The Pharisees were a religious and political movement of ancient Israel and the precursors of Rabbinic Judaism. They emerged in opposition to the corruption of the Hasmonean dynasty and its allies, the Sadducees, in the second century B.C.E. They were characterized by an emphasis on popular piety rather than priestly elitism, a tradition of Oral Law in addition to the written Torah, and an affirmation of the doctrine of the resurrection of the dead in the coming messianic age as taught by the prophets—all of which the Sadducees tended to reject.

During the early years of the Common Era, a major internal debate existed between the followers of the two Pharisaic sages, Hillel and Shammai, representing a flexible versus a strict approach to the Jewish law, respectively. After the Jewish Revolt against Rome resulted in the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem in 70 C.E., the followers of Hillel prevailed. The Pharisaic movement went on to create the foundations for what is now known as Rabbinic Judaism, through its deliberations at Yavneh (Jamnia) in the second century C.E., and the later compiling of the Mishnah and teh Talmud.

Christian portraits of the Pharisees in the New Testament tend to portray them as narrow-minded hypocrites and the mortal opponents of Jesus. However, recent scholarship has shown that some Pharisees were supporters of Jesus and the early Christian movement, and some scholars see a direct influence of Pharisees such as Hillel on the teachings of Jesus. Deeper study of the nature and history of the Pharisees can help foster Jewish-Christian dialog in an atmosphere of mutual respect and understanding.

Background

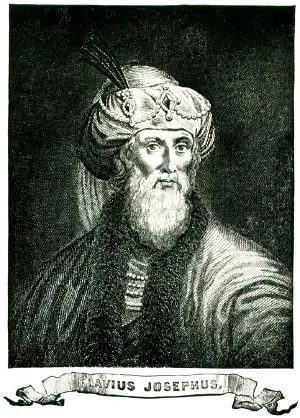

For the background of the Pharisees, historians are largely dependent on the accounts of Josephus, the Jewish historian of the late first century C.E. who was himself a member of the Pharisees but later collaborated with the Romans during the Jewish Revolt of 66-70 C.E.

The word Pharisees comes from the Hebrew ( פרושים) prushim from (פרוש) parush, meaning "separated"—referring to one who is separated for a life of purity. According to Josephus' accounts, the Pharisees emerged in opposition to the corruption of the Hasmonean dynasty of the second century B.C.E. The Hamoneans had assumed power in the wake of the successful revolt against the Seleucid Greeks. Led by Judah Maccabee, the Jews had liberated Jerusalem from Greek rule in 165 B.C.E. and restored its Temple, which had been defiled under the Antiochus IV. Judah's nephew, John Hyrcanus, established the Hasmonean dynasty, in which the priests held direct political power as well as religious authority. Although the Hasmoneans were heroes for resisting the Seleucids, their reign lacked the legitimacy conferred by the descent from the Davidic dynasty of the First Temple Era. The hope of a Messiah, son of David, developed during this period in tension with the reality of Hasmonean rule.

Around this time the Sadducees emerged as the party of the priests and allied Hasmonean elites, taking their name, Sadducee, from King Solomon's loyal priest Zadok. The Pharisees emerged out of the group of scribes and sages who objected to the Hasmonean monopoly on power, hoped for a Davidic Messiah, and criticized the growing corruption of the Hasmonean court.

During the Hasmonean period, the Sadducees and Pharisees functioned primarily as political parties. According to Josephus, the Pharisees opposed the Hasmonean war against the Samaritans and the forced conversion of the Idumeans. The political rift between the two parties grew wider under the Hasmonean king Alexander Jannaeus, who adopted Sadduceean rites in the Temple. There was a brief civil war that ended with a bloody repression of the Pharisees.

Alexander was succeeded by his widow, Salome Alexandra, who was more favorably inclined toward the Pharisees. Alexandra installed as high priest her eldest son, the pro-Pharisee Hyrcanus II, and the Sanhedrin, or ruling council, was reorganized along lines that strengthened Pharisaic influence.

Upon Alexandra's death, Hyrcanus II gained the Pharisees' support, while her younger son, Aristobulus, found support among the Sadducees. The conflict between Hyrcanus and Aristobulus culminated in another civil war that ended when the Roman general Pompey captured Jerusalem in 63 B.C.E. and inaugurated the Roman period of Jewish history. Echoing the prophet Jeremiah's attitude toward the Babylonian capture of Jerusalem in 586 B.C.E., the Pharisees regarded Pompey’s defilement of the Temple in Jerusalem as a divine punishment for the Sadducean abuse of the priesthood. They asked Pompey to abolish the royalty of the Hasmoneans ("Ant." xiv. 3, § 2). Pompey named Hyrcanus II high priest and "ethnarch," a lesser title than "king." In 57 B.C.E. Hyrcanus was deprived of the remainder of his political authority, and ultimate jurisdiction was given to the Roman Proconsul of Syria.

