| Oat | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Oat plants with inflorescences

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Avena sativa L. (1753) |

Oat, usually in the plural as oats, is any of the various plants of the genus Avena of the grass family (Poaceae), some of which are widely cultivated for their edible seeds (botanically a type of simple dry fruit called a caryopsis). In particular, oats refers to the common cereal plant Avena sativa, and to its edible grains, which are used for food, livestock feed, hay, pasture, and silage. Other well known plants of this genus are wild oat (A. fatua), red oat (A. byzantina), and wild red oat (A steriles). In all, there are about ten to fifteen Avena species and subspecies. This article will mainly be about A. sativa, which is one of the most important grain crops worldwide.

While oats are suitable for human consumption, used particularly as oatmeal and rolled oats, one of the most common uses is as livestock feed. In the United States, less than five percent of the total production is used for food, with most oats used for livestock feed (CNCPP 1999). Oats make up a large part of the diet of horses and are regularly fed to cattle as well. Oats are also used in some brands of dog and chicken feed.

Oats are the third most important grain crop in the United States (CNCPP 1999) and are seventh in weight of production worldwide, after maize, rice, wheat, barley, sorghum, and millet (FAO 2008). In 2007, almost 26 million metric tons of oats were produced worldwide (FAO 2008).

Overview and description

The true grasses known as oats, Avena sp., are native to Europe, Asia and northwest Africa. One species, Avena sativa is widely cultivated elsewhere, and several have become naturalized in many parts of the world. The wild ancestor of Avena sativa (common oat) and the closely-related minor crop, A. byzantina (red oat), is the hexaploid wild oat A. sterilis. Genetic evidence shows that the ancestral forms of A. sterilis grew in the Fertile Crescent of the Near East. Domesticated oats appear relatively late, and far from the Near East, in Bronze Age Europe. This is substantially later than wheat, and the early uses of oats appears to have been medicinal (CNCPP 1999). Oats, like rye, are usually considered a secondary crop; in other words, derived from a weed of the primary cereal domesticates wheat and barley. As these cereals spread westwards into cooler, wetter areas, this may have favored the oat weed component, leading to its eventual domestication (Zhou et al. 1999).

All oats have edible seeds, though they are small and hard to harvest in most species.

Oat plants are annual grasses. The main stem may grow to two or more feet, terminating in a large, generally loose panicle. A panicle is a compound raceme, a loose, much-branched indeterminate inflorescence with pedicellate flowers (and fruit) attached along the secondary branches—in other words, a branched cluster of flowers in which the branches are racemes. In oats, the panicle consists of a central stem (or rachis), side or rachis branches (which rise in whorls at the nodes), and spikelets in which the flowers and seeds are borne (CNCPP 1999). Each main stem and lateral stem ends in a spikelet, and spikelets also are found at the nodes of the branch stems; there may be 20 to 150 spikelets on one panicle (CNCPP 1999).

Cultivated oats

One species, Avena sativa, is of major commercial importance as a cereal grain. Four other species are grown as crops of minor or regional importance.

- Avena sativa, common oat or tree oat. Avena sativa is a cereal crop of global importance and the species commonly referred to as "oats." All members of this species are characterized by a panicle with a roughly pyramidal shape with equilateral branches spreading outward (CNCPP 1999). It is distinguished from A. byzantina, the red oak, by its spikelets separating from the pedicel by fracture, leaving no basal scar, while in red oats and some other species the separation takes place by abscission, leaving a definite scar (CNCPP 1999). One subspecies, A. sativa subsp. orientalis, is known as the common side oats, and is of much less economic importance.

- Avena abyssinica, Ethiopian oat. Zohary and Hopf (2000) note that Avena abyssinica is a "half-weed, half-crop confined to the highlands of Ethiopia." Stems are erect, tend to be small, and are fairly stiff, and panicles are equilateral, medium in size, and very drooping (CNCPP 1999).

