Portugal

| República Portuguesa Portuguese Republic |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Anthem: "A Portuguesa" "The Portuguese Anthem" |

||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Lisbon 38°46′N 9°9′W | |||

| Official languages | Portuguese | |||

| Recognized regional languages | Mirandese1 | |||

| Ethnic groups (2007) | 96.87% Portuguese and 3.13% other ethnicities (Cape Verdeans, Brazilians, Ukrainians, Angolans, etc.).[1] | |||

| Demonym | Portuguese | |||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic | |||

| - | President | Aníbal Cavaco Silva (PSD) | ||

| - | Prime Minister | Pedro Passos Coelho (PSD) | ||

| - | Assembly President | Assunção Esteves (PSD) | ||

| Formation | Conventional date for Independence is 1139 | |||

| - | Founding | 868 | ||

| - | Re-founding | 1095 | ||

| - | De facto sovereignty | 24 June 1128 | ||

| - | Kingdom | 25 July 1139 | ||

| - | Recognized | 5 October 1143 | ||

| - | Papal Recognition | 23 May 1179 | ||

| - | Restoration of independence | 1 December 1640 | ||

| - | Restoration of independence recognized | 13 February 1668 | ||

| - | Republic | 5 October 1910 | ||

| Area | ||||

| - | Total | km² (110th) 35,645 sq mi |

||

| - | Water (%) | 0.5 | ||

| Population | ||||

| - | 2011 estimate | 10,647,763[2] (77th) | ||

| - | 2011 census | 10,555,853[3] | ||

| - | Density | 115/km² (96th) 298/sq mi |

||

| GDP (PPP) | 2010 estimate | |||

| - | Total | $247.037 billion[4] (48th) | ||

| - | Per capita | $23,222[4] (39th) | ||

| GDP (nominal) | 2010 estimate | |||

| - | Total | $229.336 billion[4] (37th) | ||

| - | Per capita | $21,558[4] (32nd) | ||

| Gini (2009) | 33.7[5] | |||

| Currency | Euro (€)2 (EUR) |

|||

| Time zone | WET (UTC+0) | |||

| - | Summer (DST) | WEST (UTC+1) | ||

| Internet TLD | .pt | |||

| Calling code | [[+351]] | |||

| 1 | Mirandese, spoken in some villages of the municipality of Miranda do Douro, was officially recognized in 1999 (Lei n.° 7/99 de 29 de Janeiro), since then awarding an official right-of-use Mirandese to the linguistic minority it is concerned.[6] The Portuguese Sign Language is also recognized. | |||

| 2 | Before 1999: Portuguese escudo. | |||

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country in southwestern Europe, on the Iberian Peninsula.

The land within the borders of today's Portuguese Republic has been constantly settled since Prehistoric Iberia|prehistoric times.

During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, with its global empire which included possessions in Africa, Asia and South America, Portugal was one of the world's major economic, political, and cultural powers. In the nineteenth century, armed conflict with French and Spanish invading forces, and the loss of its largest territorial possession abroad, Brazil, which declared independence unilaterally, disrupted political stability and potential economic growth.

The Carnation Revolution's coup d'état in 1974, replaced an authoritarian dictatorship with a communist state, while the country granted independence to its overseas territories in Africa.

Portugal is a developed country, and although having the lowest GDP per capita of all Western European countries, it has a high Human Development Index and one of the highest quality of life ratings in the world.

Geography

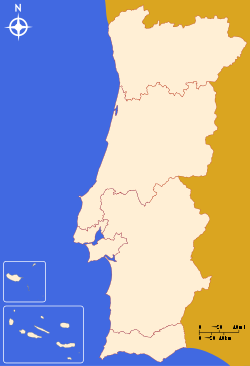

Being the westernmost country of mainland Europe, Portugal is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the west and south and by Spain to the north and east. The Atlantic archipelagos of the Azores and Madeira are also part of Portugal.

Portugal's total land area is 35,580 square miles (92,345 square kilometers) or slightly smaller than Indiana in the United States. Mainland Portugal is split by its main river, the Tagus. The northern landscape comprises the mountainous border of the Meseta, the ancient rock core of the Iberian Peninsula, with plateaus indented by river valleys. The south, between the Tagus and the Algarve (the Alentejo), features mostly rolling plains.

The country's highest point is Mount Pico on Pico Island, an ancient volcano measuring 7713 feet (2351 meters). Mainland Portugal's highest point is Serra da Estrela, measuring 6558 feet (1993 meters).

The climate can be classified as Oceanic in the north and Mediterranean in the south. Portugal is one of the warmest European countries, the annual temperature averages on the mainland are 55°F (13°C) in the north and 64°F (18°C) in the south. The Madeira and Azores Atlantic archipelagos have a narrower temperature range. Generally, spring and summer are sunny, whereas autumn and winter are rainy and windy. Extreme temperatures occur in northeastern parts of the country in winter (where they may fall to 3°F or -16°C) and south-eastern parts in summer (where they can soar up to 114°F or 46°C). Sea coastal areas are milder, temperatures varying between -2°C in the coldest winter mornings and 37°C in the hottest summer afternoons. Absolute extremes registered so far have been -23°C in Serra da Estrela and 48°C in the Alentejo region.

The south has a climate somewhat warmer and drier than in the cooler and rainier north. The Algarve, separated from the Alentejo by mountains, enjoys a Mediterranean climate much like southern Spain. Snow falls occasionally (on some cold winter days) in the northern interior from October to May, although it is rare in the south. The coast registers snow usually once in five or six years.

Portugal's major rivers, the Douro, Tagus (Rio Tejo), and Guadiana, flow from the central Meseta before draining west to the Atlantic. The Guadiana flows south.

The plants and animals of Portugal are a mixture of Atlantic, or European, and Mediterranean (with some African) species. North of the Mondego valley, 57 percent of the plants are European species (more than 86 percent in the northern interior), and only 26 percent Mediterranean; in the south the proportions are 29 and 46 percent, respectively.

As in Spain, the wild goat, wild pig and deer are found in the Portuguese countryside. The wolf survives in the remote parts of Serra da Estrela, the lynx in Alentejo, while the fox, rabbit and Iberian hare are everywhere. Birds abound because the peninsula lies on the winter migration route of European species. Fish are plentiful, especially the European sardine, and crustaceans are common on the northern rocky coasts.

Natural resources include fish, forests (cork), iron ore, copper, zinc, tin, tungsten, silver, gold, uranium, marble, clay, gypsum, salt, arable land, and hydropower.

Portugal's Exclusive Economic Zone, a seazone over which the Portuguese have special rights over the exploration and use of marine resources, has 1,727,408 km². This is the 3rd largest Exclusive Economic Zone of the European Union and the eleventh in the world.

Conservation areas of Portugal include one national park (Parque Nacional), 12 natural parks (Parque Natural), nine natural reserves (Reserva Natural), five natural monuments (Monumento Natural), and seven protected landscapes (Paisagem Protegida), ranging from the Parque Nacional da Peneda-Gerês to the Parque Natural da Serra da Estrela to the Paul de Arzila.

Lisbon is the capital and largest city of Portugal. Its municipality, which matches the city proper excluding the larger continuous conurbation, has a municipal population of 564,477, although the Lisbon Metropolitan Area in total has around 2.8 million inhabitants, and 3.34 million people live in the broader agglomeration of Lisbon Metropolitan Region (includes cities ranging from Leiria to Setúbal). Other metropolitan areas are Porto, Braga, Coimbra, Setúbal, and Aveiro.

History

Pre-history

The Iberian Peninsula, comprising modern Spain and Portugal, has been inhabited by hominin species for at least half a million years. Neanderthal bones, the earliest human remains found in Portugal, were discovered in Furninhas, and Paleolithic art has been found in the Valley of Foz Côa. Cro-Magnons began arriving in the Iberian Peninsula from the Pyrenees some 35,000 years ago. Mesolithic middens found in the lower Tagus valley indicate a distinct culture that existed about 5500 B.C.E. Neolithic people migrated from Andalusia, leaving remains of beehive huts and passage graves.

