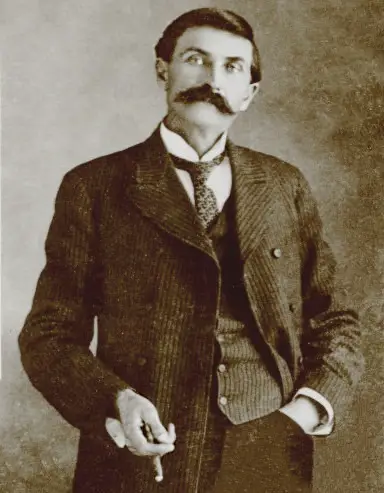

Pat Garrett

| Pat Garrett | |

| |

| Born | June 5, 1850 |

|---|---|

| Died | February 28, 1908 |

| Cause of death | Murder |

| Other names | Patrick Garrett |

Patrick "Pat" Floyd Garrett (June 5, 1850 – February 28, 1908) was an American Old West lawman, bartender, and customs agent who was most known for killing Billy the Kid.[1] Although he held a number of law enforcement posts and gained a reputation for his skill in bringing in wanted men, he squandered his earnings in gambling and drinking. He was shot to death February 28, 1908 possibly by outlaws, although debate continues about the circumstances of his death and the identity of his killer.

The popularity Garrett had initially enjoyed for killing Billy the Kid decreased as the Kid's mythic status increased. His failure to give The Kid a chance to surrender was regarded as unfair. For a while, he enjoyed the patronage of President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt's own penchant for frontier life—he himself had hunted down three outlaws while acting as a deputy sheriff—attracted him to Garrett. However, Garrett's drunkenness as well as controversy surrounding the killing of The Kid quickly disillusioned him. Garrett nonetheless remains symbolic of an era when only a thin line separated the lawmen from the outlaws they policed. At the time, the rich were considered by many to have robbed the poor in order to accumulate their wealth and some outlaws were popular because they targeted the rich. Garrett, on the other hand, targeted a popular outlaw.

Early life

Patrick Floyd Garrett was born in Chambers County, Alabama (near present-day Cusseta, Alabama). He grew up on a prosperous Louisiana plantation near Haynesville, Louisiana in northern Claiborne Parish, just below the Arkansas state line where he moved at age six after his father, John L. Garrett, purchased this and another cotton plantation (Chamberlain 1999, 54). He left home in 1869 and found work as a cowboy in Dallas County, Texas.

In 1875, he left to hunt buffalo. In 1878, Garrett shot and killed a fellow hunter who charged at Garrett with a hatchet over a disagreement over buffalo hides. Upon dying, the hunter brought Garrett to tears by asking him to forgive him.

Garrett moved to New Mexico and briefly found work as a cowpuncher before quitting to open his own saloon. A tall man, he was referred to by locals as "Juan Largo" or "Big John." In 1879, Garrett married Juanita Gutierrez (or Martinez) (Chamberlain 1999, 55), who died within a year. In 1880, he married Apolonaria Gutierrez. The couple had nine children.

Lincoln County War

On November 7, 1880, the sheriff of Lincoln County, New Mexico, George Kimbell, resigned with two months left in his term. As Kimbell's successor, the county appointed Garrett (a member of the Republican Party who ran as a Democrat), a gunman of some reputation who had promised to restore law and order. Garrett was charged with tracking down and arresting a friend from his saloon-keeping days, Henry McCarty, a jail escapee and Lincoln County War participant who often went by the aliases Henry Antrim and William Harrison Bonney, but is better known as "Billy the Kid." McCarty was an alleged murderer who had participated in the Lincoln County War. He was said to have killed 21 men, one for every year of his life, but the actual total was probably closer to nine. New Mexico Governor Lew Wallace had personally put a $500 reward on McCarty's capture.

During a December 19 shootout, Garrett killed Tom O'Folliard, a member of McCarty's gang, with a shot to the stomach (Chamberlain 1999, 57). A few nights later, the sheriff's posse killed an unarmed Charlie Bowdre, captured The Kid and his companions, and transported the captives to Mesilla, New Mexico, for trial. Though he was convicted, The Kid managed to escape from jail on April 18, 1881, after killing his guards, J. W. Bell and Bob Olinger.

On July 14, 1881, Garrett visited Fort Sumner to question a friend of The Kid's about the whereabouts of the outlaw. He learned that The Kid was staying with a mutual friend, Pedro Maxwell. Around midnight, Garrett went to Maxwell's house. The Kid was asleep in another part of the house but woke up hungry in the middle of the night and entered the kitchen where Garrett was standing in the shadows. The Kid did not recognize the man standing in dark. "Quien es (Who is it)? Quien es?" The Kid asked repeatedly. Garrett replied by shooting at The Kid twice, the first shot hitting him in the heart, and the second one did not hit him. (Some historians have questioned Garrett's account of the shooting, alleging the incident happened differently. They claim that Garrett went into Paulita Maxwell's room and tied her up. The Kid walked into her room, and Garrett ambushed him with a single blast from his Sharps rifle.)

