Civil disobedience encompasses the active refusal to obey certain laws, demands, and commands of a government or of an occupying power without resorting to physical violence. Based on the position that laws can be unjust, and that there are human rights that supersede such laws, civil disobedience developed in an effort to achieve social change when all channels of negotiation failed. The act of civil disobedience involves the breaking of a law, and as such is a crime and the participants expect and are willing to suffer punishment in order to make their case known.

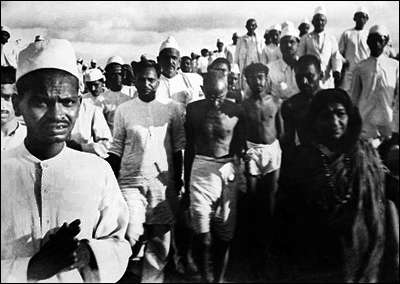

Civil disobedience has been used successfully in nonviolent resistance movements in India (Mahatma Gandhi's social welfare campaigns and campaigns to speed up independence from the British Empire), in South Africa in the fight against apartheid, and in the American Civil Rights Movement, among others. Until all people live under conditions in which their human rights are fully met, and there is prosperity and happiness for all, civil disobedience may be necessary to accomplish those goals.

Definition

The American author Henry David Thoreau pioneered the modern theory behind the practice of civil disobedience in his 1849 essay, Civil Disobedience, originally titled Resistance to Civil Government. The driving idea behind the essay was that of self-reliance, and how one is in morally good standing as long as one can "get off another man's back;" so one doesn't have to physically fight the government, but one must not support it or have it support one (if one is against it). This essay has had a wide influence on many later practitioners of civil disobedience. Thoreau explained his reasons for having refused to pay taxes as an act of protest against slavery and against the Mexican-American War.

Civil disobedience can be distinguished from other active forms of protest, such as rioting, because of its passivity and non-violence.

Theories and techniques

In seeking an active form of civil disobedience, one may choose to deliberately break certain laws, such as by forming a peaceful blockade or occupying a facility illegally. Protesters practice this non-violent form of civil disorder with the expectation that they will be arrested, or even attacked or beaten by the authorities. Protesters often undergo training in advance on how to react to arrest or to attack, so that they will do so in a manner that quietly or limply resists without threatening the authorities.

For example, Mahatma Gandhi outlined the following rules:

- A civil resister (or satyagrahi) will harbor no anger

- He will suffer the anger of the opponent

- In so doing he will put up with assaults from the opponent, never retaliate; but he will not submit, out of fear of punishment or the like, to any order given in anger

- When any person in authority seeks to arrest a civil resister, he will voluntarily submit to the arrest, and he will not resist the attachment or removal of his own property, if any, when it is sought to be confiscated by authorities

- If a civil resister has any property in his possession as a trustee, he will refuse to surrender it, even though in defending it he might lose his life. He will, however, never retaliate

- Retaliation includes swearing and cursing

- Therefore a civil resister will never insult his opponent, and therefore also not take part in many of the newly coined cries which are contrary to the spirit of ahimsa

- A civil resister will not salute the Union Jack, nor will he insult it or officials, English or Indian

- In the course of the struggle if anyone insults an official or commits an assault upon him, a civil resister will protect such official or officials from the insult or attack even at the risk of his life

Gandhi distinguished between his idea of satyagraha and the passive resistance of the west. Gandhi's rules were specific to the Indian independence movement, but many of the ideas are used by those practicing civil disobedience around the world. The most general principle on which civil disobedience rests is non-violence and passivity, as protesters refuse to retaliate or take action.

The writings of Leo Tolstoy were influential on Gandhi. Aside from his literature, Tolstoy was famous for advocating pacifism as a method of social reform. Tolstoy himself was influenced by the Sermon on the Mount, in which Jesus tells his followers to turn the other cheek when attacked. Tolstoy's philosophy is outlined in his work, Kingdom of God is Within You.

Many who practice civil disobedience do so out of religious faith, and clergy often participate in or lead actions of civil disobedience. A notable example is Philip Berrigan, a Roman Catholic priest who was arrested dozens of times in acts of civil disobedience in antiwar protests.

Philosophy of civil disobedience

The practice of civil disobedience comes into conflict with the laws of the country in which it takes place. Advocates of civil disobedience must strike a balance between obeying these laws and fighting for their beliefs without creating a society of anarchy. Immanuel Kant developed the "categorical imperative" in which every person's action should be just so that it could be taken to be a universal law. In civil disobedience, if every person were to act that way, there is the danger that anarchy would result.

