Pyramid

- This article is about pyramid-shaped structures. For the geometric shape, see Pyramid (geometry).

A pyramid (from Greek: πυραμίς pyramís) is a structure whose outer surfaces are triangular and converge to a single step at the top, making the shape roughly a pyramid in the geometric sense. A pyramid's design, with the majority of the weight closer to the ground, allowed early civilizations to create stable monumental structures.

Civilizations in many parts of the world have built pyramids, generally for religious and burial purposes. Many have temples at the top, while others serve as monumental tombs for kings, often built as a physical gateway to the heavens where the dead spend their afterlife. The largest pyramid by volume is the Mesoamerican Great Pyramid of Cholula, in the Mexican state of Puebla. The Great Pyramid in Egypt is the only one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World still remaining.

Description

A pyramid (from Greek: πυραμίς pyramís) meaning "a kind of cake of roasted wheat-grains preserved in honey." The Egyptian pyramids were named after its form.[1][2] is a structure whose outer surfaces are triangular and converge to a single step at the top, making the shape roughly a pyramid in the geometric sense. The base of a pyramid can be trilateral, quadrilateral, or of any polygon shape. As such, a pyramid has at least three outer triangular surfaces (at least four faces including the base). The square pyramid, with a square base and four triangular outer surfaces, is a common version.

A pyramid's design, with the majority of the weight closer to the ground and with the pyramidion at the apex, means that less material higher up on the pyramid will be pushing down from above. This distribution of weight allowed early civilizations to create stable monumental structures.

Pyramid power

Pyramid power is based on the understanding that God created the universe according to a geometric plan, and that there are energy fields created by sacred geometry. This has led to the belief that the ancient Egyptian pyramids and objects of similar shape can confer a variety of benefits.[3] Among these assumed properties are the ability to preserve foods, amplify thought forms, and improve health: "some people report having been 'so energized that they could not cope with the dynamo effects they experienced'"[4] among other effects. Such unverified conjectures regarding pyramids are collectively known as pyramidology.

However, skeptics report that there is no scientific evidence that pyramid power exists: "There is no satisfactory evidence to support the theory of pyramid power. Although the pyramids are impressive structures, their particular construction—their shape and geographical orientation—does not seem to be capable of altering fundamental physical processes."[5]

Ancient pyramids

Civilizations in many parts of the world have built pyramids. The largest pyramid by volume is the Mesoamerican Great Pyramid of Cholula, in the Mexican state of Puebla. For centuries, the largest structures on Earth have been pyramids—first the Red Pyramid in the Dashur Necropolis and then the Great Pyramid of Khufu, both in Egypt—the latter is the only one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World still remaining.

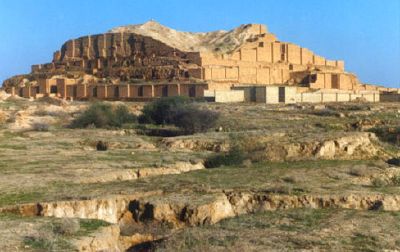

West Asia

The Mesopotamians built the earliest pyramidal structures, called ziggurats. In ancient times, these were brightly painted in gold/bronze. Since they were constructed of sun-dried mud-brick, little remains of them. Ziggurats were built by the Sumerians, Babylonians, Elamites, Akkadians, and Assyrians for local religions. Each ziggurat was part of a temple complex which included other buildings. The precursors of the ziggurat were raised platforms that date from the Ubaid period.[6]

Built in receding tiers upon a rectangular, oval, or square platform, the ziggurat was a pyramidal structure with a flat top. Sun-baked bricks made up the core of the ziggurat with facings of fired bricks on the outside. The facings were often glazed in different colors and may have had astrological significance. Kings sometimes had their names engraved on these glazed bricks. The number of tiers ranged from two to seven. It is assumed that they had shrines at the top, but there is no archaeological evidence for this and the only textual evidence is from Herodotus.[6] Access to the shrine would have been by a series of ramps on one side of the ziggurat or by a spiral ramp from base to summit.

