Hermann Rorschach (November 8, 1884 - April 2, 1922), nicknamed Klecks, was a Swiss Freudian psychiatrist, best known for developing the projective test known, from his name, as the Rorschach inkblot test. The test is based on the theory that responding to ambiguous or unstructured stimuli would elicit disclosure of innermost feelings. Rorschach created ten standardized cards as well as a scoring system for the Inkblot test. Since his death, Rorschach's work has won international respect.

The Inkblot test has generated more published research than any other personality measure with the exception of the MMPI. However, it has not been without controversy as many have argued that the very nature of this projective test, in which one's emotional and psychological state is projected into the image to produce meaning, is inherently unreliable. Rorschach himself recognized that it was a work in progress, and it was his untimely death that prevented him from its further development and refinement.

Despite its imperfections, Rorschach's work has been a valuable contribution as both a diagnostic test for those suffering, or potentially suffering, psychological instability or disorder, and as a way of trying to understand the depth of human personality and thus to establish a world in which all people can achieve happiness and fulfill their potential.

Life

Hermann Rorschach was born on November 8, 1884, in Zurich, Switzerland. Foreshadowing his future, he was nicknamed Klecks, meaning “inkblot,” because of his interest in Klecksography during his teen years. Klecksography was a game played by Swiss children and consisted of placing an ink blot on paper and folding it to obtain the form of a butterfly or a bird.

He was known as a studious and orderly student who received excellent grades in all disciplines. He considered pursuing his father's career as an artist, but instead chose a different path—psychiatry.

Rorschach attended several universities before receiving his M.D. from the University of Zurich in 1909, then worked in Russia for a year before returning to Switzerland to practice. Rorschach studied psychiatry at Burghölzli university clinic in Zurich with teachers like Auguste-Henri Forel (1848-1931), the almost equally famous successor, Eugen Bleuler 1857-1939), and Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961), who had just researched and developed the association test to explore the unconscious mind. During this time period, the work of Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) was also just beginning to gain in popularity.

At the time of his graduation, Rorschach became engaged to a Russian girl named Olga Stempelin, whom he married the following year. They moved to Russia, but he returned to Switzerland within the year, despite the fact that his wife could not join him until a year later due to the war. She noted "in spite of his interest in Russia and the history of the Russians, he remained a true Swiss, attached to his native land." The couple had two children, a son born in 1917, and a daughter born in 1919.

Rorschach was known as having an appealing personality, and had a reputation as a brilliant and profound conversationalist. Although somewhat reserved, he was a man of great kindness and generosity to those closest to him. There is not a great deal written about Rorschach's life, but a compilation of his personal correspondence sheds some light. In a letter to his sister Anna in 1906, he expressed "Healing the human soul is the chief good a man can do," revealing his deep concern for the individual's suffering.

Unfortunately, Rorschach died in 1922, at the young age of 38, due to complications from appendicitis in Herisau, Switzerland, where he served as an Assistant Director at the regional psychiatric hospital. In Eugen Bleuler´s words "the hope for a whole generation of Swiss psychiatry" died on April 2, 1922.

Work

Rorschach's first position was in the psychiatric hospital in Münsterlingen under the supervision of Eugen Bleuler. Rorschach was deeply interested in psychoanalysis and during the 1910s, he began publishing psychoanalytic articles. One publication praised the therapeutic value of artistic activity; he saw his patients’ art productions as an expression of the anomalies of personality.

In 1911, Rorschach began experimenting with ink blot interpretation and Carl Jung's word association test. He was not the first in this work, which had such famous forerunners as Alfred Binet and Justinus Kerner.

Rorschach was elected vice president of the Swiss Psychoanalytic Society in 1919. Several of Rorschach's colleagues, including his supervisor, Eugen Bleuler, were very positive to Rorschach's work and encouraged him to publish his findings. In 1921, Rorschach published the results of his studies on 300 mental patients and 100 normal subjects in the monograph, Psychodiagnostik. Unfortunately, Rorschach died prematurely in 1922, before he could properly test and evaluate his invention, and before it reached popularity in the 1940s.

The inkblot test

Rorschach had begun research on the use of ink blots in determining personality traits as early as 1911, and Rorschach was aware of the work of other researchers. However, he found that they had not developed a consistent method of administering and scoring such a test. Rorschach tested both emotionally healthy people and patients in the mental hospital where he was employed, devising a system for testing and analyzing the results.

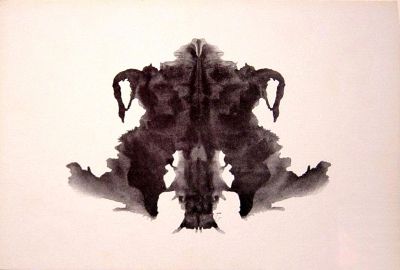

Rorschach devised the ten standardized cards used today as well as a scoring system for the Inkblot test. There are ten official inkblots. Five inkblots are black ink on white. Two are black and red ink on white. Three are multicolored. The tester shows the inkblots in a particular order and asks the patient, for each card, "What might this be?" After the patient has seen and responded to all the inkblots, the psychologist then gives them to him again one at a time to study. The patient is asked to list everything he sees in each blot, where he sees it, and what there is in the blot that makes it look like that. The blot can also be rotated. As the patient is examining the inkblots, the psychologist writes down everything the patient says or does, no matter how trivial.

Rorschach considered his test to be a test of "perception and apperception," rather than imagination. The original scoring system emphasizes perceptual factors—for example, whether a response is influenced by form, perceived movement, or color of the blot.