Celtic societies

Early in the first millennium B.C.E., several waves of Celts invaded Portugal from central Europe and intermarried with the local Iberian people, forming the Celtiberian ethnic group, with many tribes. Chief among these tribes were the Lusitanians, the Calaicians or Gallaeci and the Cynetes or Conii; among the lesser tribes were the Bracari, Celtici, Coelerni, Equaesi, Grovii, Interamici, Leuni, Luanqui, Limici, Narbasi, Nemetati, Paesuri, Quaquerni, Seurbi, Tamagani, Tapoli, Turduli, Turduli Veteres, Turdulorum Oppida, Turodi, and Zoelae). By 500 B.C.E., Iron Age cultures predominated in the north, while there were some small, semipermanent commercial coastal settlements founded by the Greeks and, in the Algarve, Tavira founded by Phoenicians-Carthaginians.

Roman Lusitania and Galicia

The first Roman invasion of the Iberian Peninsula occurred in the Second Punic War (218–201 B.C.E.), against the Carthaginians, who were expelled from their coastal colonies. The conquest started from the south, where the Romans found friendly natives, the Conii, and took several decades. Celtic peoples and others occupied the west. Within 200 years, almost the entire peninsula had been annexed to the Roman Empire. The Romans burdened the native tribes with heavy taxes, and suffered a severe setback in 194 B.C.E., when the Lusitanians and other tribes, under the leadership of Viriathus (known as Viriato in Portuguese, wrested control of all of Portugal. Rome sent numerous legions and its best generals to quell the rebellion, but to no avail. The Roman leaders bribed Viriathus's ambassador to kill his own leader, and once Viriathus was assassinated, the resistance was soon over. Rome installed a colonial regime. During this period, Lusitania grew in prosperity and many of modern day Portugal's cities and towns were founded, although Lisbon already existed. In 27 B.C.E., Lusitania gained the status of Roman province. Later, a northern province of Lusitania was formed, known as Gallaecia, with capital in Bracara (today's Braga). Around 250 C.E., Braga became an Episcopal Diocese.

Germanic kingdoms

After 406 C.E., Germanic tribes, namely the Suevi, the Vandals (Silingi and Hasdingi) and their allies, the Sarmatian Alans, invaded the peninsula. Only the kingdom of the Suevi (Quadi and Marcomanni) would endure after the arrival of another wave of Germanic invaders, the Visigoths, who conquered all of the Iberian Peninsula by 584–585. The Germanic tribe of the Buri, who accompanied the Suevi in their invasion, settled in the region between the rivers Cávado and Homem, in the area known as thereafter as Terras de Boiro (Lands of the Buri).

Muslim conquest

The next wave of invaders were Berber Muslims, from North Africa, led by Tariq ibn Ziyad, who conquered nearly all the Iberian Peninsula from 711–718 C.E. The Muslims continued north until they were defeated in central France at the Battle of Tours in 732. Astonishingly, the invasion began with an invitation from a Visigoth faction within Spain for support. The Roman Catholic populace, unimpressed with the constant internal feuding of the Visigothic leaders, often stood apart from the fighting, often welcoming the new rulers, known as Moors (Mouros), thereby forging the basis of the distinctly Spanish-Muslim culture of Al-Andalus, the Arabic name given to those parts of the Iberian Peninsula governed by Muslims between 711 and 1492. Only three small counties in the mountains of the north of Spain managed to cling to their independence: Asturias, Navarra and Aragon, which eventually became kingdoms.

'Abd al-Rahman I set up the Umayyad monarchy at Córdoba in 756. The Muslim emirate proved strong in its first three centuries; stopping Charlemagne's massive forces at Saragossa and, after a serious Viking attack, established effective defenses. Christian Spain struck back from mountain redoubts by seizing the lands north of the Duero river. The Franks were able to seize Barcelona (801), and the Spanish Marches). Otherwise, the Christians were unable to make headway against the superior forces of Al-Andalus for several centuries.

The Reconquista

In 868, Count Vímara Peres reconquered and governed the region between the Minho and Douro rivers. A dependency of the Kingdom of León in the northwest Iberia, Portucale occasionally gained de facto independence during weak Leonese reigns. In 997, Bermudo II (956-999) King of León, controlled Portucale, and in 1064, Ferdinand I, King of Castile and León, completed the reconquest south to Coimbra. The reconquered districts were organized into a feudal county comprised of Spanish fiefs. The name Portugal derived from the northernmost fief, the Comitatus Portaculenis, around the old Roman port of Portus Cale (present-day Porto). Portugal gained its first independence (as the Kingdom of Galicia and Portugal) in 1065 under the rule of Garcia II. Due to feudal power struggles, Portuguese and Galician nobles rebelled. In 1072, the country rejoined León and Castile under Garcia II's brother Alphonso VI of Castile.

Portugal separates from Galicia

In 1095, Portugal separated almost completely from the Kingdom of Galicia. Its territories consisting largely of mountain, moorland and forest were bounded on the north by the Minho, on the south by the Mondego. Towards the close of the eleventh century, crusading knights came from every part of Europe to aid the kings of León, Castile and Aragon in combating the Moors. The Burgundian knight Henry (1066-1112) became count of Portugal and defended his independence, merging the County of Portucale and the County of Coimbra. Henry declared independence for Portugal while a civil war raged between Leon and Castile, but died without achieving it. His son, Afonso Henriques (1109-1185), took control of the country.

Medieval kingdom

Portugal traces its origin as a nation to June 24, 1128, with the Battle of São Mamede, when Afonso defeated his mother, Countess Teresa, and her lover, Fernão Peres de Trava, in battle, thereby establishing himself as sole leader. He proclaimed himself Prince of Portugal and in 1139 the first King of Portugal. A victory over the Muslims at Ourique in 1139 is taken as the point when Portugal transformed from a county into an independent kingdom, although it was not until 1143 that the Holy See formally recognized Portugal as independent, and in 1179, the Pope declared Afonso I as king. Afonso first ruled from Guimarães, then from Coimbra.

South Portugal reconquered

From 1249 to 1250, Afonso Henriques and his successors, aided by military monastic orders, re-conquered the Algarve, the southernmost region, from the Moors. In 1255, the capital shifted to Lisbon. Portugal's land-based boundaries have been notably stable in history. The border with Spain has remained almost unchanged since the thirteenth century. The Treaty of Windsor (1386) created an alliance between Portugal and England that remains in effect to this day.

In 1383, the king of Castile, husband of the daughter of the Portuguese king who had died without a male heir, claimed his throne. An ensuing popular revolt led to the 1383-1385 Crisis. A faction of petty noblemen and commoners, led by John of Aviz (later John I), seconded by General Nuno Álvares Pereira defeated the Castilians in the Battle of Aljubarrota.

Since early times, fishing and overseas commerce have been the main economic activities. Henry the Navigator's interest in exploration together with some technological developments in navigation made Portugal's expansion possible and led to great advances in geographic, mathematical, scientific knowledge and technology, more specifically naval technology.

Portuguese expansion

In the following decades, Portugal spearheaded the exploration of the world and undertook the Age of Discovery. Prince Henry the Navigator, son of King João I, became the main sponsor and patron of this endeavor. In 1415, Portugal gained the first of its overseas colonies when a fleet conquered Ceuta, a prosperous Islamic trade center in North Africa. There followed the first discoveries in the Atlantic: Madeira and the Azores, which led to the first colonization movements. Throughout the fifteenth century, Portuguese explorers sailed the coast of Africa, establishing trading posts for slaves and gold as they looked for a route to India and its spices, which were coveted in Europe. The Treaty of Tordesillas, signed with Spain in 1494, divided the (largely undiscovered) world equally between the Spanish and the Portuguese, along a north-south meridian line 370 leagues (1770 km/1100 miles) west of the Cape Verde islands, with all lands to the east belonging to Portugal and all lands to the west to Spain. In 1498, Vasco da Gama finally reached India and brought economic prosperity to Portugal and its then population of one million residents. In 1500, Pedro Álvares Cabral, en route to India, discovered Brazil and claimed it for Portugal. Ten years later, Afonso de Albuquerque conquered Goa, in India, Ormuz in the Persian Strait, and Malacca in what is now a state in Malaysia. Thus, the Portuguese empire held dominion over commerce in the Indian Ocean and South Atlantic. It may also have been Portuguese sailors that were the first Europeans to discover Australia.

