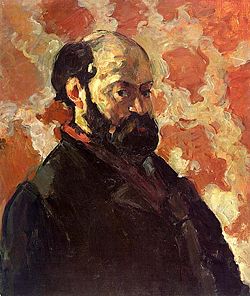

Paul Cézanne (January 19, 1839 – October 22, 1906) was a French artist, a post-impressionist painter whose work, along with the work of Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, laid foundations for the new and radically different world of modern art in the twentieth century. Cézanne is thought to have formed the bridge between late nineteenth-century impressionism and the early twentieth century's new line of artistic inquiry, cubism. The line attributed to both Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso that Cézanne "...is the father of us all..." cannot be easily dismissed.

Cézanne's work demonstrates a mastery of design, color, composition, and draftsmanship. His often repetitive, sensitive, and exploratory brushstrokes are highly characteristic and clearly recognizable. Using planes of color and small brushstrokes that build up to form complex fields, at once both a direct expression of the sensations of the observing eye and an abstraction from observed nature, Cézanne's paintings convey intense study of his subjects, a searching gaze and a dogged struggle to deal with the complexity of human visual perception. Cézanne work was among that last of those painters who saw themselves as reflecting the beauty of God's creation.

Life and work

Biographical background

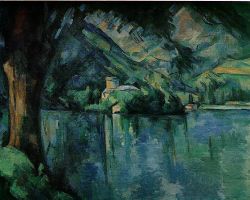

Paul Cézanne was born on January 19, 1839 in Aix-en-Provence, one of the southernmost regions of France. Provence is a varied and complex region geographically, comprised of several limestone plateaus and mountain ranges, to the east of the Rhône valley. The climate is hot and dry in summer and cool in winter. Altitudes range from lower-lying areas to some impressive mountain peaks. These mountainous areas have characteristic pine forests and limestone outcrops. Each of these topographical features would find prominent expression in Cézanne's work. Cézanne developed a lifelong love for the Provençal landscape, which became his chief subject before his later large scale works involving 'The Bathers' consumed him.

From 1859 to 1861 Cézanne studied law in Aix, while also receiving drawing lessons. Going against the objections of his banker father, Louis-Auguste Cézanne, Paul Cézanne committed himself to pursuing his artistic development and left Aix for Paris in 1861, with his close friend Émile Zola. Eventually, Cézanne and his father reconciled about his choice of career and later Cézanne received a large inheritance from his father, on which he could continue living comfortably.

Cézanne the artist

In Paris, Cézanne met the impressionists, including Camille Pissarro. Initially the friendship formed in the mid-1860s between Pissarro and Cézanne was that of master and mentor, with Pissarro exerting a formative influence on the younger artist. Over the course of the following decade, their landscape painting excursions together, in Louveciennes and Pontoise, led to a collaborative working relationship between equals.

Cézanne's early work is often concerned with the figure in the landscape and comprises many paintings of groups of large, heavy figures in the landscape, imaginatively painted. Later in his career, he became more interested in working from direct observation and gradually developed a light, airy painting style that was to influence the impressionists enormously. Nonetheless, in Cézanne's mature work we see the development of a solidified, almost architectural style of painting. Throughout his life, Cézanne struggled to develop an authentic observation of the seen world by the most accurate method of representing it in paint that he could find. To this end, he structurally ordered whatever he perceived into simple forms and color planes. His statement "I want to make of impressionism something solid and lasting like the art in the museums," and his contention that he was recreating Poussin "after nature" underscored his desire to unite observation of nature with the permanence of classical composition.

Optical phenomena

Cézanne's geometric forms was to influence Pablo Picasso's, Georges Braque's, and Juan Gris's cubism in profound ways. When one compares Cézanne's late oils with cubist paintings, a link of influence is most evident. The key to this link is the depth and concentration that Cézanne applied to recording his observations of nature, a focus later intellectually synthesized in cubism. People have two eyes and therefore possess binocular vision. This gives rise to two slightly separate visual perceptions, which are simultaneously processed in the visual cortex of the brain. This provides people with depth perception and a complex knowledge of the space in which they inhabit. The essential aspect of binocular vision that Cézanne employed and which became influential on cubism, was that people often "see" two views of an object at the same time. This led him to paint with a varying outline that shows the left-eye and the right-eye view at the same time, thus ignoring traditional linear perspective. Cubists like Picasso, Braque, and Gris took this a step further by experimenting with not only two simultaneous views, but with multiple views of the same subject.

Exhibitions and subjects

Cézanne's paintings were shown in the first exhibition of the Salon des Refusés in 1863, which displayed works not accepted by the jury of the official Paris Salon. The official Salon rejected Cézanne's submissions every year from 1864 to 1869.

