Poland

| Rzeczpospolita Polska Republic of Poland |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: Mazurek Dąbrowskiego (Dąbrowski's Mazurka) |

||||||

| Location of Poland (dark green) – on the European continent (green dark grey) – in the European Union (green) |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Warsaw 52°13′N 21°02′E | |||||

| Official languages | Polish | |||||

| Recognized regional languages | German, Belarusian, Lithuanian, Kashubian | |||||

| Ethnic groups (2011) | 97% Polish, 6% other and unspecified [1] | |||||

| Demonym | Pole/Polish | |||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic | |||||

| - | President | Andrzej Duda | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Donald Tusk | ||||

| Formation | ||||||

| - | Christianization1 | April 14, 966 | ||||

| - | First Republic | July 1, 1569 | ||||

| - | Second Republic | November 11, 1918 | ||||

| - | People's Republic | December 31, 1944 | ||||

| - | Third Republic of Poland | January 30, 1990 | ||||

| EU accession | 1 May 2004 | |||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 312,685 km² 2(69th) 120,696.41 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 3.07 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2022 census | |||||

| - | Density | 122/km² (75th) 315.9/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | |||||

| - | Per capita | |||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | |||||

| - | Per capita | |||||

| Gini (2022) | 26.3[4] | |||||

| Currency | Złoty (PLN) |

|||||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .pl | |||||

| Calling code | [[+48]] | |||||

| 1 | The adoption of Christianity in Poland is seen by many Poles, regardless of their religious affiliation or lack thereof, as one of the most significant national historical events; the new religion was used to unify the tribes in the region. | |||||

| 2 | The area of Poland according to the administrative division, as given by the Central Statistical Office, is 312,679 km² (120,726 sq mi) of which 311,888 km² (120,421 sq mi) is land area and 791 km² (305 sq mi) is internal water surface area. | |||||

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe on the boundary between Eastern and Western European continental masses, and is considered at times a part of Eastern Europe.

The first Polish state was baptized in 966, an event that coincided with the baptism of Duke Mieszko I. Poland became a kingdom in 1025, and in 1569 it cemented a long association with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania by uniting to form the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Commonwealth collapsed in 1795, and at that time Poland ceased to exist as an independent state.

Poland regained its independence in 1918 after World War I but lost it again in World War II, occupied by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, emerging several years later as a communist country within the Eastern Bloc under the control of the Soviet Union. In 1989, communist rule was overthrown and Poland became what is informally known as the "Third Polish Republic."

Of all the countries involved in World War II, Poland lost the highest percentage of its citizens: over six million perished, half of them Polish Jews. The main German Nazi death camps were in Poland. Of a pre-war population of 3,300,000 Jews, 3,000,000 were killed during the Holocaust. Poland made the fourth-largest troop contribution to the Allied war effort, after the Soviets, the British and the Americans.

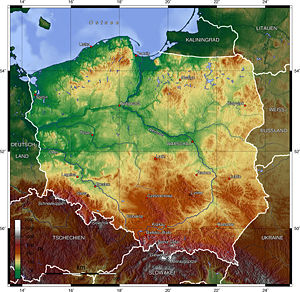

Geography

Poland is bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south, Ukraine and Belarus to the east, and the Baltic Sea, Lithuania and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north. The country's total area is 120,728 square miles (312,679 square kilometers) making it the 69th largest country in the world and seventh largest in Europe. It is slightly smaller than New Mexico in the United States.

The geological structure of Poland has been shaped by the continental collision of Europe and Africa over the past 60 million years, on the one hand, and the Quaternary glaciations of northern Europe, on the other. Both processes shaped the Sudetes and the Carpathians. The moraine landscape of northern Poland contains soils made up mostly of sand or loam, while the ice-age river valleys of the south often contain loess. The Cracow-Częstochowa Upland, the Pieniny, and the Western Tatras consist of limestone, while the High Tatras, the Beskids, and the Karkonosze are made up mainly of granite and basalts. The Kraków-Częstochowa Upland is one of the oldest mountain ranges on earth.

Poland’s territory extends across five geographical regions. In the northwest is the Baltic seacoast, marked by several spits, coastal lakes (former bays that have been cut off from the sea), and dunes. The center and parts of the north lie within the Northern European Lowlands. Rising gently above these lowlands is a geographical region comprising the four hilly districts of moraines and moraine-dammed lakes formed during and after the Pleistocene ice age.

The Masurian Lake District is the largest of the four and covers much of northeastern Poland. The lake districts form part of the Baltic Ridge, a series of moraine belts along the southern shore of the Baltic Sea. South of the Northern European Lowlands lie the regions of Silesia and Masovia, which are marked by broad ice-age river valleys. Farther south lies the Polish mountain region, including the Sudetes, the Cracow-Częstochowa Upland, the Świętokrzyskie Mountains, and the Carpathian Mountains, including the Beskids. The highest part of the Carpathians is the Tatra Mountains, along Poland’s southern border.

Poland has 21 mountains over 6561 feet (2000 meters) in elevation, all in the High Tatras. In the High Tatras lies Poland’s highest point, the northwestern peak of Rysy, at 8198 feet(2499 meters) in elevation. At its foot lies the mountain lake, the Morskie Oko. Among the most beautiful mountains of Poland are the Bieszczady Mountains in the far southeast of Poland, whose highest point in Poland is Tarnica, with an elevation of 4416 feet (1346 meters). Tourists also frequent the Gorce Mountains in Gorce National Park. The lowest point in Poland-—at (seven feet (two meters) below sea level-—is at Raczki Elbląskie, near Elbląg in the Vistula Delta.

The climate is oceanic in the north and west and becomes gradually warmer and continental as one moves south and east. Summers are generally warm, with average temperatures between 68°F (20°C) and 80.6°F (27°C. Winters are cold, with average temperatures around 37.4°F (3°C) in the northwest and 17.6°F (–8°C) in the northeast. Precipitation falls throughout the year, although, especially in the east; winter is drier than summer. The warmest region in Poland is located in the south, where temperatures in the summer average between 73.4°F (23°C) and (86°F (30°C). The coldest region is in the northeast in the Podlachian Voivodeship near the border of Belarus. Cold fronts which come from Scandinavia and Siberia bring temperatures in the winter in Podlachian ranging from 5°F (-15°C) to 24.8°F (-4°C).