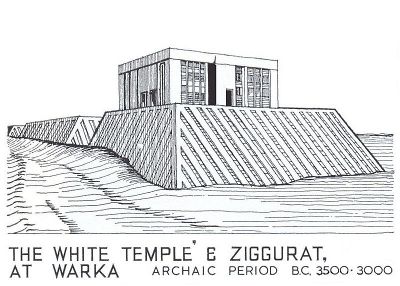

The earliest ziggurats began near the end of the Early Dynastic Period.[6] The original pyramidal structure, the Anu Ziggurat, dates to around 4000 B.C.E., and the White Temple was built on top of it circa 3500 B.C.E.[7] According to some historians, the design of the ziggurat was probably a precursor to that of the pyramids in Egypt, the earliest of which dates to c. 2600 B.C.E.: "The stepped design of the Pyramid of Zoser at Saqqara, the oldest known pyramid along the Nile, suggests that it was borrowed from the Mesopotamian ziggurat concept."[8] Others suggest that the earliest Egyptian pyramids in Saqqara may have been derived locally from the bench-shaped mastaba tomb.[9] "The earliest pyramid was the step pyramid of Djoser (2668-2649 B.C.E.) at Saqqara, and was an evolution of the traditional mastaba tomb, a bench-shaped superstructure."[10]

Africa

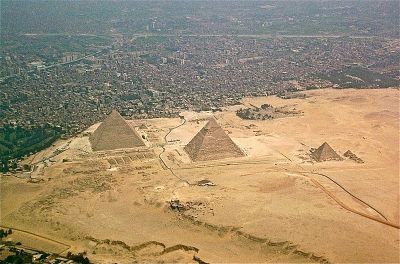

Egypt

The most famous pyramids are the Egyptian ones — huge structures built of bricks or stones, some of which are among the world's largest constructions. The Great Pyramid of Giza is the largest in Egypt and one of the largest in the world. Its base covers an area of around 53,000 square meters (570,000 sq ft). At 146.6 meters (481 ft) it was the tallest structure in the world until the Lincoln Cathedral was finished in 1311 C.E.

Ancient Egyptian pyramids were, in most cases, placed west of the river Nile because the divine pharaoh's soul was meant to join with the sun during its descent before continuing with the sun in its eternal round.[11] Over 100 pyramids have been discovered in Egypt,[12] most located near modern day Cairo.[13]

Most Egyptian pyramids had a smoothed white limestone surface. The primary building materials were granites, sandstones, and various types of limestones. The blocks of limestone have been found to contain fossil shells and nummulites, large lenticular fossils characterized by numerous coils.[14] The capstone was usually made of limestone, granite, or basalt, and some of them were plated with gold, silver, or electrum (an alloy of gold and silver) which is highly reflective in the bright sun.[11]

The ancient Egyptians built pyramids from 2700 B.C.E. until around 1700 B.C.E. The first pyramid was erected during the Third Dynasty by the Pharaoh Djoser and his architect Imhotep. This step pyramid consisted of six stacked mastabas.[12][15] Early kings such as Snefru built several pyramids, with subsequent kings adding to the number of pyramids until the end of the Middle Kingdom. The age of the pyramids reached its zenith at Giza in 2575–2150 B.C.E.

The last king to build royal pyramids was Ahmose I,[13] with later kings hiding their tombs in the hills, such as those in the Valley of the Kings in Luxor's West Bank. In Medinat Habu and Deir el-Medina, smaller pyramids were built by individuals. Smaller pyramids with steeper sides were also built by the Nubians who ruled Egypt in the Late Period.[16]

Sudan

While pyramids are commonly associated with Egypt, the nation of Sudan has 220 extant pyramids, the most numerous in the world.[17] The area of the Nile valley known as Nubia, which lies in present-day northern Sudan, was the site of three Kushite kingdoms during antiquity. Nubian pyramids were constructed at three sites to serve as tombs for the kings and queens of Napata and Meroë.

These pyramids have different characteristics than the pyramids of Egypt. The physical proportions of Nubian pyramids differ markedly from the Egyptian pyramids, being constructed at a steeper angle than the Egyptian ones. The Nubian pyramids are built of stepped courses of horizontally positioned stone blocks and range approximately 6–30 meters (20–98 ft) in height, but rise from fairly small foundation footprints, resulting in tall, narrow structures inclined at approximately 70°. Most also have offering temple structures abutting their base with unique Kushite characteristics. By comparison, Egyptian pyramids of similar height generally had foundation footprints that were at least five times larger and were inclined at angles between 40–50°.

