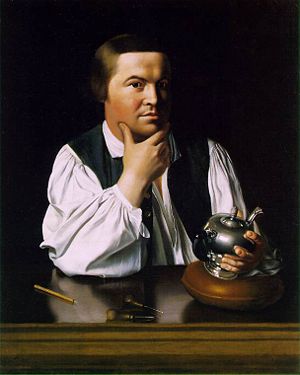

Paul Revere

Paul Revere (December 22, 1734 – May 10, 1818) was an American silversmith and a patriot in the American Revolution.

Because he was immortalized after his death for his role as a messenger in the battles of Lexington and Concord, Revere's name and his "midnight ride" are well-known in the United States as a patriotic symbol. In his lifetime, Revere was a prosperous and prominent Boston craftsman, who helped organize an intelligence and alarm system to keep watch on the British military.

Revere later served as an officer in one of the most disastrous campaigns of the American Revolutionary War, a role for which he was later exonerated. After the war, he returned to his silversmith trade and quickly recognized the potential for large-scale manufacturing of metal.

Early years

Revere was born probably in very late December, 1734, in Boston's North End. The son of a French Huguenot father and a Boston mother, Revere had numerous siblings with whom he was not particularly close. Revere's father, Apollos Rivoire, came to Boston at the age of 13, and was apprenticed to a silversmith. By the time he married Deborah Hichborn, a member of a long-standing Boston family that owned a small shipping wharf, Rivoire had anglicized his name to Paul Revere. Apollos (now Paul) passed his silver trade to his son Paul. Upon Apollos' death in 1754, Paul was too young by law to officially be the master of the family silver shop; Deborah probably assumed control of the business, while Paul and one of his younger brothers did the silver work. Revere fought briefly in the Seven Years War, serving as a second lieutenant in an artillery regiment that attempted to take the French fort at Crown Point, in present day New York. Upon leaving the army, Revere returned to Boston and assumed control of the silver shop in his own name. He was a silversmith, and also a prominent Freemason.[1]

Revere's silver work quickly gained attention in Boston; at the same time he was befriending numerous political agitators, including, most closely, Dr. Joseph Warren. During the 1760s Revere produced a number of political engravings and advertised as a dentist, and became increasingly involved in the actions of the Sons of Liberty. In 1770, he purchased, with his wife, Sarah Orne (who he had married in 1757 when she was twenty[2]), the house in North Square which is now open to the public. One of his most famous engravings was done in the wake of the Boston Massacre in March of 1770. It is not known whether Revere was present during the Massacre, though his detailed map of the bodies, meant to be used in the trial of the British soldiers held responsible, suggests that he had first-hand knowledge.[3] On May 3, 1773,[4] Sarah died, leaving behind six surviving children, and Revere married Rachel Walker, a much younger woman at just twenty-seven years of age,[5], with whom he would have five more surviving children.

After the Boston Tea Party in 1773, at which some reports place Revere, he began work as a messenger for the Boston Committee of Public Safety, often riding messages to New York and Philadelphia about the political unrest in the city. In 1774, Great Britain closed the port of Boston and began to quarter soldiers in great numbers all around Boston. At this time, Revere's silver business began to decline, and was largely in the hands of his son, Paul Revere, Jr. As 1775 began, talk of revolution was everywhere and Revere was more involved with the Sons of Liberty than ever.

The midnight ride of Paul Revere

The role for which he is most remembered today was as a night-time messenger before the battles of Lexington and Concord. His famous "Midnight Ride" occurred on the night of April 18–19, 1775, when he and William Dawes were instructed by Dr. Joseph Warren to ride from Boston to Lexington to warn John Hancock and Samuel Adams of the movements of the British army, which was beginning a march from Boston to Lexington, ostensibly to arrest Hancock and Adams, and seize the weapons stores in Concord.[6]

The British army (the King's "regulars"), which had been stationed in Boston since the ports were closed in the wake of the Boston Tea Party, was under constant surveillance by Revere and other patriots as word began to spread that they were planning a move. On the night of April 18, 1775, the army began its move across the Charles River toward Lexington, and the Sons of Liberty immediately went into action. At about 11 p.m., Revere was sent by Dr. Warren across the Charles River to Charlestown, on the opposite shore, where he could begin a ride to Lexington, while Dawes was sent the long way around, via the Boston Neck and the land route to Lexington. In the days before April 18, Revere had instructed Robert Newman, the sexton of the Old North Church, to send a signal by lantern to colonists in Charlestown as to the movements of the troops when the information became known; one lantern in the steeple would signal the army's choice of the land route, while two lanterns would signal the route "by sea" across the Charles River. This was done to get the message through to Charlestown in the event that both Revere and Dawes were captured. Newman and Captain John Pulling momentarily held two lanterns in the Old North Church as Revere himself set out on his ride, to indicate that the British soldiers were in fact crossing the Charles River that night.