The longest rivers are the Vistula, 678 miles (1047km) long, the Oder—which forms part of Poland’s western border—531 miles (854km) long, its tributary, the Warta, 502 miles (808km) long, and the Bug—a tributary of the Vistula—480 miles (772km) long. The Vistula and the Oder flow into the Baltic Sea, as do numerous smaller rivers in Pomerania. The Łyna and the Angrapa flow by way of the Pregolya to the Baltic Sea, and the Czarna Hańcza flows into the Baltic through the Neman.

Poland’s rivers have been used since early times for navigation. The Vikings, for example, traveled up the Vistula and the Oder in their longships. In the Middle Ages and in early modern times, when Poland-Lithuania was the breadbasket of Europe, the shipment of grain and other agricultural products down the Vistula toward Gdańsk and onward to western Europe took on great importance.

With almost ten thousand closed bodies of water covering more than one hectare (2.47 acres) each, Poland has one of the highest numbers of lakes in the world. The largest lakes, covering more than 38.6 square miles (100 square kilometers), are Lake Śniardwy and Lake Mamry in Masuria, as well as Lake Łebsko and Lake Drawsko in Pomerania.

Among the first lakes whose shores were settled are those in the Greater Polish Lake District. The stilt house settlement of Biskupin, occupied by more than 1000 residents, was founded before the seventh century B.C.E. by people of the Lusatian culture. The ancestors of today’s Poles, the Polanie, built their first fortresses on islands in these lakes. The legendary Prince Popiel is supposed to have ruled from Kruszwica on Lake Gopło. The first historically documented ruler of Poland, Duke Mieszko I (c. 935 – May 25, 992), had his palace on an island in the Warta River in Poznań.

Błędów Desert is a desert located in Southern Poland in the Lesser Poland region it also stretches over the Zagłębie Dąbrowskie region. It has a total area of 12.3 square miles (32km²). The only desert located in Poland, and one of five natural deserts in Europe, it was created thousands of years ago by a melting glacier. The specific geological structure has been of big importance - the average thickness of the sand layer is about 40 meters (maximum 70 meters), which made the fast and deep drainage very easy. The desert began to shrink in the late twentieth century. The phenomenon of mirages has been known to exist there.

More than one percent of Poland’s area—1214 square miles (3145 square kilometers)—is protected within 23 National Parks. In this respect, Poland ranks first in Europe. Forests cover 28 of Poland’s land area. More than half of the land is devoted to agriculture. While the total area under cultivation is declining, the remaining farmland is more intensively cultivated.

Many animals that have since died out in other parts of Europe survive in Poland, such as the wisent (Bison bonasusin) the ancient woodland of the Białowieża Forest and in Podlachia. Other such species include the brown bear in Białowieża, in the Tatras, and in the Beskids, the gray wolf and the Eurasian lynx in various forests, the moose in northern Poland, and the beaver in Masuria, Pomerania, and Podlachia. In the forests one also encounters game animals, such as red and roe deer and boars. In eastern Poland there are a number of ancient woodlands, like Białowieża, that have never been cleared. There are also large forested areas in the mountains, Masuria, Pomerania, and Lower Silesia.

Poland is the most important breeding ground for European migratory birds. Out of all of the migratory birds who come to Europe for the summer, one quarter breed in Poland, particularly in the lake districts and the wetlands along the Biebrza, the Narew, and the Warta, which are part of nature reserves or national parks. In Masuria, there are villages in which storks outnumber people.

Flooding is a natural hazard. Environmental issues relate to air pollution, which remained serious in 2007 because of sulfur dioxide emissions from coal-fired power plants, and the resulting acid rain which damages forest. Water pollution from industrial and municipal sources is also a problem, as is disposal of hazardous wastes. Pollution levels were expected to decrease as industrial establishments bring their facilities up to the European Union code, but at substantial cost to business and the government.

Warsaw is the capital of Poland and is its largest city. Located on the Vistula River between the Baltic Sea coast and the Carpathian Mountains, its population in 2006 was estimated at 1,700,536, with a metropolitan area of approximately 2,600,000. The largest metropolitan areas in Poland are the Upper Silesian Coal Basin centered on Katowice (3.5 million inhabitants), Łódź (1.3 million), Kraków (1.3 million), the “Tricity” of Gdańsk-Sopot-Gdynia in the Vistula delta (1.1 million), Poznań (0.9 million), Wrocław (0.9 million), and Szczecin (0.9 million).

History

Prehistory

The Stone Age era in Poland lasted 500,000 years, and cultures ranged from early human groups with primitive tools to advanced agricultural societies using sophisticated stone tools, building fortified settlements and developing copper metallurgy.

Early Bronze Age cultures there begin around 2400/2300 B.C.E. The Iron Age started around 750/700 B.C.E. The most famous archaeological finding is the Biskupin fortified settlement on the lake, of the Lusatian culture of the early Iron Age. Biskupin is the location of a life-size model of an Iron Age fortified settlement (gród) in Poland.

Celtic, Germanic and Baltic tribes

Peoples belonging to numerous archaeological cultures identified with Celtic, Germanic and Baltic tribes lived in various parts of Poland from about 400 B.C.E. Other groups were no doubt also present. Short of using written language, many of them developed advanced material culture and social organization. Characteristic of the period was relatively high geographical mobility of large groups of people, even equivalents of today's nations. The Germanic people lived in today's Poland for several centuries, while many of their tribes also migrated out in the southern and eastern directions.

Roman Empire

With the expansion of the Roman Empire came also the first written remarks by Roman authors on Polish lands. As the Roman Empire was nearing its collapse and the nomadic peoples invading from the east destroyed, damaged or destabilized the various Germanic cultures and societies, the Germanic people left eastern and central Europe for the safer and wealthier southern and western parts of the continent.

Slavic tribal society

Whether Slavic tribes were indigenous to the lands that were to become Poland or migrated there from elsewhere is in dispute. The Slavs were "known to other people" as those tribes located between the Vistula and Dnepr until the middle of the first century B.C.E. After that they expanded to the Elbe (Labe) River and Adriatic Sea and down the Danube. Slavic people were markedly less developed than Germanic people of the time, which can be seen from the comparable quality of the pottery and other artifacts left by the two groups. They lived from cultivation of crops and were farmers, who engaged in hunting and gathering. A westward movement of Slavic people was facilitated in part by the previous withdrawal of Germanic people and their own migration toward the safer and more attractive areas of western and southern Europe, away from marauding Huns, Avars, and Magyars.

