idea spread through Europe, and later the rest of the world. However island nations such as the English (and later British) or the Japanese tended to acquire a nation-state sooner than this, not intentionally (on the French revolutionary model) but by chance, because the island situation made the clear natural limits of state and nation coincide.

There are two directions for the formation of a nation-state. The first—and more peaceful way—is for responsible people living in a territory to organize a common government for the nation-state they will create. The second, and more violent and oppressive method—is for a ruler or army to conquer a territory and impose its will on the people it rules. Unfortunately, history has more frequently seen the latter method of nation-state formation.

From Nation(s) to Nation-State

In the first case a common national identity is developed among the peoples of a geographical territory and they organize a state based on their common identity. Two examples are the formation of the Dutch Republic and the United States of America.

The Dutch Republic

One of the earliest examples of the formation of such a nation-state was the Dutch Republic (1581 and 1795). The Eighty Years' War that began in 1568, triggered a process of what we might now call "nation-building." The following chain of events occurred in this process:

- The Dutch rebelled against Habsburg Spain, the largest and most powerful empire at that time. This created a "standing alone together" mentality that served as the initial basis for national identity (a common enemy).

- William I of Orange, a man of the people and a man of noble birth, served as a charismatic and emblematic leader of the Dutch people throughout the Eighty Years War even though he died in the middle of the war and did not literally found the nation. Yet, he is regarded as the Father of the Nation in the Netherlands.

- Protestantism was the dominant Dutch religion at that time, and they fought against a Catholic empire under the ruler Phillip II. This created both, another common enemy, a common Protestant worldview, and respect for religious freedom.

- The Dutch had their own language, which is considered one of the most important parts of a nation-state.

- The war was very cruel compared to other wars of that era, especially with the Spanish religious persecutions, and assaults on civilians as reprisals for the constant guerrilla attacks by the Dutch. This was the source of a common hate for the enemy, and stimulated a common sense of destiny that strengthened "national" feelings.

When the war had finally ended, with a complete Dutch victory, the Dutch could not find a king for their country, essential in the sixteenth-century Europe. After asking (and practically begging) a large number of royal families, it was decided that the Dutch nation should govern itself in the form of a republic. During this time, the Dutch Republic became a world superpower, launching a golden age in which the Dutch people made many discoveries and inventions, and conquered vast areas of the globe. This made the Dutch people feel they were a special people, another feature of nineteenth-century nationalism.

The United States of America

Another common example of government "of, by, and for the people" is the United States. A form of "nation-building" was also going on in the British Colonies in North America.

- Although the thirteen colonies were composed of as many "national" cultures, commerce and migration among and within the colonies created the sense of an American culture. For example, Benjamin Franklin published and distributed a newspaper throughout the colonies, and roads and a postal system helped increase exchange of products, people and ideas among the colonies.

- In the early part of the century the colonists generally felt they were British citizens. In 1754 Benjamin Franklin traveled to the Albany Congress and defended a plan for a political union of colonies.[5][6]

- During the last half of the eighteenth century, the British crown increasingly taxed the colonies, and British companies—like the British East India Company—exercised financial monopolies on commodities like tea, which placed economic hardships on merchants and entrepreneurs in the colonies. Protestant religious leaders, many of whom were trying to build their version of "the Kingdom of God" in America, increasingly preached loyalty to no king but God or "King Jesus." The Stamp Act, the Boston Tea Party, and the Boston "massacre" set in motion the revolution against the British Empire, the most powerful empire in its day.

- Eventually nearly all Americans joined the cause for independence, and with the aid of France (which was threatened by the growing power of England), succeeded in throwing off British oppression.

- The leadership, charisma, and dedication of revolutionary leaders like George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin prevailed in the creation of a Constitution for the new nation, despite the bickering and selfishness common in the nearly anarchic and bankrupt government under the Articles of Confederation. The general government the founders created guaranteed separation of church and state, freedom of the press, the right to bear arms, and the protection of private property. It was a general enough agreement that all subnationalities (except slaves) within the new nation could feel they were able to pursue life, liberty and happiness in their own way.