Riding through present-day Somerville, Medford, and Arlington, Revere warned patriots along his route—many of whom set out on horseback to deliver warnings of their own. By the end of the night there were probably as many as 40 riders throughout Middlesex County carrying the news of the army's advancement. Revere certainly did not shout the famous phrase later attributed to him ("The British are coming!"), largely because the mission depended on secrecy and the countryside was filled with British army patrols; also, most colonial residents at the time considered themselves British, as they were all legally British subjects. Revere's warning, according to eyewitness accounts of the ride and Revere's own descriptions, was "the regulars are coming out." Revere arrived in Lexington around midnight, with Dawes arriving about a half hour later. Samuel Adams and John Hancock were spending the night at the Hancock-Clarke House in Lexington and, upon receiving the news, spent a great deal of time discussing plans of action. Revere and Dawes, meanwhile, decided to ride on toward Concord, where the militia's arsenal was hidden. They were joined by Samuel Prescott, a doctor who happened to be visiting Lexington.[7]

Revere, Dawes, and Prescott were detained by British troops in Lincoln at a roadblock on the way to nearby Concord. Prescott jumped his horse over a wall and escaped into the woods; Dawes also escaped, though soon after he fell off his horse and did not complete the ride. Revere was detained longer and had his horse confiscated, leaving Prescott the only rider to make it to Concord. Revere was escorted at gunpoint back toward Lexington. As morning broke and shots began to be heard, his British army guards became concerned and left Revere in the countryside, horseless. He walked back to Lexington and arrived in time to see the beginning of the battle on Lexington Green. The warning delivered by the three riders successfully allowed the militia to repel the British troops at Concord, who were then harried by guerrilla fire along the road back to Boston.

Revere's role was not particularly noted during his life. In 1861, over 40 years after his death, the ride became the subject of "Paul Revere's Ride," a poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. The poem has become one of the best known in American history and was memorized by generations of schoolchildren. Its famous opening lines are:

- Listen, my children, and you shall hear

- Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

- On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-Five;

- Hardly a man is now alive

- Who remembers that famous day and year

Today, parts of the ride are posted with signs marked "Revere's Ride." The full ride used Main Street in Charlestown, Broadway and Main Street in Somerville, Main Street and High Street in Medford, to Arlington center, and Massachusetts Avenue the rest of the way (an old alignment through Arlington Heights is called "Paul Revere Road").

Myths and legends of the midnight ride

In his poem, Longfellow took many liberties with the events of the evening, most especially giving sole credit to Revere for the collective achievements of the three riders (as well as the other riders whose names do not survive to history). Longfellow also depicts the lantern signal in the Old North Church as meant for Revere and not from him, as was actually the case. Other inaccuracies include claiming that Revere rode triumphantly into Concord instead of Lexington, and a general lengthening of the time frame of the night's events. For a long time, though, historians of the American Revolution as well as textbook writers relied almost entirely on Longfellow's poem as historical evidence—creating substantial misconceptions in the minds of the American people. In re-examining the episode, some historians in the twentieth century attempted to demythologize Paul Revere almost to the point of marginalization. While it is true that Revere was not the only rider that night, that does not destroy the fact that Revere was in fact riding. Other historians have since stressed his importance, however, including David Hackett Fischer in his book Paul Revere's Ride, an important scholarly study of Revere's role in the opening of the Revolution.

Popular myths and urban legends have persisted, though, concerning Revere's ride, mainly due to the tendency in the past to take Longfellow's poem as truth. Other riders, such as Israel Bissell and Sybil Ludington, are often suggested as having completed much more impressive rides than Revere's; however, the circumstances behind the others' rides were entirely different. Bissell was a news-carrier riding from Boston to Philadelphia with news of the battle at Lexington; Revere had made similar rides with the news in the years preceding the war. The only evidence for Ludington's ride is an oral tradition.

Longfellow's poem was never designed to be history and there are few serious historians today who would maintain that Revere was anything like the lone-wolf rider portrayed in the poem.

War years

At the beginning of the war, when Boston was occupied by the British army and most supporters of independence were evacuated, Revere and his family lived across the river in Watertown. In 1775, Revere was sent by the Massachusetts Provincial Congress to Philadelphia to study the working of the only powder mill in the colonies, and although he was allowed only to pass through the building, obtained sufficient information to enable him to set up a powder mill at Canton.

Upon returning to Boston in 1776, he was commissioned a Major of infantry in the Massachusetts militia in April of that year. In November, he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel of artillery, and was stationed at Castle William, defending Boston harbor, finally receiving command of this fort. He served in an expedition to Rhode Island in 1778, and in the following year participated in the disastrous Penobscot Expedition. After his return, he was accused of having disobeyed the orders of one of his commanding officers, and dismissed from the militia. Revere returned to his businesses at this time. He later obtained a formal court-martial, which exonerated him.[8]

