Pope Leo X, born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici (December 11, 1475 - December 1, 1521) was Pope from 1513 to his death. He is known primarily for his papal bull against Martin Luther and subsequent failure to stem the Protestant Reformation, which began during his reign when Martin Luther (1483–1546) published the 95 Theses and nailed them to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg. He was the second son of Lorenzo de' Medici, the most famous ruler of the Florentine Republic, and Clarice Orsini. His cousin, Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici, would become a pope, Pope Clement VII (1523–34). He was a member of the powerful Medici family.

The remark "It has served us well, this myth of Christ" is often attributed to him, despite the fact that it first appears in John Bale's fiercely antipapal treatise, The Pageant of the Popes (1575).[1] Leo's refusal to concede the truth of Luther's criticisms, and to promote necessary reform, caused the birth of Protestant Christianity, since Luther did not set out to found a new church but to change the existing one. It would take more diplomatic and spiritually mature successors to the throne of St. Peter to undertake the Counter-Reformation in which many reforms advocated by Luther were carried out. Leo's extravagant expenditure left the papacy in debt.

Biography

Early career

Giovanni de' Medici was born in Florence, Italy.

He was destined from his birth for the church, he received the tonsure at the age of six and was soon loaded with rich benefices and preferments. His father prevailed on Innocent VIII to name him cardinal-deacon of Santa Maria in Domnica in March 1489, although he was not allowed to wear the insignia or share in the deliberations of the college until three years later. Meanwhile he received a careful education at Lorenzo's brilliant humanistic court under such men as Angelo Poliziano, Pico della Mirandola, Marsilio Ficino and Bernardo Dovizio Bibbiena. From 1489 to 1491, he studied theology and canon law at Pisa under Filippo Decio and Bartolomeo Sozzini.

On March 23, 1492, he was formally admitted into the sacred college and took up his residence at Rome, receiving a letter of advice from his father which ranks among the wisest of its kind. The death of Lorenzo on the following April 8, however, called the seventeen year old cardinal to Florence. He participated in the conclave of 1492 which followed the death of Innocent VIII, and opposed the election of Cardinal Borgia. He made his home with his elder brother Piero at Florence throughout the agitation of Savonarola and the invasion of Charles VIII of France, until the uprising of the Florentines and the expulsion of the Medici in November 1494. While Piero found refuge at Venice and Urbino, Cardinal Giovanni traveled in Germany, in the Netherlands and in France.

In May 1500, he returned to Rome, where he was received with outward cordiality by Alexander VI, and where he lived for several years immersed in art and literature. In 1503, he welcomed the accession of Julius II to the pontificate; the death of Piero de' Medici in the same year made Giovanni head of his family. On October 1, 1511, he was appointed papal legate of Bologna and the Romagna, and when the Florentine republic declared in favor of the schismatic Pisans Julius II sent him against his native city at the head of the papal army. This and other attempts to regain political control of Florence were frustrated, until a bloodless revolution permitted the return of the Medici. Giovanni's younger brother Giuliano was placed at the head of the republic, but the cardinal actually managed the government.

Election to Papacy

Julius II died in February 1513, and the conclave, after a stormy seven-day session, united on Cardinal de' Medici as the candidate of the younger cardinals. He was elected on March 9, but he was proclaimed on March 11. He was ordained to the priesthood on March 15, consecrated bishop on 17, and enthroned with the name of Leo X on 19. There is no evidence of simony in the conclave, and Leo's election was hailed with delight by at least some of the Romans on account of his reputation in Rome for liberality, kindliness and love of peace. Following the example of many of his predecessors, he promptly repudiated his election "capitulation" as an infringement on the divinely bestowed prerogatives of the Holy See.

Many problems confronted Leo X on his accession. These included the need to preserve the papal conquests which he had inherited from Alexander VI and Julius II; the minimization of foreign influence, whether French, Spanish or German, in Italy; the need to put an end to the Pisan schism and settle the other troubles relating to the French invasion; the restoration of the French Church to Catholic unity, by abolishing the pragmatic sanction of Bourges, and bringing to a successful close the Lateran council convoked by his predecessor. He had also to face the victorious advance of the Turks as well as the disagreeable wranglings of German humanists. Other problems connected with his family interests served to complicate the situation and eventually to prevent the successful consummation of many, many of his plans.