Like the Dutch Republic, the United States became a world superpower, launching a golden age in which people made many discoveries and inventions, and influenced vast areas of the globe. This made the American people feel they were a special people, a feature of nationalism.

From State to Nation-State

| Border of Austria-Hungary in 1914 |

| Borders in 1914 |

| Borders in 1920 |

In most cases, states exist on a territory that was conquered and controlled by monarchs possessing great armies. In eighteenth-century Europe, the classic non-national states were the multi-ethnic empires (Austria-Hungary, Russia, the Ottoman Empire, etc.), and the sub-national micro-state, e.g., a city-state or the Duchy.

Many leaders of modern states or empires have recognized the importance of national identity for legitimacy and citizen loyalty. As a result they have attempted to fabricate nationality or impose it from the top down. For example, Stalin reportedly said, "If we call it a Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, people will eventually believe it." Historians Benedict Anderson and the communist author Eric Hobsbawm have pointed out that the existence of a state often precedes nationalism. For example, French nationalism emerged in the nineteenth century, after the French nation-state was already constituted through the unification of various dialects and languages into the French language, and also by the means of conscription and the Third Republic's 1880s laws on public instruction.

Frederick the Great (1712–1786) expanded Prussia from obscurity among fellow nations to become foremost military power in Europe. He also laid the foundation for the eventual union of the German princely states, which would enable Germany to emerge as a major world power at the start of the twentieth century. Frederick's bureaucratic reforms made the Prussian civil service more efficient, methodical and hard working and also conscious of its public duty. He also introduced a system of primary education, and codified the law. This would become the basis of the future German state, and Prussian identity, which valued military prowess, owed a lot to Frederick's own military successes. This later became linked with the German sense of national superiority and of imperial destiny that contributed significantly to the causes of the two world wars.

Another example of the attempt to create a nation-state from above is colonial states in which occupying powers have drawn boundaries across the territories inhabited by various tribal and ethnic groups and imposing rule over this state. Most recently is the example of how the United States' occupation of Iraq, which displaced Saddam Hussein's empire (an empire because it was a multi-national territory held together by force), attempted to create a democratic nation-state where no significant national culture existed among the sub-national groups living on the territory.

Some states have developed genuine national identities over time because of the common shared experience of the citizens and reforms that have given all citizens representation.

Maintaining a Nation-State

Maintaining a peaceful nation-state requires ongoing legitimation of both the national ideas and norms and the state regime in the eyes of the citizens. This means that both the national ideas and government must be able to change and adapt to new circumstances, such as new developments in science and technology, economic conditions, new ideas, and demographic changes such as immigration. Historically, all states have had majority and minority religious, racial, and ethnic groups—and the larger the state, the more diversity is likely to exist.

Religion and the Nation-State

Religion is a primary component of most cultures, and many homogeneous peoples have tried to create nation-states with a state religion. In the West, this idea dates to the Roman Emperor Constantine I who made Christianity the official religion of the empire in an attempt to bring social stability. In 392 C.E., all other "pagan" cults were forbidden by an edict of Emperor Theodosius I.[7] Islam followed the same pattern with the concept of Dar-el-Haarb, which is a non-Muslim territory and the Dar-el-Islam, which is a Muslim territory.

The concept of an official state religion is similar to that of a nation-state, in that law enforces the moral norms and traditions of a people. This has worked reasonably well in some states where there is a relatively homogeneous population that believes that official religion is true and legitimate. However, like any social institution governed by law, state religions tend not to be able to change or adapt well to new ideas or circumstances. Their dogmas often become obsolete, and the attempt to force people to believe obsolete dogmas is oppressive. This pattern of official state religion has led to a history of repression of thought, thwarted scientific advancement, and pogroms (large, violent attacks on a religious or cultural group). In the West, this period has been terms the Dark Ages. Heretics were burned at the stake, books were burned, and entire towns destroyed in an attempt to keep religion pure. It took the church three hundred years to accept Nicolaus Copernicus' notion that the world was round. A similar phenomenon occurs in Islamic countries, especially those in which clerics (Imams) have the most power. The most extreme recent example being the Taliban in Afghanistan, where females were denied education in schools.