- Avena byzantina, red oat. Avena byzantina has stems that are usually slender, reddish in color, and rather stiff, and the panicles are narrow, small, and erect with relatively few spikelets (CNCPP 1999). The two flowers of the spikelet adhere tightly to one another and separate by fracture of the stem or rachilla at the base, and the lemmas (specialized bracts enclosing a floret in a grass inflorescence) adhere to the kernal and have weak, non-twisted awns (CNCPP 1999). There are a number of important cultivate varieties of both winter and spring varieties grown in the southern half of the United States (CNCPP 1999), and it is a minor crop in the Near and Middle East.

- Avena nuda, naked oat, hulless oat, or large naked oat. Avena nuda has the caryopsis or kernal that is loose within the palea, as with the wheat (CNCPP 1999). This species plays much the same role in Europe as does A. abyssinica in Ethiopia. It is sometimes included in A. sativa and was widely grown in Europe before the latter replaced it. As its nutrient content is somewhat better than that of common oat, A. nuda has increased in significance in recent years, especially in organic farming

- Avena strigosa, lopsided oat, bristle oat, or sand oat. In Avena strigosa, the lemmas are lance-like, extending to two distinct points, and the plant has small, erect stems, and near equilateral panicles (CNCPP 1999). It is grown for fodder in parts of Western Europe and Brazil.

Wild oats

These species, called wild oats or oat-grasses, are nuisance weeds in cereal crops, as, being grasses like the crop, they cannot be chemically removed; any herbicide that would kill them would also damage the crop.

- Avena barbata, slender wild oat, or slender oat. Avena barbata has stems that are weak and small, yielding a decumbent growth habit, and panicles are equilateral, drooping, and rather large (CNCPP 1999).

- Avena fatua, wild oat or common wild oat. Avena fatua resembles A. sativa but is of greater vigor. It has very large and drooping panicles and the spikelets have long twisting awns and separate by abscission from their pedicles. Although it is of some value as hay or for pasturage, it is not grown for grain and is a troublesome weed (CNCPP 1999).

- Avena sterilis, winter wild oat or wild red oat. Avena sterilis is believed to be the ancestor of the cultivated red oats. It has large, harily lemmas, with strong twisted awns, adhering tightly to the kernal (CNCPP 1999).

- Avena brevis, short oat.

- Avena maroccana, Moroccan oat.

- Avena occidentalis, western oat.

- Avena pubescens, downy oat-grass.

- Avena pratensis, meadow oat-grass.

- Avena spicata, poverty oat-grass.

Production and processing of Avena sativa

| Top Oats Producers in 2005 | |

| (million metric tons) | |

| 5.1 | |

| 3.3 | |

| 1.7 | |

| 1.3 | |

| 1.2 | |

| 1.1 | |

| 1.0 | |

| 0.8 | |

| 0.8 | |

| 0.8 | |

| World Total | 24.6 |

| Source: UN Food & Agriculture Organisation (FAO)[1] | |

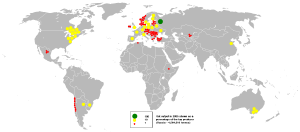

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations reports that the production of oat in 2007 was 25,991, 961 metric tons, which is up from 22,758,002 metric tons in 2006, but down considerably from the 1961 production of 49,588,769 metric tons. The area harvested in 2007 was 11,951,617 hectares (FAO 2008).

Oats are grown throughout the temperate zones. They have a lower summer heat requirement and greater tolerance of rain than other cereals like wheat, rye, or barley, so are particularly important in areas with cool, wet summers, such as Northwest Europe, even being grown successfully in Iceland.

Cultivation

Oats are an annual plant and can be planted either in autumn (for harvesting the next year) or in the spring (for early autumn harvest). For spring planting, an early start is important for good yields as oats will go dormant during the summer heat. Oats are cold-tolerant and will be unaffected by late frosts or snow.

Typically, in industrialized environments, about 125 to 175 kilograms/hectare (between 2.75 and 3.25 bushels per acre) are sown, either broadcast, drilled, or planted using an airseeder. Lower rates are used when underseeding with a legume. Somewhat higher rates can be used on the best soils, or where there are problems with weeds. Excessive sowing rates will lead to problems with lodging and may reduce yields.

