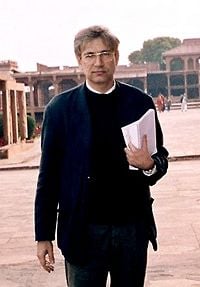

Orhan Pamuk

| Ferit Orhan Pamuk | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 7 1952 (age 71) Istanbul, Turkey |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Nationality | Turkish |

| Writing period | 1974–present |

| Literary movement | Postmodern literature |

| Notable work(s) | Karanlık ve Işık (Dark and Light; debut)

The White Castle |

| Notable award(s) | Nobel Prize in Literature 2006 |

| Influences | Thomas Mann, Jorge Luis Borges, Marcel Proust, William Faulkner, Albert Camus, Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Oğuz Atay, Walter Benjamin, Italo Calvino |

| Official website | |

Ferit Orhan Pamuk (born on June 7, 1952 in Istanbul) generally known simply as Orhan Pamuk, is a Nobel Prize-winning Turkish novelist and professor of comparative literature at Columbia University.[1] Pamuk is one of Turkey's most prominent novelists,[2] and his work has been translated into more than fifty languages. He is the recipient of numerous national and international literary awards. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature on October 12, 2006,[3] becoming the first Turkish person to receive a Nobel Prize.

Pamuk has been persecuted and prosecuted for his criticism of some episodes in the Turkish past, including genocide against the Kurds and Armenians. At the same time he has been critical of Western arrogance over their achievements, such as the Enlightenment and Modernism. Pamuk has sought to bridge the cultural difference between traditional society and modernity.

Biography

Pamuk was born in Istanbul in 1952 and grew up in a wealthy yet declining bourgeois family, an experience he describes in passing in his novels The Black Book and Cevdet Bey and His Sons, as well as more thoroughly in his personal memoir Istanbul. He was educated at Robert College prep school in Istanbul and went on to study architecture at the Istanbul Technical University. He left the architecture school after three years, however, to become a full-time writer, graduating from the Institute of Journalism at the University of Istanbul in 1976. From ages 22 to 30, Pamuk lived with his mother, writing his first novel and attempting to find a publisher.

On March 1, 1982, Pamuk married Aylin Turegen, a historian.[4] From 1985 to 1988, while his wife was a graduate student at Columbia University, Pamuk assumed the position of visiting scholar there, using the time to conduct research and write his novel The Black Book in the university's Butler Library. This period also included a visiting fellowship at the University of Iowa.

Pamuk returned to Istanbul. He and his wife had a daughter named Rüya born in 1991, whose name means "dream" in Turkish. In 2001, he and Aylin were divorced.

In 2006, after a period in which criminal charges had been pressed against him for his outspoken comments on the Armenian Genocide, Pamuk returned to the US to take up a position as a visiting professor at Columbia. Pamuk is currently a Fellow with Columbia's Committee on Global Thought and holds an appointment in Columbia's Middle East and Asian Languages and Cultures department and at its School of the Arts.

Pamuk was a writer in residence at Bard College (2004, 2007). In May 2007 Pamuk was among the jury members at the Cannes Film Festival headed by British director Stephen Frears. In the 2007-2008 academic year Pamuk returned to Columbia once again to jointly teach comparative literature classes with Andreas Huyssen and David Damrosch.

He completed his next novel, Masumiyet Müzesi (The Museum of Innocence) in the summer of 2007 in Portofino, Italy. It was released in January of 2008 in Turkey.[5] The German translation will appear shortly before the 2008 Frankfurt Book Fair where Pamuk was planning to hold an actual Museum of Innocence consisting of everyday odds and ends the writer has amassed (the exhibition will instead occur in an Istanbul house purchased by Pamuk).[6] Plans for an English translation have not been made public, but Erdağ Göknar received a 2004 NEA grant for the project.[7]

His older brother is Şevket Pamuk—who sometimes appears as a fictional character in Orhan Pamuk's work—an acclaimed professor of history, internationally recognized for his work in history of economics of the Ottoman Empire, while working at Bogazici University in Istanbul.