Therefore, those practicing civil disobedience do so when no other recourse is available, often regarding the law to be broken as contravening a higher principle, one that falls within the categorical imperative. Knowing that breaking the law is a criminal act, and therefore that punishment will ensue, civil disobedience marks the law as unjust and the lawbreaker as willing to suffer in order that justice may ensue for others.

Within the framework of democracy, ideally rule by the people, debate exists over whether or not practices such as civil disobedience are in fact not illegal because they are legitimate expressions of the people's discontent. When the incumbent government breaks the existing social contract, some would argue that citizens are fully justified in rebelling against it as the government is not fulfilling the citizens' needs. Thus, one might consider civil disobedience validated when legislation enacted by the government is in violation of natural law.

The principle of civil disobedience is recognized as justified, even required, under exceptional circumstance such as war crimes. In the Nuremberg Trials following World War II, individuals were held accountable for their failure to resist laws that caused extreme suffering to innocent people.

Examples of civil disobedience

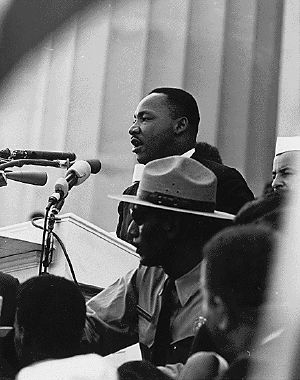

Civil disobedience in was used to great effect in India by Gandhi, in Poland by the Solidarity movement against Communism, in South Africa against apartheid, and in the United States by Martin Luther King, Jr. against racism. It was also used as a major tactic of nationalist movements in former colonies in Africa and Asia prior to their gaining independence.

India

Gandhi first used his ideas of Satyagraha in India on a local level in 1918, in Champaran, a district in the state of Bihar, and in Kheda in the state of Gujarat. In response to poverty, scant resources, the social evils of alcoholism and untouchability, and overall British indifference and hegemony, Gandhi proposed satyagraha—non-violent, mass civil disobedience. While it was strictly non-violent, Gandhi was proposing real action, a real revolt that the oppressed peoples of India were dying to undertake.

Gandhi insisted that the protesters neither allude to or try to propagate the concept of Swaraj, or Independence. The action was not about political freedom, but a revolt against abject tyranny amidst a terrible humanitarian disaster. While accepting participants and help from other parts of India, Gandhi insisted that no other district or province revolt against the government, and that the Indian National Congress not get involved apart from issuing resolutions of support, to prevent the British from giving it cause to use extensive suppressive measures and brand the revolts as treason.

In both states, Gandhi organized civil resistance on the part of tens of thousands of landless farmers and poor farmers with small lands, who were forced to grow indigo and other cash crops instead of the food crops necessary for their survival. It was an area of extreme poverty, unhygienic villages, rampant alcoholism and untouchables. In addition to the crop-growing restrictions, the British had levied an oppressive tax. Gandhi’s solution was to establish an ashram near Kheda, where scores of supporters and volunteers from the region did a detailed study of the villages—itemizing atrocities, suffering, and degenerate living conditions. He led the villagers in a clean up movement, encouraging social reform, and building schools and hospitals.

For his efforts, Gandhi was arrested by police on the charges of unrest and was ordered to leave Bihar. Hundreds of thousands of people protested and rallied outside the jail, police stations, and courts demanding his release, which was unwillingly granted. Gandhi then organized protests and strikes against the landlords, who finally agreed to more pay and allowed the farmers to determine what crops to raise. The government canceled tax collections until the famine ended.

In Kheda, Gandhi’s associate, Sardar Vallabhai Patel led the actions, guided by Gandhi's ideas. The revolt was astounding in terms of discipline and unity. Even when all their personal property, land, and livelihood were seized, a vast majority of Kheda's farmers remained firmly united in support of Patel. Gujaratis sympathetic to the revolt in other parts resisted the government machinery, and helped to shelter the relatives and property of the protesting peasants. Those Indians who sought to buy the confiscated lands were ostracized from society. Although nationalists like Sardul Singh Caveeshar called for sympathetic revolts in other parts, Gandhi and Patel firmly rejected the idea.