Role in Italian Wars

At the very time of Leo's accession Louis XII of France, in alliance with Venice, was making a determined effort to regain the duchy of Milan, and the pope, after fruitless endeavours to maintain peace, joined the league of Mechlin on April 5, 1513, with the emperor Maximilian I, Ferdinand I of Spain, and Henry VIII of England. The French and Venetians were at first successful, but were defeated in June at the Battle of Novara. The Venetians continued the struggle until October. On December 9, the fifth Lateran council, which had been reopened by Leo in April, ratified the peace with Louis XII and officially registered the conclusion of the Pisan schism.

While the council was engaged in planning a crusade and in considering the reform of the clergy, a new crisis occurred between the pope and the new king of France, Francis I, an enthusiastic young prince, dominated by the ambition of recovering Milan and the Kingdom of Naples. Leo at once formed a new league with the emperor and the king of Spain, and to ensure English support made Thomas Wolsey a cardinal. Francis entered Italy in August and on September 14, won the battle of Marignano. The pope in October signed an agreement binding him to withdraw his troops from Parma and Piacenza, which had been previously gained at the expense of the duchy of Milan, on condition of French protection at Rome and Florence. The king of Spain wrote to his ambassador at Rome "that His Holiness had hitherto played a double game and that all his zeal to drive the French from Italy had been only a mask;" this reproach seemed to receive some confirmation when Leo X held a secret conference with Francis at Bologna in December 1515. The ostensible subjects under consideration were the establishment of peace between France, Venice and the Empire, with a view to an expedition against the Turks, and the ecclesiastical affairs of France. Precisely what was arranged is unknown. During these two or three years of incessant political intrigue and warfare it was not to be expected that the Lateran council should accomplish much. Its three main objectives, the peace of Christendom, the crusade (against the Turks), and the reform of the church, could be secured only by general agreement among the powers, and either Leo or the council, or both, failed to secure such agreement. Its most important achievements were the registration at its eleventh sitting (9 December 1516) of the abolition of the pragmatic sanction, which the popes since Pius II had unanimously condemned, and the confirmation of the concordat between Leo X and Francis I, which was destined to regulate the relations between the French Church and the Holy See until the Revolution. Leo closed the council on 16 March 1517. It had ended the Pisan schism, ratified the censorship of books introduced by Alexander VI and imposed tithes for a war against the Turks. It raised no voice against the primacy of the pope.

War of Urbino

The year which marked the close of the Lateran council was also signalized by Leo's war against the duke of Urbino Francesco Maria I della Rovere. The pope was proud of his family and had practised nepotism from the outset. His cousin Giulio, who subsequently became pope as Clement VII, he had made the most influential man in the curia, naming him archbishop of Florence, cardinal and vice-chancellor of the Holy See. Leo had intended his younger brother Giuliano and his nephew Lorenzo for brilliant secular careers. He had named them Roman patricians; the latter he had placed in charge of Florence; the former, for whom he planned to carve out a kingdom in central Italy of Parma, Piacenza, Ferrara and Urbino, he had taken with himself to Rome and married to Filiberta of Savoy. The death of Giuliano in March 1516, however, caused the pope to transfer his ambitions to Lorenzo. At the very time (December 1516) that peace between France, Spain, Venice and the Empire seemed to give some promise of a Christendom united against the Turks, Leo was preparing an enterprise as unscrupulous as any of the similar exploits of Cesare Borgia. He obtained 150,000 ducats towards the expenses of the expedition from Henry VIII of England, in return for which he entered the imperial league of Spain and England against France.

The war lasted from February to September 1517, and ended with the expulsion of the duke and the triumph of Lorenzo; but it revived the allegedly nefarious policy of Alexander VI, increased brigandage and anarchy in the Papal States, hindered the preparations for a crusade and wrecked the papal finances. Francesco Guicciardini reckoned the cost of the war to Leo at the prodigious sum of 800,000 ducats. The new duke of Urbino was the Lorenzo de' Medici to whom Machiavelli addressed The Prince. His marriage in March 1518 was arranged by the pope with Madeleine la Tour d'Auvergne, a royal princess of France, whose daughter was the Catherine de' Medici celebrated in French history.

The war of Urbino was further marked by a crisis in the relations between pope and cardinals. The sacred college had allegedly grown especially worldly and troublesome since the time of Sixtus IV, and Leo took advantage of a plot of several of its members to poison him, not only to inflict exemplary punishments by executing one and imprisoning several others, but also to make a radical change in the college. On July 3, 1517, he published the names of thirty-one new cardinals, a number almost unprecedented in the history of the papacy. Among the nominations were notables such as Lorenzo Campeggio, Giambattista Pallavicini, Adrian of Utrecht (the future Pope Adrian VI), Thomas Cajetan, Cristoforo Numai and Egidio Canisio. The naming of seven members of prominent Roman families, however, reversed the policy of his predecessor which had kept the political factions of the city out of the curia. Other promotions were for political or family considerations or to secure money for the war against Urbino. The pope was accused of having exaggerated the conspiracy of the cardinals for purposes of financial gain, but most of such accusations appear to be unsubstantiated.