Work

| Turkish literature |

|---|

| By category |

| Epic tradition |

|

Orhon |

| Folk tradition |

|

Folk literature |

| Ottoman era |

|

Poetry · Prose |

| Republican era |

|

Poetry · Prose |

Orhan Pamuk started writing regularly in 1974.[8] His first novel, Karanlık ve Işık (Darkness and Light) was a co-winner of the 1979 Milliyet Press Novel Contest (Mehmet Eroğlu (* tr) was the other winner). This novel was published with the title Cevdet Bey ve Oğulları (Mr. Cevdet and His Sons) in 1982, and won the Orhan Kemal Novel Prize in 1983. It tells the story of three generations of a wealthy Istanbul family living in Nişantaşı, the district of Istanbul where Pamuk grew up.

Pamuk won a number of critical prizes for his early work, including the 1984 Madarali Novel Prize for his second novel Sessiz Ev (The Silent House) and the 1991 Prix de la Découverte Européenne for the French translation of this novel. His historical novel Beyaz Kale (The White Castle), published in Turkish in 1985, won the 1990 Independent Award for Foreign Fiction and extended his reputation abroad. The New York Times Book Review announced, "A new star has risen in the east–Orhan Pamuk." He started experimenting with postmodern techniques in his novels, a change from the strict naturalism of his early works.

Popular success took a bit longer to come to Pamuk, but his 1990 novel Kara Kitap (The Black Book) became one of the most controversial and popular readings in Turkish literature, due to its complexity and richness. In 1992, he wrote the screenplay for the movie Gizli Yüz (Secret Face), based on Kara Kitap and directed by a prominent Turkish director, Ömer Kavur. Pamuk's fourth novel Yeni Hayat (New Life) (1995), caused a sensation in Turkey upon its publication and became the fastest-selling book in Turkish history. By this time, Pamuk had also become a high-profile figure in Turkey, due to his support for Kurdish political rights. In 1995, Pamuk was among a group of authors tried for writing essays that criticized Turkey's treatment of the Kurds. In 1999, Pamuk published his story book Öteki Renkler (The Other Colors).

Pamuk's international reputation continued to increase when he published Benim Adım Kırmızı (My Name is Red) in 2000. The novel blends mystery, romance, and philosophical puzzles in a setting of 16th century Istanbul. It opens a window into the reign of Ottoman Sultan Murat III in nine snowy winter days of 1591, inviting the reader to experience the tension between East and West from a breathlessly urgent perspective. My Name Is Red has been translated into 24 languages and won the lucrative IMPAC Dublin Award in 2003.

Pamuk's most recent novel is Kar in 2002 (English translation, Snow, 2004), which explores the conflict between Islamism and Westernism in modern Turkey. The New York Times listed Snow as one of its Ten Best Books of 2004. He also published a memoir/travelogue İstanbul—Hatıralar ve Şehir in 2003 (English version, Istanbul—Memories and the City, 2005). Pamuk's Other Colors—a collection of non-fiction and a story—was published in the UK in September 2007. His next novel is titled The Museum of Innocence.

Asked how personal his book Istanbul: Memories and the City was, Pamuk replied “I thought I would write 'Memories and the City' in six months, but it took me one year to complete. And I was working twelve hours a day, just reading and working. My life, because of so many things, was in a crisis; I don’t want to go into those details: divorce, father dying, professional problems, problems with this, problems with that, everything was bad. I thought if I were to be weak I would have a depression. But every day I would wake up and have a cold shower and sit down and remember and write, always paying attention to the beauty of the book. Honestly, I may have hurt my mother, my family. My father was dead, but my mother is still alive. But I can’t care about that; I must care about the beauty of the book.”[9]

In 2005 Orhan Pamuk received the €25,000 Peace Prize of the German Book Trade for his literary work, in which "Europe and Islamic Turkey find a place for one another." The award presentation was held at Paul's Church, Frankfurt.

Motifs

Pamuk's books are characterized by a confusion or loss of identity brought on in part by the conflict between European and Islamic, or more generally Western and Eastern values. They are often disturbing or unsettling, but include complex, intriguing plots and characters of great depth. His works are also redolent with discussion of and fascination with the creative arts, such as literature and painting. Pamuk's work often touches on the deep-rooted tensions not only between East and West but between traditionalism and modernism/secularism.

