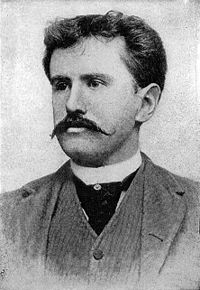

O. Henry

| William Sydney Porter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 11 1862 Greensboro, North Carolina, United States |

| Died | June 5 1910 (aged 47) New York City |

| Pen name | O. Henry, Olivier Henry |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | American |

O. Henry is the pen name of American writer William Sydney Porter (September 11, 1862 - June 5, 1910). O. Henry short stories are known for wit, wordplay, warm characterization, and clever twist endings.

Among his more famous offerings are "The Ransom of Red Chief," in which bumbling kidnappers abduct a lad so obnoxious that they are forced to pay the father to take him back, and "The Gift of the Magi," about a couple who so much want to give each other a Christmas gift that they each sell their most precious possession to buy the gift, and in so doing render each other's gift "useless." This story is recited countless times every Christmas to demonstrate the power of giving, echoing the words of Jesus that "it is more blessed to give than to receive."

Biography

Early life

Porter was born on September 11 1862, in Greensboro, North Carolina. His middle name at birth was Sidney; he changed the spelling in 1898. His parents were Dr. Algernon Sidney Porter (1825–1888) and Mary Jane Virginia Swain Porter (1833–1865). They were married April 20, 1858. When William was three, his mother died from tuberculosis, and he and his father moved into the home of his paternal grandmother. As a child, Porter was always reading. He read everything from classics to dime novels. His favorite reading was One Thousand and One Nights.

Porter graduated from his aunt Evelina Maria Porter's elementary school in 1876. He then enrolled at the Lindsey Street High School. His aunt continued to tutor him until he was 15. In 1879, he started working as a bookkeeper in his uncle's drugstore and in 1881, at the age of nineteen, he was licensed as a pharmacist. At the drugstore, he also showed off his natural artistic talents by sketching the townsfolk.

The move to Texas

Porter traveled with Dr. James K. Hall to Texas in March 1882, hoping that a change of air would help alleviate a persistent cough he had developed. He took up residence on the sheep ranch of Richard Hall, James' son, in La Salle County and helped out as a shepherd, ranch hand, cook, and baby-sitter. While on the ranch, he learned bits of Spanish and German from the mix of immigrant ranch hands. He also spent time reading classic literature.

Porter's health did improve and he traveled with Richard to Austin in 1884, where he decided to remain and was welcomed into the home of the Harrells, who were friends of Richard's. Porter took a number of different jobs over the next several years, first as pharmacist then as a draftsman, bank teller, and journalist. He also began writing as a sideline to employment.

He led an active social life in Austin, including membership in singing and drama groups. Porter was a good singer and musician. He played both the guitar and mandolin. He became a member of the "Hill City Quartet," a group of young men who sang at gatherings and serenaded young women of the town.

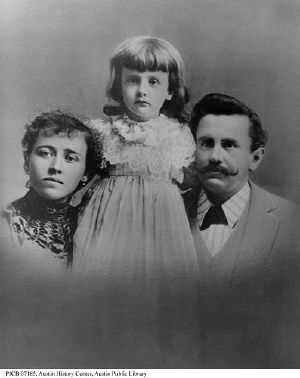

Porter met and began courting Athol Estes, then seventeen years old and from a wealthy family. Her mother objected to the match because Athol was ill, suffering from tuberculosis. On July 1, 1887, Porter eloped with Athol to the home of Reverend R. K. Smoot, where they were married.

The couple continued to participate in musical and theater groups, and Athol encouraged her husband to pursue his writing. Athol gave birth to a son in 1888, who died hours after birth, and then a daughter, Margaret Worth Porter, in September 1889.

Porter's friend, Richard Hall, became Texas Land Commissioner and offered Porter a job. Porter started as a draftsman at the Texas General Land Office (GLO) in 1887 at a salary of $100 a month, drawing maps from surveys and field notes. The salary was enough to support his family, but he continued his contributions to magazines and newspapers.

In the GLO building, he began developing characters and plots for such stories as "Georgia's Ruling" (1900), and "Buried Treasure" (1908). The castle-like building he worked in was even woven into some his tales such as "Bexar Scrip No. 2692" (1894). His job at the GLO was a political appointment by Hall. Hall ran for governor in the election of 1890, but lost. Porter resigned in early 1891, when the new governor was sworn in.