Spain invades

In 1578, a very young king Sebastian died in battle without an heir (the body was not found), leading to a dynastic crisis. The Cardinal Henry became ruler, but died two years after. Portugal was worried about the maintenance of its independence and sought help to find a new king. Because Philip II of Spain was the son of a Portuguese princess, Spain invaded Portugal and the Spanish ruler became Philip I of Portugal in 1580; the Spanish and Portuguese Empires were under a single rule. Impostors claimed to be King Sebastian in 1584, 1585, 1595 and 1598. "Sebastianism," the myth that the young king will return to Portugal on a foggy day has prevailed until modern times. After the sixteenth century, Portugal's wealth decreased as Portuguese colonies were attacked by Spain's opponents, especially the Dutch and English.

Portuguese nobles rebel

Life was calm under the first two Spanish kings, who maintained Portugal's status, gave excellent positions to Portuguese nobles in the Spanish courts, and Portugal maintained an independent law, currency and government. But Philip III (1605-1665) tried to make Portugal a Spanish province, and Portuguese nobles lost power. In 1640, John IV (1603-1656) spearheaded an uprising backed by disgruntled nobles and was proclaimed king on December 1, 1640. This was the beginning of the House of Braganza, which was to reign until 1910. In the seventeenth century, the Portuguese emigrated in large numbers to Brazil. By 1709, John V prohibited emigration, since Portugal had lost a sizable fraction of its population. Brazil was elevated to a vice-kingdom and Amerindians gained total freedom.

The Pomballine era

During the reign of Joseph Emanuel (1750-1777), the Chief-Minister, Sebastião de Melo, the talented son of a Lisbon squire, was made prime minister in 1755. Impressed by British economic success he had witnessed while ambassador, he successfully implemented similar economic policies in Portugal. He abolished slavery in the Portuguese colonies in India, reorganized the army and the navy, restructured the University of Coimbra, and ended discrimination against different Christian sects in Portugal. Sebastião de Melo's greatest reforms were economic and financial, with the creation of several companies and guilds to regulate every commercial activity. He demarcated the region for production of port to ensure the wine's quality, and his was the first attempt to control wine quality and production in Europe. He imposed strict law upon all classes of Portuguese society from the high nobility to the poorest working class, along with a widespread review of the country's tax system. These reforms gained him enemies in the upper classes, especially among the high nobility, who despised him as a social upstart.

Lisbon earthquake

Disaster fell upon Portugal in the morning of November 1, 1755, when Lisbon was struck by a violent earthquake with an estimated Richter scale magnitude of 9. The earthquake, the subsequent tsunami, and ensuing fires, killed between 60,000 and 90,000 people and destroyed 85 percent of the city. Sebastião de Melo survived by a stroke of luck and then immediately embarked on rebuilding the city, with his famous quote: What now? We bury the dead and feed the living. Despite the calamity, Lisbon suffered no epidemics and within less than one year was already being rebuilt. The new downtown of Lisbon was designed to resist subsequent earthquakes. Architectural models were built for tests, and the effects of an earthquake were simulated by marching troops around the models. The buildings and big squares of the Pombaline Downtown of Lisbon still remain as one of Lisbon's tourist attractions: They represent the world's first quake-proof buildings. Sebastião de Melo also made an important contribution to the study of seismology by designing an inquiry that was sent to every parish in the country.

The Tavore affair

Following the earthquake, Joseph I gave his prime minister even more power, and Sebastião de Melo became a powerful, progressive dictator. As his power grew, his enemies increased in number, and bitter disputes with the high nobility became frequent. In 1758, Joseph I was wounded in an attempted assassination. The Tavora family and the Duke of Aveiro were implicated and executed after a quick trial. The Jesuits were expelled from the country and their assets confiscated. Sebastião de Melo showed no mercy and prosecuted every person involved, even women and children. This was the final stroke that broke the power of the aristocracy and ensured the victory of the Minister against his enemies. Based upon his swift resolve, Joseph I made his loyal minister Count of Oeiras in 1759. Made Marquis of Pombal in 1770, de Melo effectively ruled Portugal until Joseph I's death in 1779. His successor, the ultra-religious and melancholic Queen Maria I of Portugal (1734-1816), disliked the Marquis, dismissed the marquis as a result of his anti-aristocrat and anti-Jesuit policies.

Napoleonic Wars

In 1807, Portugal refused Napoleon's demand to join an embargo against the United Kingdom. A French invasion under General Junot followed, and Lisbon was captured on December 1, 1807. British intervention in the Peninsular War restored Portuguese independence, the last French troops being expelled in 1812. The war cost Portugal the province of Olivença, now governed by Spain. Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, was the Portuguese capital between 1808 and 1821.

Constitutional monarchy

The Portuguese army led a movement to bring about a constitutional government, with insurrections in 1820 at Oporto on August 24, and Lisbon on September 15. King John VI of Portugal (1767-1826), agreed to return from Brazil to Portugal as constitutional monarch, making his son, Dom Pedro, regent of Brazil. Brazil declared its independence from Portugal in 1822, and Pedro was made constitutional emperor Pedro I of that country. Lisbon regained its status as the capital of Portugal. In Portugal, Pedro’s brother, Dom Miguel, led an insurrection on April 30, 1824, to overthrow the constitutionalists. John VI remained in power, and Miguel went into exile in Vienna.

The death of John VI in 1826 led to a crisis of royal succession. His eldest son, Pedro I of Brazil became Pedro IV of Portugal, and put into effect a parliamentary regime which established four branches of government. The legislature was divided into two chambers. The upper chamber, the Chamber of Peers, was composed of life and hereditary peers and clergy appointed by the king. The lower chamber, the Chamber of Deputies, was composed of 111 deputies elected to four-year terms by the indirect vote of local assemblies, which in turn were elected by a limited suffrage of male tax-paying property owners. Judicial power was exercised by the courts; executive power by the ministers of the government; and moderative power by the king, who held an absolute veto over all legislation.

But neither the Portuguese nor the Brazilians wanted a unified monarchy, so Pedro IV abdicated the Portuguese crown in favor of his seven-year-old daughter, Maria da Glória, on the condition that when of age she marry his brother, Miguel. Dissatisfaction at Pedro's constitutional reforms led the "absolutist" faction of landowners and the church to proclaim Miguel as king in February 1828. Miguel dissolved the Chamber of Deputies and the Chamber of Peers and, in May, summoned the traditional cortes of the three estates of the realm to proclaim his accession to absolute power. The Cortes of 1828 assented to Miguel's wish, proclaimed him king as Miguel I of Portugal and nullified the Constitutional Charter.

The Liberal Wars

The Liberal Wars, also known as the Portuguese Civil War, was a war between progressive constitutionalists and authoritarian absolutists in Portugal over royal succession that lasted from 1828 to 1834, and involved the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, France, Portugal, Portuguese rebels, the bishops of the Roman Catholic Church, and Spain. Revolution had swept away absolutist monarchy in France in 1789, and the absolutist party of landowners and the Church in Portugal, were emboldened by the fact that restoration of the autocratic Ferdinand VII in Spain (1823) meant Napoleonic reforms were being dismantled there. As rebellion against the absolutist Miguel spread in Portugal, thousands of liberals were either arrested or fled to Spain and Britain, and there followed five years of repression before Pedro, with British assistance, eventually forced Miguel to abdicate and go into exile in 1834, and placed his daughter on throne as Queen Maria II (1819-1853). Conflict continued during her reign between authoritarian absolutists, who supported the 1822 constitution, opposed the progressive constitutionalists, who supported the 1826 charter. Strife diminished under her successors Pedro V, who reigned from 1853 to 1861, and Louis, who reigned from 1861 to 1889.

