| Books of the |

Psalms (Greek: Psalmoi) is a book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. The term originally meant "songs sung to a harp," from the Greek word psallein (Ψαλμοί), "to play on a stringed instrument." The Hebrew term for Psalms is Tehilim, (תהילים).

In the Hebrew Bible, the Psalms are counted among the "Writings" or Ketuvim, one of the three main sections into which the books are grouped. The Book of Psalms, especially if printed separately and set for singing or chanting, is also called the Psalter.

Traditionally, most of the Psalms are ascribed to King David. However, modern scholarship generally doubts that the Psalms in their current form could be that ancient. They represent widely varied literary types, and their themes range from praise and thanksgiving to mourning, Temple liturgies, enthronement songs, processions, war hymns, prayers of supplication during times of personal and national trial, pleas for vengeance on one's personal enemies, messianic prophecies, acrostic literary exercises, and even a marriage song.

The Psalms play a major role in the worship tradition of both Jews and Christians and provide an important point of continuity in the Judeo-Christian tradition.

Composition of the Book of Psalms

The Book of Psalms is divided into 150 Psalms, most of which constitute a distinct religious song or chant, although one or two are atypically long and may constitute a set of related songs. Psalm 117 is the shortest Psalm, containing only two verses:

| “ | Praise the Lord, all you nations; extol him, all you peoples. For great is his love toward us, and the faithfulness of the Lord endures forever. Praise the Lord. | ” |

Psalm 119 is the longest, being composed of 176 verses.

When the Bible was divided into chapters, each Psalm was assigned its own chapter and number. The organization and numbering of the Psalms differs between the (Masoretic) Hebrew and the (Septuagint) Greek manuscripts of the Book of Psalms. These differences are also reflected in various versions of the Christian and Hebrew Bibles:

| Hebrew Psalms | Greek Psalms |

|---|---|

| 1-8 | |

| 9-10 | 9 |

| 11-113 | 10-112 |

| 114-115 | 113 |

| 116 | 114-115 |

| 117-146 | 116-145 |

| 147 | 146-147 |

| 148-150 | |

The differences are accounted for by the following:

- Psalms 9 and 10 in the Hebrew are brought together as Psalm 9 in the Greek.

- Psalms 114 and 115 in the Hebrew are Psalm 113 in the Greek.

- Psalms 114 and 115 in the Greek appear as Psalm 116 in the Hebrew.

- Psalms 146 and 147 in the Greek form Psalm 147 in the Hebrew.

Hebrew Bibles generally use the Masoretic, or Hebrew text. Christian traditions vary:

- Protestant translations are based on the Hebrew numbering;

- Eastern Orthodox translations are based on the Greek numbering;

- Roman Catholic official liturgical texts follow the Greek numbering, but modern Catholic translations often use the Hebrew numbering, sometimes adding, in parenthesis, the Greek numbering as well.

Most manuscripts of the Septuagint also include a Psalm 151, present in Eastern Orthodox translations. A Hebrew version of this poem was found in the Psalms Scroll of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The Psalms Scroll also presents the Psalms in an order different from that found elsewhere and contains a number of non-canonical poems and hymns. A substantial number of songs are found outside of the Book of Psalms in other biblical books, where they usually appear in the mouths of biblical characters at significant moments.

For the remainder of this article, the Hebrew Psalm numbers will be used unless otherwise noted.

Authorship and ascriptions

Most of the Psalms are prefixed with introductory words ascribing them to a particular author or giving a detail about their function or the circumstances of their composition. Jewish and Christian tradition maintains that most of the Psalms are the work of David, especially the 73 Psalms which specifically bear his name.

Many modern scholars, however, see the Psalms as the product of several authors or groups of authors, many unknown, and most from a much later period than that of David. Literary scholars believe the Psalms were not written down in Hebrew before the sixth century B.C.E., nearly half a millennium after David's reign. The older Psalms thus depended on oral or hymnic tradition for transmission.

Psalms 39, 62, and 77 are linked with Jeduthun, to be sung after his manner or in his choir. Psalms 50 and 73-83 are associated with Asaph, as the master of his choir, to be sung in the worship of God. The ascriptions of Psalms 42, 44-49, 84, 85, 87, and 88 assert that the "sons of Korah" were entrusted with arranging and singing them.