The same year, Porter began working at the First National Bank of Austin as a teller and bookkeeper at the same salary he had made at the GLO. The bank was operated informally and Porter had trouble keeping track of his books. In 1894, he was accused by the bank of embezzlement and lost his job but was not indicted.

He now worked full time on his humorous weekly called The Rolling Stone, which he started while working at the bank. The Rolling Stone featured satire on life, people and politics and included Porter's short stories and sketches. Although eventually reaching a top circulation of 1500, The Rolling Stone failed in April 1895, perhaps because of Porter's poking fun at powerful people. Porter also may have ceased publication as the paper never provided the money he needed to support his family. By then, his writing and drawings caught the attention of the editor at the Houston Post.

Porter and his family moved to Houston in 1895, where he started writing for the Post. His salary was only $25 a month, but it rose steadily as his popularity increased. Porter gathered ideas for his column by hanging out in hotel lobbies and observing and talking to people there. This was a technique he used throughout his writing career.

While he was in Houston, the First National Bank of Austin was audited and the federal auditors found several discrepancies. They managed to get a federal indictment against Porter. Porter was subsequently arrested on charges of embezzlement, charges which he denied, in connection with his employment at the bank.

Flight and return

Porter's father-in-law posted bail to keep Porter out of jail, but the day before Porter was due to stand trial on July 7, 1896, he fled, first to New Orleans and later to Honduras. While he was in Honduras, Porter coined the term "banana republic," subsequently used to describe almost any small tropical dictatorship in Latin America.

Porter had sent Athol and Margaret back to Austin to live with Athol's parents. Unfortunately, Athol became too ill to meet Porter in Honduras as Porter planned. When he learned that his wife was dying, Porter returned to Austin in February 1897 and surrendered to the court, pending an appeal. Once again, Porter's father-in-law posted bail so Porter could stay with Athol and Margaret.

Athol Estes Porter died on July 25, 1897, from tuberculosis (then known as consumption). Porter, having little to say in his own defense, was found guilty of embezzlement in February 1898, sentenced to five years jail, and imprisoned on March 25, 1898, as federal prisoner 30664 at the Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus, Ohio. While in prison, Porter, as a licensed pharmacist, worked in the prison hospital as the night druggist. Porter was given his own room in the hospital wing, and there is no record that he actually spent time in the cell block of the prison.

He had fourteen stories published under various pseudonyms while he was in prison, but was becoming best known as "O. Henry," a pseudonym that first appeared over the story, "Whistling Dick's Christmas Stocking," in the December 1899 issue of McClure's Magazine. A friend of his in New Orleans would forward his stories to publishers, so they had no idea the writer was imprisoned. Porter was released on July 24, 1901, for good behavior after serving three years.

Porter reunited with his daughter Margaret, then age 12, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where Athol's parents had moved after Porter's conviction. Margaret was never told that her father had been in prison, just that he had been away on business.

A brief stay at the top

Porter's most prolific writing period started in 1902, when he moved to New York City to be near his publishers. He wrote 381 short stories while living there. He wrote a story a week for over a year for the New York World Sunday Magazine. His wit, characterization and plot twists were adored by his readers, but often panned by the critics. Yet, he went on to gain international recognition and is credited with defining the short story as a literary art form.

Porter married again in 1907, to childhood sweetheart Sarah (Sallie) Lindsey Coleman, whom he met again after revisiting his native state of North Carolina. However, despite his publishing success (or perhaps because of the attendant pressure success brought), Porter drank heavily.

His health began to deteriorate in 1908, which affected his writing. Sarah left him in 1909, and Porter died on June 5, 1910, of cirrhosis of the liver, complications of diabetes, and an enlarged heart. After funeral services in New York City, he was buried in the Riverside Cemetery in Asheville, North Carolina. His daughter, Margaret Worth Porter, died in 1927, and was buried with her father.

Attempts were made to secure a presidential pardon for Porter during the administrations of Woodrow Wilson, Dwight Eisenhower, and Ronald Reagan. However, each attempt was met with the assertion that the Justice Department did not recommend pardons after death.