Leo, meanwhile, felt the need of staying the advance of the warlike Ottoman sultan, Selim I, who was threatening western Europe, and made elaborate plans for a crusade. A truce was to be proclaimed throughout Christendom; the pope was to be the arbiter of disputes; the emperor and the king of France were to lead the army; England, Spain and Portugal were to furnish the fleet; and the combined forces were to be directed against Constantinople. Papal diplomacy in the interests of peace failed, however; Cardinal Wolsey made England, not the pope, the arbiter between France and the Empire; and much of the money collected for the crusade from tithes and indulgences was spent in other ways. In 1519, Hungary concluded a three years' truce with Selim I, but the succeeding sultan, Suleyman the Magnificent, renewed the war in June 1521 and on August 28, captured the citadel of Belgrade. The pope was greatly alarmed, and although he was then involved in war with France he sent about 30,000 ducats to the Hungarians. Leo treated the Uniate Greeks with great loyalty, and by bull of May 18, 1521, forbade Latin clergy to celebrate mass in Greek churches and Latin bishops to ordain Greek clergy.

These provisions were later strengthened by Clement VII and Paul III and went far to settle the chronic disputes between the Latins and Uniate Greeks.

Reformation and last years

Leo was disturbed throughout his pontificate by alleged heresy and schisms, especially the kulturkampf touched off by Martin Luther. Literally, this refers to a cultural struggle, and refers to the scope of the church's influence within society. Luther's use of the German language, too, challenged the Church's ability to act as gatekeeper of scripture, since people who did not know latin could now read and interpret the Bible without the need of a priest as mediator.

Schism between Reuchlin and Pfefferkorn regarding the banning of Hebrew books

The dispute between the Hebraist Johann Reuchlin and Johannes Pfefferkorn relative to the Talmud and other Jewish books, as well as censorship of such books, was referred to the pope in September 1513. He in turn referred it to the bishops of Spires and Worms, who gave decision in March 1514 in favor of Reuchlin. After the appeal of the inquisitor-general, Hochstraten, and the appearance of the Epistolae obscurorum virorum, however, Leo annulled the decision (June 1520) and imposed silence on Reuchlin. In the end he allowed the Talmud to be printed.

The Protestant Schism

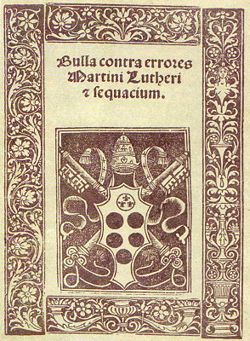

Against the misconduct from some servants of the church, the Augustinian monk Martin Luther posted (October 31, 1517) his famous ninety-five theses on the church door at Wittenberg, which successively escalated to a widespread revolt against the church. Although Leo did not fully comprehend the importance of the movement, he directed (February 3, 1518) the vicar-general of the Augustinians to impose silence on the monks. On May 30, Luther sent an explanation of his theses to the pope; on August 7, he was summoned to appear at Rome. An arrangement was effected, however, whereby that summons was canceled, and Luther went to Augsburg in October 1518 to meet the papal legate, Cardinal Cajetan, who was attending the imperial diet convened by the emperor Maximilian to impose the tithes for the Turkish war and to elect a king of the Romans; but neither the arguments of the educated cardinal, nor the dogmatic papal bull of November 9 requiring all Christians to believe in the pope's power to grant indulgences, moved Luther to retract. A year of fruitless negotiation followed, during which controversy over the pamphlets of the reformer set all Germany on fire. A papal bull of June 15, 1520, which condemned forty-one propositions extracted from Luther's teachings, was taken to Germany by Eck in his capacity of apostolic nuncio, published by him and the legates Alexander and Caracciolo, and burned by Luther on December 10, at Wittenberg. Leo then formally excommunicated Luther by bull of the January 3, 1521; in a brief the Pope also directed the emperor to take energetic measures against heresy. On May 26, 1521, the emperor signed the edict of the diet of Worms, which placed Luther under the ban of the Empire; on 21 of the same month Henry VIII of England (who was later to split from Catholicism himself) sent to Leo his book against Luther on the seven sacraments. The pope, after careful consideration, conferred on the king of England the title "Defender of the Faith" by bull of October 11, 1521. Neither the imperial edict nor the work of Henry VIII halted the Lutheran movement, and Luther himself, safe in the solitude of the Wartburg, survived Leo X.