Psalm 18 is found, with minor variations, also at 2 Samuel 22, for which reason, in accordance with the naming convention used elsewhere in the historic parts of the Bible, it is known as the Song of David. Several hymns are included in other biblical texts but not found in the Book of Psalms.

Psalm forms

| “ | God has ascended amid shouts of joy, the Lord amid the sounding of trumpets.

|

” |

Psalms can be classified according to their similarities. Such categories may overlap, and other classifications are also possible:

- Hymns

- Individual Laments

- Community Laments

- Songs of Trust

- Individual Thanksgiving Psalms

- Royal Psalms

- Wisdom Psalms

- Pilgrimage Psalms

- Liturgy Psalms

Additional forms include:

- Songs of Zion—Psalms 48, 76, 84, 87, 122, 134;

- Historical Litanies—Psalms 78, 105, 106, 135, 136;

- Pilgrim Liturgies—Psalms 81, 21;

- Entrance Liturgies—Psalms 15, 24;

- Judgment Liturgies—Psalms 50, 82;

- Mixed Types—36, 40, 41, 68

Psalm 119, the longest Psalm at 176 verses, is composed in sets of eight verses, each set beginning with one of the 22 Hebrew letters. Several other Psalms also have alphabetical arrangements. These psalms are believed to be written (rather than oral) compositions when they were composed, and are thus of a relatively late date.

Some of the titles given to the Psalms in their ascriptions suggest their use in worship:

- Some bear the Hebrew designation shir (Greek ode, a song). Thirteen have this title.

- Fifty-eight Psalms bear the designation mizmor (Greek psalmos), a lyric ode or a song set to music; a sacred song accompanied with a musical instrument.

- Psalm 145, and several others, have the designation tehillah (Greek hymnos, a hymn), meaning a song of praise; a song the prominent thought of which is the praise of God.

- Six Psalms (16, 56-60) have the title (Hebrew) michtam.

- Psalm 7 bears the unknown title (Hebrew) shiggaion.

Critical views

A common critical opinion of the Book of Psalms is that it is basically a hymn-book of the congregation of Israel during the existence of the Second Temple from the fourth century B.C.E. through the first century C.E.

However, some of the older Psalms bear a strong resemblance to the hymnic traditions of the surrounding nations. Psalm 118, for example, describes God in terms reminiscent of Canaanite descriptions of the storm deity Baal, with fire from his nostrils while riding on dark clouds among lightning and thunder. Psalm 82 describes God as ruling over an assembly of gods, hinting at the polytheistic origins of the Hebrew religion.

While some of the Psalms may thus indeed be quite ancient, it is doubtful that many of them could have been composed by King David. Indeed, most of those ascribed to him clearly describe a later period, in which the Temple of Jerusalem has already been built, or the Jews have already been taken in exile. Many also describe the attitude not of a king, but of priests devoted to the Temple, using language that relates to the post-exilic period. A number of prominent scholars suggest that most of the Psalms, in their present form, actually date from the second century B.C.E., not the eleventh century of David's era. This does not rule out however, than many of the Psalms may have originated much earlier, undergoing a process of modification before reaching their present form.

Jewish usage

Sections of the book

In Jewish usage, the Psalter is divided, after the analogy of the Pentateuch, into five books, each closing with a doxology or benediction:

- The first book comprises the first 41 Psalms. All of these are ascribed to David except Psalms 1, 2, 10, and 33, which, though untitled in the Hebrew, were also traditionally ascribed to David. While Davidic authorship cannot be confirmed, many believe this probably is generally the oldest section of the Psalms.

- The second book consists of the next 31 Psalms 42-72. Of these, 18 are ascribed to David. Psalm 72 begins "For Solomon," but is traditionally understood as being written by David as a prayer for his son. The rest are anonymous.

- The third book contains 17 Psalms 73-89, of which Psalm 86 is ascribed to David, Psalm 88 to Heman the Ezrahite, and Psalm 89 to Ethan the Ezrahite. The others are anonymous.