He presented his system in his publication, Psychodiagnostik (1921), explaining not only the test itself but also his theory of human personality. He suggested that as each person displays a mixture of traits, some guided by internal factors and others by external factors; the ink-blot test would reveal the amount of each trait and their strengths and weaknesses.

Despite lack of sales of his publication, to the extent that the publisher, Bircher, went bankrupt, those who did respond were extremely critical. Undeterred, Rorschach spoke of his plans to improve upon the system, looking upon his Psychodiagnostik as only a preliminary work that he intended to develop further. Unfortunately, his death prevented that.

Controversy

Despite initial rejection, the Rorschach inkblot test has become extremely popular, and well used. However it has also proved controversial.

As a projective test, it has been argued that the results are not properly verifiable. The Exner system of scoring, which interprets the test in terms of what factor (shading, color, outline, and so forth) of the inkblot leads to each of the tested person's comments, is meant to address this, but problems of test validity remain. However, there is substantial research indicating the utility of the measure for detecting such conditions as thought disorders, mood and anxiety disorder, personality disorders, and psychopath.

Supporters of the test try to keep the actual cards secret so that the answers are spontaneous. This practice is consistent with the American Psychological Association's ethical standards of preserving test security. The official test is sold only to licensed professionals. These ethics were violated in 2004, when the method of administering the tests and the ten official images were published on the Internet. This reduced the value of projective testing for those individuals who have become familiar with the material, potentially impacting their care in a negative fashion. The Rorschach Society claims the blots are copyrighted. However, this has been disputed.

Legacy

After Rorschach's death, Hans Huber founded his own publishing house and he purchased Psychodiagnostics from the inventory of Ernst Bircher. Since 1927, Hans Huber has been the publisher of Psychodiagnostik, taking great pains to maintain the identical reproduction of the original inkblots.

Rorschach's original scoring system was developed further by, amongst others, Bruno Klopfer. John E. Exner summarized some of these later developments in the comprehensive Exner system, at the same time trying to make the scoring more statistically rigorous. Most systems are based on the psychoanalytic concept of object relations.

The Exner system is very popular in the U.S., while in Europe the textbook by Evald Bohm, which is closer to the original Rorschach system as well as more inspired by psychoanalysis is often considered to be the standard reference work.

Although controversy continues regarding the validity of the Inkblot test results, Rorschach's correspondence indicates his life's work Psychodiagnostics should not be considered as directions for a new method in psychological testing only. His intention was to view the nature of personalty as an interpersonal reality that emerges from the participant's responses. In fact, Rorschach thought in interpersonal terms, long before the "object-relation" and "object-representation" theories had evolved. Rorschach's personal letters revealed that he was well aware of the limits of his method, and cautioned:

It is to be understood that the test is primarily an aid to clinical diagnosis. To be able to draw conclusions from the scoring of so large a number of factors (as must be considered in making a valid diagnosis) requires a great deal of practice in psychological reasoning and a great deal of practice with the test.

The letters further reveal that he believed the experiment itself was not nearly exhausted and he further disclosed, "obviously even now there are important factors hidden in the protocols…they have still have to be found.” This letter, written in 1921, just before his sudden and untimely death, reveal that Rorschach was sure that his method could be further developed. It is quite possible that much of the ensuing controversy has resulted from misunderstanding an immense project that was not yet completed by the inventor.

In the years since his death, Rorschach's work has won international respect and an institute was founded in his name in New York in 1939. The Rorschach Inkblot Method (RIM) has generated more published research than any other personality measure, with the exception of the MMPI. The Rorschach is also the second most commonly used test in forensic assessment, again, after the MMPI.

Publications

- 1924. Rorschach, Hermann. Manual for Rorschach Ink-blot Test. Chicago, IL: Stoelting.

- 1924. Rorschach, Hermann and Emil Oberholzer. The Application of the Interpretation of Form to Psychoanalysis. Chicago.

- 1932. Rorschach, Hermann and S.J. Beck. The Rorschach Test as Applied to a Feeble-minded Group. New York.

- 1938. Rorschach, Hermann and Bruno, Klopfer. Rorschach Research Exchange. New York.

- [1942] 2011. Rorschach, Hermann. Psychodiagnostics; A Diagnostic Test Based on Perception. Includes Rorchach's paper "The Application of the Form interpretation Test" (published posthumously by Emil Oberholzer). Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1245159463

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dawes, Robyn M. 1991. "Giving up Cherished Ideas: The Rorschach Ink Blot Test," IPT Journal 3. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- Ellenberger, H. 1954. "The Life and Work of Hermann Rorschach (1884-1922)" In Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 18:172-219.

- Exner, John E. 2002. The Rorschach, Basic Foundations and Principles of Interpretation Volume 1. Wiley. ISBN 0471386723

- Pichot, Pierre. 1984. "Centenary of the Birth of Hermann Rorschach." Journal of Personality Assessment 48(6):591.

- Rehm, Helga Charlotte. 2005. "Hermann Rorschach's Correspondence." Journal of Personality Assessment 85(1):98-99.

- Weiner, Irving B. 2001. "The Value of Rorschach Assessment" In Harvard Mental Health Letter 18(6):4.

- Wood, James M., M. Teresa Nezworski, Scott O. Lilienfeld, and Howard N. Garb. 2003. What's Wrong with the Rorschach? Science Confronts the Controversial Inkblot Test. Jossey-Bass. ISBN 078796056X

External links

All links retrieved December 21, 2023.

- Hermann Rorschach Whonamedit?

- International Society of the Rorschach and Projective Methods

- The Classical Rorschach

- Rorschach inkblot test The Skeptic's Dictionary

- Unofficial Rorschach website

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.