In Europe, the Reformation continued this pattern where rulers of a state would adopt a single official state religion. For example, England became Anglican, some German states became Reformed, and most of Scandinavia became Lutheran. Some of these smaller religiously homogeneous Protestant states continued to execute heretics and witches (like the Salem witch trials).

The Netherlands and the United States broke with this pattern with the implementation of religious freedom at the state level. It was a necessity when people were building a nation from the bottom up. One unexpected consequence of religious freedom was that voluntary acceptance of religion required doctrines that people considered legitimate. Competition for followers created religious fervor and creativity that far exceeded that in state churches. So, in the twentieth century church attendance grew dramatically in the United States and declined dramatically in Scandinavia. In the modern pluralistic world, freedom of religion is a necessity if minorities are to have equal rights in a nation-state.

National minorities and irredentism

Existing nation-states differ from the ideal as defined above in two main ways: the population includes minorities, and the border does not include the entire national group or its territory. Both have led to violent responses by nation-states, and nationalist movements. The nationalist definition of a nation is always exclusive: no nation has open membership. In most cases, there is a clear idea that surrounding nations are different. There are also historical examples of groups within the nation-state's territory who are specifically singled out as outsiders.

Negative responses to minorities dwelling within the nation-state have ranged from assimilation, expulsion, to extermination. Typically these responses are affected as state policy, though non-state violence in the form of mob violence such as lynching has often taken place. Many nation-states accept specific minorities as being in some way part of the nation, and the term national minority is often used in this sense. However, they are not usually treated as equal citizens.

The response to the non-inclusion of territory and population may take the form of irredentism, demands to annex unredeemed territory and incorporate it into the evolving nation-state, as part of the national homeland. Irredentist claims are usually based on the fact that an identifiable part of the national group lives across the border, in another nation-state. However, they can include claims to territory where no members of that nation live at present, either because they lived there in the past, or because the national language is spoken in that region, or because the national culture has influenced it, or because of geographical unity with the existing territory, or for a wide variety of other reasons. Past grievances are usually involved (see Revanchism). It is sometimes difficult to distinguish irredentism from pan-nationalism, since both claim that all members of an ethnic and cultural nation belong in one specific state. Pan-nationalism is less likely to ethnically specify the nation. For instance, variants of Pan-Germanism has different ideas about what constituted Greater Germany, including the confusing term Grossdeutschland—which in fact implied the inclusion of huge Slavic minorities from the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Typically, irredentist demands are at first made by members of non-state nationalist movements. When they are adopted by a state, they result in tensions, and actual attempts at annexation are always considered a casus belli, a cause for war. In many cases, such claims result in long-term hostile relations between neighboring states. Irredentist movements typically circulate maps of the claimed national territory, the greater nation-state. That territory, which is often much larger than the existing state, plays a central role in their propaganda.

Irredentism should not be confused with claims to overseas colonies, which are not generally considered part of the national homeland. Some French overseas colonies would be an exception: French rule in Algeria did indeed treat the colony legally as a département of France, unsuccessfully. The U.S. was more successful in Hawaii.

Conflicting national claims on territory

Nearly every nation can look back to a "golden age" in its past that included more territory than it occupies today. Some national groups, like the Kurds, currently have no sovereign territory, but logically could claim land that falls within the jurisdictions of present day Iraq, Turkey, and Iran. In most nation-states, all or part of the territory is claimed on behalf of more than one nation, by more than one nationalist movement. The intensity of the claims varies: some are no more than a suggestion, while others are backed by armed secessionist groups. Belgium is a classic example of a disputed nation-state. The state was formed by secession from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1830, and the Flemish population in the north speaks Dutch. The Flemish identity is also ethnic and cultural, and there is a strong separatist movement. The Walloon identity is linguistic (French-speaking) and regionalist. There is also a unitary Belgian nationalism, several versions of a Greater Netherlands ideal, and a German-speaking region annexed from Prussia in 1920, and re-annexed by Germany in 1940-1944.