There has been much dispute regarding whether or not Pat Garrett actually did kill Billy the Kid. The way Garrett allegedly killed McCarty without warning eventually sullied the lawman's reputation. Garrett claimed that Billy the Kid had entered the room armed with a pistol, but no gun was found on his body. Other accounts claim he entered carrying a kitchen knife. There is no hard evidence to support this; however, if he did so it is likely he intended to cut some food for himself, since he had no idea anyone was waiting for him. Regardless of how he died, Billy was a wanted criminal, and so sheriff Garrett chose not to give him a chance to surrender.

Still, at the time the shooting solidified Garrett's fame as a lawman and gunman, and led to numerous appointments to law enforcement positions, as well as requests that he pursue outlaws in other parts of New Mexico (Utley 1989, 193–96).

After the Lincoln County War

His law enforcement career never achieved any great success following the Lincoln County War, and he mostly used that single era in his life as his stepping-stone to higher positions. After finishing out his term as sheriff, Garrett became a rancher and released a book ghostwritten by his friend Ashmun "Ash" Upson in 1882 about his experiences with McCarty. The book contained some false information and turned out to be a huge failure (Chamberlain 1999, 60–61). However, he was not reelected as Lincoln County sheriff in 1882 and was never paid the $500 reward for McCarty's capture, since he had allegedly killed him. In 1884, he lost an election for the New Mexico State Senate. Later that year, he left New Mexico and helped found and captain a company of Texas Rangers.

He returned to New Mexico briefly in 1885. In October 1889, Garrett ran for Chaves County, New Mexico, sheriff but lost. By this time, his rough disposition was beginning to wear thin with much of the populace, and rumors of his less than admirable killing of Billy the Kid were beginning to affect his popularity. Garrett left New Mexico in 1891 for Uvalde, Texas. He returned to New Mexico in 1896 to investigate the disappearance of Albert Jennings Fountain and Fountain's young son Henry.

Disappearance of Albert Jennings Fountain

In January 1896, Colonel Fountain served as a special prosecutor against men charged with cattle rustling in Lincoln, New Mexico. With his work finished, Fountain left Lincoln with his eight-year-old son Henry. The two did not complete their trip home. On the third day they disappeared near White Sands, New Mexico.

Fountain's disappearance caused outrage throughout the territory. Further complicating matters was the fact that the main suspects in the disappearance were deputy sheriffs William McNew, James Gililland, and Oliver M. Lee. New Mexico's governor saw that outside help was needed, and he called in Pat Garrett. One problem Garrett encountered was the fact that Lee, McNew, and Gililland were very close with powerful ex-judge, lawyer, and politician Albert B. Fall (Chamberlain 1999, 63).

Garrett, who was appointed Doña Ana County sheriff on August 10, 1896, and elected to the post on January 4, 1897, believed that he would never get a fair showing with Fall in control of the courts. Therefore, Garrett waited two full years before presenting his evidence before the court and securing indictments against the suspected men. McNew was quickly arrested, and Lee and Gililland went into hiding.

Garrett's posse caught up with Lee and Gililland on July 12, 1898. One of Garrett's deputies, Kurt Kearney, was killed in the gun battle that followed. Garrett and his posse then retreated, and Gililland and Lee escaped. Lee and Gililland later surrendered, although not to Garrett. Both stood trial and were acquitted. The location of the Fountain bodies remains a mystery (Chamberlain 1999, 64).

Final years

By 1899 Garrett was a regular gambler, owing money to various parties, and an alcoholic (Chamberlain 1999, 64). On December 20, 1901, Theodore Roosevelt, who became a personal friend of Garrett's, appointed him customs collector in El Paso, Texas. Garrett served for five years. However, he was not reappointed, possibly because he had embarrassed Roosevelt by showing up at a San Antonio, Texas Rough Riders reunion with a notorious gambler friend named Tom Powers. Garrett had Powers pose in a group photograph with Roosevelt, resulting in bad publicity for the president.

Garrett had been warned by friends about his close association with Powers. Years earlier, Powers had been run out of his home state of Wisconsin for beating his father into a coma. Garrett did not listen, and when his reappointment was denied, he traveled to Washington, D.C., to speak personally with Roosevelt. He had the bad judgment of taking Powers with him. In that meeting, Roosevelt told Garrett plainly that there would be no reappointment.

Garrett retired to his ranch in New Mexico but was suffering financial difficulties. He owed a large amount in taxes and was found liable for an unpaid loan he had co-signed for a friend. Garrett borrowed heavily to make these payments and started drinking and gambling excessively. He crossed paths regularly with Oliver Lee and Lee's corrupt attorney Albert Fall, always finding himself on the opposite end of their illegal land deals and the intimidation of local ranchers and citizens (Chamberlain 1999, 65–66).

