Paris Peace Conference, 1919

The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 was a conference organized by the victors of World War I to negotiate the peace treaties between the Allied and Associated Powers and the defeated Central Powers, that concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles. The conference opened on January 18, 1919 and lasted until January 21, 1920 with a few intervals. It operated, while it lasted, as a world government [1]. Much of the work of the Conference involved deciding which of the Allied powers would administer territories formerly under German and Ottoman rule, introducing the concept of "trusteeship" into international law - territories considered unable to govern themselves are entrusted to another state, whose mandate is to build the nation, creating the necessary foundations for self-determination and independence. Most of the decisions of which power received which territory, however, had already been made, for example, by the Sykes-Picot Agreement of May 16, 1917[2]. As MacMillan points out, no one thought to consult the people of these territories about how they wished to be governed, with very few exceptions[3] The results of this division of territory continues to impact the world today since it resulted in the British Mandate of Palestine and in the creation of Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Jordan as nation states.

The Conference also imposed huge reparations on Germany. Some countries, such as France wanted to impose more sanctions but neither the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, or the U.S. President, Woodrow Wilson, wanted to cripple Germany. Most historians argue, however, that the sanctions humiliated Germany and placed too great an economic burden on the country, making, as Lloyd George predicted, another war inevitable.

The League of Nations was established at the Conference, the first attempt at an international intergovemental organization, with a brief to prevent war, settle disputes and improve peoples' lives across the globe. Just as World War I was believed by many to be the war that would end all war, so the Conference was meant to bring lasting peace. Unfortunately, it sowed seeds that resulted not only in World War II but in subsequent conflicts such as the Lebanese Civil War and the Arab-Israeli Conflict. Much was said about the need to protect minorities and create a more just world, but much of the business of the Conference involved nations protecting their own interests and trying to undermine those of others, such as the British vis-à-vis the French. Koreans, living under Japanese colonialism, for example, soon realized, after several Korean leaders traveled to Paris, that Wilson meant self-determination for former colonies of European powers, not existing colonies of Japan.

Nor did they choose to grant their creation, the League of Nations, enough authority to become an effective tool, and having masterminded it, Wilson could not persuade his country to join, despite heroic efforts [4] Wilson wanted the people of the territories whose governance was being decided to have a say in their future. This was included in the terms of mandates but hardly any consultation took place prior to the Mandates being agreed upon.

Overview

The following treaties were prepared at the Paris Peace Conference:

- Weimar Republic of Germany (Treaty of Versailles, 1919, June 28, 1919),

- Austria (Treaty of Saint-Germain, September 10, 1919),

- Bulgaria (Treaty of Neuilly, November 27, 1919),

- Hungary (Treaty of Trianon, June 4, 1920), and the

- The Ottoman Empire (Treaty of Sèvres, August 10, 1920; subsequently revised by the Treaty of Lausanne, July 24, 1923).

Also considered was the "holy grail" of Palestine, the Faisal-Weizmann Agreement (January 3, 1919). The Paris peace treaties, together with the accords of the Washington Naval Conference of 1921-1922, laid the foundations for the so-called Versailles-Washington system of international relations. The remaking of the world map at these conferences gave birth to a number of critical conflict-prone international contradictions, which would become one of the causes of World War II.

The decision to create the League of Nations and the approval of its Charter both took place during the conference.

The 'Big Four'—Georges Clemenceau, Prime Minister of France; David Lloyd George, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom; Woodrow Wilson, President of the United States of America; and Vittorio Orlando, Prime Minister of Italy—were the dominant diplomatic figures at the conference. The conclusions of their talks were imposed on the defeated countries.

Participants

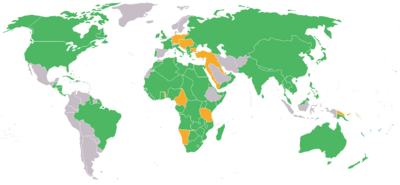

The countries that did take part were:

- Canada

- France

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Italy

- Japan

- Belgium

- Brazil

- Dominions of the British Empire (Canada, Australia, Union of South Africa, New Zealand, Newfoundland)

- Greece

- Guatemala

- Haiti

- Hejaz (now part of Saudi Arabia)

- Honduras

- Republic of China

- Cuba

- Yugoslavia

- Liberia

- Nicaragua

- Panama

- Poland

- Portugal

- Romania

- Siam (now Thailand)

- Czechoslovakia

Germany and its former allies were not allowed to attend the conference until after the details of all the peace treaties had been elaborated and agreed upon. The Russian SFSR was not invited to attend.