If large sections of the population reject the national identity of the state, the legitimacy of the state is undermined, and the efficiency of government is reduced. That is certainly the case in Belgium, where the inter-communal tensions dominate politics.

Most states still declare themselves to be "nation-states," that is, states that attempt to define and enforce a state-sponsored national identity. In the case of very large states, there are many competing claims and often many separatist movements. These movements usually dispute that the larger state is a real nation-state, and refer to it as an empire and what is called nation-building is actually empire-building. There is no objective standard for assessing which claim is correct, they are competing political claims. Large nation-states have to define the nation on a broad basis. China, for example, uses the concept of "Zhonghua minzu," a Chinese people, although it also officially recognizes the majority Han ethnic group, and no less than 55 national minorities.

The Future of the Nation-State

In recent years, the nation-state's claim to absolute sovereignty within its borders has been increasingly criticized, especially where minorities do not feel the ruling elite represent their interests. Civil war and genocide among and between national groups within states has led to numerous demands that the United Nations abandon its charter, which holds state sovereignty sacred, and send in peace-keeping troops to resolve internal conflicts. These demands escalated after the collapse of the Soviet Union brought the end of the bi-polar world order beginning in the 1990s.

A global political system based on international agreements, and supranational blocs characterized the post-war era. Non-state actors, such as international corporations and trans-national non-governmental organizations, are widely seen as eroding the economic and political power of the nation-states. Some think this erosion will result in the extinction of the nation-state.[8]

The Corporation and the Nation-State

The "ideal nation-state" failed to consider the rise of the modern corporation, which is a more recent phenomenon than the nation-state itself. The freedom for economic development provided for in many nation-states—where the economy was no longer controlled by a royal family—helped the rise of modern corporations.

Power in the modern world is not dependent upon control of land territory, as in earlier times, but control of economic wealth that, in the twenty-first century, can freely move around the globe. The size of many economic corporations dwarfs many nation-states.[9] Increasingly corporations can buy armies and politicians in an attempt to make a state their servant. Many worry that "corporatocracy" or oligarchy is replacing, or will soon replace, democracy.

In the United States, for example, no large corporations existed at the time of the founding. The economy was based on subsistence farms and family businesses. It was not until the advent of the railroad and the Civil War in the middle of the nineteenth century that large industrial corporations began to develop. Initially the nation was funded by tariffs on imports, which gave U.S. corporations protection from competition by products from other countries. However, as corporations began to outproduce domestic consumption before the turn of the twentieth century, they sought to eliminate tariffs and will replace tariffs with an income tax. The United States built a navy to help U.S. products reach global markets. More recently, many large corporations have left the United States and relocated in countries where they can produce goods cheaper or pay lower taxes—effectively abandoning the mother that raised them. This same process has taken place in many countries, like South Korea and Japan.

Today society is divided into three main sectors; government, commerce, and culture. The nation is only one third of the equation. States will need to learn how to properly balance these three sectors.

The Failed state

Increasingly the term "failed state" is being used. Initially, this term was used more in reference to bankrupt states that could not pay international loans from the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund. This was a common plight for Latin American and African states in the 1980s and 1990s.

However, the term “failed state” is more commonly also being used to refer to states that fail to keep general order. This could be a state like Rwanda that disintegrates into civil war and genocide because as large national group (in this case the Hutus) feel that the controlling national group (Tutsis) it is not legitimate because it treats other groups unfairly.