Winter oats may be grown as an off-season groundcover and plowed under in the spring as a green fertilizer.

Oats remove substantial amounts of nitrogen from the soil. Usually 50 to 100 kilograms per hectare (45–90 pounds per acre) of nitrogen in the form of urea or anhydrous ammonia is sufficient to add to the soil, as oats uses about 1 pound per bushel per acre. A sufficient amount of nitrogen is particularly important for plant height and hence straw quality and yield. When the prior-year crop was a legume, or where ample manure is applied, nitrogen rates can be reduced somewhat.

Oats also remove phosphorus in the form of P2O5 at the rate of 0.25 pound per bushel per acre. Phosphate is thus added to the soil. Oats remove potash (K2O) at a rate of 0.19 pound per bushel per acre, which causes it to use 15 to 30 kilograms per hectare, or 13 to 27 pounds per acre.

The vigorous growth habit of oats will tend to choke out most weeds. A few tall broadleaf weeds, such as ragweed, goosegrass, wild mustard, and buttonweed (velvetleaf), can occasionally be a problem as they complicate harvest and reduce yields. These may be controlled with a modest application of a broadleaf herbicide such as 2,4-D while the weeds are still small.

Oats are relatively free from diseases and pests, with the exception being leaf diseases, such as leaf rust and stem rust. A few Lepidoptera caterpillars feed on the plants—e.g., rustic shoulder-knot (Apamea sordens) and setaceous Hebrew character (Xestia c-nigrum)—but these rarely become a major pest.

Harvesting and storage

Modern harvest technique is a matter of available equipment, local tradition, and priorities. Best yields are attained by swathing, cutting the plants at about 10 centimeters (4 inches) above ground, and putting them into windrows with the grain all oriented the same way, when the kernels have reached 35 percent moisture, or when the greenest kernels are just turning cream-color. The windrows are left to dry in the sun for several days before being combined using a pickup header. Then the straw is baled.

Oats can also be left standing until completely ripe and then combined with a grain head. This will lead to greater field losses, as the grain falls from the heads, and to greater harvesting losses, as the grain is threshed out by the reel. Without a draper head, there will also be somewhat more damage to the straw since it will not be properly oriented as it enters the throat of the combine. Overall yield loss is 10–15 percent compared to proper swathing.

Historical harvest methods involved cutting with a scythe or sickle, and threshing under the feet of cattle. Late nineteenth century and early twentieth century harvesting was performed using a binder. Oats were gathered into shocks and then collected and run through a stationary threshing machine.

After it is combined, the oats typically are transported to the farmyard using a grain truck, semi, or road train, where it is augered or conveyed into a bin for storage. Sometimes, when there is not enough bin-space, it is augered into portable grain rings, or piled on the ground. Oats can be safely stored at 12 percent moisture; at higher moisture levels, it must be aereated, or dried.

Yield and quality

In the United States, Oats listed as No. 1 oats weighs 42 pounds per bushel, while No. 3 oats must weigh at least 38 pounds per bushel. If it weighs over 36 pounds per bushel, it is a No. 4, and anything under 36 pounds per bushel is graded as "light weight." Note, however, that oats are bought and sold, and yields are figured, on the basis of a bushel equal to 32 pounds in the United States. A Canadian bushel of oats, however, is 34 pounds.

Yields range from 60 to 80 bushels on marginal land, to 100 to 150 bushels per acre on high-producing land. The average production is 100 bushels per acre, or 3.5 metric tons per hectare.

Straw yields are variable, ranging from one to three metric tons per hectare, mainly due to available nutrients, and the variety used (some are short-strawed, meant specifically for straight-combining).

Processing

Oats processing is a relatively simple process, which follows the following typical procedure.

- Cleaning and sizing. Upon delivery to the milling plant, chaff, rocks, other grains, and other foreign material are removed from the oats.