Tribes built many gords - fortified structures with primitive walls enclosing a group of wooden houses, built either in rows or in circles, from the seventh century on. A number of such Polish tribes formed small states from the eighth century, some of which coalesced later into larger ones. Among those were the Vistulans (Wiślanie) in southern Poland, with Kraków and Wiślica as their main centers, and later the eastern and western Polans (Polanie, lit. "people of the fields), who settled in the flatlands around Giecz, Poznań and Gniezno that eventually became the foundation and early center of Poland.

Christian kingdom

A number of tribes united, about 840 C.E., under a legendary king known as Piast. Poland's first historically documented ruler, Mieszko I (935-992), reputedly a descendant of Piast, was baptized in 966, adopting Catholic Christianity as the nation's new official religion, to which the bulk of the population converted over the next centuries. Lands under Duke Mieszko's rule encompassed Greater Poland, Lesser Poland, Masovia, Silesia and Pomerania, and totaled about 96,525 square miles (250,000km²) in area, with a population of about one million.

Mieszko's son and successor Boleslaw I (992-1025), known as the Brave, married a Czech princess Dobrawa, and several other wives. He further established the Christian Church, and conducted successful wars against Holy Roman Emperor Henry II, expanding the Polish domain beyond the Carpathian Mountains and the Oder (Odra) and Dnestr rivers. The pope crowned him king by in 1025.

Poland then sustained years of internal disorder and invasions. Mieszko II, who was crowned in 1025, faced a rebellion by landlords, conflict with his brothers, and invasion by the troops of Holy Roman Emperor Conrad II. Casimir I of Poland (1037-1058) unified the country, Boleslav II of Poland made himself king in 1076, but had to abdicate in 1079. There was a conspiracy that involved Boleslav's brother Wladyslaw Herman (1040-1102) and the Bishop of Krakow. Boleslaw had Bishop of Krakow Stanislaw tortured and executed. However, Boleslaw was forced to abdicate the Polish throne because of pressure from the Catholic Church and nobility. Władysław I Herman took over the throne and also had to abdicate in 1102, giving the power to his sons Zbigniew of Poland and Bolesłav III Wrymouth who reigned simultaneously, until Boleslav had his half-brother banished from the country in 1107, blinded in 1112, then executed.

Fragmentation

After Bolesłav III died in 1138, the kingdom was divided among four of his sons, ushering in a period of fragmentation. For two centuries, the Piasts sparred with each other, the clergy, and the nobility, for control over the divided kingdom. Poland of the thirteenth century, was no longer one solid political entity. By the "grace of God" the princes were absolute lords of their dominions. Church grew constantly stronger on account of its splendid organization, its accumulation of wealth and the moral control it exercised over the people. The sovereignty of the former state became diffused among a number of smaller independent principalities, with only the common bonds of language, race, religion and tradition.

German settlements

Civil strife and the Mongol invasions in 1241 and 1259, weakened and depopulated the small Polish principalities, and decreased the incomes of the princes, prompting them to encourage immigration, causing a massive inflow of German settlers, bringing with them German laws and customs. German settlements sprang up along the wide belt which was laid waste by the Mongols in 1241, comprising present Galicia and Southern Silesia.

Settlement was lucrative for those entrepreneurs who organized it. The entrepreneur who brought in a number of settlers, received, in addition to the compensation for his services, a piece of land for the colony of which he became came the chief (woyt), with a right to certain taxes. These rights could be passed on through inheritance or sold. In addition, he was the judge of the colony, was free from all duties except those of a knight and a tax collector, and responsible to nobody except to the prince.

The settlers, after dividing among themselves the land granted to them by the prince, proceeded to build a city with its town hall, a market-place, and church in the center. The streets radiated from the center, and the town was surrounded by a mound and ditch, beyond which lay arable fields, pastures, and woods. The settlers could build the towns in the way to which they were accustomed, and could govern themselves according to the practice of their native country.

Teutonic Knights

In 1226, Konrad I of Masovia invited the Teutonic Knights to help him fight the pagan Prussian people on the border of his lands. In the following decades, the Teutonic Order conquered large areas long the Baltic Sea coast and established their monastic state. When virtually all of the former heathen Baltic people had become Christians, the knights turned their attention to Poland and Lithuania, waging war with them for most of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries until their remaining state was converted into the Protestant Duchy of Prussia under the King of Poland in 1525.

The Acts of Cienia

The twelfth and thirteenth centuries were marked by the economic and social evolution of Poland into a Western Christian state. In 1228, the Acts of Cienia were passed and signed into law by Duke Wladyslaw III (1165?-1231). He promised to provide a "just and noble law according to the council of bishops and barons." The Acts of Cienia were similar to the English Magna Carta of 1215. The Act of Cienia guaranteed Wladyslaw that he would become the next king of Poland.

Jewish settlement

The Jews, persecuted all over Europe during the Crusades, fled to Poland where they were welcomed, settled in the towns, and began to carry on commerce and banking. An illustration of Poles' friendliness towards these newcomers is the statute of Kalisz, promulgated by Prince Boleslav in the year 1246 by which the Jews received every protection, of the law and which imposed heavy penalties for any insults to their cemeteries, synagogues and, other sanctuaries. About the same time Prince Henry IV of Wrocław (Breslau) imposed heavy penalties upon those who accused Jews of ritual murder - a common anti-Semitic slander across Europe at the time. Anyone who made such an accusation had to prove it by six witnesses, three Gentiles and three Jews, and in case of his inability to prove the charge in a satisfactory manner he was himself found guilty and subject to severe punishment.

The Black Death, one of the most deadly pandemics in human history, which affected most parts of Europe from 1347 to 1351, did not reach Poland.

Polish-Lithuanian Union

The regional division ended when Władysław I the Elbow-high (1261-1333) united the various principalities of Poland. His son Kazimierz the Great (1310-1370), the last of the Piast dynasty, considerably strengthened the country's position in both foreign and domestic affairs. Before his death in 1370, the heirless king arranged for his nephew, the Andegawen Louis of Hungary, to inherit the throne. In 1385, the Union of Krewo was signed between Louis' daughter Jadwiga and Jogaila, Grand Duke of Lithuania (later known as Władysław II Jagiełło) (1362-1434), beginning the Polish-Lithuanian Union and strengthening both nations in their shared opposition to the Teutonic Knights, and the growing threat of Grand Duchy of Moscow. Władysław, who was converted on his accession, introduced Christianity into Lithuania.