It was under Leo X also that the Protestant movement emerged in Scandinavia. The pope had repeatedly used the rich northern benefices to reward members of the Roman curia, and towards the close of the year 1516 he sent the grasping and impolitic Arcimboldi as papal nuncio to Denmark to collect money for St Peter's. King Christian II took advantage of the growing dissatisfaction on the part of the native clergy toward the papal government, and of Arcimboldi's interference in the Swedish revolt, in order to expel the nuncio and summon (1520) Lutheran theologians to Copenhagen. Christian approved a plan by which a formal state church should be established in Denmark, all appeals to Rome should be abolished, and the king and diet should have final jurisdiction in ecclesiastical causes. Leo sent a new nuncio to Copenhagen (1521) in the person of the Minorite Francesco de Potentia, who readily absolved the king and received the rich bishopric of Skara. The pope or his legate, however, took no steps to remove abuses or otherwise reform the Scandinavian churches. (Some Scandinavian countries still have Protestant state churches.)

Italian politics

That Leo did not do more to check the anti-papal rebellion in Germany and Scandinavia is to be partially explained by the political complications of the time, and by his own preoccupation with papal and Medicean politics in Italy. The death of the emperor Maximilian, in 1519, had seriously affected the situation. Leo vacillated between the powerful candidates for the succession, allowing it to appear at first that he favoured Francis I while really working for the election of some minor German prince. He finally accepted Charles V of Spain as inevitable; and the election of Charles (28 June 1519) revealed Leo's desertion of his French alliance, a step facilitated by the death at about the same time of Lorenzo de' Medici and his French wife.

Leo was now anxious to unite Ferrara, Parma and Piacenza to the States of the Church. An attempt late in 1519 to seize Ferrara failed, and the pope recognized the need of foreign aid. In May 1521, a treaty of alliance was signed at Rome between him and the emperor. Milan and Genoa were to be taken from France and restored to the Empire, and Parma and Piacenza were to be given to the Church on the expulsion of the French. The expense of enlisting 10,000 Swiss was to be borne equally by pope and emperor. Charles took Florence and the Medici family under his protection and promised to punish all enemies of the Catholic faith. Leo agreed to invest Charles with Naples, to crown him emperor, and to aid in a war against Venice. It was provided that England and the Swiss might join the league. Henry VIII announced his adherence in August. Francis I had already begun war with Charles in Navarre, and in Italy, too, the French made the first hostile movement (June 23, 1521). Leo at once announced that he would excommunicate the king of France and release his subjects from their allegiance unless Francis laid down his arms and surrendered Parma and Piacenza. The pope lived to hear the joyful news of the capture of Milan from the French and of the occupation by papal troops of the long-coveted provinces (November 1521).

Death

Having fallen ill of malaria, Leo X died on 1 December 1521, so suddenly that the last sacraments could not be administered; but the contemporary suspicions of poison were unfounded. He was buried in Santa Maria sopra Minerva.

Leo was followed as Pope by Adrian VI.

Behavior as Pope and patron of arts

When he became Pope, Leo X is reported to have said to his brother Giuliano: "Since God has given us the papacy, let us enjoy it." The Venetian ambassador who related this of him was not unbiased, nor was he in Rome at the time, nevertheless the phrase illustrates fairly the Pope's pleasure-loving nature and the lack of seriousness that characterized him. And enjoy he did, traveling around Rome at the head of a lavish parade featuring panthers, jesters, and Hanno, a white elephant. According to Alexander Dumas

Under his pontificate, Christianity assumed a pagan character, which, passing from art into manners, gives to this epoch a strange complexion. Crimes for the moment disappeared, to give place to vices; but to charming vices, vices in good taste, such as those indulged in by Alcibiades and sung by Catullus.[2]

Leo X was also lavish in charity: retirement homes, hospitals, convents, discharged soldiers, pilgrims, poor students, exiles, cripples, the sick, and the unfortunate of every description were generously remembered, and more than 6,000 ducats were annually distributed in alms.

His extravagance offended not only people like Martin Luther, but also some cardinals, who, led by Alfonso Petrucci of Siena, plotted an assassination attempt. Eventually, Pope Leo found out who these people were, and had them followed. The conspirators died of "food poisoning." Some people argue that Leo X and his followers simply concocted the assassination charges in a moneymaking scheme to collect fines from the various wealthy cardinals Leo X detested.