Nobel Prize

On October 12, 2006, the Swedish Academy announced that Orhan Pamuk had been awarded the 2006 Nobel Prize in literature for Istanbul, confounding pundits and oddsmakers who had made Syrian poet Ali Ahmad Said, known as Adunis, a favorite.[10] In its citation, the Academy noted: "In the quest for the melancholic soul of his native city, [Pamuk] has discovered new symbols for the clash and interlacing of cultures."[3] Orhan Pamuk held his Nobel Lecture December 7, 2006, at the Swedish Academy, Stockholm. The lecture was entitled "Babamın Bavulu" (My Father's Suitcase)[11] and was given in Turkish. In the lecture he viewed the relations between Eastern and Western Civilizations in an allegorical upper text which covers his relationship with his father.

What literature needs most to tell and investigate today are humanity's basic fears: the fear of being left outside, and the fear of counting for nothing, and the feelings of worthlessness that come with such fears; the collective humiliations, vulnerabilities, slights, grievances, sensitivities, and imagined insults, and the nationalist boasts and inflations that are their next of kind …. Whenever I am confronted by such sentiments, and by the irrational, overstated language in which they are usually expressed, I know they touch on a darkness inside me. We have often witnessed peoples, societies and nations outside the Western world–and I can identify with them easily–succumbing to fears that sometimes lead them to commit stupidities, all because of their fears of humiliation and their sensitivities. I also know that in the West–a world with which I can identify with the same ease–nations and peoples taking an excessive pride in their wealth, and in their having brought us the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, and Modernism, have, from time to time, succumbed to a self-satisfaction that is almost as stupid.(Orhan Pamuk's Nobel Lecture, translation by Maureen Freely)

Criminal case

In 2005, after Pamuk made a statement regarding the mass killings of Armenians and Kurds in the Ottoman Empire, a criminal case was opened against the author based on a complaint filed by ultra-nationalist lawyer, Kemal Kerinçsiz.[12] The charges were dropped on 22 January, 2006. Pamuk has subsequently stated his intent was to draw attention to freedom of expression concerns.

Pamuk's statements

The criminal charges against Pamuk resulted from remarks he made during an interview in February 2005 with the Swiss publication Das Magazin, a weekly supplement to a number of Swiss daily newspapers: the Tages-Anzeiger, the Basler Zeitung, the Berner Zeitung and the Solothurner Tagblatt. In the interview, Pamuk stated, "Thirty thousand Kurds, and a million Armenians were killed in these lands and nobody dares to talk about it."

Pamuk has said that after the Swiss interview was published, he was subjected to a hate campaign that forced him to flee the country.[13] He returned later in 2005, however, to face the charges against him. In an interview with CNN TURK, he said that in his speech he used passive voice, and he did not give numbers like thirty thousand or one million. In an interview with BBC News, he said that he wanted to defend freedom of speech, which was Turkey's only hope for coming to terms with its history: "What happened to the Ottoman Armenians in 1915 was a major thing that was hidden from the Turkish nation; it was a taboo. But we have to be able to talk about the past."[14]

Prosecution

In June 2005, Turkey introduced a new penal code including Article 301, which states: "A person who, being a Turk, explicitly insults the Republic or Turkish Grand National Assembly, shall be punishable by imprisonment of between six months to three years." Pamuk was retroactively charged with violating this law in the interview he had given four months earlier. In October, after the prosecution had begun, Pamuk reiterated his views in a speech given during an award ceremony in Germany: "I repeat, I said loud and clear that one million Armenians and thirty thousand Kurds were killed in Turkey."[15]

Because Pamuk was charged under an ex post facto law, Turkish law required that his prosecution be approved by the Ministry of Justice. A few minutes after Pamuk's trial started on 16 December, the judge found that this approval had not yet been received and suspended the proceedings. In an interview published in the Akşam newspaper the same day, Justice Minister Cemil Çiçek said he had not yet received Pamuk's file but would study it thoroughly once it came.[16]

On December 29, 2005, Turkish state prosecutors dropped the charge that Pamuk insulted Turkey's armed forces, although the charge of "insulting Turkishness" remained.[17]

International reaction

The charges against Pamuk caused an international outcry and led to questions in some circles about Turkey's proposed entry into the European Union. On 30 November, the European Parliament announced that it would send a delegation of five MEPs, led by Camiel Eurlings, to observe the trial.[18] EU Enlargement Commissioner Olli Rehn subsequently stated that the Pamuk case would be a "litmus test" of Turkey's commitment to the EU's membership criteria.