The Proconsul Cabineus established five regional synhedria (Sanhedrins, or councils) to regulate the internal affairs of the Jews, while the Great Sanhedrin in Jerusalem interpreted Jewish law and adjudicated appeals. Its legislative powers varied, however, depending on Roman policy.

In matters of state finance, administration, and military affairs, the Proconsul ruled through Hyrcanus's Idumaean associate Antipater.[1] Later, Antipater's sons governed the northern and southern districts of the former territory of Israel: Phasael administering Judea, and Herod ruling Galilee. In 40 B.C.E., however, Aristobulus's son Antigonus overthrew Hyrcanus II and named himself both king and high priest, placing the Pharisees once again at a disadvantage.

Herod fled to Rome, where he sought the support of Mark Antony and Octavian, and secured recognition by the Roman Senate. He soon dislodged Antigonus and was installed as king, thus bringing an end to the Hasmonean dynasty. Sadducean opposition to Herod led him to treat the Pharisees favorably at first. His Idumean background and his close association with Rome, however, made him an unpopular ruler. Herod's massive restoration and expansion of the Temple of Jerusalem may have been designed to gain popular support, but his notorious treatment of his family and his ruthless suppression of the Hasmonaeans further eroded his popularity. His willingness to adorn the new Temple with a gold Roman eagle was a particularly unpopular stance, which alienated the Pharisees, for whom resistance to Hellenization was a hallmark.

Herod's paranoia toward any perceived threat to his throne also proved incompatible with the Pharisees' hope in the coming Davidic Messiah. In 6 B.C.E., Herod executed several Pharisaic leaders who had announced that the birth of the Messiah would mean the end of Herod's rule. Then, in 4 B.C.E., when young Pharisaic Torah-students smashed the golden Roman eagle over the main entrance of Herod's Temple, he had 40 of them, along with two of their professors, burned alive. ("Ant." xvii. 2, § 4; 6, §§ 2-4). Meanwhile, Herod found willing allies among the Sadducees, who now re-emerged to reclaim the high priesthood and challenge Pharisaic pre-eminence.

From this point onward, Josephus' accounts are joined by other sources, including various Talmudic references and early Christian writings such as the letters of Saint Paul (himself a former Pharisee), the Gospels, and the Book of Acts.

Theological characteristics

The Pharisaic approach to Judaism was characterized by several distinctive attitudes:

First, Pharisees were a movement of popular piety, rather than priestly elitism. They interpreted Exodus 19:4-5 literally: "If you will obey my voice and keep my covenant, you shall be my own possession among all peoples; for all the earth is mine, and you shall be to me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation." Moreover, in the Pharisees' view, the Torah already provided the way for every Jew to lead a priestly life. The Pharisees believed that all Jews in their ordinary lives should observe the rules and rituals concerning purification and all 613 of the commandments which the Pharisees discerned in the Law of Moses.

Second, the Pharisees believed in an Oral Law as well as a Written Law. In addition to the Torah recognized by the Sadducees, the Pharisees held that God had also revealed to Moses an Oral Torah that functioned to elaborate and explicate what was written. Therefore, the Law did not end with what was written in the Torah scrolls, but was also revealed orally by Moses and his successors into the present age. It was the function of the prophets and sages to explicate the Oral Torah and clarify its application in contemporary cirumstances.

Third, the Pharisees believed in the resurrection of the dead in a future age, which would be ushered in by the Messiah, in whom they earnestly hoped.

Fourth, the Pharisees placed a greater emphasis on the scriptural authority of the prophets and other biblical writings than did the Sadducees. (During this period, no authorized list of scriptures outside of the Torah yet existed.)

Finally, the Pharisees resisted Hellenization, viewing the Sadducees as generally corrupted by their association with Hasmonean and Roman rulers.

Hillel vs. Shammai

Two great Pharisaic teachers emerged during early Common Era: Hillel and Shammai. Their two schools of Pharisaism would shape an internal debate within the movement that had a crucial impact on Jewish history.

