Sir John Macdonald

| The Right Honourable Sir John Alexander Macdonald | |

| |

1st Prime Minister of Canada

| |

| In office July 1, 1867 – November 5, 1873 October 17, 1878 – June 6, 1891 | |

| Preceded by | (none) Alexander Mackenzie |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | Alexander Mackenzie John Abbott |

| Born | January 11 1815 Glasgow, Scotland |

| Died | June 6 1891 (aged 76) Ottawa, Ontario |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Religion | Presbyterian, converting later to Anglican |

Sir John Alexander Macdonald, GCB, KCMG, PC, QC, DCL, LL.D (January 11, 1815 – June 6, 1891), was the first Prime Minister of Canada. He was one of the architects of Confederation in 1867, which created the Dominion of Canada, the first settler colony to be granted independence by the United Kingdom. His championship of the cross-continental railroad did much to unify the new nation. Macdonald's tenure in office spanned 19 years, making him the second longest serving Prime Minister of Canada. He is the only Canadian Prime Minister to win six majority governments and won praise for having helped forge a nation of sprawling geographic size, with two diverse European colonial origins, and a multiplicity of cultural backgrounds and political views. He did face allegations of financial corruption, and in later life drank heavily. However, what became the nation-state of Canada owes much to his visionary leadership and to the impetus he gave to the forming of a sense of Canadian identity while still respecting regional or provincial identities.

Personal life

Macdonald was born in Glasgow, Scotland. His father was Hugh Macdonald, an unsuccessful merchant, who met his mother, Helen Shaw, in 1811. After the failure of his father's business ventures, his family emigrated to Kingston, Upper Canada, in 1820. along with thousands of others seeking affordable land and promises of new prosperity. In Kingston, Hugh Macdonald's business ventures were more successful than they had been in Scotland.[1] When John was 10, he was sent to Midland Grammar School, in Kingston, Ontario.

In 1843, at the age of 28, he married his half second cousin, Isabella Clark (1811-1857), (they had a maternal grandmother in common). Soon after the wedding, Isabella became terribly sick with a mysterious illness. She depended on medication and spent most of her time in bed. Macdonald moved to Bellevue House in Kingston with his family in 1848, in the hope that the fresh suburban air would help Isabella's condition. This experiment, however, was a failure. Moreover, his budding political and legal career prevented him from spending as much time with his wife as he felt he should, especially after she obtained treatment at a hospital in New Haven, CT. Isabella and John had two children, John Alexander, who died when he was 13 months old, and Hugh John, who was raised by Macdonald's sister Margaret and her husband, James Williamson, after Isabella's death in 1857. Hugh John went on to become premier of the Province of Manitoba.

In 1867, at the age of 52, Macdonald married his second wife, Susan Agnes Bernard (1836-1920). They had one daughter, Margaret Mary Theodora Macdonald (1869-1933), who was born with hydrocephalus and suffered from physical and mental disabilities. Macdonald always hoped she would recover, but she never did.

Law career

Macdonald began articling for George Mackenzie, a Kingston lawyer, in 1830, at the age of 15.[2] A promising law student, Macdonald was managing a branch office in Napanee at age 17.[3] From 1833 to 1835, Macdonald operated the law firm of his cousin, Lowther Pennington Macpherson, in Picton.[4] Macdonald then set up his own law practice in August 1835, in Kingston. Macdonald was then called to the Bar on February 6, 1836. Soon after opening his own law firm he took in two students: Oliver Mowat and Albert Campbell.[5] He earned the esteem of many by his unsuccessful but solid defense of the American raiders who were captured at the Battle of the Windmill (1838, near Prescott, Ontario) in the Rebellions of 1837.

Political rise

In 1843, Macdonald entered politics, standing for the office of Alderman in Kingston, a position to which he was elected.[6] He exhibited his first interest in politics. In 1844 he was elected to the legislature of the Province of Canada to represent Kingston,[7] gained the recognition of his peers and in 1847, was appointed Receiver General in William Henry Draper's administration. However, Macdonald had to give up his portfolio when Draper's government lost the next election. He left the Conservatives, hoping to build a more moderate and palatable base. In 1854, he helped to found the Liberal-Conservative Party under the leadership of Sir Allan McNab. Within a few years, the Liberal-Conservatives would attract all of the old Conservative base as well as some centrist Reformers. The Liberal-Conservatives came to power in 1854, and under the new administration Macdonald was appointed Attorney-General. During his time in cabinet, Macdonald was usually the most powerful minister, even when other men held the premiership.

Joint Premier

In the next election Macdonald continued his rise in politics by becoming Joint Premier of the Province of Canada with Sir Étienne-Paschal Taché of Canada East for the years 1856 and 1857.