On December 1, Amnesty International released a statement calling for Article 301 to be repealed and for Pamuk and six other people awaiting trial under the act to be freed.[19] PEN American Center also denounced the charges against Pamuk, stating: "PEN finds it extraordinary that a state that has ratified both the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the European Convention on Human Rights, both of which see freedom of expression as central, should have a Penal Code that includes a clause that is so clearly contrary to these very same principles."[20]

On December 13, eight world-renowned authors—José Saramago, Gabriel García Márquez, Günter Grass, Umberto Eco, Carlos Fuentes, Juan Goytisolo, John Updike and Mario Vargas Llosa—issued a joint statement supporting Pamuk and decrying the charges against him as a violation of human rights.[21]

Western reviewers

In a review of Snow in The Atlantic, Christopher Hitchens complained that "from reading Snow one might easily conclude that all the Armenians of Anatolia had decided for some reason to pick up and depart en masse, leaving their ancestral properties for tourists to gawk at."[22]

However, John Updike, reviewing the same book in The New Yorker, wrote: "To produce a major work so frankly troubled and provocatively bemused and, against the grain of the author’s usual antiquarian bent, entirely contemporary in its setting and subjects, took the courage that art sometimes visits upon even its most detached practitioners."[23]

Charges dropped

On January 22, 2006, the Justice Ministry refused to issue an approval of the prosecution, saying that they had no authority to open a case against Pamuk under the new penal code.[24] With the trial in the local court, it was ruled the next day that the case could not continue without Justice Ministry approval.[25] Pamuk's lawyer, Haluk İnanıcı, subsequently confirmed that charges had been dropped.

The announcement occurred in a week when the EU was scheduled to begin a review of the Turkish justice system.[26]

Aftermath

EU enlargement commissioner Olli Rehn welcomed the dropping of charges, saying 'This is obviously good news for Mr. Pamuk, but it's also good news for freedom of expression in Turkey.' However, some EU representatives expressed disappointment that the justice ministry had rejected the prosecution on a technicality rather than on principle. Reuters quoted an unnamed diplomat as saying, "It is good the case has apparently been dropped, but the justice ministry never took a clear position or gave any sign of trying to defend Pamuk."

Meanwhile, the lawyer who had led the effort to try Pamuk, Kemal Kerinçsiz, said he would appeal the decision, saying, "Orhan Pamuk must be punished for insulting Turkey and Turkishness, it is a grave crime and it should not be left unpunished."

Legacy

Pamuk and his book remain controversial. He has been lauded in the West, and vilified by some at home. On April 25, 2006, (in print in the May 8, 2006 issue) the magazine [[TIME (magazine)|TIME] listed Orhan Pamuk in the cover article "TIME 100: The People Who Shape Our World," in the category "Heroes & Pioneers," for speaking up.[27]

In April 2006, on the BBC's Hardtalk program, Pamuk stated that his remarks regarding the Armenian massacres were meant to draw attention to freedom of expression issues in Turkey rather than to the massacres themselves.[28]

On December 19-20, 2006 a symposium on Orhan Pamuk and His Work was held at Sabancı University, Istanbul. Pamuk himself gave the closing address.

In January 2008, 13 ultranationalists, including Kemal Kerinçsiz, were arrested by Turkish authorities for participating in a Turkish nationalist underground organization, named Ergenekon, allegedly conspiring to assassinate political figures, including several Christian missionaries and Armenian intellectual Hrant Dink.[29] Several reports suggest that Orhan Pamuk was among the figures this group plotted to kill.[30][31]

Awards

- 1979 Milliyet Press Novel Contest Award (Turkey) for his novel Karanlık ve Işık (co-winner)

- 1983 Orhan Kemal Novel Prize (Turkey) for his novel Cevdet Bey ve Oğulları

- 1984 Madarali Novel Prize (Turkey) for his novel Sessiz Ev

- 1990 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize (United Kingdom) for his novel Beyaz Kale