Shammai was the stricter of the two sages, insisting on a narrow interpretation of the Torah on most issues, while Hillel was the more liberal. A famous story characterizing them tells of a time when a Gentile man came first to Shammai and asked to be converted to Judaism, upon the condition that Shammai summarize the entire Torah while standing on one leg. Shammai took offense at the request, and he drove the applicant away with a measuring stick. Hillel, on the other hand, did as the seeker requested, standing on one leg and declaring: "What is hateful to you, do not unto your neighbor. This is the Law on the Prophets; the rest is commentary. Now, go and study." (Shabbat, 31a).

Each of the two teachers—Hillel being the elder—served in turn as the leading figure of the Sanhedrin, and debates raged far and wide among their disciples. In the years following their death, these disputations increased to such an extent as to give rise to the saying: "The one Law has become two laws" (Tosef., Hag. 2:9; Sanh. 88b; Sotah 47b).

The Shammaites were said to have inherited the stern and unbending character of their founder. They were also intensely patriotic, refusing to submit to foreign rule, and they opposed all friendly relations with the Romans. The House of Shammai particularly abhorred the Roman tax system, as well as the Jewish collaborators who served as tax collectors. Under the leadership of Zealot Judas the Galilean and a Shammaite named Zadok (Tosef., Eduy. ii. 2; Yeb. 15b), a popular political movement arose to oppose, even violently, Roman laws.

The Hillelites, animated by a more tolerant and peaceful spirit, consequently lost influence. Feelings between the two schools grew so hostile that they even refused to worship together. As the struggle intensified, the Shammaites attempted to prevent all communication between Jews and Gentiles, prohibiting Jews even from buying food from their Gentile neighbors. The Hillelites opposed such extreme exclusiveness. However, in the Sanhedrin, the Shammaites, together with the Zealots, carried the day.

The destruction of the Temple

By 66 C.E. Jewish discontent with Rome had escalated beyond the point of no return, and the Jewish Revolt broke out in full force. The Romans did not succeed in controlling Jerusalem until 70 C.E. when they destroyed the Temple of Jerusalem and broke the back of the revolt, although pockets of resistance remained. The event was a profoundly traumatic experience for the Jews that marked the end of an era. Ironically, however, it would place the Pharisees in a position of unrivaled leadership, since the priesthood and its affiliated Sadducean party was left without a base, and the Zealots had been discredited by the catastrophic outcome of the revolt.

The House of Shammai and the House of Hillel continued their disputes even after the demise of the Temple, probably until the reorganization of the Sanhedrin under the presidency of Gamaliel II around 80 C.E. By that time, all hope for victory over Rome had been lost for the time being, and the House of Shammai was obliged to take a subservient role. Formerly disputed legal points were brought up for review, and in nearly every case the opinion of the Hillelites prevailed (Tosef., Yeb. i. 13; Yer. Ber. i. 3b). Henceforth, the House of Hillel would be the leading voice of Pharisaism, and Pharisaism would be the leading voice of Judaism.

From Pharisees to rabbis

Following the destruction of the Temple, Rome governed Judea through a Roman Procurator at Caesarea and a Jewish Patriarch. Yohanan ben Zakkai, a leading Pharisee, was appointed the first Patriarch (his Hebrew tile was Nasi, which means both "prince" and "president). He reestablished the Sanhedrin at Yavneh (Jamnia) under Pharisaic control. With the Temple no longer operating, the rabbis instructed Jews to support their synagogues and give money to charities in lieu of offering tithes to the priests and making costly sacrifices at the Temple. Study and prayer in local synagogues replaced tithing and Temple pilgrimages as important religious duties.

The Pharisees' hope in the coming of a Messianic king, however, had not been extinguished. When the Emperor Hadrian threatened to rebuild Jerusalem as a pagan city dedicated to Jupiter, in 132 C.E., some of the leading sages of the Sanhedrin supported a major rebellion led by Simon Bar Kochba. Rabbi Akiva, one of the greatest sages of his day, went so far as to declare Bar Kochba to be the long-awaited Messiah.

Bar Kochba succeeded in establishing a short-lived independent Jewish state that was conquered by the Romans in 135 C.E. The Romans executed ten leading members of the Sanhedrin, including Akiva, and the slaughter of the Jewish population reached more than 100,000 souls.

In the aftermath of the revolt, the Romans forbade Jews to even enter Jerusalem, let alone promote the rebuilding of the Temple. The Romans eventually reconstituted the Sanhedrin under the leadership of Judah ha-Nasi and declared the position of "Nasi" to be hereditary.