While yet a cardinal, he restored the church of Santa Maria in Domnica after Raphael's designs; and as pope he had San Giovanni dei Fiorentini, on the Via Giulia, built, after designs by Jacopo Sansovino and pressed forward the work on St Peter's and the Vatican under Raphael and Agostino Chigi.

His constitution of November 5, 1513, reformed the Roman university, which had been neglected by Julius II. He restored all its faculties, gave larger salaries to the professors, and summoned distinguished teachers from afar; and, although it never attained to the importance of Padua or Bologna, it nevertheless possessed in 1514 a faculty (with a good reputation) of eighty-eight professors. Leo called Theodore Lascaris to Rome to give instruction in Greek, and established a Greek printing-press from which the first Greek book printed at Rome appeared in 1515. He made Raphael custodian of the classical antiquities of Rome and the vicinity. The distinguished Latinists Pietro Bembo and Jacopo Sadoleto were papal secretaries, as well as the famous poet Bernardo Accolti. Other poets such as Marco Girolamo Vida, Gian Giorgio Trissino, and Bibbiena, writers of novelle like Matteo Bandello, and a hundred other literati of the time were bishops, or papal scriptors or abbreviators, or in other papal employ.

Leo's lively interest in art and literature, to say nothing of his natural liberality, his alleged nepotism, his political ambitions and necessities, and his immoderate personal luxury, exhausted within two years the hard savings of Julius II, and precipitated a financial crisis from which he never emerged and which was a direct cause of most of what, from a papal point of view, were calamities of his pontificate. He created many new offices and sold them, a move seen by later Catholics as being "shameless." He sold cardinals' hats. He sold membership in the "Knights of Peter." He borrowed large sums from bankers, curials, princes and Jews. The Venetian ambassador Gradenigo estimated the paying number of offices on Leo's death at 2,150, with a capital value of nearly 3,000,000 ducats and a yearly income of 328,000 ducats. Marino Giorgi reckoned the ordinary income of the pope for the year 1517 at about 580,000 ducats, of which 420,000 came from the States of the Church, 100,000 from annates, and 60,000 from the composition tax instituted by Sixtus IV. These sums, together with the considerable amounts accruing from indulgences, jubilees, and special fees, vanished as quickly as they were received. Then the pope resorted to pawning palace furniture, table plate, jewels, even statues of the apostles. Several banking firms and many individual creditors were ruined by the death of the pope. His self-indulgence expressed itself in Raphael's first commission under Leo, which was to "immortalize the actions of Leo's namesakes in history: Leo I who had halted Attila, Leo III who had crowned Charlemagne, Leo IV who had built the Leonine City—each was given the features of Giovanni de' Medici."[3]

Legacy

Several minor events of Leo's pontificate are worthy of mention. He was particularly friendly with King Manuel I of Portugal on account of the latter's missionary enterprises in Asia and Africa. His concordat with Florence (1516) guaranteed the free election of the clergy in that city. His constitution of 1 March 1519 condemned the king of Spain's claim to refuse the publication of papal bulls. He maintained close relations with Poland because of the Turkish advance and the Polish contest with the Teutonic Knights. His bull of July 1, 1519, which regulated the discipline of the Polish Church, was later transformed into a concordat by Clement VII. Leo showed special favours to the Jews and permitted them to erect a Hebrew printing-press at Rome. He approved the formation of the Oratory of Divine Love, a group of pious men at Rome which later became the Theatine Order, and he canonized Francis of Paola. He will, however, mainly be remembered for his extravagant expenditure and for his clash with Martin Luther, which effectively caused the Protestant Reformation.

See also

Notes

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chamberlain, E.R The Bad Popes. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1993. ISBN 9780880291163.

- Doak, Robin S. Pope. Leo X Opponent of the Reformation. Signature lives. Minneapolis, MN: Compass Point Books, 2006. ISBN 9780756515942.

- Luther, Martin. Luther's Correspondence and Other Contemporary Letters. Tr. and ed. by Preserved Smith, Charles Michael Jacobs. Philadelphia, PA: The Lutheran Publication Society, 1913, 1918. ISBN 978-1597526012.

- Pastor, Ludwig von. History of the Popes from the Close of the Middle Ages; Drawn from the Secret Archives of the Vatican and other Original Sources. St. Louis: B.Herder, 1898.