Expansion in Africa

At the height of European colonialism in the nineteenth century, Portugal had lost its territory in South America and all but a few bases in Asia. During this phase, Portuguese colonialism focused on expanding its outposts in Africa into nation-sized territories to compete with other European powers there. Portuguese territories eventually included the modern nations of Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe, Guinea-Bissau, Angola, and Mozambique.

King Carlos and son murdered

Opposition grew during the reign of Carlos I (1863-1908), who was despised for corruption, and further hated for the appointment in 1906 of the authoritarian João Franco (1855–1929) as prime minister. On February 1, 1908, republican activist Alfredo Costa shot dead King Carlos I of Portugal, while another assassin shot eldest son Prince Luís Filipe, who later died. Soon after, the second son of Carlos ascended the throne as Manuel II (1889-1932), and restored constitutional government, although he too became hated for corruption. Franco was forced out of power on February 4 and went into exile.

1910 revolution

New elections were held, but factionalism prevented the formation of a stable government. On October 1, 1910, a visit by president Hermes da Fonseca of Brazil provided a pretext for extensive republican demonstrations. On October 3, the Army refused to put down a mutiny on Portuguese warships anchored in the estuary of the Tagus River, and instead took up positions around Lisbon. On October 4, two of the warships began to shell the royal palace, causing Manuel II and the royal family to flee to Britain. On October 5, a provisional republican government was organized with the writer Teófilo Braga as President.

First republic

The Portuguese First Republic spans a complex 16-year period in the history of Portugal, between the end of the Constitutional Monarchy marked by the October 5th revolution of 1910, and the coup d'état on May 28, 1926. A republican Constitution was approved in 1911, inaugurating a parliamentary regime with reduced presidential powers and two chambers of parliament. The republic fractured Portuguese society. Even the Portuguese Republican Party]] (PRP) had to endure the secession of its more moderate elements, who formed conservative republican parties like the Evolutionist Party and the Republican Union. In spite of these splits the PRP, led by Afonso Costa (1871-1937), preserved its dominance. A number of opposition forces resorted to violence.

World War I

World War I was a global military conflict which took place primarily in Europe from 1914 to 1918. Over 40 million casualties resulted, including approximately 20 million military and civilian deaths. Early in 1916, honoring its alliance with Britain, Portugal seized German ships in the Lisbon harbor. Germany declared war on Portugal. Portuguese troops fought in France and in Africa. However, Portugal's involvement in the First World War further deepened existing political and ideological fractures. Two dictatorships resulted, the first led by General Pimenta de Castro (January-May 1915), and the second by Sidónio Pais (December 1917-December 1918).

Sidónio Pais (1872-1918) sought to rescue traditional values, notably the Pátria (Homeland), and attempted to rule in a charismatic fashion. He moved to abolish traditional political parties, and to alter the existing mode of national representation in parliament through the creation of a corporative Senate, to found a single party (the National Republican Party), and give mobilizing power to the leader. The state became economically interventionist, while repressing working-class movements and leftist republicans. Sidónio Pais also attempted to restore public order and to make the Republic more acceptable to monarchists and Catholics. He escaped a first assassination attempt, but was shot on December 14, 1918.

Monarchist uprising

The vacuum of power created by Sidónio Pais' assassination led the country to a brief civil war. The monarchy’s restoration was proclaimed in the north of Portugal on January 19, 1919, and, four days later, a monarchist insurrection broke out in Lisbon. A republican coalition government, led by José Relvas (1858-1929), coordinated the struggle against the monarchists by loyal army units and armed civilians. After a series of clashes the monarchists were definitively chased from Oporto on February 13, 1919. This military victory allowed the Portuguese Republican Party to return to government and to emerge triumphant from the elections held later that year, having won the usual absolute majority.

Republic restored

In August 1919, a conservative president was elected – António José de Almeida – and his office was given the power to dissolve parliament. Relations with the Holy See, restored by Sidónio Pais, were preserved. The president in May 1921 named a Liberal government to prepare the forthcoming elections. These were held on July 10, 1921, with victory going to the party in power. However, Liberal government did not last long. On October 19, a military coup was carried out during which a number of prominent conservative figures, including Prime Minister António Granjo, were assassinated. Between 1910 and 1926 there were 45 governments. Many different formulas were attempted, including single-party governments, coalitions, and presidential executives, but none succeeded.

Second Republic, the Salazar regime

By the mid-1920s, authoritarian governments gained popularity. Since the opposition's constitutional route to power was blocked by the Portuguese Republican Party to protect itself, it turned to the army for support, and a coup d'état was carried out on May 28, 1926. The military leaders selected General António de Fragoso Carmona (1869-1951) to head the new government. In 1928 Carmona was elected president, and he appointed António de Oliveira Salazar (1889-1970), a professor of economics, as Minister of Finance. Salazar was given wide powers to put Portuguese finances on a sound basis, and soon became the most powerful political figure in Portugal. He restored much of the power of the Church, founded the authoritarian National Union political organization, became prime minister in 1932, influenced a new constitution in 1933, and ruled Portugal to 1968.

The Estado Novo (New State), also known as the Second Republic, was a dictatorial regime which differed from the fascist regime of Italy by its more moderate use of state violence. Salazar was a Catholic traditionalist who believed in the necessity of control over the forces of economic modernization in order to defend the religious and rural values of the country, which he perceived as being threatened. One of the pillars of the regime was the PIDE, the secret police. Many political dissidents were imprisoned at the Tarrafal prison in the African archipelago of Cape Verde, on the capital island of Santiago, or in local jails. Strict state censorship was in place.

The whole education system was focused toward the exaltation of the Portuguese Nation and its overseas colonies (the Ultramar). The motto of the regime was Deus, Pátria e Familia (meaning God, Fatherland and Family). The Estado Novo accepted the idea of corporatism as an economic model. Corporatism is a political or economic system under which government was to be formed of economic entities organized according to their function, rather than by individual representation. Employers were to form one group, labor another, and they and other groups were to deal with one another through their representative organizations. This policy was pursued in order to protect the elites and defend oligarchic capitalism as the economic system, under state paternalist supervision. Although Salazar refused to sign the Anti-Comintern Pact in 1938, the Portuguese Communist Party was intensely persecuted. So were anarchists, liberals, republicans and anyone opposed to the regime. Salazar supported General Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939).

World War II

World War II, from 1939 to 1945, was a worldwide military conflict; the amalgamation of two separate conflicts, one beginning in Asia in 1937 as the Second Sino-Japanese War, and the other beginning in Europe in 1939 with the invasion of Poland. This global conflict split a majority of the world's nations into two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis, and resulted in the deaths of over 70 million people, making it the deadliest conflict in human history. In 1939, Portugal signed a non-aggression pact with Spain, and added on July 29, 1940, a neutrality protocol for both countries. In October 1943, Portugal allowed the Allies to base aircraft and ships in the Azores. The war upset the planned economy, the fishing industry declined, exports lessened, and refugees crowded the country. The Japanese threatened Portuguese territories in Asia, and Timor was captured in 1942.

Post-war Portugal

Economic conditions improved slightly in the 1950s, when Salazar instituted the first of two five-year economic plans. These plans stimulated some growth, and living standards began to rise. Portugal's economy benefited from increased raw material exports to the war-ravaged and recovering nations of Europe. A new road system was built, new bridges spanned the rivers and the Educational Program was able to build a primary school in each Portuguese town. Further education was discouraged except for a tiny elite, and was closely supervised. Salazar believed that education destroyed the basic conservative and religious values of the people and should only be accessible to a minority with close ties to the regime.