Sahel

The Tomb of Askia, in Gao, Mali, is believed to be the burial place of Askia Mohammad I, one of the Songhai Empire's most prolific emperors. It was built at the end of the fifteenth century and is designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The tomb as a fine example of the monumental mud-building traditions of the West African Sahel. The complex includes the pyramidal tomb, two mosques, a cemetery, and an assembly ground. At 17 meters (56 ft) in height it is the largest pre-colonial architectural monument in Gao.[18] It is a notable example of the Sudano-Sahelian architectural style that later spread throughout the region.

Other pyramidal constructions of the Songhai Empire are the minaret of the Djinguereber Mosque of Timbuktu, the minaret of the Sankore university of Timbuktu, and the three tower-minarets of the Mosque of Djenne.

Nigeria

One of the unique structures of Igbo culture was the Nsude pyramids, at the Nigerian town of Nsude, northern Igboland. Ten pyramidal structures were built of clay/mud. The first base section was 60 ft (18 m) in circumference and 3 ft (0.9 m) in height. The next stack was 45 ft (14 m) in circumference. Circular stacks continued, till it reached the top. The structures were temples for the god Ala, who was believed to reside at the top. The structures were laid in groups of five parallel to each other. Because it was built of clay/mud like the Deffufa of Nubia, time has taken its toll requiring periodic reconstruction.[19]

Europe

Greece

Pausanias (second century C.E.) mentions two buildings resembling pyramids, one, 19 kilometers (12 mi) southwest of the still standing structure at Hellenikon,[20] a common tomb for soldiers who died in a legendary struggle for the throne of Argos and another which he was told was the tomb of Argives killed in a battle around 669/8 B.C.E. Neither of these still survive and there is no evidence that they resembled Egyptian pyramids.

There are also at least two surviving pyramid-like structures still available to study, one at Hellenikon and the other at Ligourio/Ligurio, a village near the ancient theatre Epidaurus. These buildings were not constructed in the same manner as the pyramids in Egypt. They do have inwardly sloping walls but other than those there is no obvious resemblance to Egyptian pyramids. They had large central rooms (unlike Egyptian pyramids) and the Hellenikon structure is rectangular rather than square, 12.5 by 14 meters (41 ft × 46 ft), which means that the sides could not have met at a point.[20]

The dating of these structures has been made from the pot shards excavated from the floor and on the grounds. The latest dates available from scientific dating have been estimated around the fifth and fourth centuries. Normally this technique is used for dating pottery, but here researchers have used it to try to date stone flakes from the walls of the structures. This has created some debate about whether or not these structures are actually older than Egypt.[20]

Roman Empire

The 27-metre-high Pyramid of Cestius was built by the end of the first century B.C.E. and still exists today, close to the Porta San Paolo. The pyramid was built as a tomb for Gaius Cestius, a magistrate and member of one of the four great religious corporations in Rome, the Septemviri Epulonum. It is of brick-faced concrete covered with slabs of white marble standing on a travertine foundation. The pyramid measures 100 Roman feet (29.6 m) square at the base and stands 125 Roman feet (37 m) high.[21]

There was another pyramid in Rome, named Meta Romuli ("Pyramid of Romulus"), standing in the Ager Vaticanus (today's Borgo). During the Middle Ages, the Pyramid of Cestius was known as the "Pyramid of Remus," and it was believed that these two pyramids were the tombs of the twins Romulus and Remus, the legendary founders of Rome. The larger "Pyramid of Romulus" was dismantled during the sixteenth century for its marble that was used in the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica.[22]

Spain

The Pyramids of Güímar refer to six rectangular pyramid-shaped, terraced structures, built from lava stone without the use of mortar. They are located in the district of Chacona, part of the town of Güímar on the island of Tenerife in the Canary Islands. The structures have been dated to the nineteenth century and their original function explained as a byproduct of contemporary agricultural techniques.

Other pyramids employing the same methods and materials of construction can be found in various sites on Tenerife. In Güímar itself there were nine pyramids, only six of which survive.