Around 200 C.E. Judah ha-Nasi is traditionally thought to have edited the collection of rabbinical opinions and rulings known as the Mishnah. These often divergent religious views, championed by Pharisaic sages known as the Tannaim between 70-200 C.E., are considered the first work of Rabbinic Judaism. The Mishnah also serves as the foundation for the vast later compendium of Jewish thought known as the Talmud. The inclusion by Judah ha-Nasi of often opposing rabbinical opinions in the Misnah led to a Jewish attitude of theological inclusiveness, accepting a wide range of opinion on nearly every issue of Jewish theology.

The Pharisaic attitude of emphasizing learning and personal piety over Temple ritual had thus come to dominate Judaism nearly completely. One exception were the Karaites, Jews who rejected the concept of the Oral Torah and thus refused to accept the authority of rabbinical interpretations or additions to the Law of Moses. Some Karaite communities still exist in parts of Asia Minor and Eastern Europe.

"Pharisees" and Christianity

The New Testament often portrays the Pharisees in the role of Jesus' opponents. They emerge as self-righteous rule-followers, hypocrites, and religious conservatives who conspire to do away with Jesus. Indeed, the word "pharisee" has come into semi-common usage in English to describe a hypocritical and arrogant person who places the letter of the law above its spirit.

However, a close examination of the Gospels reveals that it was actually the Sadducean high priest and his family who had Jesus arrested and turned him over to the Romans on a charge of treason against Rome (John 18). No Pharisee is named as a persecutor of Jesus, while several Sadducees are named as such; and one Pharisee, Nicodemus, is depicted as courageously defending Jesus before the Sanhedrin (John 7:50-51). Later, in the Book of Acts, another Pharisee, Gamaliel I, known to Jewish history as the grandson of Hillel, successfully defended the disciples before the Sanhedrin against Sadducean persecution (Acts 5:33-40). Acts also mentions that some of the members of the Jerusalem church were Pharisees themselves (Acts 15:5) and that thousands of early Christians were "zealous for the Law." (Acts 21:21) Later, when Saint Paul found himself on trial before the Sanhedrin, (Acts 23) he identified himself as a Pharisee who believed in the resurrection, which Sadducees denied, and thus won a temporary reprieve from the accusations of the Sadducean high priest.

Some scholars have argued that Jesus was himself a Pharisee, and that his arguments with Pharisees is a sign of inclusion, since disputation is the dominant narrative mode in the Talmud. According to this theory, the portrait of the Pharisees in the New Testament is an anachronistic caricature, arising from the attitude of the church at the time the Gospels were written, when Christians no longer considered themselves to be part of the Jewish community.

Another way of looking at the portrayal of the Pharisees in the New Testament is that it represents the strict attitude of the House of Shammai rather than that of Hillel. For example, Jesus' willingness to associate with tax collectors might have been offensive to the followers of Shammai, but probably not to the disciples of Hillel. Similarly, when Jesus indicated that one should "render unto Caesar" the taxes due to him (Mt. 22), he adopted an attitude acceptable to the followers of Hillel, but opposed by the House of Shammai in the period leading up to the Jewish Revolt.

Like Hillel, Jesus took a flexible stand on many issues in the Torah—such as healing on the Sabbath and association with Gentiles and sinners—while holding firm to basics such as "love the Lord God with all thy heart" (Deuteronomy 6:5) and "Love thy neighbor as thyself." (Leviticus 19:18) Some suggest that Jesus may even have been a hearer of Hillel when he spoke with the teachers in the Temple as a 12-year-old.

Nevertheless, the portrait of the Pharisees as Jesus' mortal opponents is etched deeply into Christian culture and remains a divisive factor in Jewish-Christian dialog even today.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boccaccini, Gabriele. Roots of Rabbinic Judaism. William B. Eerdmans Pub., 2001. ISBN 0802843611

- Bowker, John. Jesus and the Pharisees. Cambridge University Press, 1973. ISBN 9780521200554

- Cohen, Shaye J. D. From the Maccabees to the Mishnah. Westminster John Knox Press, 1988. ISBN 0664250173

- Fredriksen, Paula. From Jesus to Christ. Yale University Press, 1990. ISBN 0300048645

- Neusner, Jacob, and Bruce Chilton. In Quest of the Historical Pharisees. Baylor University Press, 2007. ISBN 1932792724

- Neusner, Jacob. Torah From our Sages: Pirke Avot. Rossel Books; 1st edition, 1983. ISBN 0940646056

- ___________. Judaism in the Beginning of Christianity. Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 2000. ISBN 9780800617509

- Schwarz, Leo, ed. Great Ages and Ideas of the Jewish People. (original 1956) Modern Library, (Random House) 1977. ISBN 039460413X

External links

All links retrieved November 23, 2022.

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Pharisees. jewishencyclopedia.com.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.