Crisis years

The 1960s, however, were crisis years for Portugal. With the economic recovery of Europe in the 1960s, the Portuguese economy stagnated. Liberal economic reforms advocated by some of the elements of the ruling party, which were successfully implemented in neighboring Spain, were rejected out of fear that industrialization would strengthen the Communists and other left-wing movements.

In 1962, the "Academic Crisis" occurred. The regime, fearing the growing popularity of democratic ideas among the students, closed several student associations and organizations, including the important National Secretariat of Portuguese Students. The students, with strong support from the Portuguese Communist Party, responded with demonstrations. These culminated on March 24 with a huge student demonstration in Lisbon that was brutally suppressed by the shock police, leaving hundreds of students injured. The students began a strike that marked a significant point in the resistance against the regime.

The economic dead-end forced hundreds of thousands of Portuguese workers each year to seek better economic and political conditions in other countries, or to escape conscription. Over 15 years, nearly one million emigrated to France, another million to the United States, many hundreds of thousands to Germany, Switzerland, the UK, Luxembourg, Venezuela or Brazil. Political parties, such as the Socialist Party, persecuted at home, were established in exile. The only party which managed to continue (illegally) operating in Portugal during all the dictatorship was the Portuguese Communist Party.

Uprisings in colonies

The end of the Estado Novo began with the uprisings in the colonies in the 1960s. In December 1961, the Portuguese army was defeated in armed action in its colony of Portuguese India against an Indian invasion, resulting in the loss of the Portuguese territories there. The Independence Movements in Angola, Mozambique and Guinea were supported by both the USA and the USSR, which both wanted to end all colonial empires and expand their own spheres of influence. The colonial wars had the same effects in Portugal as the Vietnam War in the United States: they were unpopular, messy and ultimately lost, killing many thousands, and struck at the ideological foundation of the regime. Although Portugal was able to maintain some superiority in the colonies by its use of elite paratroopers and special operations troops, the foreign support to the guerrillas made them more maneuverable, allowing them to inflict heavy losses on the Portuguese army.

Salazar dies

Salazar, the strong man of the regime, died in 1970. His replacement was one of his closest advisors, Marcelo Caetano (1906-1980), a law professor and businessman and a long-time associate of Salazar. Caetano had been prime minister since September 1968, when Salazar was incapacitated by a stroke. Caetano offered hope that the regime would open up, however the colonial wars in Africa continued, political prisoners remained incarcerated, freedom of association was not restored, censorship was only slightly eased and the elections remained tightly controlled. The regime retained its characteristic traits: censorship, a corporative economy dominated by a handful of groups, continuous surveillance and intimidation of all sectors of society through the use of a political police, and techniques instilling fear, such as arbitrary imprisonment, systematic political persecution, and assassination.

Spinola and the Carnation Revolution

The Carnation Revolution was an almost bloodless, leftist, military-led coup d'état that started in April 1974, in Lisbon, and effectively changed the Portuguese regime from an authoritarian dictatorship to a communist state. On April 25, 1974, a group of younger officers belonging to an underground organization, the Armed Forces Movement (Movimento das Forças Armadas—MFA), overthrew the Caetano regime, and General António de Spínola (1910-1996) emerged as the titular head of the new government. Caetano and other high-ranking officials of the old regime were arrested and exiled, many to Brazil. The coup released long pent-up frustrations when thousands, and then tens of thousands, of Portuguese poured into the streets celebrating the downfall of the regime and demanding further change. The coercive apparatus of the dictatorship—secret police, Republican Guard, official party, censorship—was overwhelmed and abolished. Workers began taking over shops from owners, peasants seized private lands, low-level employees took over hospitals from doctors and administrators, and government offices were occupied by workers who sacked the old management.

The demonstrations began to be manipulated by organized political elements, principally the Portuguese Communist Party and other groups farther to the left. Radical labor and peasant leaders emerged from the underground where they had been operating for many years. Mário Soares, the leader of the Socialist Party of Portugal and Álvaro Cunhal, head of the Portuguese Communist Party returned from exile to Portugal within days of the revolt and received heroes' welcomes.

Spínola became the first interim president of the new regime in May 1974, and he chose the first of six provisional governments that were to govern the country until two years later when the first constitutional government was formed. The fourth provisional government, headed by General Vasco Gonçalves, with eight military officers and members of the Socialist Party, Portuguese Communist Party, Social Democratic Party, and Portuguese Democratic Movement, a party close to the Communist Party, began a wave of nationalizations of banks and large businesses. Because the banks were often holding companies, the government came after a time to own almost all the country's newspapers, insurance companies, hotels, construction companies and many other kinds of businesses, so that its share of the country's gross national product amounted to 70 percent.

Empire ends

In 1974 and 1975, Portugal granted independence to its overseas provinces in Africa (Mozambique, Angola, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde and São Tomé and Príncipe). In that same year, Indonesia invaded and annexed the Portuguese province of Portuguese Timor (East Timor) in Asia before independence could be granted. The return of troops and European settlers to Portugal from the newly independent nations added to Portugal’s problems of unemployment and political unrest. With the independence of its colonies, the 560-year-old Portuguese Empire had in effect ended, although Macau was still under Portuguese administration.

The transfer of the sovereignty of Macau to China on December 20, 1999, under the terms of an agreement negotiated between People's Republic of China and Portugal twelve years earlier, marked the final end of the Portuguese overseas empire.

Constitutional government

Elections were held on April 25, 1975, for the Constituent Assembly to draft a constitution. The Socialist Party won nearly 38 percent the vote, while the Social Democratic Party took 26.4 percent. The Portuguese Communist Party, which opposed the elections because its leadership expected to do poorly, won less than 13 percent of the vote. There followed the "hot summer" of 1975, when the revolution made itself felt in the countryside. Landless agricultural laborers in the south seized the large farms on which they worked. The United States and many West European countries expressed considerable alarm at the prospect of a Marxist-Leninist takeover in a NATO country. An attempted coup by radical military units in November 1975 marked the last serious leftist effort to seize power.

A constitution, which pledged the country to realize socialism and declared the extensive nationalizations and land seizures of 1975 irreversible, was proclaimed on April 2, 1976. Several weeks later, on April 25, elections for the new parliament, the Assembly of the Republic, were held. Moderate democratic parties received most of the vote. Revolutionary achievements were not discarded, however. Elections for the presidency were held in June and won easily by General António Ramalho Eanes, who enjoyed the backing of parties to the right of the communists, the Socialist Party, the Social Democratic party, and the Democratic and Social Centre/People's Party.

Although the Socialist Party did not have a majority in the Assembly of the Republic, Eanes allowed it to form the first constitutional government with Mario Soares as prime minister. It governed from July 23, 1976, to January 30, 1978. A second government, formed from a coalition with the Democratic and Social Centre/People's Party, lasted from January to August of 1978 and was also led by Soares. The Socialist Party governments faced enormous economic and social problems such as runaway inflation, high unemployment, falling wages, and an enormous influx of Portuguese settlers from Africa. Failure to fix the economy, even after adopting a painful austerity program imposed by the International Monetary Fund , ultimately forced the PS to relinquish power.

President Eanes formed a number of caretaker governments in the hope that they would rule until the parliamentary elections mandated by the constitution could be held in 1980. There were, therefore, three short-lived governments appointed by President Eanes. These were led by Prime Minister Alfredo Nobre da Costa from August 28, to November 21, 1978; Carlos Mota Pinto from November 21, 1978, to July 31, 1979; and Maria de Lourdes Pintasilgo (Portugal's first woman prime minister) from July 31, 1979, to January 3, 1980.

Francisco Sá Carneiro of the Social Democrat Party became prime minister in January 1980, and the tenor of parliamentary politics moved to the right as the government attempted to undo some of the revolution's radical reforms. The powers conferred on the presidency by the constitution of 1976 enabled President Eanes to block the centrist economic policies of the Democratic Alliance (a coalition of the Social Democrat Party and Democratic Social Centre party). For this reason, the Democratic Alliance concentrated on winning enough seats in the October 1980 elections to reach a two-thirds majority to effect constitutional change and on electing someone other than Eanes in the presidential elections of December 1980.