Literary output

O. Henry stories are famous for their surprise endings; such an ending is now often referred to as an "O. Henry ending." He was called the American answer to Guy de Maupassant. Both authors wrote twist endings, but O. Henry stories were much more playful and optimistic.

Most of O. Henry's stories are set in his own time, the early years of the twentieth century. Many take place in New York City, and deal for the most part with ordinary people: Clerks, policemen, waitresses, and so on. His stories are also well known for witty narration.

Fundamentally a product of his time, O. Henry's work provides one of the best English examples of catching the entire flavor of an age. Whether roaming the cattle-lands of Texas, exploring the art of the "gentle grafter," or investigating the tensions of class and wealth in turn of the century New York, O. Henry had an inimitable talent for isolating some element of society and describing it with an incredible economy and grace of language.

Collections

Some of his best and least-known work is contained in the collection Cabbages and Kings, a series of stories which each explore some individual aspect of life in a paralytically sleepy Central American town. Each story advances some aspect of the larger plot and relates back one to another in a complex structure which slowly explicates its own background even as it painstakingly erects a town which is one of the most detailed literary creations of the period.

The Four Million is another collection of stories. It opens with a reference to Ward McAllister's "assertion that there were only 'Four Hundred' people in New York City who were really worth noticing. But a wiser man has arisen—the census taker—and his larger estimate of human interest has been preferred in marking out the field of these little stories of the 'Four Million.'" To O. Henry, everyone in New York counted. He had an obvious affection for the city, which he called "Bagdad-on-the-Subway,"[1] and many of his stories are set there—but others are set in small towns and in other cities.

Stories

O. Henry's short stories are among the most famous short stories in American culture. They include:

- "A Municipal Report" which opens by quoting Frank Norris: "Fancy a novel about Chicago or Buffalo, let us say, or Nashville, Tennessee! There are just three big cities in the United States that are 'story cities'—New York, of course, New Orleans, and, best of the lot, San Francisco." Thumbing his nose at Norris, O. Henry sets the story in Nashville.

- One of O. Henry's most popular stories, "The Gift of the Magi" about a young couple who are short of money but desperately want to buy each other Christmas gifts. Unbeknownst to Jim, Della sells her most valuable possession, her beautiful hair, in order to buy a platinum fob chain for Jim's watch; while unbeknownst to Della, Jim sells his own most valuable possession, his watch, to buy jeweled combs for Della's hair. The essential premise of this story has been copied, re-worked, parodied, and otherwise re-told countless times in the century since it was written.

- "Compliments of the Season" is another of O. Henry's Christmas stories, describing several characters' misadventures during Christmas.[2]

- "The Ransom of Red Chief," in which two men kidnap a boy of ten. The boy turns out to be so bratty and obnoxious that the desperate men ultimately pay the boy's father $250 to take him back.

- "The Cop and the Anthem" about a New York City hobo named Soapy, who sets out to get arrested so he can avoid sleeping in the cold winter as a guest of the city jail. Despite efforts at petty theft, vandalism, disorderly conduct, and "mashing" with a young prostitute, Soapy fails to draw the attention of the police. Disconsolate, he pauses in front of a church, where an organ anthem inspires him to clean up his life–whereupon he is promptly charged for loitering and sentenced to three months in prison, exactly what he originally set to do.

- "A Retrieved Reformation," which tells the tale of safecracker Jimmy Valentine, recently freed from prison. He goes to a town bank to check it over before he robs it. As he walks to the door, he catches the eye of the banker's beautiful daughter. They immediately fall in love and Valentine decides to give up his criminal career. He moves into the town, taking up the identity of Ralph Spencer, a shoemaker. Just as he is about to leave to deliver his specialized tools to an old associate, a lawman who recognizes him arrives at the bank. Jimmy and his fiancé and her family are at the bank, inspecting a new safe, when a child accidentally gets locked inside the airtight vault. Knowing it will seal his fate, Valentine opens the safe to rescue the child. Showing compassion for his good deed, the lawman lets him go.

- "After Twenty Years," set on a dark street in New York, focuses on a man named "Silky" Bob who is fulfilling an appointment made 20 years ago to meet his friend Jimmy at a restaurant. A beat cop questions him about what he is doing there. Bob explains, and the policeman leaves. Later, a second policeman comes up and arrests Bob. He gives Bob a note, in which the first policeman explains that he was Jimmy, come to meet Bob, but he recognized Bob as a wanted man. Unwilling to arrest his old friend, he went off to get another officer to make the arrest.