- The fourth book also contains 17 Psalms (90-106), of which Psalm 90 is ascribed to Moses, and Psalms 101 and 103 to David.

- The fifth book contains the remaining 44 Psalms. Of these, 15 are ascribed to David, and one (Psalm 127) is a charge to Solomon.

Psalms 113-118 constitute the Hallel (praise or thanksgiving), which is recited on the three great feasts, (Passover, Weeks, and Tabernacles); at the new moon; and on the eight days of Hanukkah. Psalm 136 is generally called "the great Hallel." A version of Psalm 136 with slightly different wording appears in the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Psalms 120-134 are referred to as Songs of Degrees, and are thought to have been used as hymns of approach by pilgrims to the Temple in Jerusalem.

Psalms in Jewish ritual

Psalms are used throughout traditional Jewish worship. Many complete Psalms and verses from them appear in the morning services. Psalm 145 (commonly referred to as "Ashrei"), is read during or before services, three times every day. Psalms 95-99, 29, 92, and 93, along with some later readings, comprise the introduction ("Kabbalat Shabbat") to the Friday night service.

Traditionally, a different "Psalm for the Day" is read after the morning service each day of the week (starting Sunday, Psalms: 24, 48, 82, 94, 81, 93, 92). This is described in the Mishnah (the initial codification of the Jewish oral tradition) in the tractate "Tamid."

From the beginning of the summer month of Elul until the last day of the fall festival of Sukkot, Psalm 27 is recited twice daily by traditional Jews.

When a Jew dies, a watch is kept over the body and Psalms are recited constantly by sun or candlelight, until the burial service. Historically, this watch would be carried out by the immediate family – usually in shifts – but in contemporary practice, this service is provided by an employee of the funeral home or Chevra kadisha.

Many observant Jews complete the Book of Psalms on a weekly or monthly basis. Some also say, each week, a Psalm connected to that week's events or the Torah portion read during that week. On the Sabbath preceding the appearance of the new moon, some Jews (notably Lubavitch and other Hasidic Jews) read the entire Book of Psalms prior to the morning service.

The Psalms are especially recited in times of trouble, such as poverty, disease, or physical danger. In many synagogues, Psalms are recited after services for the security of the State of Israel.

The Psalms in Christian worship

The 116 direct quotations from the Psalms in the New Testament show that they were familiar to the Judean community in the first century of the Christian era. The Psalms in worship, and the Psalms have remained an important part of worship in virtually all Christian churches.

The Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic and Anglican Churches have traditionally made systematic use of the Psalms, with a cycle for the recitation of all or most of them over the course of one or more weeks. In the early centuries of the Church, it was expected that any candidate for bishop would be able to recite the entire Psalter from memory, something they often learned automatically during their time as monks. Today, new translations and settings of the Psalms continue to be produced. Several conservative denominations sing only the Psalms in worship, and do not accept the use of any non-biblical hymns. Examples include the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America, the Westminster Presbyterian Church in the United States and the Free Church of Scotland.

Some Psalms are among the best-known and best-loved passages of scripture, in the Christian tradition with a popularity extending well beyond regular church-goers. In particular, the 23rd Psalm ("The Lord is My Shepherd") offers an immediately appealing message of comfort and is widely chosen for church funeral services, either as a reading or in one of several popular hymn settings. Psalm 51 ("Have mercy on me O God,") is by far the most sung Psalm of Orthodoxy, in both Divine Liturgy and Hours, in the sacrament of repentance or confession, and in other settings. Psalm 103 ("Bless the Lord, O my soul; and all that is within me, bless his holy name!") is one of the best-known prayers of praise. Psalm 137 ("By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down and wept") is a moody, yet eventually triumphant, meditation upon living in captivity.

Eastern Orthodox usage

Eastern Orthodox Christians and Eastern Catholics who follow the Byzantine rite, have long made the Psalms an integral part of their corporate and private prayers. To facilitate its reading, the 150 Psalms are divided into 20 kathismata, and each kathisma is further subdivided into three staseis.