Americas

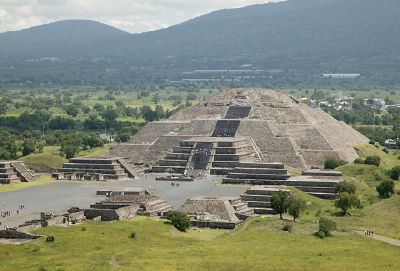

Mesoamerica

A number of Mesoamerican cultures also built pyramid-shaped structures. Mesoamerican pyramids were usually stepped, with temples on top, more similar to the Mesopotamian ziggurat than the Egyptian pyramid.

Chichen Itza is a large pre-Columbian archaeological site built by the Maya civilization located in the northern center of the Yucatán Peninsula, present-day Mexico. A dominant feature of the site is the Temple of Kukulcan (the Maya name for Quetzalcoatl), often referred to as "El Castillo" (the castle). This step pyramid has a ground plan of square terraces with stairways up each of the four sides to the temple on top.

The largest pyramid by volume is the Great Pyramid of Cholula, in the Mexican state of Puebla. Constructed in four stages beginning in the third century B.C.E. to completion in the ninth century C.E., it was dedicated to the deity Quetzalcoatl. This pyramid is considered the largest monument ever constructed anywhere in the world, and is still being excavated. The third largest pyramid in the world, the Pyramid of the Sun, at Teotihuacan is also located in Mexico. There is an unusual pyramid with a circular plan at the site of Cuicuilco, now inside Mexico City and mostly covered with lava from an eruption of the Xitle Volcano in the first century B.C.E. There are several circular stepped pyramids called Guachimontones in Teuchitlán, Jalisco as well.

Pyramids in Mexico were often used as places of human sacrifice. The Aztecs were noted for practicing human sacrifice on a large scale. Believing that the sun god Huitzilopochtli lost a daily battle each night, human sacrifices were offered to restore him to life and to prevent the end of the world that could happen on each cycle of 52 years. In the 1487 re-consecration of the Templo Mayor atop the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan, the number of human sacrifices is estimated at between 10,000 and 80,000 prisoners.[23]

Peru

Andean cultures used pyramids in various architectural structures such as the ones in Caral,the largest recorded site in the Andean region, with dates older than 2000 B.C.E. It was a thriving metropolis at roughly the same time as the great pyramids were being built in Egypt, and appears to be the model for the urban design adopted by Andean civilizations. The city of Caral was split into two sections, an "Upper Half" and a "Lower Half." These halves were divided naturally by the Supe River Valley. In the Upper Half there are six monumental complexes, each of which includes a pyramid, open plaza, and assemblage of residential buildings. In the Lower Half there are residential buildings, small pyramids, and one monumental complex called the "Temple of the Amphitheater."[24]

United States

Many pre-Columbian Native American societies of ancient North America built large pyramidal earth structures known as platform mounds. Such mounds were usually square, rectangular, or occasionally circular. Structures (domestic houses, temples, burial buildings, or other) were usually constructed atop such mounds.

Among the largest and best-known of these structures is Monks Mound at the site of Cahokia in what became Illinois, completed around 1100 C.E., which has a base larger than that of the Great Pyramid at Giza. Many of the mounds underwent repeated episodes of mound construction at periodic intervals, some becoming quite large. They are believed to have played a central role in the mound-building peoples' religious life and documented uses include semi-public chief's house platforms, public temple platforms, mortuary platforms, charnel house platforms, earth lodge/town house platforms, residence platforms, square ground and rotunda platforms, and dance platforms.[25] Cultures who built substructure mounds include the Troyville culture, Coles Creek culture, Plaquemine culture, and Mississippian cultures.

Asia

Central, East, and Southeast Asia

In east Asia, Buddhist stupas had been usually represented as tall pagodas. However, some pyramidal stupas remain in limited areas. There is a theory that these pyramid were inspired by Borobudur monument through Sumatran and Javanese monks.[26] Also, there is similar Buddhist monument in Vrang, Tajikistan.[27] There are at least nine Buddhist step pyramids in the world, four from former Gyeongsang Province of Korea, three from Japan, one from Indonesia (Borobudur) and one from Tajikistan.