In 1410, a Polish-Lithuanian army inflicted a decisive defeat on the armies of Teutonic Knights in the Battle of Grunwald. After the Thirteen Years War (1454-1466) the knights' state was reduced to a Polish vassal.

Polish Golden Age

Polish culture and economy flourished under the Jagiellon dynasty, which originated in Lithuania and reigned over Poland from 1385 to 1572. The country produced such figures as astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus and poet Jan Kochanowski. The Nihil novi act adopted by the Polish Sejm (parliament) in 1505, transferred most of the legislative power from the monarch to the Sejm. This event marked the beginning of the period known as "Nobility Commonwealth" when the State was ruled by the "free and equal" Polish nobility.

Compared to other European nations, Poland was exceptional in its tolerance for religious dissent, allowing the country to avoid religious turmoil that spread over Western Europe in that time. Protestantism, which made many converts among the nobility in the middle years of the sixteenth century, ceased to be significant after 1600. During the Golden Age period, Poland became the largest country in Europe.

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Union of Lublin, signed July 1, 1569, in Lublin, Poland, united the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania into a single state. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was ruled by a single elected monarch who carried on the duties of Polish King and Grand Duke of Lithuania, and governed with a common Senate and parliament (the Sejm). By creating the largest state in Europe, Lithuania could hope to defend itself against its much more powerful neighbor Russia.

The szlachta (nobility) of Poland, far more numerous than in Western European countries, took pride in their freedoms and parliamentary system. Its quasi-democratic political system of Golden Liberty, albeit limited to nobility was mostly unprecedented in the history of Europe. When Sigismund II Augustus, the last of the Jagiellonians, died in 1572 without any heirs, the Polish nobility instituted a regime whereby kings were elected by the Sejm, then a bicameral body consisting of the lesser and greater nobility. Any member of the Sejm could prevent the passage of legislation with the liberum veto. The constitution enabled nobles to form military confederations. The first Polish election was held in 1573. Henri of Valois (Henryk Walezy), (Henri d'Anjou) who was the brother of the king of France, was the winner in a very disorderly election. Four months later, when his brother died, he left to occupy the throne of France.

Tatar invasions

From 1569, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth suffered a series of Tatar invasions, the goal of which was to loot, and capture slaves. Until the early eighteenth century, the Tatar khanate maintained a massive slave trade with the Ottoman Empire. Captives were on sale to Turkey and the Middle East. The borderland area to the south-east was in a state of semi-permanent warfare until the eighteenth century. Some researchers estimate that altogether more than three million people, predominantly Ukrainians but also Circassians, Russians, Belarusians and Poles, were captured and enslaved during the time of the Crimean Khanate.

The Deluge

The Deluge is the name assigned to a series of wars in the mid-to-late seventeenth century, starting with the Khmelnytskyi Uprising in 1648, which left the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in ruins.

Strife between Ukrainians and their Polish overlords, over the exploitation of peasants and suppression of the Orthodox church, began in the 1590s, spearheaded by the Cossacks. From 1648 to 1654, Bohdan Khmelnytskyi (1595—1657) led the largest of the Cossack uprisings] against the Commonwealth and the Polish king John II Casimir (1609-1672). Khmelnytskyi told his people that the Poles had sold them as slaves "into the hands of the accursed Jews," a reference to the Arenda system of renting out serfs to (sometimes) Jewish businessmen for three years at a time. This uprising finally led to a partition of Ukraine between Poland and Russia. Khmelnytsky sought help against the Poles in a treaty with Moscow in 1654. The Muscovites used as a pretext for occupation. Left-Bank Ukraine was eventually integrated into Russia as the Cossack Hetmanate.

Polish-Lithuanian noble Princes and Lithuanian nationists Janusz Radziwiłł and Bogusław Radziwiłł began negotiations with the Swedish king Charles X Gustav of Sweden (1622–1660), and signed the Kėdainiai Treaty in 1655, according to which the Radziwiłłs were to rule over two Duchies carved up from the lands of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, under Swedish vassalage (the Union of Kėdainiai). Meanwhile, members of the Polish nobility, thinking that John II Casimir of Poland was a weak king, or a Jesuit-King, encouraged Charles Gustav to claim the Polish crown. Soon, most areas had surrendered to the Swedish king. Several places resisted, the most remarkable being resistance at the Jasna Góra monastery, the location of the venerated Black Madonna of Częstochowa. The Swedes were driven back in 1657.

The Russians were defeated in 1662. The War for Ukraine ended with the treaty of Andrusovo (1667), with the help of Turkish intervention due to their claims in the Crimea.

The Deluge stopped the era of Polish tolerance, since most invaders were non-Catholic. During the Deluge, many thousands of Polish Jews fell victim to pogroms initiated by rebelling Cossacks. Poland-Lithuania stopped being an influential player in the politics of Europe. Its economy and growth was further damaged by the nobility's reliance on agriculture and serfdom, delaying the industrialization of the country.

Decline

The Elector of Saxony, Frederick Augustus I (1670-1733), who was elected king in 1697, contributed to the decline of Poland. He allied himself with Russia, became involved in war with Sweden for control of the Baltic, was removed from the throne by Sweden in 1704 (replaced by the Voivode of Poznan, Stanislaw Leszczynski), and returned to the throne in 1709. Conflict between Augustus and the Sejm brought Poland to the brink of civil war in 1717. Russian troops backed Augustus, resulting in the start of the Russian "Protectorate" period, in which Poland was forced to reduce its standing army. On Augustus' death, in 1733, Leszczynski was again elected king but the Russians interfered by sending in an army and re-running the election. Augustus' son, Frederick Augustus, was elected.

The 66 years of Saxon rule, from 1697 to 1763, drove the country to the brink of anarchy. Most ominous was the fact that in 1732 Russia, Prussia and Austria had entered into a secret alliance to maintain the paralysis of law and order within Poland—the "Alliance of the Three Black Eagles" since all three powers had a black eagle in their coat-of-arms.

The reign of Stanislaw August Poniatowski (1732-1798), a favorite of Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia, from 1764 to 1795, was controlled by Russia. Poniatowski was to become the last King of Poland. From 1768 to 1772, an anti-Russian rising known as the "Confederation of Bar" was crushed by the Russians. Over 5000 captured "szlachta" (the hereditary nobility) were sent to Siberia. Among the few who escaped was Kazimierz Pulaski (1746–1779) who was to play an important role in the United States' struggle for independence as "the father of American cavalry."