- 1991 Prix de la Découverte Européenne (France) for the French edition of Sessiz Ev : La Maison de Silence

- 1991 Antalya Golden Orange Film Festival (Turkey) Best Original Screenplay Gizli Yüz

- 1995 Prix France Culture (France) for his novel Kara Kitap : Le Livre Noir

- 2002 Prix du Meilleur Livre Etranger (France) for his novel My Name Is Red : Mon Nom est Rouge

- 2002 Premio Grinzane Cavour (Italy) for his novel My Name Is Red

- 2003 International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award (Ireland) for his novel My Name Is Red

- 2005 Peace Prize of the German Book Trade (Germany)

- 2005 Prix Medicis Etranger (France) for his novel Snow : La Neige

- 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature (Sweden)

- 2006 Washington University's Distinguished Humanist Award (United States)[32]

- 2007 Receives Georgetown University's Honorary Degree: Doctor of Humane Letters honoris causa [33]

Doctorates, honoris causa

- 2007 Free University of Berlin, Department of Philosophy and Humanities - May 4, 2007[34]

- 2007 Tilburg University - November 15, 2007[35]

- 2007 Boğaziçi University, Department of Western Languages and Literatures May 14, 2007

Bibliography in English

- The White Castle, translated by Victoria Holbrook, Manchester (UK): Carcanet Press Limited, 1991; New York: George Braziller, 1991 [original title: Beyaz Kale]

- The Black Book, translated by Güneli Gün, New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1994 [original title: Kara Kitap]. A new translation by Maureen Freely was published in 2006

- The New Life, translated by Güneli Gün, New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1997 [original title: Yeni Hayat]

- My Name is Red. translated by Erdağ M. Göknar, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001 [original title: Benim Adım Kırmızı]

- Snow, translated by Maureen Freely, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004 [original title: Kar]

- Istanbul: Memories of a City, translated by Maureen Freely, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005 [original title: İstanbul: Hatıralar ve Şehir]

- Other Colors: Essays and a Story, translated by Maureen Freely, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007 [original title: Öteki Renkler]

Bibliography in Turkish

- Cevdet Bey ve Oğulları (Cevdet Bey and His Sons), novel, Istanbul: Karacan Yayınları, 1982

- Sessiz Ev (The Silent House) , novel, Istanbul: Can Yayınları, 1983

- Beyaz Kale (The White Castle), novel, Istanbul: Can Yayınları, 1985

- Kara Kitap (The Black Book), novel, Istanbul: Can Yayınları, 1990

- Gizli Yüz (Secret Face), screenplay, Istanbul: Can Yayınları, 1992 [3]

- Yeni Hayat (The New Life), novel, Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 1995

- Benim Adım Kırmızı (My Name is Red), novel, Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 1998

- Öteki Renkler (Other Colors), essays, Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 1999

- Kar (Snow), novel, Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2002

- İstanbul: Hatıralar ve Şehir (Istanbul: Memories and the City), memoirs, Istanbul: Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2003

- Babamın Bavulu (My Father's Suitcase), three speeches, Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2007

Notes

All links Retrieved July 20, 2008.

- ↑ Turkey's Pamuk wins Nobel literature prize

- ↑ ARTS ABROAD; A Novelist Sees Dishonor in an Honor From the State, The New York Times

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 The Nobel Prize in Literature 2006. accessdate 2006-10-12

- ↑ "Pegasos," Finnish literary website

- ↑ "Today's Zaman," Turkish news website

- ↑ ORHAN PAMUK CANCELS “MUSEUM OF INNOCENCE”. "Art Forum"

- ↑ [1]theliterarysaloon.

- ↑ David Levinson, Karen Christensen. Encyclopedia of Modern Asia 458

- ↑ Joy E. Stocke, "The Melancholy Life of Orhan Pamuk", Wild River Review, November 19, 2007.

- ↑ Syrian Poet Favored To Win Prize, New York Times, October 12, 2006

- ↑ Nobel Lecture

- ↑ "Kerinçsiz puts patriotism before free speech, EU". Turkish Daily News, July 21, 2006.

- ↑ Author's trial set to test Turkey, BBC News.