Since 1986

In 1986, Portugal entered the European Economic Community and joined the Euro in 1999. The Asian dependency of Macao, after an agreement in 1986, was returned to Chinese sovereignty in 1999. Portugal applied international pressure to secure East Timor's independence from Indonesia, as East Timor was still legally a Portuguese dependency, and recognized as such by the United Nations. After a referendum in 1999, East Timor voted for independence and Portugal recognized its independence in 2002.

Government and politics

Constitutional structure

Portugal is a parliamentary representative democratic republic, as defined by the constitution of 1976, with separation of powers among legislative, executive, and judicial branches. The president, who is chief of state and is directly elected to a five-year term, appoints the prime minister and council of ministers, according to assembly election results. There is also a council of state, which is a presidential advisory body composed of six senior civilian officers. The unicameral assembly of the republic (Assembleia da Republica) has 230 members who are elected by popular vote to serve four-year terms. Following legislative elections, the leader of the majority party or majority coalition is usually appointed prime minister by the president. Suffrage is universal to those aged 18 years of age and over.

Portugal uses the civil law legal system, also called the continental family legal system. Until the end of the nineteenth century, French law was the main influence. Since then the major influence has been German law. The Constitutional Tribunal reviews the constitutionality of legislation. Portugal accepts compulsory International Court of Justice jurisdiction with reservations.

The national and regional governments, and the Portuguese parliament, are dominated by two political parties, the Socialist Party and the Social Democratic Party. Minority parties CDU (Portuguese Communist Party plus Ecologist Party "The Greens"), Bloco de Esquerda (Left Bloc) and CDS-PP (People's Party) are also represented in the parliament and local governments.

Foreign relations

The foreign relations of Portugal are linked with its historical role as a key player in the Age of Discovery and the holder of the now defunct Portuguese Empire. It is a member of the European Union (since 1986) and the United Nations (since 1955); as well as a founding member of the European Union's Eurozone, OECD, NATO, and CPLP (Comunidade dos Países de Língua Portuguesa—Community of Portuguese Language Countries). The only international dispute concerns the municipality of Olivença (Olivenza in Spanish). Under Portuguese sovereignty since 1297, the municipality of Olivença was ceded to Spain under the Treaty of Badajoz in 1801, after the War of the Oranges. Portugal claimed it back in 1815 under the Treaty of Vienna. Nevertheless, bilateral diplomatic relations between the two neighboring countries are cordial, as well as within the European Union.

Military of Portugal

The armed forces have three branches: Army, Navy, and Air Force. The military of Portugal serves primarily as a self-defense force, and providing humanitarian assistance. Since the early 2000s, compulsory military service is no longer practiced. The age for voluntary recruitment is set at 18. In the twentieth century, Portugal engaged in two major military interventions: the First Great War and the Colonial War (1961-1974). Portugal has participated in peacekeeping missions in East Timor, Bosnia, Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq (Nasiriyah), and Lebanon.

Administrative divisions

Portugal has an administrative structure of 308 municipalities (Portuguese singular/plural: concelho/concelhos), which are subdivided into more than 4000 parishes (freguesia/freguesias). Municipalities are grouped for administrative purposes into superior units. For continental Portugal the municipalities are gathered in 18 districts, while the islands have a regional government directly above them. Since 1976, the main classifications have been either mainland Portugal or the autonomous regions of Portugal (Azores and Madeira), since 1978. The autonomies have regional governments that are constituted by the regional government president and by regional secretaries. The Portuguese territory was reorganized in accordance with a system of statistical regions and subregions known as N.U.T.S. (Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics) that are the basis of the statistical system of information for the entire European Union.

Economy

Portugal has become a diversified and increasingly service-based economy since joining the European Community in 1986. Over the past two decades, successive governments have privatized many state-controlled firms and liberalized key areas of the economy, including the financial services and telecommunications sectors. Portugal was one of the founding countries of the euro in 1999, and therefore is integrated into the Eurozone.

Major industries include oil refineries, automotive, cement production, pulp and paper industry, textile, footwear, furniture, and cork (of which Portugal is the world's leading producer). Agriculture and fishing no longer represents the bulk of the economy, but Portuguese wines, namely Port wine (named after the country's second largest city, Porto) and Madeira wine (named after Madeira Island), are exported worldwide. Tourism is also important, especially in mainland Portugal's southernmost region of the Algarve and in the Atlantic Madeira archipelago.

Economic growth had been above the EU average for much of the 1990s, but fell back in 2001-2006. GDP per capita stands at roughly two-thirds of the EU-25 average, at $23,464—a rank of 34th out of 194 countries. A poor educational system, in particular, has been an obstacle to greater productivity and growth. The Global Competitiveness Report for 2005 places Portugal on the 22nd position, ahead of countries like Spain, Ireland, France, Belgium and Hong Kong. This represents an increase of two places from the 2004 ranking. Portugal was ranked 20th on the Technology index and 15th on the Public Institutions index. The Economist Intelligence Unit places Portugal as the country with the nineteenth-best quality of life in the world, ahead of other economically and technologically advanced countries like France, Germany, the United Kingdom and South Korea.

In 2006, the world's largest solar power plant began operating in the nation's south while the world's first commercial wave power farm opened in October 2006 in the Norte region. As of 2006, 55 percent of electricity production was from coal and fuel power plants. The other 40 percent was produced by hydroelectrics and five percent by wind energy. The government was channeling $3.8-billion into developing renewable energy sources over the subsequent five years.

Transportation was seen as a priority in the 1990s, pushed by the growing use of automobiles and industrialization. The country has a 42,708 mile (68,732km) network of roads, of which almost 1864 miles (3000km) are part of a 44 motorway system. The two principal metropolitan areas have subway systems: Lisbon Metro and Metro Sul do Tejo in Lisbon Metropolitan Area and Porto Metro in Porto, each with more than 22 miles (35km) of lines. Construction of a high-speed TGV line connecting Porto with Lisbon and Lisbon with Madrid will begin in 2008; it will replace the Pendolinos. Lisbon's geographical position makes it a stopover point for many foreign airlines. The most important airports are in Lisbon, Faro, Porto, Funchal (Madeira), and Ponta Delgada (Azores).

Exports totaled $43.58-billion in 2006. Export commodities included clothing and footwear, machinery, chemicals, cork and paper products, and hides. Export partners included Spain 26.5 percent, Germany 12.9 percent, France 12 percent, UK 6.7 percent, US 6.1 percent. Imports totaled $64.45-billion in 2006. Import commodities included machinery and transport equipment, chemicals, petroleum, textiles, agricultural products. Import partners included Spain 29 percent, Germany 13.1 percent, France 8.1 percent, Italy 5.6 percent, and the Netherlands 4.4 percent. The unemployment rate was 7.6 percent in 2006.

Demographics

Population

As of 2007, Portugal had 10,848,692 inhabitants of whom about 418,000 were legal immigrants. Portugal, long a country of emigration, has now become a country of net immigration, and not just from the former Indian and African colonies. By the end of 2003, legal immigrants represented about five percent of the population, and the largest communities were from Brazil, Ukraine, Romania, Cape Verde, Angola, Russia, Guinea-Bissau and Moldova with other immigrants from parts of Latin America, China and Eastern Europe. Life expectancy at birth in 2007 was 77.87 years.

Ethnicity

Portugal's population has been remarkably homogeneous, helping it become the first unified nation-state in Western Europe. For centuries Portugal had virtually no ethnic, tribal, racial, religious, or cultural minorities. Native Portuguese are ethnically a combination of pre-Roman Celts along with some other minor contributions by Romans, Germanic (Visigoths, Suebi), Jews and Moors (mostly Berbers and some Arabs). Citizens of black African descent who immigrated to the mainland during decolonization number fewer than 100,000. Since 1990 East Europeans have entered Portugal. The recently-arrived population of immigrants, from former colonies in Africa and Asia, are residentially segregated in Lisbon neighborhoods with poor housing, even though anti-racism laws prohibit and penalize racial discrimination in housing, business, and health services.