Enlightenment and constitution

The Age of Enlightenment arrived later in Poland than elsewhere in Western Europe, as the Polish bourgeoisie was weaker, and the szlachta (nobility) culture of Sarmatism, together with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth political system (Golden Freedoms), were in deep crisis. The period of the Polish Enlightenment started in the 1730s, and reached its height during the reign of last Polish king, Stanisław August Poniatowski, in the late eighteenth century, started declining with the third partition of Poland in 1795, and ended in 1822, when it was replaced by Romanticism.

Ideas of that period led to the Constitution of May 3, 1791, the second-oldest constitution, and other reforms (like the creation of the Komisja Edukacji Narodowej, which was the first ministry of education in the world. The ideas of the Polish Enlightenment had also significant impact abroad. From the Confederation of Bar (1768) through the period of the Great Sejm and until the tragic aftermath of the Constitution of the May 3, 1791, Poland experienced a large output of political, particularly constitutional, writing. Some of this literature was widely discussed in France and there it came to the attention of Thomas Jefferson.

Partitions of Poland

Opposition to the constitution came in the form of the Targowica Confederation, founded on April 27, 1792, in Saint Petersburg by a group of Polish-Lithuanian magnates who had the backing of Empress Catherine II of Russia. The magnates opposed provisions limiting the privileges of the nobility. Poland's neighbors viewed as dangerous measures that transformed the Commonwealth into a constitutional monarchy, and did want the rebirth of the strong Commonwealth.

On May 18, two Russian armies entered in Poland. The forces of the Targowica Confederation defeated the forces loyal to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Sejm and King Stanisław August Poniatowski in the War in Defense of the Constitution. Their victory precipitated the Second Partition of Poland and set the stage for the Third Partition and the final dissolution of the Commonwealth in 1795. This outcome came as a surprise to most of the Confederates, who had wished only to restore the status quo ante and had expected that the overthrow of the May 3rd Constitution would achieve that end.

Poland's name was erased from the map and its territories being divided between Russia, Prussia, and Austria. Russia gained most of the Commonwealth's territory including nearly all of the former Lithuania (except Podlasie and lands West from the Niemen river), Volhynia and Ukraine. Austria gained the populous southern region henceforth named Galicia–Lodomeria, named after the Duchy of Halicz and Volodymyr. In 1795, Austria also gained the land between Kraków and Warsaw, between Vistula river and Pilica river. Prussia acquired the western lands from the Baltic through Greater Poland to Kraków, as well as Warsaw and Lithuanian territories to the north-east (Augustów, Mariampol) and Podlasie. The last heroic attempt to save Poland's independence was a national uprising (1794) led by Tadeusz Kościuszko, however it was eventually quenched.

Duchy of Warsaw

Following the French emperor Napoleon I's defeat of Prussia, a Polish state was again set up in 1807 under French tutelage as the Duchy of Warsaw. When Austria was defeated in 1809, Lodomeria was added, giving the new state a population of some 3.75 million, a quarter of that of the former Commonwealth. Polish nationalists were to remain among the staunchest allies of the French as the tide of war turned against them, inaugurating a relationship that continued into the twentieth century.

Russian rule

With Napoleon's defeat, the Congress of Vienna in 1815 converted most of the Grand Duchy into a Kingdom of Poland ruled by the Russian Tsar before the Russian dynasty was deposed from the throne by the Kingdom's Parliament during the Polish-Russian War of 1830/1. After the January Uprising of 1863 the Kingdom was fully integrated into Russia proper. Several national uprisings were bloodily subdued by the partitioning powers. However, the striving of Polish patriots to regain their independence could not be extinguished. The opportunity for freedom appeared only after World War I when the oppressing states were defeated or weakened by a combination of each other, the Allied Powers, and internal revolt (such as the Russian Revolution).

World War I

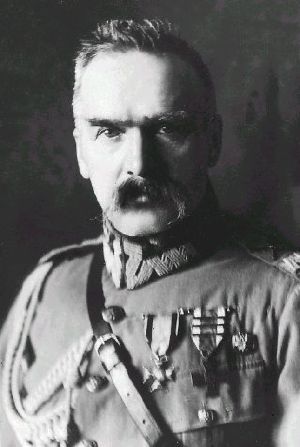

On the outbreak of World War I, the Poles found themselves conscripted into the armies of Germany, Austria and Russia, and forced to fight each other in a war that was not theirs. Jozef Pilsudski (1867-1935), who was to become Poland's first Chief of State, considered Russia as the greater enemy and formed Polish Legions to fight for Austria but independently. Other Galician Poles went to fight against the Italians when they entered the war in 1915, thus preventing any clash of conscience.

Second Polish Republic

Shortly after the surrender of Germany in November 1918, Poland regained its independence as the Second Polish Republic. It reaffirmed its independence after a series of military conflicts, the most notable being the Polish-Soviet War (1919–1921) when Poland inflicted a crushing defeat on the Red Army. On March 17, 1921, a modern, democratic constitution was voted in. The final borders of the Second Polish Republic were not established until 1922. The 1926 May Coup of Józef Piłsudski overthrew the government of President Stanisław Wojciechowski and Prime Minister Wincenty Witos, with a new government headed by the Lwów Polytechnic Professor, Kazimierz Bartel, and the Sanacja political movement. At first, Piłsudski was offered the presidency, but declined in favor of Ignacy Mościcki. Piłsudski, however, remained the most influential politician in Poland, and in fact became its dictator. His coalition government had the goal to return the nation to "moral health."

Poland at that time faced extensive war damage, a population one-third composed of wary national minorities, an economy largely under control of German industrial interests, and a need to reintegrate the three zones that had been forcibly kept apart during the era of partition. Nevertheless, Poland was able to rebuild the economy, so that by 1939 the country was the eighth-largest steel producer in the world and had developed mining, textiles, and chemical industries.

World War II

On August 23, 1939, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Ribbentrop–Molotov non-aggression pact, which secretly provided for the dismemberment of Poland into Nazi and Soviet-controlled zones. On September 1, 1939, Hitler ordered his troops into Poland. On September 17, Soviet troops marched into and then took control of most of the areas of eastern Poland having significant Ukrainian and Belarusian populations under the terms of this agreement. After Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, Poland was occupied by German troops. Warsaw capitulated on September 28, 1939. As agreed in the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, Poland was split into two zones, one occupied by Germany while the eastern provinces fell under the control of the Soviet Union.