Ireland sent representatives in the hope of achieving self-determination and legitimizing the Republic declared after the Easter Rising in 1916 but had little success.

Prime Minister Borden fought successfully for Canada to have its own seat at the Conference; Canada was no longer simply represented by Britain. He also insisted that he be included among those leaders to sign the Treaty of Versailles.

Reparations

Germany was required, under the terms of the treaty of surrender, to accept full responsibility for the war. Germany was to pay 132 billion gold marks to the victors. Large tracts of Germany were to be de-industrialized and turned over to agriculture instead. Germany's allies were also charged with reparation. Germany was also to be demilitarized. However, in their case the amounts were never agreed nor were any sums ever collected. The U.S., which did not ratify the treaty, waived receipt of any payments. When Germany defaulted in 1923, French and Belgium troops occupied part of her territory. The amount owed was twice adjusted because Germany had difficulty making payments (1924 and 1929). Adolf Hitler repudiated the debt but post World War II reparations were resumed (in 1953).

The Mandate System

The Paris Peace Conference entrusted the colonies and territories of Germany and Turkey to the trusteeship of the victorious Allies under mandates from the League of Nations. These territories and their peoples were considered to be held as a "sacred trust of civilization" by the countries that were given the responsibility to govern them and to prepare them for eventual self-government. Each mandatory country was required to report annually to the League. Mandates were of three categories:

Class A were former territories of the Ottoman Empire considered almost ready to be recognized as nation states but which required the advice and assistance of a mandatory authority in the short term. These included Iraq and Jordan. These territories had not existed as distinct political units under the Ottomans and their borders were largely determined by colonial interests. Little attention was paid as to whether they were viable units in terms of local rivalries or different community interests, ignoring suggestions made by the British Arabist T. E. Lawrence.

Class B were former German colonies considered to require longer term oversight, with the mandatory authority exercising more control and power. These included Tanganyika (now Tanzania), which went to Britain, and the Cameroons, which were split between France and Britain.

'Class C' were also former German colonies but these were to be governed as more or less an integral part of the territory of the mandated nation. For example, German New Guinea (which was merged with the former British colony of Papua and was already administered by Australia) became an Australia trusteeship.

The Jewish delegation

Palestine, because of support for creating a Jewish homeland within at least part of the territory, was given a separate mandate with specific objectives. The Balfour Declaration which, after the Conference was addressed by representative of the World Zionist Organization, including its President, Chaim Weizmann, later first President of the State of Israel, was ratified by the delegates, committed the League to establish in Palestine "a national home for the Jewish people." Palestine was mandated to British governance, although the mandate was not finalized until 1922 [5]. The mandate also obliged Britain to ensure "that the rights and position of other sections of the population are not prejudiced" (Article 6). This mandate was bitterly opposed by the Arab world, represented at Paris by Emir Faisal, son of Sharif Hussein bin Ali (1853-1931) whose family had ruled the Hejaj since 1201 (see below). Ironically, since Arabs and Jews were both represented at the Peace Conference, the issues between these two people, deriving from rival territorial claims, remain unsolved.

Australian approach

The Australian delegates were Billy Hughes (Prime Minister), and Joseph Cook (Minister of the Navy), accompanied by Robert Garran (Solicitor-General). Their principal aims were war reparations, annexation of German New Guinea and rejection of the Japanese racial equality proposal. Hughes had a profound interest in what he saw as an extension of the White Australia Policy. Despite causing a big scene, Hughes had to acquiesce to a class C mandate for New Guinea.