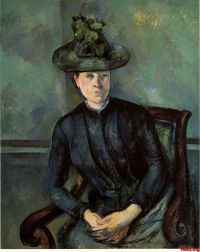

Cézanne exhibited little in his lifetime and worked in increasing artistic isolation, remaining in the south of France, in his beloved Provence, far from Paris. He concentrated on a few subjects and was equally proficient in each genre: landscapes, portraits, still lifes, and studies of bathers. For the last, Cézanne was compelled to design from his imagination, due to a lack of available nude models. Like his landscapes, his portraits were drawn from that which was familiar. His wife and son, local peasants, children, and his art dealer all served as subjects. His still lifes are decorative in design, painted with thick, flat surfaces, yet with a weight reminiscent of Gustave Courbet. The 'props' for his works are still to be found, as he left them, in his studio (atelier), in the suburbs of modern Aix.

Although religious images appeared less frequently in Cézanne's later work, he remained a devout Catholic and said “When I judge art, I take my painting and put it next to a God-made object like a tree or flower. If it clashes, it is not art.”

Death

In 1906, during a thunderstorm, Cézanne collapsed while painting outdoors. One week later, on October 22, he died of pneumonia.

Main periods of Cezanne's work

Various periods in the work and life of Cézanne have been defined.[1] Cézanne created hundreds of paintings, some of which command considerable market prices. On May 10, 1999, Cézanne's painting Rideau, Cruchon et Compotier sold for $60.5 million, the fourth-highest price paid for a painting at the time. In 2006, it was still the most expensive still life ever sold at an auction.

The dark period, Paris, 1861-1870

In 1863, Napoleon III created by decree the Salon des Refusés, at which paintings rejected for display at the Salon of the Académie des Beaux-Arts were to be displayed. The artists of the refused works were considered revolutionary. They included many young impressionists. Although influenced by their style, Cézanne was inept at social relations with them (he seemed rude, shy, angry and given to depression), which resulted in a brief dark period. Unlike either his earlier watercolors and sketches at the École Spéciale de dessin at Aix-en-Provence, in 1859 or his subsequent works, the words antisocial or violent are often used and the colors are darker.[2]

Impressionist period, Provence and Paris, 1870-1878

After the start of the Franco-Prussian War in July 1870, Cézanne and his mistress, Marie-Hortense Fiquet, left Paris for L'Estaque, near Marseilles, where he painted predominantly landscapes. He was declared a draft-dodger in January 1871, but the war ended in February and the couple moved back to Paris in the summer of 1871. After the birth of their son, Paul, in January 1872, they moved to Auvers in Val-d'Oise near Paris. Cézanne's mother was kept a party to family events, but his father was not informed of Fiquet for fear of risking his wrath. Cézanne received from his father an allowance of 100 francs.

Pissarro lived in Pontoise. There and in Auvers, he and Cézanne painted landscapes together. For a long time afterwards, Cézanne described himself as Pissarro's pupil, referring to him as "God the Father" and saying, "We all stem from Pissarro."[3] Under Pissarro's influence, Cézanne began to abandon the dark colors and his canvases grew much brighter.

Leaving Hortense in the Marseille region, Paul moved between Paris and Provence, exhibiting in the impressionist shows of Paris nearly every year until 1878. In 1875, he attracted the attention of the collector, Victor Chocquet, whose commissions provided some financial relief. Cézanne's exhibited paintings attracted ridicule, outrage, and sarcasm; for example, the reviewer Louis Leroy said of Cézanne's portrait of Chocquet: "This peculiar looking head, the colour of an old boot might give [a pregnant woman] a shock and cause yellow fever in the fruit of her womb before its entry into the world."[3]

In March 1878, Cézanne's father found out about his mistress, Marie-Hortense Fiquet, and threatened to cut Cézanne off financially, but instead, in September, he decided to give him 400 francs for his family. Cézanne continued to migrate between the Paris region and Provence until his father had a studio built for him at his home, Jas de Bouffan, in the early 1880s. This was on the upper floor and an enlarged window was provided, allowing in the northern light, but interrupting the line of the eaves. This feature remains today. Cézanne stabilized his residence in L'Estaque. He painted with Renoir there in 1882 and visited Renoir and Monet in 1883.

Mature period, Provence, 1878-1890

In the early 1880's, the Cezanne family stabilized their residence in Provence, where they remained, except for brief sojourns abroad, from then on. The move reflects a new independence from the Paris-centered impressionists and a marked preference for the south, Cézanne's native soil. Hortense's brother had a house within view of Mount St. Victoire at Estaque. A run of paintings of this mountain from 1880-1883 and others of Gardanne from 1885-1888, are sometimes known as "the Constructive Period."