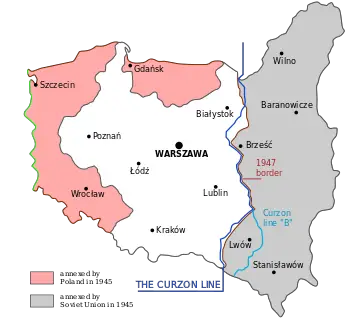

Of all the countries involved in the war, Poland lost the highest percentage of its citizens: over six million perished, half of them Polish Jews. The main German Nazi death camps were in Poland. Of a pre-war population of 3,300,000 Polish Jews, three million were killed during the Holocaust. Poland made the fourth-largest troop contribution to the Allied war effort, after the Soviets, the British and the Americans. At the war's conclusion, Poland's borders were shifted westwards, pushing the eastern border to the Curzon line. Meanwhile, the western border was moved to the Oder-Neisse line. The new Poland emerged 20 percent smaller by 29,900 square miles (77,500 square kilometers). This forced the migration of millions of people, most of whom were Poles, Germans, Ukrainians, and Jews.

Postwar Communist Poland

The Soviet Union instituted a new Communist government in Poland, analogous to much of the rest of the Eastern Bloc. Military alignment within the Warsaw Pact throughout the Cold War was also part of this change. The People's Republic of Poland (Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa) was officially proclaimed in 1952. In 1956, the régime of Władysław Gomułka became temporarily more liberal, freeing many people from prison and expanding some personal freedoms. Similar situation repeated itself in the 1970s under Edward Gierek, but most of the time persecution of communist opposition persisted.

Labor turmoil in 1980 led to the formation of the independent trade union "Solidarity" ("Solidarność"), which over time became a political force. It eroded the dominance of the Communist Party and by 1989 had triumphed in parliamentary elections. Lech Walesa, a Solidarity candidate, eventually won the presidency in 1990. The Solidarity movement heralded the collapse of communism across Eastern Europe.

Democratic Poland

A shock therapy program of Leszek Balcerowicz during the early 1990s enabled the country to transform its economy into a robust market economy. Despite temporary slumps in social and economic standards, Poland was the first post-communist country to reach its pre-1989 GDP levels. Most visibly, there were numerous improvements in other human rights, such as free speech. In 1991, Poland became a member of the Visegrad Group and joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance in 1999 along with the Czech Republic and Hungary. Poles then voted to join the European Union in a referendum in June 2003, with Poland becoming a full member on May 1, 2004.

Government and politics

Poland is a republic. The chief of state is a president who is elected by popular vote for a five-year term, and is eligible for a second term. The president appoints the prime minister and deputy prime ministers, as well as the cabinet according to the proposals of the prime minister, both typically from the majority coalition.

The Polish Parliament has two chambers. The lower chamber (Sejm) has 460 members, elected for a four-year term by proportional representation in multi-seat constituencies, with a five percent threshold (eight percent for coalitions, threshold waived for national minorities). The Senate (Senat) has 100 members elected for a four-year term in 40 multi-seat constituencies under a rare plurality bloc voting method where several candidates with the highest support are elected from each electorate. Suffrage is universal to those aged 18 years and over.

When sitting in joint session, members of the Sejm and Senate form the National Assembly. The National Assembly is formed on three occasions: Taking the oath of office by a new president, bringing an indictment against the president, and declaration of a president's permanent incapacity to exercise their duties due to the state of their health. Only the first type of sitting has occurred to date.

On the approval of the Senate, the Sejm also appoints the Ombudsman or the Commissioner for Civil Rights Protection for a five-year term. The Ombudsman guards the rights and liberties of Polish citizens and residents.

The judicial branch comprises the Supreme Court of Poland, the Supreme Administrative Court of Poland, the Constitutional Tribunal of Poland, and the State Tribunal of Poland. Poland has a mixture of continental (Napoleonic) civil law and holdover communist legal theory, although the latter is gradually being removed. The Constitutional Tribunal supervises the compliance of statutory law with the Constitution, and annuls laws which do not comply. Its rulings are final (since October 1999). Court decisions can be appealed to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

Administrative divisions

Poland's provinces are largely based on the country's historic regions, whereas those of the past two decades (till 1998) had been centered on and named after individual cities. The new units range in areas from under 3800 square miles (10,000km²) (Opole Voivodeship) to over 13,500 square miles (35,000km²) (Masovian Voivodeship). Voivodeships are governed by voivod governments, and their legislatures are called voivodeship sejmiks.

Poland is subdivided into 16 administrative regions, known as voivodeships. In turn, the voivodeships are divided into powiaty, second-level units of administration, equivalent to a county, district or prefecture in other countries, and finally communes, gminy.

Foreign relations

Poland has forged ahead on its economic reintegration with the West. Poland became a full member of NATO in 1999, and of the European Union in 2004. Poland became an associate member of the European Union (EU) and its defensive arm, the Western European Union (WEU) in 1994. In 1996 Poland achieved full OECD membership and submitted preliminary documentation for full EU membership. Poland joined the European Union in 2004, along with the other members of the Visegrád group.

Changes since 1989 have redrawn the map of central Europe. Poland has signed friendship treaties replacing links severed by the collapse of the Warsaw Pact. The Poles have forged special relationships with Lithuania and particularly Ukraine in an effort to firmly anchor these states to the West. Poland is a part of the multinational force in Iraq.

The military

Wojsko Polskie (Polish Army) is the name applied to the military forces of Poland. The name has been used since the early nineteenth century. The Polish armed forces are composed of five branches: Land Forces (Wojska Lądowe), Navy (Marynarka Wojenna), Air Force (Siły Powietrzne), Special Forces (Wojska Specjalne) and Territorial Defence Force (Wojska Obrony Terytorialnej) – a military component of the Polish armed forces created in 2016.

The most important mission of the armed forces is the defense of Polish territorial integrity and Polish interests abroad. Poland's national security goal is to further integrate with NATO and European defense, economic, and political institutions through the modernization and reorganization of its military. The armed forces were re-organized according to NATO standards, and since 2010 the transition to an entirely contract-based military has been completed. Compulsory military service for men of nine months was discontinued in 2008. Additionally, Poland's military embarked on a significant modernization phase, replacing dated equipment and purchasing new weapons systems.