Shooting death

Garrett's main creditor, a rancher named W. W. Cox, worked out a deal to repay the debt by using Garrett's quarter horse ranch in the San Andres Mountains slopes as grazing land for one of his partners. (There is no record of the deal in the courthouse, and no deed from Garrett to Cox.) Cox took the ranch house and razed it. Garrett's son, Pat, Jr., kept the upper ranch with the water supply until his death. Garrett agreed to the deal, not realizing Jesse Wayne Brazel would be grazing goats rather than cattle on the land. Garrett objected to the goats, feeling their presence lowered the value of his land in the eyes of buyers or other renters. By this time, questions surrounding both the manner in which he killed Billy the Kid and Garrett's general demeanor had led to his becoming quite unpopular. He no longer had any local political support, his support by President Roosevelt having been withdrawn, and he had few friends with power.

Garrett and a man named Adamson, who was in the process of talks with Garrett to purchase land, rode together heading from Las Cruces in Adamson's wagon. Brazel showed up on horseback along the way. Garrett and Brazel began to argue about the goats grazing on Garrett's land. Garrett is alleged to have leaned forward to pick up a shotgun on the floorboard. Brazel shot him once in the head, and then once more in the stomach as Garrett fell from the wagon. Brazel and Adamson left the body by the side of the road and returned to Las Cruces, alerting Sheriff Felipe Lucero of the killing (Chamberlain 1999, 66).

Debate

There has occasionally been disagreement about the identity of Pat Garrett's killer. Today, most historians believe Jesse Wayne Brazel, who confessed to the shooting and was tried for first-degree murder, did in fact commit the crime. Cox paid his bond and retained Albert B. Fall as his defense attorney. Brazel claimed self defense, claiming that Garrett was armed with a shotgun and was threatening him. Adamson backed up Brazel's story. The jury took less than a half-hour to return a not-guilty verdict. Cox hosted a barbecue in celebration of the case's outcome.

Another alleged suspect in Garrett's death was the outlaw Jim Miller, a known "killer for hire" and cousin of Adamson. Miller was alleged to have been hired by enemies of Garrett. But this is believed to be a rumor because Adamson was kin to him, and Miller is believed to have been in Oklahoma at the time. Oliver Lee was also alleged to have taken part in a conspiracy to kill Garrett, made up of businessmen and outlaws who disliked the former lawman. However, despite his previous clashes with Garrett, there is no evidence to support the claim. Lee had previously avoided Garrett at every opportunity and was believed to have been afraid of Garrett.

To date, common consensus is that the killing happened as Brazel said it had. Garrett was known to have carried a double-barreled shotgun when he traveled, and he had a fiery temper. Garrett could have reacted violently during his argument with Brazel. Others have argued in favor of another course of events, in which Garrett had had a confrontation with Brazel while on a wagon ride with Brazel and Adamson and was shot while preparing to urinate at the back of the stopped wagon (Chamberlain 1999, 67).

Funeral and burial site

Garrett's body was too tall for any pre-made coffins in town, so a special one had to be shipped in from El Paso. His funeral service was held March 5, 1908, and he was laid to rest next to his daughter, Ida, who had preceded him in death eight years earlier.

The site of Garrett's death is now commemorated by a historical marker, which can be visited off to the south of U.S. Route 70, between Las Cruces, New Mexico and the San Augustin Pass.

The highway marker is not at the actual spot where Garrett was shot. The location of the shooting was marked by Pat's son Jarvis Garrett in 1938–1940 with a monument of his construction. The monument consists of cement laid around a stone with a cross carved in it. It is believed that the cross is the work of Pat’s mother. Scratched in the cement is "P. Garrett" and the date of his killing.

The location of this marker has been a fairly closely kept secret, but is now being made public because the city of Las Cruces is annexing the land where the marker is located. An organization called Friends of Pat Garrett has been formed to ensure that the city preserves the site and marker.

Garrett's grave and the many graves of his descendants can be found in Las Cruces at the Masonic Cemetery.

Legacy

Portrayals in film

Garrett has been a recurring character in movies and television shows, and has been portrayed on screen by actors Wallace Beery (1930), Thomas Mitchell (1943), John Dehner (1957), Barry Sullivan (1960), Glenn Corbett (1970), James Coburn (1973), Patrick Wayne (1988), Duncan Regehr (1989), and William Petersen (1990). The Barry Sullivan portrayal was in an NBC half-hour western series The Tall Men, costarring Clu Gulager as The Kid.

Notes

- ↑ The term "American Old West" refers to the stories, myths, and legends about life in the American West from about 1865 until the end of the nineteenth century, sometimes extended into the start of the twentieth.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chamberlain, Kathleen. 1999. "Pat Floyd Garrett—The Man Who Shot Billy the Kid." In With Bullets and Badges: Lawmen and Outlaws in the Old West, edited by Richard W. Etulain and Glenda Riley (Golden: Fulcrum Publishing), 53–69. ISBN 9781555914332

- Trachtman, Paul. 1974. The Old West: The Gunfighters. Alexandria: Time-Life Books.

- Utley, Robert M. 1989. Billy the Kid: A Short and Violent Life. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803245532

External links

All links retrieved November 18, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.