Japanese approach

The Japanese delegation was headed by Saionji Kimmochi, with Baron Makino Nobuaki, Viscount Chinda Sutemi (ambassador in London), Matsui Keishiro (ambassador in Paris) and Ijuin Hikokichi (ambassador in Rome) and others making a total of 64. Neither Hara Takashi (Prime Minister) nor Yasuya Uchida (Foreign Minister) felt able to leave Japan so quickly after their election. The delegation focused on two demands: a) the inclusion of their racial equality proposal and b) territorial claims for the former German colonies: Shandong (including Jiaozhou Bay) and the Pacific islands north of the Equator i.e., the Marshall Islands, Micronesia, the Mariana Islands, and the Carolines. Makino was de facto chief as Saionji's role was symbolic, limited by ill-health. The Japanese were unhappy with the conference because they got only one half of the rights of Germany, and walked out of the conference.

The racial equality proposal

After the end of its international seclusion, Japan suffered unequal treaties and dreamed of obtaining equal status with the Great Powers. In this context, the Japanese delegation to the Paris peace conference proposed the racial equality proposal. The first draft was presented to the League of Nations Commission on February 13 as an amendment to Article 21:

The equality of nations being a basic principle of the League of Nations, the High Contracting Parties agree to accord as soon as possible to all alien nationals of states, members of the League, equal and just treatment in every respect making no distinction, either in law or in fact, on account of their race or nationality.

It should be noted that the Japanese delegation did not realize the full ramifications of their proposal, and the challenge its adoption would have put to the established norms of the (Western dominated) international system of the day, involving as it did the colonial subjugation of non-white peoples. In the impression of the Japanese delegation, they were only asking for the League of Nations to accept the equality of Japanese nationals; however, a universalist meaning and implication of the proposal became attached to it within the delegation, which drove its contentiousness at the conference.[6]

The proposal received a majority vote on April 28, 1919. Eleven out of the 17 delegates present voted in favor to its amendment to the charter, and no negative vote was taken. The chairman, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, overturned it saying that although the proposal had been approved by a clear majority, that in this particular matter, strong opposition had manifested itself, and that on this issue a unanimous vote would be required. This strong opposition came from the British delegation. Though in a diary entry by House it says that President Wilson was at least tacitly in favor of accepting the proposal, in the end he felt that British support for the League of Nations was a more crucial objective. There is not much evidence that Wilson agreed strongly enough with the proposal to risk alienating the British delegation over it. It is said that behind the scenes Billy Hughes and Joseph Cook vigorously opposed it as it undermined the White Australia Policy. Later, as conflicts between Japan and America widened, the Japanese media reported the case widely—leading to a grudge toward the U.S. in Japanese public opinion and becoming one of the main pretexts of Pearl Harbor and World War II.

As such, this point could be listed among the many causes of conflict which lead to World War II, which were left unaddressed at the close of World War I. It is both ironic and indicative of the scale of the changes in the mood of the international system that this contentious point of racial equality would later be incorporated into the United Nations Charter in 1945 as the fundamental principle of international justice.

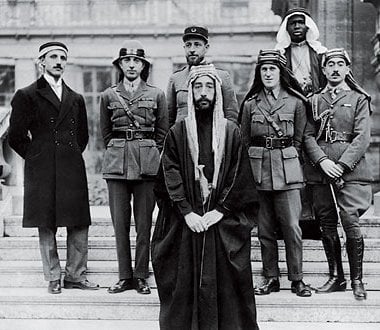

The Arab delegation

An Arab delegation at Paris was led by Emir Faisal, with Colonel T. E. Lawrence as interpreter. Lawrence was officially employed by the British Foreign Office but acted as if he were a full member of the Arab delegation, wearing Arab dress. During World War I, he had recruited an Arab Legion to fight against the Ottomans with the support of Faisal's father, King Hussein, in return for assurances that an Arab state would be established in the remnants of the Ottoman Empire. The geographical extent of this territory was never finalized, but Hussein himself assumed it would stretch from the Hejaz north, including the Ottoman province of Greater Syria, which included Palestine, Trans-Jordan as well as part of Iraq. While the Lebanon was also in Greater Syria, it was understood that the French would assume responsibility for this territory and that some areas would be entrusted to the British. No official treaty existed but the offer was confirmed in correspondence from Sir Henry McMahon (1862-1949), Britain's High Commissioner in Egypt[7]