- Vaughan, Herbert M. The Medici Popes. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1908. ISBN 978-0548191927.

- Zophy, Jonathan W. A Short History of Renaissance and Reformation Europe Dances over Fire and Water. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2003. ISBN 9780139593628.

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved October 25, 2022.

- Pope Leo X Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Vita de Leonis X life in Latin by Paulus Jovius

Popes of the Catholic Church

Peter

Linus

Anacletus

Clement I

Evaristus

Alexander I

Sixtus I

Telesphorus

Hyginus

Pius I

Anicetus

Soter

Eleuterus

Victor I

Zephyrinus

Callixtus I

Urban I

Pontian

Anterus

Fabian

Cornelius

Lucius I

Stephen I

Sixtus II

Dionysius

Felix I

Eutychian

Caius

Marcellinus

Marcellus I

Eusebius

Miltiades

Sylvester I

MarkJulius I

Liberius

Damasus I

Siricius

Anastasius I

Innocent I

Zosimus

Boniface I

Celestine I

Sixtus III

Leo I

Hilarius

Simplicius

Felix III

Gelasius I

Anastasius II

Symmachus

Hormisdas

John I

Felix IV

Boniface II

John II

Agapetus I

Silverius

Vigilius

Pelagius I

John III

Benedict I

Pelagius II

Gregory I

Sabinian

Boniface III

Boniface IV

Adeodatus IBoniface V

Honorius I

Severinus

John IV

Theodore I

Martin I

Eugene I

Vitalian

Adeodatus II

Donus

Agatho

Leo II

Benedict II

John V

Conon

Sergius I

John VI

John VII

Sisinnius

Constantine

Gregory II

Gregory III

Zachary

Stephen II

Paul I

Stephen III

Adrian I

Leo III

Stephen IV

Paschal I

Eugene II

Valentine

Gregory IV

Sergius IILeo IV

Benedict III

Nicholas I

Adrian II

John VIII

Marinus I

Adrian III

Stephen V

Formosus

Boniface VI

Stephen VI

Romanus

Theodore II

John IX

Benedict IV

Leo V

Sergius III

Anastasius III

Lando

John X

Leo VI

Stephen VII

John XI

Leo VII

Stephen VIII

Marinus II

Agapetus II

John XII

Leo VIII

Benedict V

John XIII

Benedict VI

Benedict VII

John XIVJohn XV

Gregory V

Sylvester II

John XVII

John XVIII

Sergius IV

Benedict VIII

John XIX

Benedict IX

Sylvester III

Benedict IX

Gregory VI

Clement II

Benedict IX

Damasus II

Leo IX

Victor II

Stephen IX

Nicholas II

Alexander II

Gregory VII

Victor III

Urban II

Paschal II

Gelasius II

Callixtus II

Honorius II

Innocent II

Celestine II

Lucius II

Eugene III

Anastasius IV

Adrian IV

Alexander IIILucius III

Urban III

Gregory VIII

Clement III

Celestine III

Innocent III

Honorius III

Gregory IX

Celestine IV

Innocent IV

Alexander IV

Urban IV

Clement IV

Gregory X

Innocent V

Adrian V

John XXI

Nicholas III

Martin IV

Honorius IV

Nicholas IV

Celestine V

Boniface VIII

Benedict XI

Clement V

John XXII

Benedict XII

Clement VI

Innocent VI

Urban V

Gregory XI

Urban VI

Boniface IX

Innocent VIIGregory XII

Martin V

Eugene IV

Nicholas V

Callixtus III

Pius II

Paul II

Sixtus IV

Innocent VIII

Alexander VI

Pius III

Julius II

Leo X

Adrian VI

Clement VII

Paul III

Julius III

Marcellus II

Paul IV

Pius IV

Pius V

Gregory XIII

Sixtus V

Urban VII

Gregory XIV

Innocent IX

Clement VIII

Leo XI

Paul V

Gregory XV

Urban VIII

Innocent X

Alexander VII

Clement IXClement X

Innocent XI

Alexander VIII

Innocent XII

Clement XI

Innocent XIII

Benedict XIII

Clement XII

Benedict XIV

Clement XIII

Clement XIV

Pius VI

Pius VII

Leo XII

Pius VIII

Gregory XVI

Pius IX

Leo XIII

Pius X

Benedict XV

Pius XI

Pius XII

John XXIII

Paul VI

John Paul I

John Paul II

Benedict XVI

FrancisCurrently: Francis Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

.JPG/250px-Ara_Coeli_(12).JPG)