Taché resigned in 1857, and George-Étienne Cartier took his place. In the election of 1858, the Macdonald-Cartier government was defeated and they resigned as Premiers. In an interesting piece of politics, the Governor General of Canada asked Cartier to become the senior Premier, only a week after his defeat. Cartier accepted and brought Macdonald into office along with him. This was legal as any member of the cabinet could re-enter the cabinet provided they did so within a month of resigning their previous position. Macdonald focused on communications and defence, especially the Intercolonial Railway. Canada had to pressure the Colonial Office, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and PEI to, as one historian notes, "consider an ambitious scheme proposed by their pushing and turbulent neighbour, Canada."[8]

The coalition government was again defeated in 1862. Macdonald then served as the leader of the opposition until the election of 1864, when Taché came out of retirement and joined ranks with Macdonald to form the governing party yet again.

Confederation

The Province of Canada was one of six British colonies. Conversation was in process exploring the possibility of uniting to form a confederation, partly for economic reasons but also partly to consolidate against what was perceived to be a threat from the larger state to the South, the United States. Macdonald was a strong supporter of confederation, which took place in July 1867, following the passing by the British Parliament of the North American Act. Initially, three of the six colonies joined what became the Dominion of Canada, the Province of Canada (itself a union of two former entities), New Brunswick and Novia Scotia. Later, the remaining three colonies and various other territories also joined. The last to do so was Newfoundland, in 1949. Macdonald saw Confederation as a legislative union similar to that between the constituent parts of the United Kingdom of Great Britain. Provinces would retain their distinctive identities, just as the Welsh, Scottish and English have their own identities. However, he was also interested in forging a sense of national belonging.

First Prime Minister of the Dominion of Canada

Queen Victoria knighted John A. Macdonald for playing an integral role in bringing about Confederation. His creation as a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George was announced at the birth of the Dominion, July 1, 1867. An election was held in August which put Macdonald and his Conservative party into power.

Macdonald's vision as Prime Minister was to enlarge the country and unify it. Accordingly, under his rule Canada bought Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory from the Hudson's Bay Company for £300,000 (about $11,500,000 in modern Canadian dollars). This land became the Northwest Territories. In 1870, Parliament passed the Manitoba Act, creating the province of Manitoba out of a portion of the Northwest Territories in response to the Red River Rebellion led by Louis Riel.

In 1871, Britain added British Columbia to Confederation, making it the sixth province. Macdonald promised a transcontinental railway connection to persuade the province to join, which his opponents decried as a highly unrealistic and expensive promise. However, he knew that for the nation to develop a sense of common identity and belonging, transportaion was vital. In 1873 Prince Edward Island joined Confederation, and Macdonald created the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (then called the "North-West Mounted Police") to act as a police force for the vast Northwest Territories.

After the Pacific scandal in 1873, in which Macdonald was accused of taking bribes to award contracts for the construction of the railway, he was forced to resign and Liberal leader Alexander Mackenzie formed a caretaker government. The subsequent 1874 federal election was won by the Mackenzie Liberals. Macdonald was returned to power in 1878, on the strength of the National Policy, a plan to promote trade within the country by protecting it from the industries of other nations and renewing the effort to complete the previously promised Canadian Pacific Railway, which was accomplished in 1885. That year, Louis Riel also returned to Canada and launched the North-West Rebellion in the territory of Saskatchewan, but now that there was a railway through the area the North-West Mounted Police were quickly sent to put it down. The trial and subsequent execution of Riel for treason caused a deep political division between French Canadians, who supported Riel (a culturally French Métis) and English Canadians, who supported Macdonald.

Last term in office

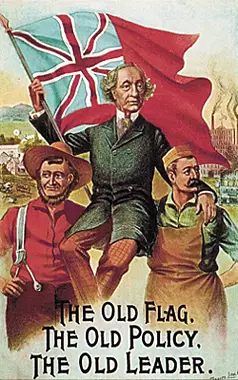

In 1891, Macdonald won the elections again. His campaign on this occasion focused on the "American threat," drawing on Canada's symbols and emerging sense of nationhood to promote a feeling of patriotism and loyalty to the nation. Critics suggest, however, that under Macdonald, it was middle-class British Canadians who gained most from his administration.[9]. However, this final term in office was short-lived. By this time, the 76-year-old political warhorse started to feel the years of overwork, stress, drink, and several bouts of severe illness, including a gallstone problem in 1870, that turned his office into a sick room for two months. On May 29, 1891, Sir John suffered a severe stroke, which robbed him of the ability to speak, and from which he would never recover. He died a week later on June 6, 1891, at the age of 76. He would lie in state in the Canadian Senate Chamber (Prime Ministers now lie in state in the Hall of Honour in the Centre Block) where grieving Canadians turned out in the thousands to pay their respects. His state funeral was held on June 9, attended by hundreds of thousands of people. He is buried in Cataraqui Cemetery near Kingston, Ontario. None of his children left heirs and he was survived by a relative, Hugh Gainsford.