The Balfour Declaration came as a shock to the Arab leader, since this promised the Jews a homeland in the middle of what he assumed would be an Arab state. Also, the Sykes-Picot Agreement of May 16, 1916 between the British and the French allocated territory to the two powers with no reference to an Arab state. While Hussein expected to be given Syria, the Agreement entrusted Syria to the French. However, Emir Faisal presented the Arab case at the Conference, even though his very presence there was resented by the French, who did not see why Arabs should be represented. Woodrow Wilson was sympathetic to the Arab cause but did not want the U.S. to administer a mandate in the Middle East, which might have occurred had the Conference agreed to the Arab proposal. Lawrence did his best to persuade delegates to support the Arabs but may have alienated some because of his disregard for protocol - officially, he was present as an interpreter. In 1918, before leaving for the Conference, he had presented an alternative map of the region which included a Kurdish state and boundaries based on local sensitivities rather than on imperial interests. The borders of the British-French map were determined by existing commercial concessions, known as "capitulations." The final division did not deliver the Arab state as such. The British, however, established Faisal as king of Iraq and his brother as king of Jordan, which they carved from out of their Mandate of Palestine. Hussein was free to declare the Hejaz independent (it had been under the Ottomans) but he fell to a coup led by Prince Abdul Aziz bin Saud in 1924, founder of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Lawrence, although bitterly disappointed by the Conference's outcome, was instrumental in establishing the kingdoms of Iraq and Jordan. [8]

Territorial claims

The Japanese claim to Shandong was disputed by the Chinese. In 1914 at the outset of First World War Japan had seized the territory granted to Germany in 1897. They also seized the German islands in the Pacific north of the equator. In 1917, Japan had made secret agreements with Britain, France and Italy as regards their annexation of these territories. With Britain, there was a mutual agreement, Japan also agreeing to support British annexation of the Pacific islands south of the equator. Despite a generally pro-Chinese view on behalf of the American delegation, Article 156 of the Treaty of Versailles transferred German concessions in Shandong, China to Japan rather than returning sovereign authority to China. Chinese outrage over this provision led to demonstrations known as the May Fourth Movement and China's eventual withdrawal from the Treaty. The Pacific islands north of the equator became a class C mandate administered by Japan.

Italy's approach

Italy had been persuaded first to join the Triple Alliance and then to join the Allies in order to gain land. In the Treaty of London, 1915, they had been offered the Trentino and the Tyrol as far as Brenner, Trieste and Istria, all the Dalmatian coast except Fiume, full ownership of Albanian Vallona and a protectorate over Albania, Aladia in Turkey and a share of Turkish and German Empires in Africa.

Vittorio Orlando was sent as the Italian representative with the aim of gaining these and as much other territory as possible. The loss of 700,000 Italians and a budget deficit of 12,000,000,000 Lire during the war made the Italian government and people feel entitled to these territories. There was an especially strong opinion for control of Fiume, which they believed was rightly Italian due to the Italian population.

However, by the end of the war the allies had made contradictory agreements with other nations, especially in Central Europe and the Middle-East. In the meetings of the "Big Four" (in which his powers of diplomacy were inhibited by his lack of English) the Great Powers were only willing to offer Trentino to the Brenner, the Dalmatian port of Zara, the Island of Lagosta and a couple of small German colonies. All other territories were promised to other nations and the great powers were worried about Italy's imperial ambitions. As a result of this Orlando left the conference in a rage.

United Kingdom's approach

Maintenance of the British Empire's unity, holdings and interests were an overarching concern for the United Kingdom's delegates to the conference, but it entered the conference with the more specific goals of:

- Ensuring the security of France

- Settling territorial contentions

- Supporting the Wilsonian League of Nations

with that order of priority.

The Racial Equality Proposal put forth by the Japanese did not directly conflict with any of these core British interests. However, as the conference progressed the full implications of the Racial Equality Proposal, regarding immigration to the British Dominions (specifically Australia), would become a major point of contention within the delegation.