At vespers and matins, different kathismata are read at different times of the liturgical year and on different days of the week, according to the Church's calendar, so that all 150 psalms (20 kathismata) are read in the course of a week. In the twentieth century, some lay Christians have adopted a continuous reading of the Psalms on weekdays, praying the whole book in four weeks, three times a day, one kathisma a day.

Aside from kathisma readings, Psalms occupy a prominent place in every other Orthodox service including the services of the Hours and the Divine Liturgy. In particular, the penitential Psalm 50 is very widely used. The entire book of Psalms is traditionally read out loud or chanted at the side of the deceased during the time leading up to the funeral, mirroring Jewish tradition.

Roman Catholic usage

The Psalms have always been an important part of Roman Catholic liturgy. The Liturgy of the Hours is centered on chanting or recitation of the Psalms, using fixed melodic formulas known as psalm tones. Early Catholics employed the Psalms widely in their individual prayers also.

Until the Second Vatican Council the Psalms were either recited on a one-week or a two-week cycle. The Breviary introduced in 1974 distributed the Psalms over a four-week cycle. Monastic usage varies widely.

Over the centuries, the use of complete Psalms in the liturgy declined. After the Second Vatican Council longer Psalm texts were reintroduced into the Mass, during the readings. The revision of the Roman Missal reintroduced the singing or recitation of a more substantial section of a Psalm, in some cases an entire Psalm, after the first Reading from Scripture.

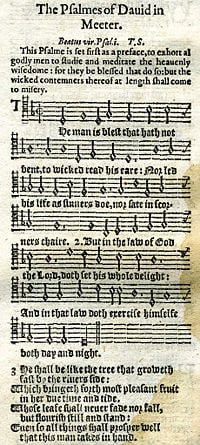

Protestant usage

The Psalms were extremely popular among those who followed the Reformed tradition. Following the Protestant Reformation, verse paraphrases of many of the Psalms were set as hymns. These were particularly popular in the Calvinist tradition, where in the past they were typically sung to the exclusion of hymns. Calvin himself made some French translations of the Psalms for church usage. Martin Luther's A Mighty Fortress is Our God is based on Psalm 46. Among famous hymn settings of the Psalter were the Scottish Psalter and the settings by Isaac Watts. The first book printed in North America was a collection of Psalm settings, the Bay Psalm Book (1640).

In the Church of England, Anglican chant is a way of singing the Psalms that remains part of the Anglican choral tradition to this day.

However, by the twentieth century Psalms were mostly replaced by hymns in mainline church services. In the Black churches of America, however, Psalms such as the 23rd Psalm are often sung by soloists and church choirs. A number of Psalms, or sections of them, have also been set to music in the contemporary "praise music" genre and are used in various settings, from megachurches to youth camps, and charismatic revivals.

The Psalms are popular for private devotion among many Protestants. There exists in some circles a custom of reading one Psalm and one chapter of Proverbs a day, corresponding to the day of the month. The Book of Psalms is also a popular topic for Bible study meetings in private homes.

Example: Psalm 150

| “ | Praise the Lord.

|

” |

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brueggemann, Walter. The Message of the Psalms - A Theological Commentary. Augsburg Old Testament studies. Minneapolis: Augsburg Pub. House, 1984. ISBN 978-0806621203

- Flint, Peter W., Patrick D. Miller, Aaron Brunell, and Ryan Roberts. The Book of Psalms: Composition and Reception. Leiden: Brill, 2005. ISBN 978-9004136427

- Human, Dirk J. Psalms and Mythology. Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament studies, 462. New York: T & T Clark, 2007. ISBN 0567029824

- Human, Dirk J., and C. J. A. Vos. "Psalms and Liturgy." Journal for the study of the Old Testament 410. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 2004. ISBN 978-0567080660

- Wallace, Howard N. Words to God, Word from God: The Psalms in the Prayer and Preaching of the Church. Aldershot, Hampshire, England: Ashgate Pub, 2004. ISBN 978-0754636922

External links

All links retrieved November 18, 2023.

- Translation with Rashi's commentary. chabad.org.

- NIV and other translations. biblegateway.com.

This entry incorporates text from the public domain Easton's Bible Dictionary, originally published in 1897.

| |||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.