- Dehulling. Separation of the outer hull from the inner oat groat is effected by means of centrifugal acceleration. Oats are fed by gravity onto the center of a horizontally spinning stone, which accelerates them towards an outer ring. Groat and hull are separated on impact with this ring. The lighter oat hulls are then aspirated away while the denser oat groats are taken to the next step of processing. Oat hulls can be used as feed, processed further into insoluble oat fiber, or used as a biomass fuel.

- Kilning. The unsized oat groats will then pass through a heat and moisture treatment to balance moisture, but mainly to stabilize the groat. Oat groats are high in fat (lipids) and once exposed from their protective hull, enzymatic (lipase) activity begins to break down the fat into free fatty acids, ultimately causing an off flavor or rancidity. Oats will begin to show signs of enzymatic rancidity within four days of being dehulled and not stabilized. The kilning process is primarily done in food grade plants, not in feed grade plants. An oat groat is not considered a raw oat groat if it has gone through this process: the heat has disrupted the germ, and the oat groat will not sprout.

- Sizing of groats. Many whole oat groats are broken during the dehulling process, leaving the following types of groats to be sized and separated for further processing: Whole Oat Groats, Coarse Steel Cut Groats, Steel Cut Groats, and Fine Steel Cut Groats. Groats are sized and separated using screens, shakers, and indent screens. After the whole oat groats are separated, the remaining broken groats get sized again into the three groups (Coarse, Regular, Fine) and then stored. The term steel cut is referred to all sized or cut groats. When there are not enough broken to size for further processing, then whole oat groats get sent to a cutting unit with steel blades that will evenly cut the groats into the three sizes as discussed earlier.

- Final processing. Three methods are used to make the finished product:

- Flaking. This process uses two large smooth or corrugated rolls spinning at the same speed in opposite directions at a controlled distance. Oat flakes, also known as Rolled Oats, have many different sizes, thicknesses, and other characteristics depending on the size of oat groat passed between the rolls. Typically, the three sizes of steel cut oats are used to make Instant, Baby, and Quick rolled oats, whereas whole oat groats are used to make Regular, Medium, and Thick Rolled Oats. Oat flakes range from a thickness of 0.014" to 0.040".

- Oat bran milling. This process takes the oat groats through several roll stands that flatten and separate the bran from the flour (endosperm). The two separate products (flour and bran) get sifted through a gyrating sifter screen to further separate them. The final products are oat bran and debranned oat flour.

- Whole flour milling. This process takes oat groats straight to a grinding unit (stone or hammer mill) and then over sifter screens to separate the coarse flour and final whole oat flour. The coarser flour gets sent back to the grinding unit until it's ground fine enough to be whole oat flour. This method is used very much in India.

Uses

Uses as food

Historical attitudes towards oats as food for humans vary. Oat bread was first manufactured in England, where the first oat bread factory was established in 1899. In Scotland they were, and still are, held in high esteem, as a mainstay of the national diet. However, a traditional saying in England is that "oats are only fit to be fed to horses and Scotsmen," to which the Scottish riposte is "and England has the finest horses, and Scotland the finest men." Samuel Johnson notoriously defined oats in his Dictionary as "a grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people." Given the centrality of oats in traditional Scottish cuisine, it is not surprising that in Scottish English, the word "corn," when otherwise unqualified, refers to oats, just as in England it refers to wheat and in North America and Australia, to maize (Partridge and Whitcut 1995).

Oats have numerous uses in food. Most commonly, they are rolled or crushed into oatmeal, or ground into fine oat flour. Oatmeal is chiefly eaten as porridge, but may also be used in a variety of baked goods, such as oatcakes, oatmeal cookies, and oat bread. Oats are also an ingredient in many cold cereals, in particular muesli and granola. Oats may also be consumed raw, and cookies with raw oats are becoming popular.

Oats are also occasionally used in Britain for brewing beer. Oatmeal stout is one variety brewed using a percentage of oats for the wort. The more rarely used Oat Malt is produced by the Thomas Fawcett & Sons Maltings and was used in the Maclay Oat Malt Stout before Maclay ceased independent brewing operations.