Ultimately, Britain did not see the Racial Equality proposal as being one of the fundamental aims of the conference. The delegation was therefore willing to sacrifice this proposal in order to placate the Australian delegation and thus help satisfy its overarching aim of preserving the unity of the British Empire. [9]

United States' approach

After Woodrow Wilson failed to convince Lloyd George and Georges Clemenceau to support his Fourteen Points, the conference settled on discussing the possibility of a League of Nations. After most points were agreed on, the written document detailing the League was brought back to the U.S. to be approved by Congress. Congress objected only to Article 10, which stated that an attack on any member of the League would be considered an attack on all members, who would be expected to support, if not join in on the attacked country's side. Wilson, disheartened, returned to Paris in March after all the diplomats had reviewed the League outline with their respective governments. Without the approval of Congress, Clemenceau noted Wilson's weak position and furthered the interests of Britain and France, opposed by Wilson. Germany was forced to accept full blame, which the new German government disliked. Germany was being asked to accept all responsibility, lose all colonies and some homeland, and to pay war reparations to the Allies of World War I US$32 billion or 133 billion gold marks; later reduced to 132 billion marks. Wilson would not sign these treaties, and so the United States signed separate treaties with Germany, approved by Congress.

Notes

- ↑ Margaret MacMillan. Peacemakers: Six months that changed the world. (London: John Murray, 2001), 485

- ↑ About War: Official Documents "15 & 16 May, 1916: The Sykes-Picot Agreement," The Sykes-Picot Agreement Transcriptions. 1916 Documents. Brigham Young University Library. Retrieved May 12, 2007

- ↑ MacMillan, 104

- ↑ see Danderson Beck, "Wilson and the League of Nations," Wilson and the League of Nations San.Beck.org. This article includes the 14 points presented by Wilson at Paris which set out his vision for peace, and the five principles that informed the Covenant of the League of Nations. Retrieved 13 May 2007. Beck describes Wilson's heroic effort to convince the US Congress to ratify the Covenant. Although the US did not join, under the terms of the Covenant, Wilson convoked the League’s first meeting.

- ↑ "The Palestine Mandate of the League of Nations, 1922," Mideast Web The Palestinian Mandate of the League of Nations, 1922 Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- ↑ Naoko Shimazu. Japan, Race and Equality: The Racial Equality Proposal of 1919. (Nissan Institute Routledge Japanese Studies Series) (London: Routledge, 1998), 115.

- ↑ The Hussein-McMahon Correspondence, Jewish Virtual Library The Hussein-McMahon Correspondence Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- ↑ C. T. Evans, and A. Clubb, "T.E. Lawrence and the Arab Cause at the Paris Peace Conference," Northern Virginia Community College T. E Lawrence and the Arab Cause at the Paris Peace Conference" Retrieved May 12, 2007.

- ↑ Shimazu, 1998, 14-15, 117

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boemeke, Manfred F., Gerald D. Feldman, and Elisabeth Gläser. The Treaty of Versailles: A Reassessment After 75 Years. Publications of the German Historical Institute, ISBN 9780521621328

- Goldberg, George. The Peace to End Peace: The Paris Peace Conference of 1919. New York, Harcourt, Brace & World, 1969. ISBN 0151715688

- Jackson, Hampden J. The Post-War World: A Short Political History: 1918-1934. Boston, MT: Little, Brown & Co, [1935]. republished 1939. ASIN: B00085AXDQ

- MacMillan, Margaret. Peacemakers: Six months that changed the world.', London: John Murray, 2001. ISBN 0719562376

- Shimazu, Naoko. Japan, Race and Equality: The Racial Equality Proposal of 1919. (Nissan Institute Routledge Japanese Studies Series) NY: ; London: Routledge, 1998. ISBN 0415172071

- Otte, T. G. and Margaret Macmillan. 2001. "Peacemakers - The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 and Its Attempt to End War." TLS, the Times Literary Supplement. No. 5143: 3.

External links

All links retrieved November 18, 2022.

- Foreign Affairs: Paris Peace Conference at US History.com

- T E Lawrence's Middle East Vision at NPR includes Lawrence's "peace map," an alternative division of the region taking note of local loyalties and sensitivities. National Public Radio.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.