The government finally sought to foster an honorable agreement for both parties. The tax for the year in question and the next would be suspended, and the increase in rate reduced, while all confiscated property would be returned. The success in these situations spread throughout the country.

Gandhi used Satyagraha on a national level in 1919, the year the Rowlatt Act was passed, allowing the government to imprison persons accused of sedition without trial. Also that year, in Punjab, 1-2,000 people were wounded and 400 or more were killed by British troops in the Amritsar massacre.[1] A traumatized and angry nation engaged in retaliatory acts of violence against the British. Gandhi criticized both the British and the Indians. Arguing that all violence was evil and could not be justified, he convinced the national party to pass a resolution offering condolences to British victims and condemning the Indian riots.[2] At the same time, these incidents led Gandhi to focus on complete self-government and complete control of all government institutions. This matured into Swaraj, or complete individual, spiritual, political independence.

The first move in the Swaraj non-violent campaign was the famous Salt March. The government monopolized the salt trade, making it illegal for anyone else to produce it, even though it was readily available to those near the sea coast. Because the tax on salt affected everyone, it was a good focal point for protest. Gandhi marched 400 kilometers (248 miles) from Ahmedabad to Dandi, Gujarat, to make his own salt near the sea. In the 23 days (March 12 to April 6) it took, the march gathered thousands. Once in Dandi, Gandhi encouraged everyone to make and trade salt. In the next days and weeks, thousands made or bought illegal salt, and by the end of the month, more than 60,000 had been arrested. It was one of his most successful campaigns. Although Gandhi himself strictly adhered to non-violence throughout his life, even fasting until violence ceased, his dream of a unified, independent India was not achieved and his own life was taken by an assassin. Nevertheless, his ideals have lived on, inspiring those in many other countries to use non-violent civil disobedience against oppressive and unjust governments.

Poland

Civil disobedience was a tactic used by the Polish in protest of the former communist government. In the 1970s and 1980s, there occurred a deepening crisis within Soviet-style societies brought about by declining morale, worsening economic conditions (a shortage economy), and the growing stresses of the Cold War.[3] After a brief period of economic boom, from 1975, the policies of the Polish government, led by Party First Secretary Edward Gierek, precipitated a slide into increasing depression, as foreign debt mounted.[4] In June 1976, the first workers' strikes took place, involving violent incidents at factories in Radom and Ursus.[5]

On October 16, 1978, the Bishop of Kraków, Karol Wojtyła, was elected Pope John Paul II. A year later, during his first pilgrimage to Poland, his masses were attended by millions of his countrymen. The Pope called for the respecting of national and religious traditions and advocated for freedom and human rights, while denouncing violence. To many Poles, he represented a spiritual and moral force that could be set against brute material forces; he was a bellwether of change, and became an important symbol—and supporter—of changes to come. He was later to define the concept of "solidarity" in his Encyclical Sollicitudo Rei Socialis (December 30, 1987).[6]

On July of 1980, the government of Edward Gierek, facing an economic crisis, decided to raise the prices while slowing the growth of the wages. A wave of strikes and factory occupations began at once.[3] At the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk, workers were outraged at the sacking of Anna Walentynowicz, a popular crane operator and well-known activist who became a spark that pushed them into action.[7] The workers were led by electrician Lech Wałęsa, a former shipyard worker who had been dismissed in 1976, and who arrived at the shipyard on August 14.[3] The strike committee demanded rehiring of Anna Walentynowicz and Lech Wałęsa, raising a monument to the casualties of 1970, respecting of worker's rights and additional social demands.

By August 21, most of Poland was affected by the strikes, from coastal shipyards to the mines of the Upper Silesian Industrial Area. Thanks to popular support within Poland, as well as to international support and media coverage, the Gdańsk workers held out until the government gave in to their demands. Though concerned with labor union matters, the Gdańsk agreement enabled citizens to introduce democratic changes within the communist political structure and was regarded as a first step toward dismantling the Party's monopoly of power.[8]

Buoyed by the success of the strike, on the September 17, the representatives of Polish workers, including Lech Wałęsa, formed a nationwide trade union, Solidarity (Niezależny Samorządny Związek Zawodowy "Solidarność"). On December 16, 1980, the Monument to fallen Shipyard Workers was unveiled. On January 15, 1981, a delegation from Solidarity, including Lech Wałęsa, met Pope John Paul II in Rome. Between September 5 and 10 and September 26 to October 7, the first national congress of Solidarity was held, and Lech Wałęsa was elected its president.