In Scotland, a dish called Sowans was made by soaking the husks from oats for a week so that the fine, floury part of the meal remained as sediment to be strained off, boiled, and eaten (Gauldie 1981).

Other uses

Oats are also commonly used as feed for horses, where it is dehulled and rolled. Cattle are also fed oats, either whole, or ground into a coarse flour using a roller mill, burr mill, or hammer mill.

Oat straw is prized by cattle and horse producers as bedding, due to its soft, relatively dust-free, and absorbent nature. The straw can also be used for making corn dollies.

Oat extract can also be used to soothe skin conditions, such as skin lotions. It is the principal ingredient for the Aveeno line of products.

Health

| Oats Nutritional value per 100 g | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy 390 kcal 1630 kJ | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Percentages are relative to US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient database | |||||||||||||||||

Oats are generally considered "healthy," or a health food, being touted commercially as nutritious. The discovery of the healthy cholesterol-lowering properties has led to wider appreciation of oats as human food.

Soluble fiber

Oat bran is the outer casing of the oat. Its consumption is believed to lower LDL ("bad") cholesterol, and possibly to reduce the risk of heart disease.

After reports found that oats can help lower cholesterol, an "oat bran craze" swept the United States in the late 1980s, peaking in 1989, when potato chips with added oat bran were marketed. The food fad was short-lived and faded by the early 1990s. The popularity of oatmeal and other oat products again increased after a January 1998 decision by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) when it issued its final rule allowing a health claim to be made on the labels of foods containing soluble fiber from whole oats (oat bran, oat flourm and rolled oats), noting that 3.00 grams of soluble fiber daily from these foods, in conjunction with a diet low in saturated fat, cholesterol, and fat may reduce the risk of heart disease. In order to qualify for the health claim, the whole oat-containing food must provide at least 0.75 grams of soluble fiber per serving. The soluble fiber in whole oats comprises a class of polysaccharides known as Beta-D-glucan.

Beta-D-glucans, usually referred to as beta-glucans, comprise a class of non-digestible polysaccharides widely found in nature in sources such as grains, barley, yeast, bacteria, algae, and mushrooms. In oats, barley, and other cereal grains, they are located primarily in the endosperm cell wall.

Oat beta-glucan is a soluble fiber. It is a viscous polysaccharide made up of units of the sugar D-glucose. Oat beta-glucan is comprised of mixed-linkage polysaccharides. This means that the bonds between the D-glucose or D-glucopyranosyl units are either beta-1, 3 linkages or beta-1, 4 linkages. This type of beta-glucan is also referred to as a mixed-linkage (1→3), (1→4)-beta-D-glucan. The (1→3)-linkages break up the uniform structure of the beta-D-glucan molecule and make it soluble and flexible. In comparison, the non-digestible polysaccharide cellulose is also a beta-glucan but is non-soluble. The reason that it is non-soluble is that cellulose consists only of (1→4)-beta-D-linkages. The percentages of beta-glucan in the various whole oat products are: oat bran, greater than 5.5 percent and up to 23.0 percent; rolled oats, about 4 percent; whole oat flour about 4 percent.

Oats, after corn (maize), have the highest lipid content of any cereal, being greater than 10 percent for oats and as high as 17 percent for some maize cultivars, compared to about 2–3 percent for wheat and most other cereals. The polar lipid content of oats (about 8–17 percent glycolipid and 10–20 percent phospholipid or a total of about 33 percent) is greater than that of other cereals since much of the lipid fraction is contained within the endosperm.

Protein

Oat is the only cereal containing a globulin or legume-like protein, avenalin, as the major (80 percent) storage protein. Globulins are characterized by water solubility; because of this property, oats may be turned into a milky liquid but not into bread. The more typical cereal proteins such as gluten and zein are prolamines (prolamins). The minor protein of oat is a prolamine: avenin.

Oat protein is nearly equivalent in quality to soy protein, which has been shown by the World Health Organization to be equal to meat, milk, and egg protein. The protein content of the hull-less oat kernel (groat) ranges from 12–24 percent, the highest among cereals (Lasztity 1999).