Economy

Poland has pursued a policy of economic liberalization since 1990, making a successful transition from a state-directed economy to a primarily privately owned market economy. Its principal economic activities involve industry. Before World War II, industry was concentrated in coal, textile, chemical, machinery, iron, and steel sectors. Today, it has extended to fertilizers, petrochemicals, machine tools, electrical machinery, electronics, cars, and shipbuilding.

Export commodities include machinery and transport equipment, intermediate manufactured goods, miscellaneous manufactured goods, food and live animals. Export partners include Germany, Italy, France, United Kingdom, Czech Republic, and Russia. Import commodities include machinery and transport equipment, intermediate manufactured goods, chemicals, minerals, fuels, lubricants, and related materials. Import partners include Germany, Russia, Italy, Netherlands, and France.

Since 2004, European Union membership and access to EU structural funds provided a major boost to the economy. Since joining the EU, many Poles have left their country to work in other EU countries (particularly Ireland and the UK) because of high unemployment. An inefficient commercial court system, a rigid labor code, bureaucratic red tape, and persistent corruption kept the private sector from performing to its potential.

Demographics

Poles make up the large majority of the population. In terms of ethnicity, Poland has been regarded as a homogeneous state since the end of World War II. A wide-ranging Polish diaspora exists throughout Western and Eastern Europe, the Americas and Australia.

Due to the Holocaust and the flight and removal of Germans during and after World War II, Catholics make up about 90 percent of the population. The 1989 Polish constitution guarantee of freedom of religion allowed for the emergence of additional denominations.

Language

Polish is the official language. It belongs to the west Slavic group of languages of the Indo-European language family. Poles use the Latin alphabet. Literary Polish developed during the sixteenth century, and a new vocabulary was introduced from the nineteenth century, taking words from German, Latin, Russian, and English, with spelling alterations to reflect the Polish alphabet. There are regional dialects—Great Polish in the northwest, Kuyavian to the east, and Little Polish around Cracow.

Education

Children start primary school at age seven. Next is the lower secondary level consisting of three years in gymnasium, starting at the age of 13, which ends with an exam. This is followed by upper secondary level, which has several alternatives, the most common being the three years in a liceum or four years in a technikum. Both end with a maturity examination (matura, roughly equivalent to British A-levels examination and quite similar to French baccalauréat). There are several forms of tertiary education, leading to licencjat or inżynier (Polish equivalents of Bachelor's degree), magister (Polish equivalent of Master's degree) and eventually doktor (Polish equivalent of Ph.D. degree).

Culture

Architecture

Polish towns reflect the whole spectrum of European styles. Poland's Eastern frontiers once marked the outermost boundary of the influences of Western architecture on the continent. History has not been good to Poland's architectural monuments. However, a number of ancient edifices have survived: castles, churches, and stately buildings, sometimes unique in the regional or European context. Some of them have been painstakingly restored (the Wawel), or reconstructed after being destroyed in the Second World War (the Old Town and Royal Castle in Warsaw, the Old Towns of Gdańsk and Wrocław). Kazimierz Dolny on the Vistula is an example of a well-preserved medieval town.

Kraków ranks among the best preserved Gothic and Renaissance urban complexes in Europe. Polish church architecture deserves special attention. Complex Modernist Movement architecture designed and built in the 1930s exist in Katowice, Upper Silesia, while there are interesting examples of Socialist Realism constructed during the Communist regime.

Art

Jan Matejko's famous school of Historicist painting produced monumental portrayals of significant events in Polish history. Stanisław Witkiewicz was an ardent supporter of Realism in Polish art, its main representative being Jozef Chełmoński. The Młoda Polska (Young Poland) movement witnessed the birth of modern Polish art, and engaged in a great deal of formal experimentation, led by Jacek Malczewski (symbolism), Stanisław Wyspiański, Józef Mehoffer, and a group of Polish impressionists. The art of Tadeusz Makowski was influenced by cubism; while Władysław Strzemiński and Henryk Stażewski worked within the constructivist idiom. Distinguished 21st century artists include Roman Opałka, Leon Tarasewicz, Jerzy Nowosielski, Wojciech Siudmak, and Mirosław Bałka and Katarzyna Kozyra in the younger generation. The most celebrated Polish sculptors include Xawery Dunikowski, Katarzyna Kobro, Alina Szapocznikow and Magdalena Abakanowicz. Polish documentary photography has enjoyed worldwide recognition. In the 1960s the Polish Poster School was formed, with Henryk Tomaszewski and Waldemar Świerzy at its head.

Cuisine

Polish cuisine is a mixture of Slavic, Jewish and foreign culinary traditions. It is rich in meat, especially pork, cabbage (for example in the dish bigos), and spices, as well as different kinds of noodles and dumplings, the most notable of which are the pierogi. It is related to other Slavic cuisines in usage of kasza and other cereals, but was also under the heavy influence of Turkic, Germanic, Hungarian, Jewish, French, Italian or colonial cuisines of the past. Generally speaking, Polish cuisine is substantial. Poles allow themselves a generous amount of time to enjoy their meals, with some meals taking a number of days to prepare.

Notable foods in Polish cuisine include Polish sausage, red beet soup (borscht), Polish dumplings, tripe soup, cabbage rolls, Polish pork chops, Polish traditional stew, various potato dishes, a fast food sandwich zapiekanka, and many more. Traditional Polish desserts include Polish doughnuts, Polish gingerbread, and others.

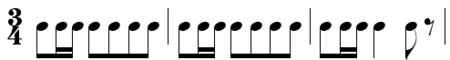

Dance

Dances of Poland include: the Polonaise, the krakowiak, the kujawiak, the mazurka, the oberek, and the troika. The polonaise is a rather slow dance of Polish origin, in 3/4 time. Its name is French for "Polish." The notation alla polacca on a score indicates that the piece should be played with the rhythm and character of a polonaise (e.g., the rondo in Beethoven's Triple Concerto op. 56 has this instruction).