In the meantime Solidarity transformed from a trade union into a social movement. Over the next 500 days following the Gdańsk Agreement, 9 to 10 million workers, intellectuals, and students joined it or its sub-organizations. It was the first and only recorded time in the history that a quarter of a country's population have voluntarily joined a single organization. "History has taught us that there is no bread without freedom," the Solidarity program stated a year later. "What we had in mind were not only bread, butter, and sausage but also justice, democracy, truth, legality, human dignity, freedom of convictions, and the repair of the republic."

Using strikes and other protest actions, Solidarity sought to force a change in the governmental policies. At the same time it was careful to never use force or violence, to avoid giving the government any excuse to bring the security forces into play. Solidarity's influence led to the intensification and spread of anti-communist ideals and movements throughout the countries of the Eastern Bloc, weakening their communist governments. In 1983, Lech Wałęsa received the Nobel Prize for Peace, but the Polish government refused to issue him a passport and allow him to leave the country. Finally, Roundtable Talks between the weakened Polish government and Solidarity-led opposition led to semi-free elections in 1989. By the end of August, a Solidarity-led coalition government was formed, and in December, Lech Wałęsa was elected president.

South Africa

Both Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Steve Biko advocated civil disobedience in the fight against apartheid. The result can be seen in such notable events as the 1989 Purple Rain Protest, and the Cape Town Peace March, which defied apartheid laws.

Purple rain protest

On September 2, 1989, four days before South Africa's racially segregated parliament held its elections, a police water cannon with purple dye was turned on thousands of Mass Democratic Movement supporters who poured into the city in an attempt to march on South Africa's Parliament on Burg Street in Cape Town. Protesters were warned to disperse but instead knelt in the street and the water cannon was turned on them. Some remained kneeling while others fled. Some had their feet knocked out from under them by the force of the jet. A group of about 50 protesters streaming with purple dye, ran from Burg Street, down to the parade. They were followed by another group of clergymen and others who were stopped in Plein Street. Some were then arrested. A lone protester, Philip Ivey, redirected the water cannon toward the local headquarters of the ruling National Party. The headquarters, along with the historic, white-painted Old Town House, overlooking Greenmarket Square, were doused with purple dye.[9]

On the Parade, a large contingent of police arrested everyone they could find who had purple dye on them. When they were booed by the crowd, police dispersed them. About 250 people marching under a banner stating, "The People Shall Govern," dispersed at the intersection of Darling Street and Sir Lowry Road after being stopped by police.[10]

Cape Town peace march

On September 12, 1989, 30,000 Capetonians marched in support of peace and the end of apartheid. The event lead by Mayor Gordon Oliver, Archbishop Tutu, Rev Frank Chikane, Moulana Faried Esack, and other religious leaders was held in defiance of the government's ban on political marches. The demonstration forced President de Klerk to relinquish the hardline against transformation, and the eventual unbanning of the ANC, and other political parties, and the release of Nelson Mandela less than six months later.

The United States

There is a long history of civil disobedience in the United States. One of the first practitioners was Henry David Thoreau whose 1849 essay, Civil Disobedience, is considered a defining exposition of the modern form of this type of action. It advocates the idea that people should not support any government attempting unjust actions. Thoreau was motivated by his opposition to the institution of slavery and the fighting of the Mexican-American War. Those participating in the movement for women's suffrage also engaged in civil disobedience.[11] The labor movement in the early twentieth century used sit-in strikes at plants and other forms of civil disobedience. Civil disobedience has also been used by those wishing to protest the Vietnam War, apartheid in South Africa, and against American intervention in Central America.[12]

Martin Luther King, Jr. is one of the most famous activists who used civil disobedience to achieve reform. In 1953, at the age of twenty-four, King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, in Montgomery, Alabama. King correctly recognized that organized, nonviolent protest against the racist system of southern segregation known as Jim Crow laws would lead to extensive media coverage of the struggle for black equality and voting rights. Indeed, journalistic accounts and televised footage of the daily deprivation and indignities suffered by southern blacks, and of segregationist violence and harassment of civil rights workers and marchers, produced a wave of sympathetic public opinion that made the Civil Rights Movement the single most important issue in American politics in the early-1960s. King organized and led marches for blacks' right to vote, desegregation, labor rights, and other basic civil rights. Most of these rights were successfully enacted into United States law with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to comply with the Jim Crow law that required her to give up her seat to a white man. The Montgomery Bus Boycott, led by King, soon followed. The boycott lasted for 382 days, the situation becoming so tense that King's house was bombed. King was arrested during this campaign, which ended with a United States Supreme Court decision outlawing racial segregation on all public transport.