Celiac disease

Coeliac disease, or celiac disease, is a disease often associated with ingestion of wheat, or more specifically a group of proteins labeled prolamines, or more commonly, gluten. The name of the disease comes from the Greek koiliakos, meaning "suffering in the bowels."

The role of oats in a gluten free diet remains controversial. Oats lack many of the prolamines found in wheat; however, oats do contain avenin (Rottmann 1996). Avenin is a prolamine that is toxic to the intestinal submucosa and can trigger a reaction in some celiacs (CSA 2008). A number of studies suggest that the presence of oats in gluten-free diet may be potentially harmful to individuals with coeliac disease (Silano et al. 2007; Arentz-Hansen et al. 2004).

However, there also are several studies suggesting that oats can be a part of a gluten free diet if it is pure (Hogberg et al. 2004). The first such study was published in 1995 (Janatuinen et al. 1995). A follow-up study indicated that it is safe to use oats even for a longer period (Janatuinen et al. 2002).

Notably, oats are frequently processed near wheat, barley and other grains, such that they become contaminated with other glutens. Because of this, the FAO's Codex Alimentarius Commission officially lists them as a crop containing gluten. Oats from areas where less wheat is grown, such as Ireland and Scotland, are less likely to be contaminated in this way. Oats are part of a gluten free diet in, for example, Finland and Sweden. In both of these countries there are "pure oat" products on the market.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Arentz-Hansen, H., B. Fleckenstein, O. Molberg, H. Scott, F. Koning, G. Jung, P. Roepstorff, K. E. Lundin, and L. M. Sollid. 2004. The molecular basis for oat intolerance in patients with celiac disease. PLoS Med. 1(1):e1. PMID 15526039. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- Celiac Sprue Association (CSA). 2008. The scoop on oats. Celiac Sprue Association/United States of America. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- Center for New Crops and Plant Products (CNCPP). 1999. Oats (Gramineae. Avena sp.. New Crops Resource Online Program (NewCROP). Retrieved August 26, 2008.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2008. ProdSTAT. FAOSTAT. Retrieved August 26, 2008.

- Gauldie, E. 1981. The Scottish Miller 1700 - 1900. John Donald. ISBN 0859760677.

- Hogberg,L., P. Laurin, K. Falth-Magnusson, C. Grant, E. Grodzinsky, G. Jansson, H. Ascher, L. Browaldh, J. A. Hammersjo, E. Lindberg, U. Myrdal, and L. Stenhammar. 2004. Oats to children with newly diagnosed coeliac disease: A randomized double blind study. Gut 53(5): 649-54. PMID 15082581. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- Janatuinen, E. K., P. H. Pikkarainen, T. A. Kemppainen, et al. 1995. [url=http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/333/16/1033 A comparison of diets with and without oats in adults with celiac disease]. New England Journal of Medicine 333(16): 1033-1037. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- Janatuinen, E. K., T. A. Kemppainen, R. J. K. Julkunen, V.-M. Kosma, M. Mäki, M. Heikkinen, and M. I. Uusitupa. 2002. No harm from five year ingestion of oats in celiac disease. Gut 50: 332-335. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- Lasztity, R. 1999. The Chemistry of Cereal Proteins. Akademiai Kiado. ISBN 9780849327636.

- Partridge, E., and J. Whitcut. Eds. 1995. Usage and Abusage: A Guide to Good English. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0393037614. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- Rottmann, L. H. 1996. On the use of oats in the gluten-free diet. Celiac Sprue Association/United States of America. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- Silano, M., M. Dessi, M. De Vincenzi, and H. Cornell. 2007. In vitro tests indicate that certain varieties of oats may be harmful to patients with coeliac disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 22(4): 528-31. PMID 17376046. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- Zhou, X., E. N. Jellen, and J. P. Murphy. 1999. Progenitor germplasm of domesticated hexaploid oat. Crop science 39: 1208-1214.

- Zohary, D. and M. Hopf. 2000. Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Cultivated Plants in West Asia, Europe, and the Nile Valley. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198503571.

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.