The year 1886 was a turning point for the family. Cézanne married Hortense. She had long since been known politely as Madame Cézanne (Mrs. Cézanne). In that year also, Cézanne's father died, leaving him the estate purchased in 1859. Cézanne was 47. By 1888, the family was in the former manor, Jas de Bouffan, a substantial house and grounds with outbuildings, which afforded a new-found comfort. This house, with much-reduced grounds, is now owned by the city and is open to the public on a restricted basis.

Also in that year, Cézanne broke off his friendship with Émile Zola, after the latter used Cézanne, in large part, as the basis for the unsuccessful and ultimately tragic fictitious artist Claude Lantier, in the novel (L'Œuvre). Cézanne considered this a breach of decorum and a friendship begun in childhood was irreparably damaged.

Final period, Provence, 1890-1905

Cezanne's idyllic period at Jas de Bouffan was temporary. From 1890 until his death, he was beset by troubling events and he withdrew further into his painting, spending long periods as a virtual recluse. His paintings became well-known and sought after, and he was the object of respect from a new generation of painters.

His health problems began with diabetes in 1890, destabilizing his personality and straining his relationships with others. He traveled in Switzerland, with Hortense and his son Paul, perhaps hoping to restore their relationship. Cézanne, however, returned to Provence to live; Hortense and their son, to Paris. Financial need prompted Hortense's return to Provence, but in separate living quarters. Cézanne moved in with his mother and sister and in 1891 he turned to Catholicism.

Cézanne alternated between painting at Jas de Bouffan and in the Paris region, as before. In 1895, he made a germinal visit to Bibémus Quarries and climbed Mont Sainte-Victoire. The labyrinthine landscape of the quarries must have struck a note, as he rented a cabin there in 1897 and painted extensively from it. The shapes are believed to have inspired the embryonic 'cubist' style. Also in that year, his mother died, an upsetting event but one which made reconciliation with his wife possible. He sold the empty nest at Jas de Bouffan and rented a place on Rue Boulegon, where he built a studio. There is some evidence that his wife joined him there.

The relationship, however, continued to be stormy. He needed a place to be by himself. In 1901, he bought some land along the Chemin des Lauves ("Lauves Road"), an isolated road on some high ground at Aix, and commissioned a studio to be built there (the 'atelier', now open to the public). He moved there in 1903. Meanwhile, in 1902, he had drafted a will excluding his wife from his estate and leaving everything to his son Paul; the relationship was apparently off again. She is said to have burned the mementos of Cézanne's mother.

From 1903 to the end of his life, Cézanne painted in his studio, working for a month in 1904 with Émile Bernard, who stayed as a house guest. After his death it became a monument, Atelier Paul Cézanne, or les Lauves.

Legacy

Even though Cézanne did not enjoy much professional success during his life, he likely had the greatest impact out of any other artist on the next generation of modernist painters. Cézanne incorporated impressionism’s emphasis on direct observation in all of his works, but he was much more deliberate and constructive with his brushwork. Unlike the impressionists, who sought to capture fleeting qualities of light and atmosphere, Cézanne sought to make sense out of nature. He wanted to create something concrete and lasting from a surge of visual sensations. Some art critics and historians believe that Cézanne’s impact on modern art comes from his ability to reconcile the many contradictions in art. Instead of choosing visual reality over beauty, or vice versa, Cézanne broke down reality into basic forms, played with angles and depth perception, and used color to its full capacity to resolve the contradictions between chaotic visual perception and the beauty of God’s creation.

Cézanne's explorations inspired many cubist painters and others to experiment with ever more complex multiple views of the same subject, and, eventually, to the fracturing of form. Cézanne thus sparked one of the most revolutionary areas of artistic inquiry of the twentieth century, one which was to affect profoundly the development of modern art.

Notes

- ↑ The scheme presented here is essentially that of the Encyclopedia Britannica. Some alternative names are mentioned. On the whole the various classifications tend to converge.

- ↑ Some prefer to call it "the Romantic Period," but Cézanne was not primarily interested in Romanticism. The term here refers to personal disposition, rather than connection with a historical movement.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Marcel Brion, Cézanne (Thames and Hudson, 1974, ISBN 0500860041), 26.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brion, Marcel. Cézanne. Thames and Hudson, 1974. ISBN 0500860041

- Chu, Petra ten-Doesschate. Nineteenth-Century European Art. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2003. ISBN 0810935880

- Pissarro, Joachim. Pioneering Modern Painting, Cézanne & Pissarro 1865-1885. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. ISBN 0870701843

- Stokstad, Marilyn. Art History, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1995. ISBN 0130918687

- Sylvester, David. About Modern Art, 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001. ISBN 0300092024

External links

All links retrieved November 21, 2022.

- Cézanne at the WebMuseum

- Cézanne at Olga's Gallery

- The Bather in the MoMA Online Collection

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.