Before Frédéric Chopin, the polonaise had a rhythm quite close to that of the Swedish semiquaver or sixteenth-note polska, and the two dances have a common origin. From Chopin onward, the polonaise developed a very solemn style, and has in that version become very popular in the classical music of several countries. One fine example of a polonaise is the well-known 'Heroic' Polonaise in A flat major, Op.53. Chopin composed this polonaise as the dream of a powerful, victorious and prosperous Poland. Polonaise is danced at carnival parties. There is also a German song, called "Polonäse Blankenese" from Gottlieb Wendehals alias Werner Böhm, which is often played at carnival festivals in Germany. Polonaise is always a first dance at a studniówka (means: "hundred-days"), the Polish equivalent of the senior prom, which is about 100 days before exams.

The Krakowiak, sometimes referred to as the Pecker Dance, is a fast, syncopated Polish dance from the region of Krakow and Little Poland. It became a popular ballroom dance in Vienna ("Krakauer") and Paris in the mid-nineteenth century.

The mazurka (Polish: mazurek, named after Poland's Mazury (Masuria) district, is a Polish folk dance in triple metre with a lively tempo. The dance became popular at Ballroom dances in the rest of Europe during the nineteenth century.

Several classical composers have written mazurkas, with the best known being the 57 composed by Frédéric Chopin for solo piano, the most famous of which is the Mazurka nr. 5. Henryk Wieniawski wrote two for violin with piano (the popular "Obertas," op. 19), and in the 1920s, Karol Szymanowski wrote a set of 20 for piano.

Literature

Polish literature originated before the fourteenth century. In the sixteenth century, the poetic works of Jan Kochanowski established him as a leading representative of European Renaissance literature. Baroque and Neo-Classicist belle letters made a significant contribution to the cementing of Poland's peoples of many cultural backgrounds.

The early nineteenth century novel "Manuscrit trouvé à Saragosse" by Count Jan Potocki, which survived in its Polish translation after the loss of the original in French, became a world classic. Wojciech Has, a film based on it, a favorite of Luis Buñuel, later became a cult film on university campuses. Poland's great Romantic literature flourished in the nineteenth century when the country had lost its independence. The poets Adam Mickiewicz, Juliusz Słowacki and Zygmunt Krasiński, the "Three Bards," became the spiritual leaders of a nation deprived of its sovereignty, and prophesied its revival. The novelist Henryk Sienkiewicz, who won the Nobel Prize in 1905, eulogised Poland's history.

In the early twentieth century, the Kresy Marchlands of Poland's Eastern regions were the location of the works of Bruno Schulz, Bolesław Leśmian, and Józef Czechowicz. In the south of Poland, Zakopane was the birthplace of the avant-garde works of Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (Witkacy). Władysław Reymont was awarded the 1924 Nobel prize in literature for his novel Chłopi (The Peasants).

After World War II, many Polish writers found themselves in exile, with many of them clustered around the Paris-based "Kultura" publishing venture run by Jerzy Giedroyc. The group of emigre writers included Witold Gombrowicz, Gustaw Herling-Grudziński, Czesław Miłosz, and Sławomir Mrożek.

Zbigniew Herbert, Tadeusz Różewicz, Czeslaw Milosz (Nobel Prize in Literature 1980), and Wisława Szymborska (Nobel Prize in Literature 1996) are among the most outstanding twentieth century Polish poets, as well as novelists and playwrights Witold Gombrowicz, Sławomir Mrożek, and Stanisław Lem (science fiction).

Music

The music of Fryderyk Chopin, inspired by Polish tradition and folklore, conveys the quintessence of Romanticism. Since 1927, the International Chopin Piano Competition has been held every five years in Warsaw. Polish classical music is also represented by composers like Karol Szymanowski, Mieczysław Karłowicz, Witold Lutosławski, Wojciech Kilar, Henryk Mikołaj Górecki, and Krzysztof Penderecki. Contemporary Polish jazz has fans in many countries. The best-known jazzmen are Krzysztof Komeda, Michał Urbaniak, Adam Makowicz, and Tomasz Stańko. Successful composers of film music include Jan A.P. Kaczmarek, Wojciech Kilar, Czesław Niemen and Zbigniew Preisner. Famous modern singers, musicians and bands from Poland include Behemoth, Myslovitz, SBB, Riverside, Edyta Górniak, Lady Pank, Anita Lipnicka and Ich Troje.

Theatre

The Polish avant-garde theatre is world-famous, with Jerzy Grotowski as its most innovative and creative representative. One of the most original twentieth-century theatre personalities was Tadeusz Kantor, painter, theoretician of drama, stage designer, and playwright, his ideas finding their culmination in the theatre of death and his most recognized production being "Umarła klasa" (Dead Class).

Sport

Poland's national sports include football, volleyball, hockey, basketball and handball. Soccer is the country's most popular sport, with a rich history of international competition. Poland has also made a distinctive mark in motorcycle speedway racing thanks to Tomasz Gollob, a highly successful Polish rider. The Polish mountains are the ideal venue for hiking, skiing and mountain biking and attract millions of tourists every year from all over the world. Baltic beaches and resorts are popular locations for fishing, canoeing, kayaking and a broad-range of other water-themed sports.

Historical maps of Poland

Notes

- ↑ CIA, Poland World Factbook. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ↑ Statistical Bulletin No 11/2022 Statistics Poland. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Poland) International Monetary Fund. Retrieved January 2, 2024,

- ↑ Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income - EU-SILC survey Eurostat. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Biskupski, Mieczysław B. The History of Poland. The Greenwood histories of the modern nations. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0313305719

- Chisholm, Jane. Timelines of World History. Usborne, 2016. ISBN 978-1474903936

- Curtis, Glenn E. Poland a Country Study. Area handbook series. Washington, DC: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, 1994. ISBN 978-0844408279

- Davies, Norman. Heart of Europe a Short History of Poland. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Clarendon Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0198730606

- Lemnis, Maria, and Henryk Vitry. Old Polish Traditions in the Kitchen and at the Table. Hippocrene international cookbook series. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1996. ISBN 978-0781804882

- Teeple, J. B. Timelines of World History. Publisher: DK Adult, 2002. ISBN 978-0751337426

External links

All links retrieved January 2, 2024.

- Poland CIA World FactBook

- Poland country profile BBC

- Poland U.S. Department of State

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Poland history

- Warsaw history

- History_of_Poland history

- Prehistory_of_Poland_until_966 history

- Deluge_history history

- Enlightenment_in_Poland history

- History_of_Poland_1795-1918 history

- History_of_Poland_1918-1939 history

- Politics_of_Poland history

- Foreign_relations_of_Poland history

- Poles history

- Education_in_Poland history

- Culture_of_Poland history

- Polish_cuisine history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.