Religion

Portugal, like most European countries has no state religion, making it a secular state. The great majority of the Portuguese population (84 percent) belongs to the Roman Catholic Church, but only about 19 percent attend Mass and take the sacraments regularly. A larger number wish to be baptized, married in the church, and receive last rites. Religious observance remains somewhat strong in northern areas, with the population of Lisbon and southern areas generally less devout.

Religious minorities include a little over 300,000 Protestants. There are also about 50,000 Muslims and 10,000 Hindus. Most of them came from Goa, a former Portuguese colony on the west coast of India (Some Muslims also came from former Portuguese African colonies with important Muslim minorities: Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, and São Tomé and Príncipe). There are also about 1000 Jews. Portugal is home to less than 10,000 Buddhists, mostly Chinese from Macau and a few Indians from Goa. There are between 420,960 to 947,160 (4 to 9 percent of total population) atheists and agnostics.

Although church and state were formally separated during the Portuguese First Republic (1910-1926), a separation reiterated in the constitution of 1976, Catholic precepts continue to have an important weight in the Portuguese society. Many Portuguese holidays and festivals have religious origins. The educational and health care systems were for a long time the church's preserve, and many times when a building, bridge, or highway is opened, it receives the blessing of the clergy.

The practice of religion in Portugal showed striking regional differences. Even in the early 1990s, 60 to 70 percent of the population in the traditionally Roman Catholic north regularly attended religious services, compared with 10 to 15 percent in the historically anticlerical south. In the greater Lisbon area, about 30 percent were regular churchgoers.

The most famous of Portuguese religious events was the supposed apparition of the Virgin Mary to three children in 1917 in the village of Fátima in the province of Santarém. Hundreds of thousands of pilgrims have visited the shrine at Fátima in the belief that the pilgrimage could bring about healing.

Language

Portuguese, the official language, is a Romance language that originated in what is now Galicia (Spain) and northern Portugal from the Latin spoken by romanized Celts about 1000 years ago. It spread worldwide in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries as Portugal established a colonial and commercial empire which spanned from Brazil in the Americas to Goa in India and Macau in China. During that time, many creole languages based on Portuguese also appeared around the world, especially in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean.

Today it is one of the world's major languages, ranked sixth according to number of native speakers (over 200 million). It is the language with the largest number of speakers in South America (188 million, over 51 percent of the continent's population), and also a lingua franca in Africa. It is the official language of nine countries.

Mirandese language, another Romance language, is sparsely spoken in a small area of northeastern Portugal, in the Miranda do Douro municipality. The Portuguese Parliament granted it co-official recognition (along with Portuguese language) for local matters.

Marriage and the family

The 1976 constitution outlawed discrimination by sex, and divorce and abortion became legal. Women have outpaced men in higher education, and Portugal has had one woman serve as president. However, women still perform the major domestic chores, although more men are involved in child care. Illegitimacy remains high in rural northern Portugal. Households in the north tend to consist of a three-generation family, whereas in the south households are generally composed of a nuclear family. In the north, the married couple heads the household, whereas among urban middle-class and in the south, the dominant male is head of the household.

Education

Education is a subject of controversy due to its complexities and state of flux. There are also concerns related to the large dropout rates (mostly in the secondary and higher education systems), the high multi-generational functional illiteracy (48 percent = ~ 5,100,000 functional illiterates) and illiteracy rates (7.5 percent = ~ 800,000 illiterates), which is a quite mediocre statistical record when compared with other developed countries. The education system of Portugal is regulated by the State through the Ministry of Education, and the Ministry of Science and Technology and Higher Education. The public education system is the most popular and well established, but there are also many private schools at all levels of education.

Higher education in Portugal is divided into two main subsystems: university and polytechnic education, and it is provided in autonomous public universities, private universities, public or private polytechnic institutions and higher education institutions of other types. The university system has a strong theoretical basis and is highly research-oriented; the non-university system provides a more practical training and is profession-oriented.

Portuguese universities have existed since 1290. Scientific and technological research activities in Portugal are mainly conducted within a network of R&D units belonging to public universities and state-managed autonomous research institutions like the INETI - Instituto Nacional de Engenharia, Tecnologia e Inovação.

Class

At the end of the Second World War, Portugal had a small upper class, a small middle class, a small urban working class, and a mass of rural peasants. There was little social mobility, and a distinction was made between those who worked with their hands and those who did not. The rural south had a massive population of landless day laborers which enabled the Communist Party to grow strong in the south after the 1974 revolution. The 1976 constitution defined Portugal as a republic engaged in the formation of a classless society. Since then, Portugal has become less socially rigid, and education is an avenue to social mobility. The middle class has grown and the peasant population has declined, but a gap remains between the social, economic, and political elites from the bulk of the population.

Culture

The culture of Portugal is rooted in the Latin culture of Ancient Rome, with a Celtiberian background (a mixture of pre-Roman Celts and Iberians). Portugal has a rich traditional folklore (Ranchos Folclóricos), with great regional variety. Many towns have a museum and a collection of ancient monuments and buildings. Many places have at least a cinema, some venues to listen to music and locations to see arts and crafts.

Architecture

Portugal has been the location of important construction since the second millennium B.C.E. The pre-Roman Citânia de Briteiros in Guimarães is a good example of native architecture. The houses were round, built from granite without mortar, in settlements (castros) in the mountains, and were surrounded by protective walls. The Romans built aqueducts, bridges and roads, along with theaters, temples, circuses and other public buildings. There are particular ruins of buildings made by the Romans, called Centum Cellas whose purpose has yet to be discovered.

Portugal has scores of medieval castles. Romanesque and Gothic influences have given Portugal some of its greatest cathedrals, and in the sixteenth century a national style (Arte Manuelina) was synthesized. There are numerous examples of Restoration architecture (1640-1717), the Baroque style (1717-1755), the Pombaline style (1755-1780), which is a secular, utilitarian architecture used after the 1755 Lisbon earthquake.

Modern Portugal has given the world renowned architects like Eduardo Souto de Moura, Álvaro Siza Vieira and Gonçalo Byrne. Internally, Tomás Taveira is also noteworthy. One of the top architecture schools in the world, known as "Escola do Porto" or School of Porto, is located in Portugal. Its alumni include Álvaro Siza (winner of a Pritzker prize) and Eduardo Souto de Moura.

Azulejos, glazed ceramic tiles that cover the facades and interiors of churches, government buildings, and private homes, characterize Portuguese architecture. Azulejos, introduced by the Moors, use both geometric and representational patterns. Traditional peasant houses in the north often have two stories and a red tubular clay tile roof, and were built with thick granite walls and verandas. The south commonly had one-story, whitewashed, flat-roofed houses with blue trim around the windows and doorways, built to keep out the summer heat.

Art

Portuguese art was limited during the reconquista to a few paintings in churches, convents and palaces. Artist Nuno Gonçalves is credited for painting, during the reign of King Alfonso V (1432-1481), the Saint Vincent Panels, which depict Portuguese clergy, nobility, and common people. His influence on Portuguese art continued after his death.

During the Golden Age of Portugal, in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, Portuguese artists were influenced by Flemish art, and were in turn influential on Flemish artists of the same period. Little is known about the artists of this time due to the medieval culture that considered painters to be artisans. The anonymous artists in the Portuguese "escolas" produced art for metropolitan Portugal and for its colonies, namely Malacca or Goa and even Africa.

In the nineteenth century, naturalist and realist painters like Columbano, Henrique Pousão and Silva Porto revitalized painting against a decadent academic art. The twentieth century saw the arrival of Modernism, and the most prominent Portuguese painter Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso, who was heavily influenced by French painters. Another great modernist painter/writer was Almada Negreiros. He was deeply influenced by both Cubist and Futurist trends. Prominent international figures in visual arts in the late twentieth century included painters Vieira da Silva, Júlio Pomar, and Paula Rego.