Origin of his pen name

Porter gave various explanations for the origin of his pen name.[3] In 1909, he gave an interview to The New York Times, in which he gave an account of it:

It was during these New Orleans days that I adopted my pen name of O. Henry. I said to a friend: "I'm going to send out some stuff. I don't know if it amounts to much, so I want to get a literary alias. Help me pick out a good one." He suggested that we get a newspaper and pick a name from the first list of notables that we found in it. In the society columns we found the account of a fashionable ball. "Here we have our notables," said he. We looked down the list and my eye lighted on the name Henry, "That'll do for a last name," said I. "Now for a first name. I want something short. None of your three-syllable names for me." "Why don’t you use a plain initial letter, then?" asked my friend. "Good," said I, "O is about the easiest letter written, and O it is."

A newspaper once wrote and asked me what the O stands for. I replied, "O stands for Olivier the French for Oliver." And several of my stories accordingly appeared in that paper under the name Olivier Henry.[4]

Writer and scholar Guy Davenport offers another explanation: "[T]he pseudonym that he began to write under in prison is constructed from the first two letters of Ohio and the second and last two of penitentiary." (bold added)[3]

Both versions may well be apocryphal.

Legacy

The O. Henry Award is the only yearly award given to short stories of exceptional merit. The award is named after the American master of the form, O. Henry.

The O. Henry Prize Stories is an annual collection of the year's twenty best stories published in U.S. and Canadian magazines, written in English.

The award itself is called the O. Henry Award,[5] not the O. Henry Prize, though until recently there were first, second, and third prize winners; the collection is called The O. Henry Prize Stories, and the original collection was called Prize Stories 1919: The O. Henry Memorial Awards.

History and format

The award was first presented in 1919.[5] As of 2003, the series editor chooses twenty short stories, each one an O. Henry Prize Story. All stories originally written in the English language and published in an American or Canadian periodical are eligible for consideration. Three jurors are appointed annually. The jurors receive the twenty prize stories in manuscript form, with no identification of author or publication. Each juror, acting independently, chooses a short story of special interest and merit, and comments on that story.

The goal of The O. Henry Prize Stories remains to strengthen the art of the short story. Starting in 2003, The O. Henry Prize Stories is dedicated to a writer who has made a major contribution to the art of the short story. The O. Henry Prize Stories 2007 was dedicated to Sherwood Anderson, a U.S. short-story writer. Jurors for 2007 were Charles D'Ambrosio, Lily Tuck, and Ursula K. Le Guin.

Ironically, O. Henry is a household name in Russia, as his books enjoyed excellent translations and some of his stories were made into popular movies, the best known being, probably, The Ransom of Red Chief. The phrase "Bolivar cannot carry double" from "The Roads We Take" has become a Russian proverb, whose origin many Russians do not even recognize.

The house that the Porters rented in Austin from 1893 to 1895, moved from its original location in 1930 and restored, opened as the O. Henry Museum in 1934. The William Sidney Porter House is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

O. Henry in fiction

- William Sydney Porter is the chief protagonist of the novel A Twist at the End: A Novel of O. Henry (Simon & Schuster, 2000) by Steven Saylor.

Notes

- ↑ O. Henry, The Trimmed Lamp, Project Gutenberg text. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ↑ Literature Collection, Compliments of the Season by O. Henry. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Guy Davenport, The Hunter Gracchus and Other Papers on Literature and Art (Washington, D.C.: Counterpoint, 1996).

- ↑ New York Times, 'O. Henry' on Himself, Life, and Other Things. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Random House, O. Henry Award FAQ. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ainslee's Magazine. Magazine Data File. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- Austin Library. O. Henry Austin Chronology. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- bdb.co.za. Baghdad on the Subway. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- Current-Garcia, Eugene, O. Henry (William Sydney Porter), Twayne Publishers, 1965. OCLC 965352.

- Current-Garcia, Eugene, O. Henry: a Study of the Short Fiction, 1993. Maxwell Macmillian International. ISBN 9780805708592

- NexText. O. Henry.

- Online Literature. Biography And Stories. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- Pride and Prejudice86. About O. Henry Retrieved November 6, 2008.

External links

All links retrieved November 17, 2022.

- Works by O. Henry. Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.