- ↑ Author's trial set to test Turkey, BBC News.

- ↑ Writer repeats Turk deaths claim, BBC News.

- ↑ Turk writer's insult trial halted, BBC News.

- ↑ Partial reprieve for Turk writer, BBC News.

- ↑ Camiel Eurlings MEP leads delegation to observe trial of Orhan Pamuk, EEP-ED.

- ↑ Amnesty International, Article 301

- ↑ PEN Protests Charges Against Turkish Author Orhan Pamuk, PEN American Center.

- ↑ Literary world backs Pamuk, NTV

- ↑ Mind the Gap, Christopher Hitchens, The Atlantic Monthly

- ↑ John Updike, "Anatolian Arabesques: A modernist novel of contemporary Turkey," The New Yorker, August 30, 2004.

- ↑ Pamuk Case Dropped as Minister Says 'I have no Authorization for Permission' The ministry left the decision of whether to proceed , Zaman.

- ↑ Turkish court drops charges against novelist, The Independent

- ↑ Turkey drops charges against author, Scotsman.com News

- ↑ Orhan Pamuk: Teller of the Awful Truth, TTME.com.

- ↑ Hardtalk in Turkey: Orhan Pamuk, BBC News.

- ↑ Tavernise, Sabrina. 13 Arrested in Push to Stifle Turkish Ultranationalists Suspected in Political Killings. The New York Times. January 28, 2008.

- ↑ Plot to kill Orhan Pamuk foiled. The Times of India. 25 Jan 2008

- ↑ Lea, Richard. 'Plot to kill' Nobel laureate. The Guardian. January 28, 2008.

- ↑ 2006 Nobel Prize-winner Orhan Pamuk to receive Washington University's inaugural Distinguished Humanist Medal Nov. 27

- ↑ Turkish Author Receives Honorary Degree from Georgetown's "University News On-line

- ↑ Freie Universität Berlin Pressemitteilung (German)

- ↑ Tilburg University honours Michael Ignatieff, Orhan Pamuk and Robert Sternberg with doctorates [2] nuffic.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Lea, Richard. 'Plot to kill' Nobel laureate. The Guardian. January 28, 2008. OCLC 44669620

- Stocke, Joy E.; "The Melancholy Life of Orhan Pamuk," Wild River Review, November 19, 2007. ISSN 1932-362X

- Updike, John. "Anatolian Arabesques: A modernist novel of contemporary Turkey," The New Yorker, August 30, 2004. ISSN 0028-792X

External links

All links retrieved November 17, 2022.

- Orhan Pamuk official website

- The Guardian on Orhan Pamuk

- Biography, books and interviews in Turkish

- How to pronounce Orhan Pamuk

- Orhan Pamuk on the Nobel Prize website

- "My Father's Suitcase" - Orhan Pamuk's Nobel Lecture, 2006 as translated from the Turkish by Maureen Freely

- Turning Novel Ideas Into Inhabitable Worlds the subtitle reads: "Orhan Pamuk, Honored by Georgetown, Speaks of a Power Inherent on the Page" (from the Washington Post on-line Tuesday, October 30, 2007)

- A life in writing "Between two worlds" the subtitle reads: "Last year's Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk has faced criminal charges and even death threats in his native Turkey, yet he refuses to be disillusioned about the country's future" from the Guardian Unlimited on-line 8 December 2007. Maya Jaggi. Saturday December 8, 2007

|

2001: V. S. Naipaul | 2002: Imre Kertész | 2003: John Maxwell Coetzee | 2004: Elfriede Jelinek | 2005: Harold Pinter | 2006: Orhan Pamuk | 2007: Doris Lessing | 2008: J. M. G. Le Clézio | 2009: Herta Müller | 2010: Mario Vargas Llosa | 2011: Tomas Tranströmer | 2012: Mo Yan | 2013: Alice Munro | 2014: Patrick Modiano | 2015: Svetlana Alexievich | 2016: Bob Dylan | 2017: Kazuo Ishiguro | 2018: Olga Tokarczuk | 2019: Peter Handke | 2020: Louise Glück | 2021: Abdulrazak Gurnah | 2022: Annie Ernaux | 2023: Jon Fosse | |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.