Cuisine

Portuguese cuisine is characterized by rich, filling and full-flavored dishes and is a prime example of a Mediterranean diet. The influence of Portugal's former colonial possessions is clear in the wide variety of spices used. These include piri piri (small, fiery chilli peppers), as well as cinnamon, vanilla and saffron. There are also Arab and Moorish influences, especially in the south of the country. Olive oil is one of the bases of Portuguese cuisine both for cooking and flavoring meals. Garlic is widely used, as are herbs such as coriander and parsley.

Portuguese wines have deserved international recognition since the times of the Roman Empire, which associated Portugal with their God Bacchus. Some of the best Portuguese wines are: Vinho Verde, Vinho Alvarinho, Vinho do Douro, Vinho do Alentejo, Vinho do Dão, Vinho da Bairrada and the sweet: Port wine, Madeira wine and the Moscatel from Setúbal and Favaios.

Literature

Until 1350, the Portuguese-Galician troubadours roamed the Iberian Peninsula. Gil Vicente (c.1465 - 1536), was one of the founders of Portuguese and Spanish dramatic traditions. Adventurer and poet Luís de Camões (ca. 1524-1580) wrote the epic poem The Lusiads, with Virgil's Aeneid as his main influence. Modern Portuguese poetry is rooted in neoclassic and contemporary styles, as exemplified by Fernando Pessoa (1888–1935). Modern Portuguese literature is represented by authors such as Almeida Garrett, Camilo Castelo Branco, Eça de Queirós, Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen, and António Lobo Antunes. Particularly popular and distinguished is José Saramago, winner of the 1998 Nobel Prize for literature.

Music

Portuguese music encompasses a wide variety of genres. The most renowned is fado, a melancholy urban music, usually associated with the Portuguese guitar and saudade, or longing. Coimbra fado, a unique type of fado, is also noteworthy. Internationally notable performers include Amália Rodrigues, Carlos Paredes, José Afonso, Mariza, Carlos do Carmo, Mísia, and Madredeus. One of the largest international Goa trance festivals takes place in northern Portugal every two years, and the student festivals of Queima das Fitas are major events in a number of cities across Portugal.

Theatre

Gil Vicente, seen has the father of Portuguese theatre, was the leading Portuguese playwright in the sixteenth century, satirically portraying the society of the time. António Ferreira (1528-1569) is considered the father of Renaissance culture in Portugal. António José da Silva (1705-1739), commonly known as "O Judeu" because of his Judaic origins, wrote "Os Encantos de Medeia" (1735), "As Variedades de Proteu" (1737) and "Precipício de Faetonte" (1738). In the twentieth century theatre in Portugal became more popular with the "Revista" – a form of humorous and cartoonish theatre designed to expose and criticize social (and political) issues. The most important actors in this genre were Vasco Santana (1898-1958), Beatriz Costa (1907-1996) and Ivone Silva (1935-1987). Maria João Abreu, José Raposo and Fernando Mendes, who performed this form of theatre at the end of the twentieth century at the well known "Parque Mayer."

Sports

Football (soccer) is the most known, loved and practiced sport. The legendary Eusébio is still a symbol of Portuguese football history and Luís Figo and Cristiano Ronaldo are among the numerous examples of other world class footballers born in Portugal and noted worldwide. The Portuguese national teams, have titles in the FIFA World Youth Championship and in the UEFA youth championships. The main national team - Selecção Nacional - finished second in Euro 2004, and reached the third place in the 1966 FIFA World Cup.

Portugal has a successful rink hockey team, with 15 world titles and 20 European titles, making it the country with the most wins in both competitions. The most successful Portuguese rink hockey clubs in the history of European championships are F.C. Porto, S.L. Benfica, Sporting CP, and Óquei de Barcelos.

The national rugby union team made a dramatic qualification into the 2007 Rugby World Cup and become the first all amateur team to qualify for the World Cup since the dawn of the professional era. The Portuguese national team of rugby sevens has performed well, becoming one of the strongest teams in Europe, and proved their status as European champions in several occasions.

Rui Silva, in men's athletics, has won several gold, silver and bronze medals in the European, World and Olympic Games competitions. Francis Obikwelu in the 100 m and the 200 m, had silver in the 2004 Summer Olympics. Naide Gomes in pentathlon and long jump, is another Portuguese elite athlete. In the triathlon, Vanessa Fernandes, has won a large number of medals and major competitions across the world and in 2007 became the world champion both in Triathlon and Duathlon. In judo, Telma Monteiro is European champion in the women's under-52 kg category. Nelson Évora is world champion in triple jump.

Cycling, with Volta a Portugal being the most important race, is also a popular sports event and include professional cycling teams such as S.L. Benfica, Boavista, Clube de Ciclismo de Tavira, and União Ciclista da Maia. Noted Portuguese cyclists include, among others, names as Joaquim Agostinho, Marco Chagas, José Azevedo and Sérgio Paulinho.

The country has also achieved notable performances in sports like fencing, surfing, windsurf, kitesurf, kayaking, sailing and shooting, among other. The paralympic athletes have also conquered many medals in sports like swimming, boccia and wrestling. Portugal has its own original martial art, jogo do pau, in which the fighters use staffs to confront one or several opponents.

Notes

- ↑ ITDS, Rui Campos, Pedro Senos. Statistics Portugal. Ine.pt. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- ↑ Pordata, "Base de Dados Portugal Contemporâneo". Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- ↑ Censos 2011, Resultados Preliminares 2011 Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Error on call to template:cite web: Parameters url and title must be specified. International Monetary Fund.

- ↑ Gini Index. Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- ↑ The Euromosaic study, Mirandese in Portugal, europa.eu – European Commission website. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- de Macedo, Newton, and José Hermano Saraiva. História de Portugal III - A Epopeia dos Descobrimentos. QuidNovi, 2004. ISBN 9895541082

- de Macedo, Newton, and José Hermano Saraiva. História de Portugal IV - Glória e Declínio do Império. QuidNovi, 2004. ISBN 9895541090

- Maxwell, Kenneth. The making of Portuguese democracy. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 9780521460774

- Opello, Walter C. Portugal from monarchy to pluralist democracy. (Westview profiles.) Boulder: Westview Press, 1991. ISBN 9780813304885

- Pinto, António Costa. Modern Portugal. Palo Alto, CA: Society for the Promotion of Science and Scholarship, 1998. ISBN 9780930664176

- Ribeiro, Ângelo, and Saraiva. José Hermano. História de Portugal I - A Formação do Território. QuidNovi, 2004. ISBN 9895541066

- Ribeiro, Ângelo, and Saraiva, José Hermano. História de Portugal II - A Afirmação do País QuidNovi, 2004. ISBN 9895541074

- Ribeiro, Ângelo, and José Hermano Saraiva. História de Portugal V - A Restauração da Indepêndencia. QuidNovi, 2004. ISBN 9895541104

- Wheeler, Douglas L. Historical dictionary of Portugal. (European historical dictionaries, no. 1.) Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1993. ISBN 9780810826960

External links

All links retrieved November 30, 2022.

- Culture of Portugal Countries and their cultures.

- Portugal BBC Country Profiles.

- Portugal U.S. Department of State.

- Portugal economist.com.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Portugal history

- History_of_Portugal history

- History_of_Portugal_1112-1279 history

- Estado_Novo_Portugal history

- History_of_Portugal_1974-1986 history

- Politics_of_Portugal history

- Economy_of_Portugal history

- Demographics_of_Portugal history

- Religion_in_Portugal history

- Portuguese_language history

- Education_in_Portugal history

- Culture_of_Portugal history

- Portuguese_cuisine history

- Cinema_of_Portugal history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

.jpg/300px-Castelo_de_Guimarães_(Portugal).jpg)

.jpeg/200px-Mário_Soares_(2003).jpeg)