China

There are many square flat-topped mound tombs in China. Most of these Chinese pyramids are ancient mausoleums and burial mounds built to house the remains of several early emperors of China and their imperial relatives. About 38 of them are located around 25 kilometers (16 mi) – 35 kilometers (22 mi) north-west of Xi'an, on the Guanzhong Plains in Shaanxi Province. The most famous is the Mausoleum of the First Emperor Qin Shi Huang (c. 221 B.C.E., who unified the seven pre-Imperial Kingdoms), located northeast of Xi'an and 1.7 km west of where the Terracotta Army was found.[28]

In the following centuries about a dozen more Han Dynasty royals were also buried under flat-topped pyramidal earthworks.

India

Numerous giant, granite, temple pyramids were made in South India during the Chola Empire, many of which are still in religious use today. Examples of such pyramid temples include Brihadisvara Temple at Thanjavur built by Raja Raja Chola in the eleventh century, the Brihadisvara Temple at Gangaikonda Cholapuram, and the Airavatesvara Temple at Darasuram. However, the temple pyramid that has the largest area is the Ranganathaswamy Temple in Srirangam, Tamil Nadu.

The Brihadisvara Temple was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1987; the Temple of Gangaikondacholapuram and the Airavatesvara Temple at Darasuram were added as extensions to the site in 2004.[29]

Ranganathaswamy Temple gopurams at Srirangam dedicated to Ranganatha, a reclining form of the Hindu deity Maha Vishnu.

Indonesia

Austronesian megalithic culture in Indonesia also featured earth and stone step pyramid structures called punden berundak as discovered in Pangguyangan site near Cisolok and in Cipari near Kuningan. The construction of stone pyramids is based on the native beliefs that mountains and high places are the abode for the spirit of the ancestors.[30]

The step pyramid is the basic design of eighth century Borobudur Buddhist monument in Central Java. However the later temples built in Java were influenced by Indian Hindu architecture, as displayed by the towering spires of Prambanan temple. In the fifteenth century Java during late Majapahit period saw the revival of Austronesian indigenous elements as displayed by Sukuh temple that somewhat resemble Mesoamerican pyramid, and also stepped pyramids of Mount Penanggungan.

Modern examples

Modern pyramid mausoleums

With the Egyptian Revival movement in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, pyramids were becoming more common in funerary architecture. Two pyramid-shaped tombs were erected in Maudlin's Cemetery, Ireland, c. 1840; they are believed to belong to the local De Burgh family. The tomb of Quintino Sella, outside the monumental cemetery of Oropa, is pyramid-shaped.[31]

This style was especially popular with tycoons in the US. Hunt's Tomb in Phoenix, Arizona and Schoenhofen Pyramid Mausoleum in Chicago are some of the notable examples. Even today some people build pyramid tombs for themselves. Nicolas Cage, for example, bought a pyramid tomb for himself in a famed New Orleans graveyard.[32]

Other modern pyramids

- The Louvre Pyramid in Paris, France, in the court of the Louvre Museum, is a 20.6 meters (about 70 feet) glass structure which acts as an entrance to the museum. It was designed by the American architect I. M. Pei and was completed in 1989. The Pyramide Inversée (Inverted Pyramid) is displayed in the underground Louvre shopping mall.

- The Luxor Hotel in Las Vegas, United States, is a 30-story true pyramid with light beaming from the top.

- The 32-story Memphis Pyramid in Memphis, Tennessee (a city named after the ancient Egyptian capital whose name itself was derived from the name of one of its pyramids). Built in 1991, it was the home court for the University of Memphis men's basketball program, and the National Basketball Association's Memphis Grizzlies until 2004. It was not regularly used as a sports or entertainment venue after 2007, and in 2015 it was re-purposed as a Bass Pro Shops megastore.

- The Walter Pyramid, home of the basketball and volleyball teams of the California State University, Long Beach, campus in California, United States, is an 18-story-tall blue true pyramid.

- The 48-story Transamerica Pyramid in San Francisco, California, designed by William Pereira, one of the city's symbols.

- The 105-story Ryugyong Hotel in Pyongyang, North Korea.

- A former museum/monument in Tirana, Albania is commonly known as the "Pyramid of Tirana". It differs from typical pyramids in having a radial rather than square or rectangular shape, and gently sloped sides that make it short in comparison to the size of its base.

- The Slovak Radio Building in Bratislava, Slovakia is shaped like an inverted pyramid.