Supreme Court appointments

Macdonald chose the following jurists to be appointed as justices of the Supreme Court of Canada by the Governor General:

- Christopher Salmon Patterson (October 27, 1888–July 24, 1893)

- John Wellington Gwynne (January 14, 1879–January 7, 1902)

- Sir William Johnstone Ritchie (as Chief Justice, January 11, 1879–September 25, 1892; appointed a Puisne Justice under Prime Minister Mackenzie, September 30, 1875)

Freemasonry

Macdonald was a Freemason, initiated in 1844 at St. John’s Lodge No. 5 in Kingston. In 1868, he was named by the United Grand Lodge of England as its Grand Representative near the Grand Lodge of Canada (in Ontario) and the rank of Past Grand Senior Warden conferred upon him. He continued to represent the Grand Lodge of England until his death in 1891. His commission, together with his apron and gauntlets, are in the Masonic Temple at Kingston, along with his regalia as Past Grand Senior Warden. Among the books in his library was a very rare copy of the first Masonic book published in Canada, A History of Freemasonry in Nova Scotia (1786).

Legacy

Macdonald is depicted on the Canadian ten-dollar bill. He also has bridges, airports, and highways named after him (such as the Macdonald-Cartier Freeway), as well as a plethora of schools across the country. Macdonald and his son, Hugh John Macdonald briefly sat together in the Canadian House of Commons prior to the elder Macdonald's death.

In 2004, Macdonald was nominated as one of the top ten "Greatest Canadians" by viewers of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. He is considered by some Canadian political scientists to be the founder of the Red Tory tradition. As the father of Confederation, he is also considered to be the architect of modern Canada. His brainchild, the transcontinental railway, helped to bind what had been a series of separate colonies, each with their own identity, into a nation state.

Notes

- ↑ Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Sir John A Macdonald. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ↑ Libraries and Archives Canada, The Right Honourable Sir John Alexander Macdonald. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ↑ The Canadian Encyclopedia, Macdonald, Sir John Alexander. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ↑ Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, MACDONALD, Sir JOHN ALEXANDER. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ↑ Kingston Historical Society, John A. Macdonald's Kingston.

- ↑ Canadian Confederation at Libraries and Archives, Canada, Sir John A. Macdonald. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ↑ The Quebec History Encyclopedia, Marianoplous College, Sir John A. Macdonald. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ↑ Donald Creighton, John A. Macdonald, Old Chieftain v 2 (Toronto: Macmillan, 1955), p. 273.

- ↑ Patricia K. Wood, "Defining 'Canadian': Anti-Americanism and Identity in Sir John A Macdonald's Nationalism," Journal of Canadian Studies, July 1, 2001.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Creighton, Donald. John A. Macdonald: The Young Politician. Toronto: Macmillan, 1952.

- Johnson, J. K and P.B. Waite. Macdonald, Sir John Alexander. In Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- Phenix, Patricia. Private Demons, The Tragic Personal Life of John A. Macdonald. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2006. ISBN 9780771070440

- Sletcher, Michael. "Sir John A. Macdonald." In James Eli Adams, and Tom and Sara Pendergast, eds., Encyclopedia of the Victorian Era. Danbury, CT: Grolier Academic Reference, 2004. ISBN 9780717258604

- Waite, P. B. Macdonald: His Life and World. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1975. ISBN 9780070823013

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2023.

- Biography at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

- John Macdonald's Gravesite

- Correspondence of Sir John Macdonald; selections from the correspondence of the Right Honorable Sir John Alexander Macdonald, first Prime Minister of the Dominion of Canada, made by his literary executor Sir Joseph Pope (1921)

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Sir Allan Napier MacNab |

Joint Premiers of the Province of Canada - Canada West 1856 – 1858 |

Succeeded by: George Brown |

| Preceded by: George Brown |

Joint Premiers of the Province of Canada - Canada West 1858 – 1867 |

Succeeded by: himself as Prime Minister of Canada and Sir John Sandfield Macdonald as Premier of Ontario |

| Preceded by: None |

Leader of the Conservative Party of Canada 1867 – 1891 |

Succeeded by: Sir John J.C. Abbott |

| Preceded by: None |

Prime Minister of Canada 1867 – 1873 |

Succeeded by: Alexander Mackenzie |

| Preceded by: none |

Minister of Justice and Attorney General 1867 – 1873 |

Succeeded by: Antoine Dorion |

| Preceded by: Alexander Mackenzie |

Leader of the Opposition 1873 – 1878 |

Succeeded by: Alexander Mackenzie |

| Preceded by: Alexander Mackenzie |

Prime Minister of Canada 1878 – 1891 |

Succeeded by: Sir John J.C. Abbott |

| Preceded by: David Mills |

Minister of the Interior 1878 – 1888 |

Succeeded by: Edgar Dewdney |

| Preceded by: John Henry Pope |

Minister of Railways and Canals 1889 – 1891 |

Succeeded by: Mackenzie Bowell (acting) |

| Parliament of Canada | ||

| Preceded by: none |

Member of Parliament for Kingston 1867 – 1878 |

Succeeded by: Alexander Gunn |

| Preceded by: Francis James Roscoe |

Member of Parliament for Victoria 1878 – 1882 |

Succeeded by: E.C. Baker |

| Preceded by: John Rochester |

Member of Parliament for Carleton 1882 – 1887 |

Succeeded by: George Dickinson |

| Preceded by: Alexander Gunn |

Member of Parliament for Kingston 1887 – 1891 |

Succeeded by: James H. Metcalfe |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.