King was instrumental in the founding of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957, a group created to harness the moral authority and organizing power of black churches to conduct nonviolent protests in the service of civil rights reform. King continued to dominate the organization. King was an adherent of the philosophies of nonviolent civil disobedience used successfully in India by Mahatma Gandhi, and he applied this philosophy to the protests organized by the SCLC.

Civil disobedience has continued to be used into the twenty-first century in the United States by protesters against numerous alleged injustices, including discrimination against homosexuals by church and other authorities, American intervention in Iraq, as well as by anti-abortion protesters and others.

Notes

- ↑ Gandhi's Life in 5000 words From the book Mahatma Gandhi - His Life in pictures. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ↑ Rajmohan Gandhi, Patel: A Life (Navjivan Trust, 2011, ISBN 978-8172291389).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Colin Barker, The rise of Solidarnosc International Socialism, October 17, 2005. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ↑ Keith John Lepak, Prelude to Solidarity (Columbia University Press, 1989, ISBN 0231066082).

- ↑ Barbara J. Falk, The Dilemmas of Dissidence in East-Central Europe: Citizen Intellectuals and Philosopher Kings (Central European University Press, 2003, ISBN 9639241393).

- ↑ George Weigel, The Final Revolution: The Resistance Church and the Collapse of Communism (Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 0195166647).

- ↑ The birth of Solidarity BBC News. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ↑ Norman Davies, God's Playground: A History of Poland, Vol. 1: The Origins to 1795 (Columbia University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0231128179).

- ↑ The Day the Purple Governed Sunday Times Heritage Project. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ↑ Scott Kract, 500 Arrested During Protest in Cape Town Los Angeles Times, September 3, 1989. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ↑ Woman Suffrage and the 19th Amendment The National Archives. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ↑ History of Mass Nonviolent Action Civil Disobedience Training. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Arendt, Hannah. Crises of the Republic: Lying in Politics; Civil Disobedience; On Violence; Thoughts on Politics and Revolution. Harvest Books, 1972. ISBN 0156232006

- Davies, Norman. God's Playground: A History of Poland, Vol. 1: The Origins to 1795. Columbia University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0231128179

- Falk, Barbara J. The Dilemmas of Dissidence in East-Central Europe: Citizen Intellectuals and Philosopher Kings. Central European University Press, 2003. ISBN 9639241393

- Gandhi, Rajmohan. Patel: A Life. Navjivan Trust, 2011. ISBN 978-8172291389

- Hendrick, George. Why Not Every Man? African Americans and Civil Disobedience in the Quest for the Dream. Ivan R. Dee, Publisher, 2005. ISBN 1566636450

- Lepak, Keith John. Prelude to Solidarity. Columbia University Press, 1989. ISBN 0231066082

- Polner, Murray, and Jim O'Grady. Disarmed and Dangerous: The Radical Life and Times of Daniel and Philip Berrigan, Brothers in Religious Faith and Civil Disobedience. Westview Press, 2001. ISBN 0813334497

- Thoreau, Henry David. On the Duty of Civil Disobedience. Book Jungle, 2007. ISBN 978-1594625268

- Thoreau, Henry David. Civil Disobedience And Other Essays the Collected Essays of Henry David Thoreau. Digireads.com, 2005. ISBN 978-1420925227

- Tolstoy, Leo. Writings on Civil Disobedience and Nonviolence. New Society Pub., 1987. ISBN 0865711097

- Weigel, George. The Final Revolution: The Resistance Church and the Collapse of Communism. Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0195166647

- Zinn, Howard. The Zinn Reader: Writings on Disobedience and Democracy. Seven Stories Press, 1997. ISBN 1888363541

External links

All links retrieved December 10, 2023.

- “Resistance to Civil Government” (“Civil Disobedience”) by H.D. Thoreau

- Civil Disobedience Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Civil_disobedience history

- Champaran_and_Kheda_Satyagraha history

- History_of_Solidarity history

- Martin_Luther_King,_Jr. history

- Purple_Rain_Protest history

- Cape_Town_Peace_March history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.