- The Palace of Peace and Reconciliation in Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan.

- The three pyramids of Moody Gardens in Galveston, Texas.

- The Co-Op Bank Pyramid or Stockport Pyramid in Stockport, England is a large pyramid-shaped office block in Stockport in England. (The surrounding part of the valley of the upper Mersey has sometimes been called the "Kings Valley" after the Valley of the Kings in Egypt.)

- The Ames Monument in southeastern Wyoming honoring the brothers who financed the Union Pacific Railroad.

- The Ballandean Pyramid, at Ballandean in rural Queensland is a 15-metre folly pyramid made from blocks of local granite.

- The Karlsruhe Pyramid is a pyramid made of red sandstone, located in the centre of the market square of Karlsruhe, Germany. It was erected in the years 1823–1825 over the vault of the city's founder, Margrave Charles III William (1679–1738).

- The Muttart Conservatory greenhouses in Edmonton, Alberta.

- Hanoi Museum with an overall design of a reversed Pyramid.

- The Pyramid culture-entertainment complex and Monument of the Kazan siege in Kazan, Russia.

- The Donkin Memorial, erected on a Xhosa reserve in 1820 by Cape Governor Sir Rufane Shaw Donkin in memory of his late wife Elizabeth, in Port Elizabeth, South Africa. The pyramid is used in many different coats-of-arms associated with Port Elizabeth. Adjacent to the Pyramid is the lighthouse (1863) that houses the Nelson Mandela Bay Tourism office, as well as a 12 x 8 m South African Flag flying from a 65 m high flagpole. It also forms part of the Route 67 Public Art route.

Slovak Radio Building, Bratislava, Slovakia.

Notes

- ↑ Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott,πυραμίς A Greek-English Lexicon (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1940). Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ↑ Robert Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek (Brill, 2010, ISBN 978-9004174184).

- ↑ G. Patrick Flanagan, Pyramid Power: The Science of the Cosmos (PhiSciences, 2016 (original 1975), ISBN 978-0692643419).

- ↑ Max Toth and Greg Nielsen, Pyramid Power (New York: Warner Destiny, 1985, ISBN 978-0892811069).

- ↑ Andrew Neher, Paranormal and Transcendental Experience: A Psychological Examination (Dover Publications, 2011, ISBN 0486261670).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Harriet Crawford, Sumer and the Sumerians (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991, ISBN 0521388503).

- ↑ Nicola Crusemann, Margarete van Ess, Markus Hilgert, Beate Salje, and Timothy Potts (eds.), Uruk: First City of the Ancient World (J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019, ISBN 978-1606064443).

- ↑ Colbert C. Held and John Thomas Cummings, Middle East Patterns: Places, People, and Politics (Routledge, 2015, ISBN 978-0813350202).

- ↑ Craig B. Smith, How the Great Pyramid Was Built (Smithsonian, 2018, ISBN 978-1588346223).

- ↑ Charlotte Booth, How to Survive in Ancient Egypt (Pen and Sword History, 2020, ISBN 978-1526753496).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Marissa McCauley, How were the Egyptian pyramids built? Science Daily (March 29, 2008; updated April 15, 2014). Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Mark Lehner, The Complete Pyramids: Solving the Ancient Mysteries (Thames & Hudson, 2008, ISBN 0500285470).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Joyce Filer, Pyramids (Oxford University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0195305210).

- ↑ Jennifer Viegas, Pyramids packed with fossil shells ABC Science (April 28, 2008). Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- ↑ Joseph Davidovits, They Built the Pyramids (Geopolymer Institute, 2008, ISBN 978-2951482029).

- ↑ James Harpur, Pyramid (Barnes & Noble Books, 1997, ISBN 978-0760702154).

- ↑ Lawrence Pollard, Sudan's past uncovered BBC (September 9, 2004). Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ↑ Tomb of Askia UNESCO World Heritage Convention. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- ↑ George Thomas Basden, Among the Ibos of Nigeria (Legare Street Press, 2022 (original 1921), ISBN 978-1015420113).

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Garrett G. Fagan, (ed.), Archaeological Fantasies: How Pseudoarchaeology Misrepresents the Past and Misleads the Public (Routledge, 2006, ISBN 978-0415305938).

- ↑ Amanda Claridge, Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide (Oxford University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0199546831).