Later years

After the war, finding the silver trade difficult in the ensuing depression, Revere opened a hardware and home goods store and later became interested in metal work beyond gold and silver. By 1788, he had opened an iron and brass foundry in Boston's North End. As a foundryman, he recognized a burgeoning market for church bells in the religious revival that followed the war, and became one of the best-known metal casters of that instrument, working with sons, Paul Jr. and Joseph Warren, in the firm Paul Revere & Sons. This firm cast the first bell made in Boston and produced over 900 in total. A substantial part of the foundry's business came from supplying shipyards with iron bolts and fittings for ship construction. Additionally, in 1801, Revere became a pioneer in the production in America of copper plating, opening North America's first copper mill, south of Boston in Canton. Copper from Revere's mill was used to cover the original wooden dome of the Massachusetts State House in 1802, and to produce sheeting for the hull of the USS Constitution.[9]

His business plans in the late 1780s were stymied by a shortage of adequate money in circulation. His plans rested on his entrepreneurial role as a manufacturer of cast iron, brass, and copper products. Alexander Hamilton's national policies regarding banks and industrialization exactly matched his dreams, and he became an ardent Federalist, committed to building a robust economy and a powerful nation. His copper and brass works eventually grew, through sale and corporate merger, into a large, national corporation, Revere Copper and Brass, Inc.

Rachel Walker Revere died on June 6, 1813, after suffering a prolonged illness.[10] Paul Revere died on May 10, 1818,[11] at the age of 83, at his home on Charter Street in Boston. He is buried in the Old Granary Burying Ground on Tremont Street.

Legacy

After his death, Revere was praised for characteristics of good health, prosperity, honesty, and charity. His legend did not die with him, but instead he was forever immortalized as an American hero defined by a ride that truly characterized only a brief moment in his long and vibrant life.[12]

Paul Revere appears on the $5,000 Series EE Savings Bond issued by the United States Government. The copper works he founded in 1801 continues as Revere Copper Products, Inc. with manufacturing divisions in Rome, New York, and New Bedford, Massachusetts.

His original silverware, engravings, and other works are highly regarded today and can be found on display at prominent museums, such as the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Today, noted silversmiths such as Reed & Barton offer reproduction "Paul Revere Bowls" for sale to the public.

Schools named for Paul Revere

- Paul Revere Middle School, Los Angeles, California.[13]

- Paul Revere School, Revere, Massachusetts.[14]

- Paul Revere Middle School, Houston, Texas.[15]

- Paul Revere Elementary School, Chicago, Illinois.[16]

- Paul Revere School, Cleveland, Ohio.[17]

- Paul Revere Elementary School, San Francisco, California.[18]

- Paul Revere Primary School, Blue Island, Illinois.[19]

Notes

- ↑ Decoding the Past: Mysteries of the Freemasons—America, video documentary, written by Noah Nicholas and Molly Bedell (June 2006; New York: A&E Home Video, August 2006).

- ↑ Forbes, 58.

- ↑ Forbes, 159-60.

- ↑ Forbes, 183.

- ↑ Forbes, 185.

- ↑ Forbes, 246.

- ↑ Forbes, 257-263.

- ↑ Forbes, 353-360.

- ↑ Forbes, 425-426.

- ↑ Forbes, 450.

- ↑ Forbes, 462.

- ↑ Forbes, 463-464.

- ↑ Los Angeles Unified School District, Paul Revere Middle School, Paul Revere Middle School Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- ↑ Revere Public Schools, Paul Revere School, Paul Revere School Website Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- ↑ Houston Independent School District, Welcome to Paul Revere Middle School, Revere Middle School Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- ↑ Chicago Public Schools, Paul Revere Elementary School, Paul Revere Elementary Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- ↑ Paul Revere, Paul Revere Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- ↑ San Francisco Unified School District, Paul Revere ES, Paul Revere ES Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- ↑ Cook County School District, Paul Revere Primary School, Paul Revere Primary School. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chicago Public Schools. Paul Revere Elementary Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- Cook County School District. Paul Revere Primary School. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- Decoding the Past: Mysteries of the Freemasons—America, video documentary, written by Noah Nicholas and Molly Bedell (June 2006; New York: A&E Home Video, August 2006).

- Fischer, David Hackett. Paul Revere's Ride. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994. ISBN 9780195088472

- Forbes, Esther. Paul Revere and the World He Lived In. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1942.

- Houston Independent School District. Revere Middle School Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- Los Angeles Unified School District. Paul Revere Middle School. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- Massachusetts Historical Society. Paul Revere's Three Accounts of His Famous Ride. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1961.

- Paul Revere Memorial Association. Paul Revere, Artisan, Businessman and Patriot—The Man Behind the Myth. Boston: Paul Revere Memorial Association, 1988.

- Revere Public Schools. Paul Revere School Website Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- San Francisco Unified School District. Paul Revere ES. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- Steblecki, Edith J. Paul Revere and Freemasonry. Boston: Paul Revere Memorial Association, 1985.

- Triber, Jayne E. A True Republican: The Life of Paul Revere. Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 1998. ISBN 9781558491397

External links

All links retrieved November 22, 2022.

- Librivox recording of Paul Revere's Ride by Longfellow

- The Paul Revere House

- Paul Revere Heritage Project

- Dr. Samuel Prescott Completed Paul Revere's Ride

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.