With the advent of globalization in the twenty-first century, nations that cannot control the flow of international arms and provide a haven for terrorists plotting attacks elsewhere are considered failed states because they cannot control the people within their borders. Missile attacks from within a state on a neighboring state are considered acts of war by the victim state, even if the official government of the attacking state condemns the actions. In this case the neighboring state considers the regime to be illegitimate because it cannot control people living in its borders.

Much of the failure to keep order in modern states is based on the fact that many national groups are competing to control the same state. Those minorities who do not feel they have an adequate voice in the government, or feel they are not being given equal treatment, do not see the government as legitimate and may become a destabilizing force that leads to the failure of the state.

The End of the Nation-State?

More scholars are beginning to predict the end of the nation-state as an ideal. The idea of a sovereign state has already been abandoned by all but the most powerful countries. Increasingly, states are willing to accept regional-level government like the European Union for many government functions like producing money and regulation of commerce and trade. Regional courts of arbitration are increasingly accepted by traditional states that give up a measure of sovereignty for equal treatment and participation in a global community.

National and cultural groups will not disappear, as human beings are cultural and literary beings; however, the natural place for such groups is not the control of government resources in order to attain power and wealth at the expense of other groups. As people from different minority backgrounds continue to relocate and live in states that are not their ancestral home, pluralism will have to be accommodated for the sake of peace.

Pluralistic states, like those in the United States and the European Union, can agree on several general principles, such as murder, theft and rape are wrong and should be punished, while avoiding taking positions on divisive issues that exist in religious or ideological dogmas. No racial, ethnic, or religious group should be favored at the expense of others by a state, whose function is not naturally related national culture, but more naturally related to the governance of territorial functions like military protection, domestic security, physical infrastructure, inter-state water distribution, and the regulation of money. For these reasons, states will not disappear, even though they may become uncoupled from the ideal of a nation-state.

See also

- State

- City-state

- Nation

- Nationalism

- Colonialism

Notes

- ↑ L. Ali Khan, The Extinction of Nation-States-A World without Borders Reports in International Law, 22. (Leiden: Brill, 1996, ISBN 9041101985).

- ↑ See Johann Gottlieb Fichte's conception of the Volk, which would be later opposed by Ernest Renan.

- ↑ Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, The Philosophy of History (New York: Dover Publications, 1956), 412-457.

- ↑ See Hannah Arendt. The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951).

- ↑ Bernard Fay, Revolution and Freemasonry, 1680-1800 (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Co., 1935).

- ↑ Madison C. Peters, Masons as Makers of America (Brooklyn, NY: The Patriotic League, 1917).

- ↑ Gordon L. Anderson, Philosophy of the United States: Life Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness. (St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2004, ISBN 1557788448), 37 ff.

- ↑ Dave Carter, Review The Extinction of Nation-States by L. Ali Khan. EJIL.org.

- ↑ Fred Maidment, "Who's Big: The Top 100." International Journal on World Peace 19 (1) (March 2002): 67-74.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. New York, NY: Verso Books, 2006. ISBN 1844670864

- Anderson, Gordon L. Philosophy of the United States: Life Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 2004. ISBN 1557788448

- Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Schocken, 2004. ISBN 0805242252

- Fay, Bernard. Revolution and Freemasonry, 1680-1800. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Co., 1935.

- Fichte, Johann Gottlieb. Addresses to the German Nation. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1979. ISBN 0313212074

- Gellner, Ernest. Nations and Nationalism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1983. ISBN 0801492637

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. The Philosophy of History. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1956.

- Hobsbawm, E. J. Nations and Nationalism since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Khan, L. Ali. The Extinction of Nation-States: A World Without Borders. Leiden: Brill, 1996. ISBN 9041101985

- Peters, Madison C. Masons as Makers of America. Brooklyn, NY: The Patriotic League, 1917.

- Renan, Ernest. Wikisource: Qu'est-ce qu'une nation? 1882. (in French)

- Sassen, Saskia. Global Cities. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001. ISBN 0691070636

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.