- ↑ Peter Lacovara, Pyramids and Obelisks Beyond Egypt Aegyptiaca 2 (2018): 124–129. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ↑ Michael Harner, The Enigma of Aztec Sacrifice Natural History 86(4) (April 1977): 46-51. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ↑ William H. Isbell and Helaine Silverman (eds.), Andean Archaeology III: North and South (Springer, 2006, ISBN 978-0387289397).

- ↑ Raymond D. Fogelson (ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Southeast (Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0874741940).

- ↑ 古代における塔型建築物の伝播 ボロブドゥールと奈良頭塔の関係について Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ↑ Paul Salopek, The Ruby Sellers of Vrang National Geographic Magazine (October 2, 2017). Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ↑ Maurice Cotterell, The Terracotta Warriors: The Secret Codes of the Emperor's Army (Bear & Company, 2004, ISBN 978-1591430339).

- ↑ Great Living Chola Temples UNESCO World Heritage Convention. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ↑ Timbul Haryono, Sendratari mahakarya Borobudur (Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia, 2011, ISBN 978-9799103338).

- ↑ The Monumental Cemetery Santuario di Oropa. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ↑ Nicolas Cage's Pyramid Tomb Atlas Obscura. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Basden, George Thomas. Among the Ibos of Nigeria. Legare Street Press, 2022 (original 1921). ISBN 978-1015420113

- Beekes, Robert. Etymological Dictionary of Greek. Brill, 2010. ISBN 978-9004174184

- Booth, Charlotte. How to Survive in Ancient Egypt. Pen and Sword History, 2020. ISBN 978-1526753496

- Claridge, Amanda. Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. Oxford University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0199546831

- Cotterell, Maurice. The Terracotta Warriors: The Secret Codes of the Emperor's Army. Bear & Company, 2004. ISBN 978-1591430339

- Crawford, Harriet. Sumer and the Sumerians. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 0521388503

- Crusemann, Nicola, Margarete van Ess, Markus Hilgert, Beate Salje, and Timothy Potts (eds.), Uruk: First City of the Ancient World. J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019. ISBN 978-1606064443

- Davidovits, Joseph. They Built the Pyramids. Geopolymer Institute, 2008. ISBN 978-2951482029

- Fagan, Garrett G. (ed.). Archaeological Fantasies: How Pseudoarchaeology Misrepresents the Past and Misleads the Public. Routledge, 2006. ISBN 978-0415305938

- Filer, Joyce. Pyramids. Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0195305210

- Flanagan, G. Patrick. Pyramid Power: The Science of the Cosmos. PhiSciences, 2016 (original 1975). ISBN 978-0692643419

- Fogelson,Raymond D. (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians: Southeast. Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0874741940

- Harpur, James. Pyramid. Barnes & Noble Books, 1997. ISBN 978-0760702154

- Haryono, Timbul. Sendratari mahakarya Borobudur. Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia, 2011. ISBN 978-9799103338

- Held, Colbert C., and John Thomas Cummings. Middle East Patterns: Places, People, and Politics. Routledge, 2015. ISBN 978-0813350202

- Isbell, William H., and Helaine Silverman (eds.). Andean Archaeology III: North and South. Springer, 2006. ISBN 978-0387289397

- Lehner, Mark. The Complete Pyramids: Solving the Ancient Mysteries. Thames & Hudson, 2008. ISBN 0500285470

- Smith, Craig B. How the Great Pyramid Was Built. Smithsonian, 2018. ISBN 978-1588346223

- Toth, Max, and Greg Nielsen. Pyramid Power. New York: Warner Destiny, 1985. ISBN 978-0892811069

External links

All links retrieved November 9, 2023

- The Egyptian Pyramid Smithsonian

- Pyramids at Giza National Geographic

- Pyramid World History Encyclopedia

- Ancient Pyramids Around the World Smithsonian Magazine

- 15 Must-Visit Pyramids Around the World History Hit

- 10 Ancient Pyramids around the World Heritage Daily

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

.jpg/400px-Koh_Ker_temple(2007).jpg)

_(37254366620).jpg/120px-Sri_Ranganathaswamy_Temple%2C_dedicated_to_Vishnu%2C_in_Srirangam%2C_near_Tiruchirappali_(24)_(37254366620).jpg)